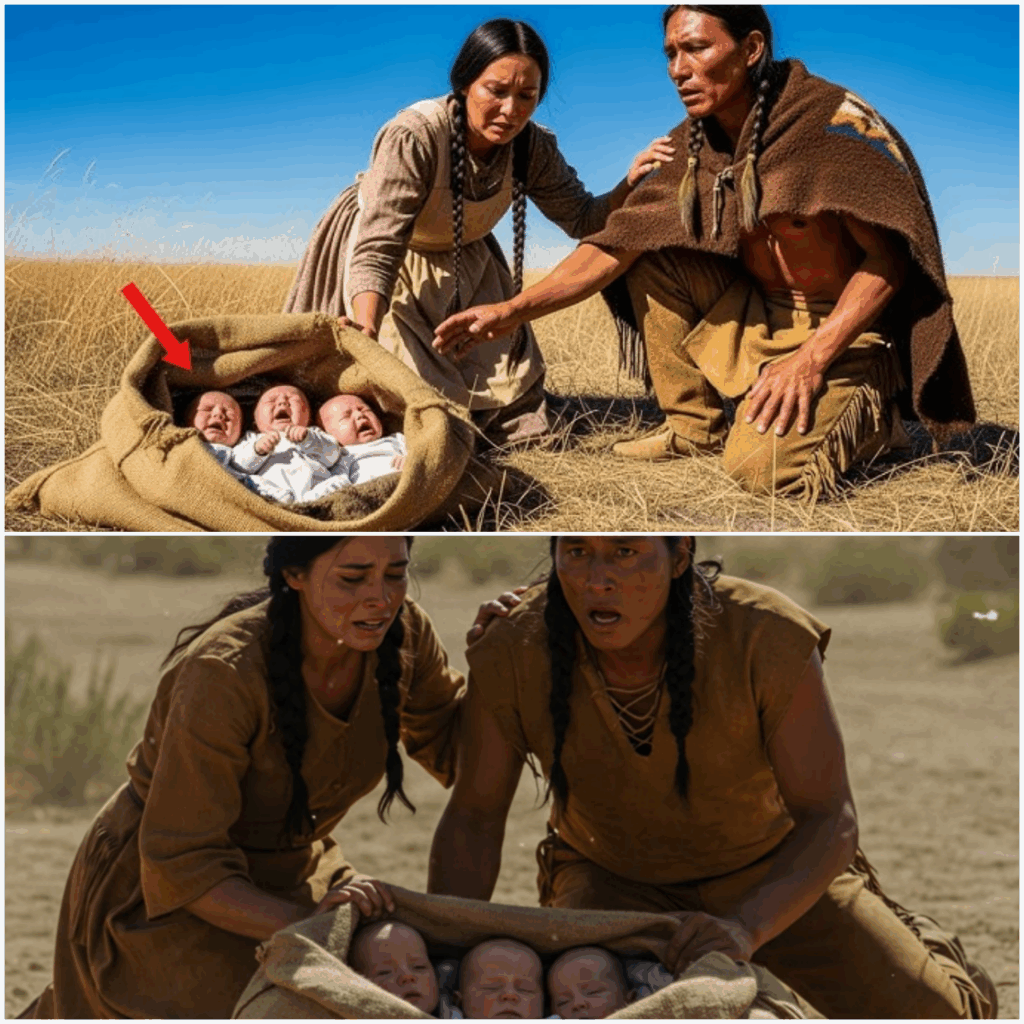

Three White Babies Were Abandoned in a Sack to Die – But Then an Infertile Native Indian Couple…..

.

.

Three White Babies Were Abandoned in a Sack to Die – But Then an Infertile Native Indian Couple…

The silence of the land was a language Chaitton understood. It spoke in the sigh of the wind through the sparse pines clinging to the Dakota hills, in the distant, lonely call of a hawk circling beneath a vast, indifferent sky. It was the same silence that had settled into his and Winona’s sturdy, one-room cabin—a quiet heavier than emptiness, a hush that pressed on their hearts for a decade. For ten years, the silence had been a ghost, haunting their home with the children they prayed for but never had.

In the autumn of 1887, their grief was a well-worn stone, familiar and cold in their hands. Chaitton, a Lakota hunter, lived with his wife in a shallow valley carved by a creek that ran thin in summer and froze solid in winter. Their life was one of necessity and routine—Chaitton hunting and trapping, his footfalls sure and quiet on the earth, and Winona coaxing life from the stubborn soil, her hands skilled with roots and herbs, her knowledge passed down from her grandmother. They moved around each other with the deep, unspoken understanding of two people who had weathered the same long storm. Love was there, deep and abiding, but shaded by sorrow—a garden touched by a permanent frost.

That morning, the air was crisp, carrying the first bite of autumn. Chaitton was checking his line of snares along the creek bed, the rising sun casting long, cool shadows. He moved with practiced economy, senses tuned to the world around him. He noticed the scrape of a deer’s hoof, the agitated chatter of a squirrel, the way the light fell on the water. It was this attention to small things that had kept him grounded, that gave him purpose when the larger hopes of his heart had withered.

He had collected a pair of rabbits when he heard it—a thin, reedy sound, almost lost beneath the murmur of the creek. At first, he dismissed it as a kit fox or a distressed bird. But the sound came again—a wavering, desperate cry that snagged on something deep inside him. It was not the sound of any animal he knew. It was too raw, too fragile. It sounded almost human.

A cold knot of unease tightened in his stomach. He left the rabbits where they lay and followed the sound, his moccasins making no noise on the damp earth. The cries led him downstream toward a thicket of willows where the bank eroded into a shallow cut. There, half hidden in the tall grass, was a coarse burlap sack, tied shut at the top with rough twine, and moving—a small, frantic stirring from within.

Chaitton’s heart hammered against his ribs. He approached with caution, his hand resting on the knife at his belt. The smell that met him was sour, a scent of neglect and fear. The crying had subsided into weak, hiccuping mewls. He knelt, eyes scanning the area for any sign of who had left it. There was nothing—only the indifferent trees, the flowing water, and this terrible living bundle.

With deliberate movements, he pulled his knife and sliced through the twine. The mouth of the sack fell open. He peered inside, his breath catching in his throat, his mind refusing to process what his eyes were seeing. The silence he had known his whole life was nothing compared to the one that now roared in his ears.

Cradled in the foul darkness of the sack, tangled in a thin, soiled blanket, were babies—not one, but three. They were impossibly small, their skin pale and mottled with cold, their faces pinched and blue around the lips. Their tiny chests rose and fell in shallow, shuddering breaths. As the cool morning air hit them, one let out another weak, plaintive wail, a sound so full of helpless misery it broke through Chaitton’s shock and pierced him to the core.

He stood frozen for a long moment, the world tilting on its axis. This was not his world. This was a sorrow from the white man’s town, a cruel secret discarded in the wilderness to be erased by the elements. His first instinct was cold pragmatism. Taking these children would invite a world of trouble he and Winona had always sought to avoid. He should walk away. He should let the wilderness do what it was meant to do.

But then he looked at their faces. He saw a tiny hand, no bigger than a leaf, clench and unclench. He saw the flutter of eyelashes against a sallow cheek. He thought of Winona, of the ten years of silent tears she had shed into her pillow at night, of the cradle he had carved for their first hope, now gathering dust in the rafters. This was a cruel trick of the spirits, or perhaps, something else entirely.

He could not leave them. Whatever the cost, whatever the danger, he could not be the man who walked away and left them to die. With a resolve that settled deep in his bones, Chaitton gently gathered the corners of the thin blanket, lifting the three tiny, fragile bodies from their grim container. They were so light, their collective weight less than a single sack of flour. He cradled them against his chest, their faint warmth a flickering ember, and turned for home.

Winona was scraping carrots from her garden when she saw him coming. She rose, wiping her soil-stained hands on her apron, a question in her eyes. She expected to see him carrying game, but he was empty-handed except for the strange, bulky bundle he held so carefully. His face was a mask of stone, but she knew him better than she knew herself. She saw the turmoil in his jaw, the conflict in his dark eyes.

“Chaitton,” she called softly, “what is it? Are you hurt?” He did not answer until he stood before her on the small, swept earth patch that served as their porch. He looked at her, preparing her. Then slowly, he folded back a corner of the blanket.

Winona’s breath left her in a silent gasp. Her eyes widened, first in disbelief, then in dawning, horrified comprehension. She saw the three tiny pale faces, the listless limbs, the utter vulnerability. Her hand flew to her mouth. For a moment, the world swam before her. All the years of yearning, of empty arms and a silent womb, rushed up to meet this impossible, heartbreaking reality.

“These are the ghosts of my own lost dreams, made flesh and blood and left to perish,” she whispered. Her first thought was a wave of old pain, so sharp it was like a physical blow. Why show her this? Why bring her the one thing she could never have, only to present it in such a state of tragic abandonment?

But as she looked, the pain began to transform. It melted away under a fierce, hot surge of something else. It was not pity. It was a primal, protective rage. She saw not the color of their skin, nor the circumstances of their arrival. She saw only life, flickering and fragile, on the verge of being extinguished. She reached out, her fingers cool from the garden soil, gently touching the cheek of the smallest baby. The skin was cold.

“Bring them inside,” she said, her voice no longer trembling but filled with a sudden, unshakable authority. The question of what to do, of whether to keep them, did not exist in her mind. They were here. They were alive. Her purpose, which had felt so lost for so long, was now blindingly clear.

The cabin, once a haven of quiet sorrow, instantly became a crucible of desperate activity. Winona directed Chaitton with a swift, certain energy he had not seen in her for years. They laid the babies on a soft buffalo robe near the hearth, where a low fire burned. Winona gently unwrapped them from the foul blanket, her hands moving with an instinct she did not know she possessed. They were two boys and a girl. She washed them with warm water and soft cloths, wrapped them in the linen she had saved for a future that never came, and bundled them together for warmth.

“They need milk,” Chaitton said, the words heavy with the near impossibility of their situation.

“The Prescotts’ goat just kidded. They may have extra milk,” Winona replied, her focus entirely on the infants.

The Prescotts were white settlers a few miles east. They were not unkind, but wary. Going to them with three abandoned white babies was a risk, an invitation for questions and suspicions. “Winona,” he began, “you know what they will say. What they will think.”

“They are dying, Chaitton. Do their thoughts matter more than this?” she shot back, her eyes blazing.

He saw in her face not just the wife he loved, but a woman reborn. “I will go,” he said simply, and rode to the Prescotts’ homestead, trading a fine rabbit pelt for a precious pail of milk.

The days that followed blurred into exhaustion and relentless care. The cabin was transformed. The quiet was replaced by the thin, demanding cries of the infants. The slow, predictable rhythm of Chaitton and Winona’s life was shattered, replaced by constant feeding, cleaning, and soothing. They learned to tell the cries apart. The girl, whom Winona named Otooka—“blossom”—had a fretful, insistent wail. The larger boy, Kangi—“raven”—had a lusty, demanding cry. The smallest boy was the quietest, frail, his hold on life tenuous. Winona called him Tio—“dwelling”—praying he would choose to dwell among them.

Their precarious peace could not last. Word of Chaitton’s daily trips for milk spread. A week after they found the babies, the town sheriff, Henry Shaw, rode out to their valley. He was a large man who carried his authority like a heavy coat. He did not dismount immediately, his eyes taking in the homestead with a critical gaze.

“Been hearing strange talk about you buying up goat’s milk every day,” the sheriff said.

“It is not forbidden to buy milk, Sheriff,” Chaitton replied evenly.

“It is when a man and his wife who have no children suddenly need enough milk for a litter of pups.”

The sheriff pushed open the cabin door and stopped. Winona was burping a tiny pale-skinned baby. In the crate beside her, two other infants slept. The sheriff’s face cycled through shock, confusion, and suspicion.

“These are white children. They don’t belong here with you.”

“They belong with those who keep them alive. They belong with those who love them. We are those people,” Winona said, her voice steady.

The sheriff was taken aback by her fire. He looked again at the babies, at the neat stacks of linen, the pot of milk warming by the hearth. There was only care here.

“There’s a man in town—Garrett Vance. One of his serving girls disappeared a little over a week ago. Rumor was she was in the family way. He’s been asking questions.” The sheriff’s warning was clear: danger might come looking for these children.

Days later, Vance arrived with armed men, demanding the children he called “property.” Chaitton and Winona stood their ground, rifles ready, refusing to give up the babies. A violent standoff ensued, but just as things turned bleak, the sheriff and local homesteaders arrived, siding with the couple. Vance was exposed for his crimes and met justice at the sheriff’s hand.

In the years that followed, the valley remained their sanctuary. Suspicion softened into respect. Chaitton and Winona raised the three children as their own, teaching them the ways of the Lakota and the white world alike. Their home was no longer silent, but filled with laughter, scraped knees, and the vibrant pulse of life.

One evening, as the sun set behind the hills and the children played by the creek, Winona leaned her head on Chaitton’s shoulder. “The spirits were not cruel that day,” she said softly.

Chaitton looked at his family, his heart full. “No,” he agreed, “they were giving us back our lives.”

End of story.

.

PLAY VIDEO: