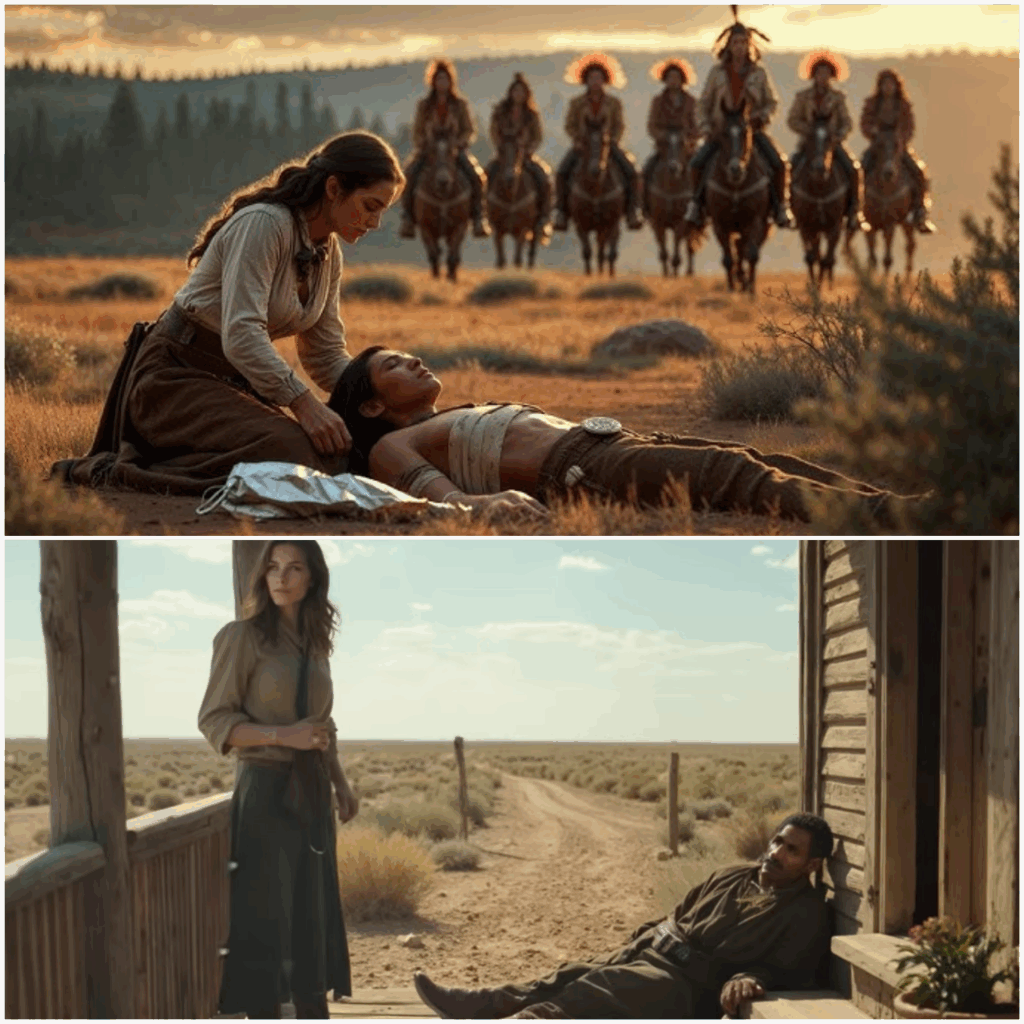

She Nursed a Dying Comanche Chief—Three Days Later, His Sons Returned With 50 Warriors and Silver

.

.

.

She Nursed a Dying Comanche Chief—Three Days Later, His Sons Returned With 50 Warriors and Silver

The brutal Texas summer showed no mercy that year. Even the vultures seemed to hang motionless in the sky, too exhausted by the heat to circle properly. I stood on my cabin porch, squinting at the horizon where dust devils danced across the parched landscape. My husband Thomas had been gone three weeks, traveling to Austin for supplies and to sell our modest harvest. He should have returned days ago.

I wasn’t a woman who scared easily. Five years on this isolated homestead had hardened me, taught me to handle a rifle as naturally as a ladle. But being alone, with no neighbors for fifteen miles, did something to the mind. Every creak of the cabin, every distant coyote howl, seemed amplified in Thomas’s absence.

That’s when I saw it—a dark shape on the horizon, moving slowly, almost dragging across the dusty plain. Not the purposeful approach of a horse and rider, but something else entirely. I grabbed my rifle and waited, finger hovering near the trigger. As the figure drew closer, I realized it was a man, barely able to stay upright on his horse. Blood darkened his buckskin clothing and long black hair hung limply around a face creased with pain. A Comanche warrior.

My blood ran cold. Stories of Comanche raids haunted every settler in these parts—tales of scalping, torture, and worse. Thomas always said, “If Comanche come, fire warning shots and run for the creek cave. Never engage. Never open our door.” But this was no raiding party—just one man, clearly dying.

The warrior slumped forward, then fell from his horse entirely, landing in a heap not fifty yards from my porch. His horse wandered toward our water trough while the man lay motionless in the dirt. I stood frozen, the rifle heavy in my hands. I could simply wait. Nature would take its course soon enough. No one would blame me. In fact, most would say I’d be a fool to do otherwise. Yet something pushed me forward—perhaps the same stubborn decency that had brought Thomas and me to this unforgiving land in the first place. The belief that a life was a life, regardless of whose it might be.

I approached cautiously, rifle ready. Up close, I saw he was older than I’d first thought. Gray streaked his hair and his face, though twisted in pain, carried the weathered dignity of authority. An arrow had pierced his side, broken off but still embedded. Fever flushed his cheeks.

“I mean no harm,” I said, knowing he likely couldn’t understand. “I’m going to help you.” His eyes fluttered open, dark and intense despite his weakened state. For a moment, fear gripped me again, but then he spoke, his voice a dry rasp. “Water,” in English.

My surprise must have shown because something like amusement flickered across his face before pain claimed him again. I ran to the well, filled a dipper, and returned. Supporting his head, I helped him drink. When he finished, he grasped my wrist with surprising strength. “Quana,” he said, touching his chest. “Sarah,” I replied, pointing to myself.

Getting him inside wasn’t easy. He was tall and, despite his wounded state, heavy with muscle. I half-dragged him, apologizing each time he winced. Once inside, I cleared my kitchen table and managed to lift him onto it. The wound was bad. The arrowhead had lodged between his ribs and infection had set in. I’d helped Thomas remove buckshot and stitch knife wounds before, but this was different. The arrow would need to be pushed through completely—pulling it back would only cause more damage.

I prepared as best I could—boiling water, tearing clean bandages, retrieving the whiskey Thomas kept for medicinal purposes. “This will hurt,” I warned, offering him the whiskey. He shook his head. “No fire water. Medicine song instead.” And to my astonishment, he began to sing—a low, rhythmic chant that seemed to strengthen as it continued.

I took a deep breath, gripped the arrow shaft, and pushed. His song never faltered, even as the arrowhead tore through flesh and emerged on the other side. Blood welled up bright and terrifying, but I worked quickly, breaking off the head, drawing the shaft back through, then pressing clean cloths against both wounds. Only when I began applying a poultice of herbs did his singing stop. He examined the mixture with suspicion.

“Wild onion, yarrow, and comfrey,” I explained, though I doubted he understood. “My grandmother taught me your medicine.” He nodded slowly, then closed his eyes, exhaustion finally claiming him.

I finished bandaging his wounds and sat back, suddenly aware of what I’d done. I had brought a Comanche warrior into my home, treated his wounds. If other settlers knew, they’d call me worse than fool. If his enemies found him here, they might kill us both. But watching him now, his breathing shallow but steady, I couldn’t bring myself to regret it.

There would be consequences. There always were, when you chose compassion over fear. I just couldn’t imagine how far-reaching they would be.

I moved Quana to Thomas’s and my bed—the only one in our small cabin. I would sleep by the fire. As night fell, his fever worsened. He thrashed and mumbled words I couldn’t understand, occasionally crying out names that sounded like “Peter” and “Kahabi.” I bathed his forehead with cool water and spooned broth between his lips when he was lucid enough to swallow.

By dawn I was exhausted, scared I’d made the wrong choices in treating him, terrified the infection would spread. But as morning light filtered through the cabin windows, Quana’s fever broke. His eyes, when they opened, were clear and alert. “You save Quana,” he said—not a question.

“I tried,” I replied. “You’re not saved yet.”

He studied me with an intensity that made me want to look away. “Why?” he finally asked.

It was a fair question. Every story, every newspaper account, every whispered warning around settlement campfires painted the Comanche as merciless predators. Yet here I was, tending to one as I would any neighbor.

“Because you needed help,” I said simply. “And I could give it.”

A slight nod, as if my answer confirmed something he already knew. Then he tried to sit up, grimacing. “Must return. My sons search.”

“Sons?” The word chilled me. If they were searching for him… “How many sons?” I asked, trying to keep my voice even.

“Two warriors. Peter and Kahabi. Many more in camp.”

I swallowed hard. “Will they come looking here?”

“No harm to woman who helps chief,” Quana said. “Chief.” The word hung in the air between us. Not just any warrior, but a leader.

Over the next two days, Quana grew stronger. He couldn’t yet ride, but he could sit up, then stand, then walk slowly around the cabin. He spoke little but watched everything—how I cooked, how I cleaned my rifle, how I marked each passing day on the rough calendar Thomas had made.

On the third morning, as I changed his bandages, he asked about Thomas. “Your husband?” he said, gesturing to the men’s clothing hanging near the fireplace.

“Austin. For supplies. He’s late returning.”

Quana nodded thoughtfully. “Bad men on roads now. Not Comanche,” he added, seeing my expression. “White raiders take horses, supplies.”

That afternoon, as the sun began its descent, Quana suddenly stiffened. He moved to the window, his movements fluid despite his injury. “Riders,” he said. My heart lurched. “Thomas?” But Quana’s posture told me otherwise. He didn’t look relieved or welcoming. He looked weary.

I joined him at the window. In the distance, dust rose from the hooves of approaching horses—many horses.

“My sons come,” Quana said. “With warriors.”

Terror replaced hope. Warriors coming here, to my isolated cabin.

“They will not harm you,” Quana said firmly, reading my fear. “You are now under protection of Quana Parker.”

Parker. The name struck me with the force of a physical blow. Everyone in Texas knew that name—Quana Parker, the feared half-white, half-Comanche chief who led devastating raids across the territory. The man whose name mothers used to frighten disobedient children. And I had him in my home.

“They must see me standing,” he said, straightening despite the pain. “Strong. A chief does not show weakness.”

I helped him onto the porch, where he stood proudly, one hand braced against the post for support. I remained half-hidden in the doorway, my rifle close though I knew it would be useless against so many.

The riders approached—not the rampaging war party of my nightmares, but an organized group. At their lead rode two young men whose resemblance to Quana was unmistakable—his sons. Behind them came warriors, their faces painted, feathers and silver ornaments adorning their horses and weapons. I stopped counting at fifty, my mouth dry with fear despite Quana’s assurances.

The sons dismounted first, approaching the porch with expressions of relief and concern. They spoke rapidly to Quana in Comanche, occasionally glancing at me. Quana replied at length, gesturing once to his bandaged side and several times to me.

Finally, he turned. “Sarah,” he said—the first time he’d used my name since I’d told it to him. “These are my sons, Peter and Kahabi. They thank you for saving their father.”

The taller son stepped forward, holding something wrapped in soft buckskin. With ceremonial gravity, he presented it to me. “For saving chief,” he said in halting English as I took the bundle. “Great honor you bring.”

My hands trembled as I unwrapped the gift. Inside lay a magnificent silver necklace, its intricate design unlike anything I’d ever seen. It glinted in the setting sun, beautiful and alien. I looked up, overwhelmed. Fifty Comanche warriors watched me, waiting for my response. Quana’s dark eyes held a quiet dignity that transcended our differences, the vast gulf between our worlds.

“Thank you,” I managed. “I only did what anyone would do.”

Quana shook his head slowly. “No,” he said. “Not anyone.”

That night, the warriors camped around my homestead, their fires dotting the darkness like earthbound stars. I stood frozen at my window, the silver necklace cold and heavy in my hands, unable to fully believe what was happening. Just days ago, I’d been a lonely settler’s wife waiting for her husband’s return. Now I was hosting Quana Parker and fifty Comanche warriors.

As I prepared a meal for Quana and his sons, I felt their eyes following my movements. Not threatening, but curious—as if I were some strange creature they’d discovered.

“Your people fear Comanche,” Quana said suddenly—not a question.

“Yes,” I admitted, stirring the pot. “I did.”

“Yet you helped.”

“My grandmother once told me that mercy isn’t mercy if it’s only given to those who look like you,” I said finally. “I suppose I wanted to be the kind of person she believed I could be.”

Quana nodded slowly. “Wise woman, your grandmother.”

As we ate, Quana explained the significance of each symbol on the necklace—curved lines for his journey, star-like patterns for his battles, intricate circles for his children. The necklace was more than decoration. It was a living record—a memoir in silver.

By morning, the warriors were ready to depart. Quana, now strong enough to ride, took my hand in farewell. “May your path be straight, Sarah of the healing hands,” he said.

As they rode away, the necklace heavy around my neck, I realized that the boundaries between friend and enemy, settler and Comanche, had forever shifted for me. I had chosen compassion over fear, and in doing so, found myself forever changed.

play video: