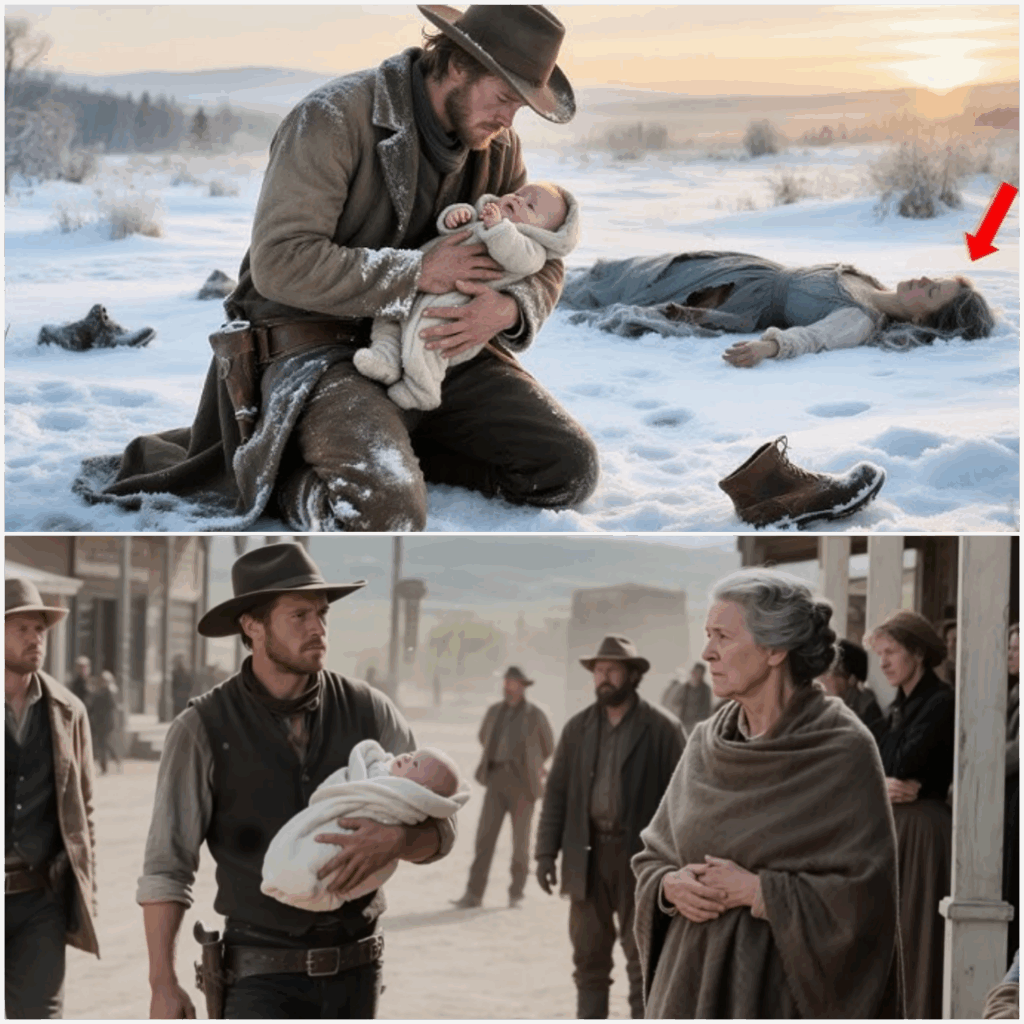

They Found a Baby Beside His Dead Mother in the Snow, But The Tracks Around Them Told Another Story

.

.

They Found a Baby Beside His Dead Mother in the Snow

The storm had passed in the night, leaving the plains hushed beneath a pall of white. The wind no longer howled, yet its memory clung to the air, sharp and bitter, pricking every inch of skin. Snow lay deep across the open land, hiding fences and wagon ruts, softening the hard edges of winter. Crows dotted the sky in black arcs, their wings cutting the silence with harsh cries, and their circling seemed to mark something that did not belong to the stillness.

Jonah Hail came over the ridge, his horse slow and weary beneath him, steam curling from its nostrils. He had spent the last three days in the mountains, cutting firewood, his solitude heavy as the weight of an axe. The snow was no stranger to him. He had known winters where it buried entire cabins, winters where it took men whole. But that morning felt different, as if the land itself was holding its breath.

His eyes, used to the desolation, caught a dark shape by the riverbend, half covered, half exposed. At first he thought it a broken wagon, another piece of the land abandoned to the storm. But then he saw the hand, stiff, pale, pointing upward like it sought mercy from a sky that had given none. He dismounted, boots sinking into the crust of snow, breath misting before him.

The body of a woman lay slumped against the side of a toppled wagon, her hair stiff with frost, her face turned toward nothing. Her eyes, clouded and open, bore the look of someone who had fought too long before surrendering. Snow had gathered at the corners of her mouth, and her skin carried the blue tint of winter’s final claim. She might have been anyone’s daughter, anyone’s sister—a woman whose name would be spoken only in passing once the town heard the tale.

Jonah’s chest tightened, a low ache he did not welcome, for he had already buried enough of his own ghosts. Then the sound came—a whimper, faint and fragile, like the cry of a bird caught in a snare. Jonah’s head turned sharply, scanning the snow. He found it, bundled in worn cloth, pressed against the woman’s still side. A baby, alive, though weak. Its lips cracked, its face flushed raw from the cold. The child’s fists trembled, striking at nothing, and from its mouth came another cry, sharper, desperate, cutting through the silence with all the force of survival.

Jonah’s knees gave slightly beneath him, not from weakness, but from the shock of life clinging in the shadow of death. He reached down, gloved hands trembling more than he would admit, and lifted the child against his chest. Warmth was faint, but it was there, fragile as an ember beneath ash. The baby’s cry settled as Jonah’s coat enveloped it, its face pressed to the wool that smelled of pine and smoke. His heart stuttered. He had once cradled a child like this, his own, only for fever to claim it before the year turned. That memory struck him with an old, merciless pain, and yet his arms did not loosen. If anything, they tightened as though he had been given a second chance he had never asked for.

Jonah looked again at the woman. He searched her face, tried to find resemblance, but there was none he could place. Her hands were calloused, her dress plain, patched in places that spoke of poverty. The snow around them told a stranger story. Deep imprints of boots circled the wagon—scattered and hurried. More than one man had stood there, then vanished into the distance. Whoever left her had not stayed to see her die, nor cared to take the child with him.

Jonah’s jaw clenched as he traced the tracks with his eyes, anger sparking beneath the grief that weighed him. The crows cawed louder overhead, impatient. He turned away, the baby tucked firmly in his arms. He mounted his horse with care, pressing the child against his chest to shield it from the wind. The woman remained behind, half buried already, her face soon to be forgotten under another drift. Jonah tipped his hat to her out of habit, out of respect, though no one was left to see it. Then he rode toward town, each hoofbeat echoing against the silence.

When Jonah entered Milstone, people turned. His presence always drew eyes. He was the man who lived alone, the widower who spoke little, whose grief made him seem older than his years. But that morning, it was not Jonah they stared at. It was the small bundle in his arms. Murmurs rose before he even reached the sheriff’s office, women whispering behind hands, men spitting into the snow with narrowed eyes. Milstone was a place that measured worth by appearances, and the sight of a widowed rancher carrying a baby no one claimed was a scandal waiting to ignite.

Mave Callahan stood at the steps of the church, her shawl drawn tight, her lips pursed like a trap waiting to spring. She was the keeper of tongues in town, the one who could spread a story faster than the wind carried smoke. She leaned on her cane and squinted at Jonah. “Whose child is that?” she asked loud enough for all nearby to hear. Her voice carried the tone of accusation, as though the baby itself had sinned.

Jonah kept walking, his silence a shield, but Mave was not done. “A woman dead in the snow and you ride in with her babe. Folk will wonder what part you played in it, Jonah Hail. They surely will.” He stopped slowly. He turned his face to her, eyes cold as the ice on the eaves. “I played no part,” he said quietly, “save for picking him up before the cold did.” His voice was gravel-low but steady. Yet even that simple truth did little to quiet the whispers.

Sheriff Dillard came striding from his office, boots crunching on the frozen ground, his badge catching what little light broke through the clouds. He was a man who valued order over compassion, law over grace. He looked at Jonah, then at the child, his brow furrowed. “This baby ought to be placed proper,” he said. “The church can tend to him until kin are found.”

Jonah shook his head. “Church has no milk, no fire warm enough to keep him through the night. He stays with me till more is known.” The sheriff’s jaw tightened, but Jonah’s tone left little room for argument. Still, murmurs swelled among the gathered crowd. Some whispered that Jonah wanted to claim the child as his own. That perhaps the dead woman had been his secret. Others shook their heads, muttering of curses and ill-omen, how sorrow followed Jonah like a shadow that could not be outrun.

The baby squirmed, its small whimper cutting through the noise, and Jonah pulled his coat tighter around it, shielding it as though the town itself were another storm. That was when Miriam Cade stepped from the store porch, basket in her hands, her eyes steady though her cheeks burned against the cold. She was known in Milstone, though not kindly, left humiliated when her fiancé abandoned her for another, her name carried in gossip as if shame itself had taken her hand. Yet she came forward, her voice clear, though soft enough not to sound like defiance. “He’s right,” she said, nodding toward Jonah. “The child won’t last in the church, not in this cold.” Her gaze shifted to Jonah’s, holding it. “If you need help, I’ll bring milk.”

The crowd’s whisper shifted. Some sneered, others laughed bitterly. Two disgraced souls standing together with a baby no one wanted. It was fodder enough to last a winter. Mave Callahan’s mouth curved into a knowing smirk. “Figures,” she muttered. “Birds of a feather.”

Jonah’s eyes lingered on Miriam. He had seen her before, always from a distance, her hair catching light like copper against the drab walls of town, her shoulders squared even when whispers burned her back. There was something in her gaze now—not pity, but something steadier, something that seemed to steady him in return. He gave the faintest nod, and with that turned and carried the child toward the edge of town. Miriam followed a step behind, ignoring the weight of eyes pressing against her.

His cabin lay a mile out, half hidden in the pines, smoke already curling from the chimney where he’d left a fire banked. Inside, the warmth felt like salvation after the bite of the wind. Jonah laid the baby near the hearth, wrapping him in an extra quilt. The child’s cries softened, though hunger remained in the way his tiny mouth searched. Without word, Miriam placed her basket down and withdrew a small tin of goat’s milk she had brought. She warmed it by the fire, then dipped cloth into the liquid, pressing it gently to the baby’s lips. Slowly, eagerly, the child sucked, life reasserting itself in fragile gulps.

Jonah watched, the sight of her holding the child stirred something old, something he had thought winter had buried in him long ago. Miriam’s face, lit by the flicker of firelight, bore no trace of judgment, no trace of fear, only the simple tenderness of someone who chose to stay when others had turned away. For a moment Jonah forgot the gossip, forgot the sheriff’s stern gaze. All he saw was a child breathing easier, and a woman whose presence softened the silence of his cabin. The baby let out a small sound, half sigh, half gurgle, and Miriam smiled faintly. Jonah’s chest tightened at the sight, though he gave no word to it. His grief still sat heavy. But beneath it, something shifted, like earth cracking to let through the first green shoot of spring. He did not dare name it. Not yet.

Outside, the wind stirred again, carrying with it the echo of voices from town. Judgment would not rest easy. Already stories were forming, hardening into truth whether or not they bore it. Jonah knew that the snow buried tracks only until thaw came, and when thaw came, what lay beneath would demand reckoning. He looked toward the shuttered window, then back to the child who slept between them, its small chest rising and falling, fragile as hope itself.

Miriam’s eyes lifted to his. “What will you do?” she asked softly. Jonah did not answer. His silence was not refusal, but wait—the weight of knowing the storm was not behind them, but ahead. He stared at the sleeping child, then at the faint tracks of snow melting from his boots across the floor. Tracks that led into his cabin. Tracks that others would follow. And in that silence, in the crackle of fire and the hushed breath of winter beyond the walls, it became clear the baby was not the only one who had been found in the snow.

The baby’s cries had become part of the rhythm of Jonah’s cabin, like the crackle of the fire or the creak of pine logs settling in the frost. Each sound tethered him to the present, refusing to let him drift fully into silence. Miriam came often now, her steps soft against the snow outside, her hands carrying milk or bread, sometimes nothing more than her presence. Between them grew no declarations, no spoken promises, only the quiet exchange of tasks, the shared tending of the fragile life they sheltered. Yet beneath those gestures, something deeper stirred, as undeniable as the thaw that waits beneath ice.

Still, the town did not forget. Whispered words carried further than winter winds. “He keeps the child as if it were his. She lingers there too often. Shame upon shame.” The judgments tightened like ropes, invisible but heavy. Jonah bore them with the stillness of a man used to weight. But he saw how Miriam lowered her gaze in town, how her cheeks flushed, though her eyes remained proud. They lived in a place where a woman’s worth was measured by gossip, and gossip could strip her to bone.

One morning, Sheriff Dillard came to Jonah’s cabin. His knock was not polite, but heavy, demanding. Jonah opened the door to find him standing tall, snow dusting the brim of his hat. The sheriff’s eyes flicked to the cradle near the fire where the child slept, then to Miriam, who sat beside it. His mouth set into a thin line. “This can’t go on,” he said. “A babe without kin must be taken to the church. It’s the way of order.”

Jonah’s jaw tightened. “The church cannot feed him. Miriam and I can.”

The sheriff’s gaze hardened. “Folks are talking, Jonah. They say you’ve claimed what was never yours. That the dead woman belonged to you and this is your doing.” The words struck not for their truth, but for their cruelty. Jonah stepped closer, his voice low. “I buried my wife in this ground three winters past. Do you think I’d leave another woman to die?” His hands shook despite his calm, and Miriam, seeing it, rose and touched his arm, not to hold him back, but to steady him.

The sheriff’s eyes lingered on that small gesture, his disapproval clear. “This town won’t abide shadows, Jonah. Bring the child to the church before shadows turn to storm.” With that, he turned and left, his tracks crisp in the snow.

For days after, Jonah’s silence grew heavier. He did not speak of the sheriff’s threat, but Miriam felt it in the air, saw it in the way he lingered by the window, eyes on the horizon. One evening when the baby had finally slept, she broke the quiet. “They’ll come again,” she said. “And if they do, we must be ready. Not with anger, Jonah. With truth.”

He met her eyes. “And what truth will they hear? They’ve already decided what they want.” His voice carried the weariness of a man who had lived long under judgment. Miriam reached for the quilt, covering the baby, smoothing it with care. “Then we’ll show them,” she whispered. “Tracks don’t lie. You said it yourself.”

The words stayed with him. That night, as the fire burned low, Jonah remembered the snow at the wagon, the scattered boot prints, the hurried steps that vanished into the distance. He had left too quickly, taken by the urgency of the child. But the truth of those tracks remained, waiting.

The next morning, he saddled his horse. Miriam looked at him with quiet knowing. “You’re going back,” she said. He nodded once. She wrapped her scarf tighter and stepped outside with him. “Then I’ll ride with you.”

The land had grown harsher since the storm. Snow lay deeper, crusted by wind, but the old tracks still showed, faint but unforgotten. Jonah dismounted and knelt, brushing aside frost with his glove. Boot marks, more than one set, heavy and deliberate. He followed them with his eyes, tracing where they circled the wagon, where they paused near the woman’s body, then turned away. The story was written clear. She had not been alone when she died. Someone had left her there, abandoned with a child.

Jonah’s breath caught, anger rising. He stood, fists clenched. Miriam watched, her eyes soft but resolute. “Then she was not simply lost to the storm,” she said quietly. “She was left to it.”

Jonah looked toward the horizon, the baby’s face flashing in his mind. Whoever had done this walked free while the town whispered blame upon him and Miriam. It was a weight he would not bear. “The tracks tell the truth,” he murmured, “and truth must be carried back.”

They returned with the evidence etched in their memory, though not all in town cared for proof. Mave Callahan stood at the well, her voice sharp as she called after Miriam. “Still running to his cabin? Are you a woman with no husband? A man with a bastard child. What do you think folk will see?” Miriam did not answer. Her silence was not surrender, but defiance, though it cost her more than words could tell.

That evening, Jonah gathered his resolve. He went to the sheriff’s office, Miriam beside him, the baby cradled close. A small crowd formed, drawn by the scent of conflict like wolves to blood. Jonah placed his hands on the desk, his voice firm but calm. “I found the woman’s wagon. I saw the tracks. More than one man was there before she froze. They left her, sheriff. That’s the truth.”

The sheriff studied him, unmoved. “And yet it was you who rode in with the child. You who shelter him still. Truth can be twisted by a man’s need.”

Murmurs rose. Mave’s voice rang above them. “He hides behind silence, but silence is guilt.” Others nodded, eager for scandal. The baby stirred, whimpering, and Miriam held him closer, her jaw tight as the words struck her like stones.

Jonah turned, his eyes sweeping the faces of those who judged. His silence held for a long breath, then broke, not in anger, but in a voice steady, weighted with sorrow. “You say silence is guilt. I say silence is survival. I buried a wife three winters past. I lost a child before he could speak. Do you think I’d leave another woman to die? Her babe beside her. If you believe that, you know nothing of me.” His words were low, but they carried, cutting through the noise with the raw edge of truth.

The sheriff shifted uneasy. The crowd faltered. For a moment the weight of Jonah’s grief stilled them. Yet still Mave sneered. “Words are easy, Jonah Hail, but words don’t make you fit to keep a child. Shadows follow you. And her.” She pointed at Miriam. “She’s already lost her name in this town.”

The insult struck like a lash, but Miriam did not flinch. She stepped forward, her voice clear, though her hands trembled around the child. “If I have no name here, then let me have this one thing, the care of a child no one else will hold. Shame does not kill, Mave Callahan. But cold does. Hunger does. I’d rather be called shameless and keep him alive than stand by in judgment while he dies.”

Her words fell into silence. Even the sheriff looked away, his face taut. Jonah felt something within him ease, though his body remained rigid, ready for their scorn. The baby stirred again, let out a faint cry. It was that small sound, not Jonah’s grief nor Miriam’s defiance, that carried the final weight. The town, for all its cruelty, could not deny life when it spoke.

Sheriff Dillard cleared his throat. “Tracks tell a story,” he admitted at last, “and the story is not yet clear. But no man or woman here can claim you’ve brought harm. The child stays for now.” His words were reluctant, but they held authority. The crowd shifted, their whispers subdued. Mave’s mouth pinched shut, her victory denied.

Jonah exhaled, though it did not feel like triumph. It felt like reprieve, temporary and fragile. He turned to Miriam, their eyes meeting, no words passed, but the weight of shared defiance bound them tighter than speech. Together, they carried the baby out of the sheriff’s office, out of the crowd’s gaze, into the cold evening, where the sky burned faintly with the last light of day.

The walk back to the cabin was quiet. The snow crunched beneath their boots, the baby’s breath warm against Miriam’s chest. Jonah walked beside her, his hand brushing hers once, not by accident, but by choice. She did not pull away. The silence between them no longer felt like guilt, nor like judgment. It felt like promise.

That night, the fire burned low, casting long shadows across the room. The baby slept between them, his small chest rising and falling. Jonah sat back, eyes on the flames, the memory of the wagon heavy in his mind. Miriam’s voice broke the quiet, soft but steady. “You carried him from the snow, but maybe he carried you, too.”

Jonah looked at her. The firelight painted her face with warmth, softening the lines of weariness. He did not answer, but the truth of her words settled deep. His grief had been a cage, but the child had forced the door open, and Miriam had stepped through with him.

Outside, the wind shifted, carrying the faint echo of crows. The tracks in the snow would remain until spring, but within the cabin, something stronger had taken root. Jonah leaned forward, adjusting the quilt over the child. His hand lingered a moment, then withdrew. Miriam watched, her eyes catching his, and for a breath neither looked away. The silence between them pulsed, filled not with judgment, but with the unspoken knowledge of what they had chosen together.

The fire cracked, a log collapsing inward, sparks rising. Beyond the window, darkness stretched wide, and in that darkness the weight of the town still waited. But here, for this night, they had carved a light. And though Jonah did not yet know where the tracks would lead, he knew this: he would not walk them alone.

End of story.

.

play video: