“Your Daughter Needs A Father, My Newborn Daughter Need Breastfeed” Giant Rancher Proposes To Widow

.

.

.

Your Daughter Needs a Father, My Newborn Daughter Needs Breastfeeding: A Giant Rancher Proposes to a Widow

The morning sunlight crept slowly across the warped boards of the train station platform, picking out the dust in golden rays. The small town was just waking, voices rising in sharp bursts as townsfolk gathered to greet the arriving stagecoach. Amid the bustle sat a woman with weary eyes, her head bowed beneath a faded bonnet, the ribbon limp and frayed. In her arms, she cradled a newborn, swaddled and silent, too new to fuss, too tired to cry. Beside her, a barefoot two-year-old girl clung to the hem of her skirt with one hand, a limp ragdoll in the other, thumb tucked in her mouth, watching boots and skirts shuffle past.

They had walked the last miles into town, her shoes worn thin, the road dust clinging to her dress in pale streaks. She had not expected kindness here. Towns were all the same—quick to see what you lacked before they saw what you carried. She sat on the edge of the water trough, shifting the newborn against her shoulder. The child’s breath was quick and shallow, as though afraid to take too much of the air around her. The mother pressed her cheek to the small, downy head, trying to will her own warmth into that fragile body.

Across the street, a man stood in the shadow of the livery. He was tall—taller than any man she’d ever seen—broad through the shoulders, his hat pulled low, one hand resting on the rail. His eyes found her through the space between wagons, steady and unreadable, but not cold. Something in his stance didn’t fit the rest of the street’s indifference, as if he were holding himself back from crossing over.

A woman in a starched bonnet passed, her gaze flicking over the barefoot child, the dust on the mother’s skirt, her mouth pressed thin. “Shame,” she muttered, loud enough to be heard. The two-year-old’s hand tightened on the ragdoll, her eyes seeking her mother’s face for comfort. The baby stirred, a faint mewl, and the woman’s body went rigid—hunger, not the kind she could fix with the coins rattling in her skirt pocket. Enough for bread, maybe, never for what the child truly needed.

The man moved then, slow steps across the street, boots scuffing the dirt. Up close, his shadow fell over her, blocking the sun. His voice was quiet, carrying more weight than volume. “Ma’am.” She looked up long enough to see the grief set deep in the lines beside his mouth. His gaze dropped to the newborn, then back to her. “My wife,” he said, voice rough. “She passed yesterday. The girl she brought into the world—she’s still here. Hungry.”

It took her a moment to understand. His voice softened further, careful and deliberate. “I’ve been told there’s no one in town can feed her. I saw you had a little one of your own. I thought maybe…” Her arms tightened around her own baby. Milk was not something she’d ever thought she’d be asked to share. Her pride rose fast, what was left of it, but so did the ache in her chest when she pictured a child alone, unfed.

The toddler at her side tugged her skirt. “Mama.” She looked back at the man. He was not pleading. He simply stood there, waiting, as if whatever answer came, he would accept it. That stillness unnerved her more than if he’d begged.

“Show me,” she said at last.

His eyes flickered—the smallest shift of relief—and he nodded once. She rose, knees stiff, the baby shifting in her arms. The toddler kept hold of her skirt as they followed him down the side street. The sounds of the main road faded away until there was only the crunch of their steps on gravel. They stopped outside a small house, plain boards weathered silver, a porch sagging just enough to give it a weary look. On a cot near the doorway lay a bundle, tiny fists tucked up by her chin, mouth working silently against the air.

The woman knelt, easing the newborn from the blankets. The child was lighter than she expected, the weight barely there. She settled onto the porch, adjusted her own baby, and drew the stranger’s daughter close. The latch was instant, desperate. The man’s hands curled into fists, then slowly loosened, his shoulders lowering as he let out a breath. He turned away, perhaps to give her privacy, perhaps to hide the shine in his eyes.

The two-year-old climbed onto the porch beside her mother, setting the ragdoll carefully between the babies as if it were an offering. The air held stillness then, not the brittle kind before a storm, but the softer kind that follows a long stretch of noise. When it was done, the woman shifted the child back into her blankets. The man’s hands were gentle when he took her, cradling her as though afraid she might vanish. His gaze held hers, searching for something—permission, trust, maybe both.

“You’ve saved her life,” he said.

Her throat worked, but no answer came. She rose, lifting her own baby, the toddler’s hand slipping into hers. She turned to leave, but his voice followed.

“I could use help with both girls.”

She stopped. The street ahead was empty, the sun glinting off the dusty road. Behind her, his words hung in the air, heavy with more than their simple meaning. She did not turn back. Not yet. But her grip on her daughter’s hand tightened, and the ragdoll lay forgotten on the porch between them.

The next morning, the light came warmer, spilling across the dirty yard and catching on the dust that hung in the air like breath that wouldn’t settle. She sat on the porch rail with her two girls, the newborn swaddled and sleeping, the older one swinging her bare feet and tracing patterns in the wood grain. She had meant to leave before the town stirred, but his shadow stretched long across the yard before she could rise.

He came with no hat today, the sun striking the tawny strands in his hair, a paper-wrapped bundle in one hand, a water jug in the other. “I figured you hadn’t eaten,” he said, setting the bundle beside her. Inside was a heel of bread, a slab of cheese, and two boiled eggs. The weight of the food in her lap brought a rush of gratitude she didn’t want him to see, so she kept her eyes on the bread as she tore it. The older girl took her share without a word, crumbs sticking to her lips.

He didn’t sit, but leaned against the porch post, gaze fixed on the horizon as if measuring something out there against what stood in front of him. “How’s she?” he asked, nodding to the newborn. “She’s breathing,” she said. It was all she could offer without letting the truth leak through—how thin the baby felt, how she’d checked her color in the night more than she slept.

He shifted, pushing a breath out slow. “Mine—the one you fed. She cried half the night after you left.” His voice caught for a beat before it steadied. “It’s been less since she got milk in her. But she’ll need more.”

The request wasn’t sharp, just plain, the way a man might speak of the weather. Still, it carried weight. She looked down at her own child, heavy and warm against her, and felt her body tense. Milk was part of her, not something she’d ever thought to give away. Yet she remembered the other child’s rooting mouth, the way her tiny fists had trembled, and the ache in the man’s eyes as he’d watched.

“You’re asking me to feed her regular,” she said.

“I’m asking,” he said simply, “for her life.”

Finally, she nodded. “Slow. Bring her.”

When he came back with the baby, he carried her as if she were glass. The child’s eyes were shut, lashes dark against skin pale as paper. She made a small noise when placed in the woman’s arms, and the sound pierced something in her chest. She settled on the porch step, guiding the other baby to her breast. The latch was quick, hungry, and the rhythm soon steadied into something quiet, almost reverent.

The man crouched nearby, forearms braced on his knees, watching with an expression that shifted between relief and something deeper, something he didn’t seem ready to name. “She looks stronger already,” he murmured.

“She just needs time,” the woman said, though part of her feared there wasn’t much to give. They stayed like that until the child’s small body went slack in sleep. She passed her back to him, and his hands cupped the tiny form with the same care he might give a bird that had fallen from its nest.

“You’ve done more than you know,” he said, his voice low.

She rose, brushing crumbs from her skirt. “Don’t thank me yet.”

He straightened the baby against his chest. “I will, in my own way.”

Her older girl tugged at her skirt, holding up the ragdoll. “Can she come play at our house?” she asked, glancing at the man.

The question made the woman’s breath hitch. Us. They didn’t have a house, not really. Just walls borrowed from luck or pity until the wind changed. He looked at the child and smiled, the faintest bend of his mouth. “Maybe,” he said.

When he left, the yard felt quieter, but not emptier. She sat back on the porch rail, the newborn in her arms stirring. A breeze carried the smell of pine and horses from somewhere beyond the street. She hadn’t planned to stay. She hadn’t planned for any of this. But as she looked down at her baby, she realized the man’s eyes had not been filled with charity. They had been filled with something far rarer on the frontier—recognition.

That night, after her daughters had fallen asleep curled against her, she lay awake listening to the slow tick of the clock in the corner, the memory of his voice echoing in her mind. When the knock came at the door just before dawn, she already knew it would be him. The knock was soft but certain, like a man who knew he was welcome enough to wait.

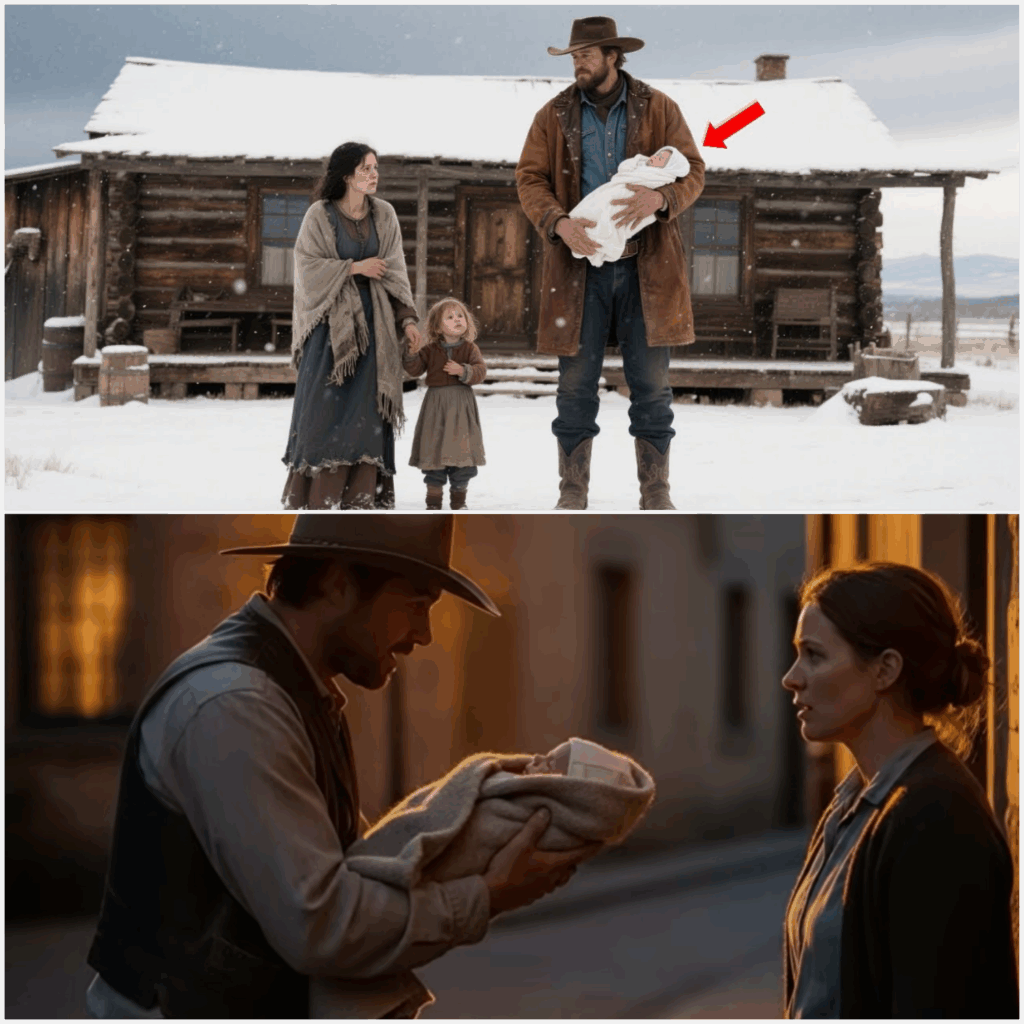

She opened the door to find him standing there, the early light painting the dust on his coat a muted gold. In his arms was the infant, bundled in a wool blanket, eyes closed and mouth working in her sleep. “I thought maybe—” His words trailed off, and instead of finishing, he stepped aside, letting her see the wagon behind him loaded with a few sacks of grain, a crate of apples, and a narrow wooden cradle with a thin quilt folded inside.

She glanced from the load to him. “That’s a lot for one feeding.”

His mouth curved faintly. “It’s for more than one.”

By noon, they had walked the mile to his land. It spread wide under a sky that seemed larger than the one above town, the grass bending in waves to the breeze. A weathered cabin stood at the far edge, boards gone silver with age, roof patched with care. She paused at the threshold, her two-year-old clutching her skirt, the newborn in her arms.

“Go on in,” he said, pushing the door open. The scent of pine boards and old smoke drifted out. Inside, sunlight angled through the small windows, falling across a table scarred with years of meals and hands. A stone hearth held the faint ghost of a fire. It was spare but clean, and something in her ribs eased without her permission.

He set the cradle by the bed, his big hand surprisingly gentle as he tested the rock of it. “This room’s yours. If you want it, I’ll take the loft.”

Her instinct was to refuse. Rooms came with expectations always, but the sight of the cradle, empty and waiting, made the word catch in her throat. She lowered her newborn into it, watching her tiny chest rise and fall. The older girl toddled around the cabin, her small fingers brushing the edges of chairs, the cool metal of a tin cup, the smooth handle of a rocking chair. She stopped by the hearth, looking up at the man.

“Can we make fire?”

He crouched to her level. “Later, when it’s dark enough to see it dance.”

The afternoon passed in a quiet rhythm. She fed his child while her own slept, the sound of the baby’s swallowing a soft counterpoint to the creak of floorboards as he moved about, bringing in wood, setting apples in a bowl. He didn’t linger over her shoulder, didn’t fill the air with questions or instructions. When she finished, he took the baby back, tucking her into the crook of his arm with a tenderness that seemed to slow his whole frame. He sat in the rocking chair, the baby against his chest, eyes on the fireless hearth, as if he could already see the flames.

She made a simple stew from the grain and apples, the scent filling the small room. It had been months since she’d cooked in a place that didn’t feel borrowed. When she set the bowls on the table, he joined her without hesitation, waiting until she sat before lifting his spoon. They ate in companionable silence, broken only by the sound of the older girl humming to herself as she dipped bread into the broth. There was no talk of arrangements or debts, just the scrape of spoons, the low sigh of wind against the cabin walls, the rare sense that no one here needed to prove their place.

After the meal, she stepped onto the porch. The land stretched open before her, the sky wide and unbroken. From here, the town was a faint smudge on the horizon, its voices too far to reach. The quiet wrapped around her, not empty, but whole. He joined her, standing with one shoulder against the post. The baby in his arms slept deeply, her small hand curled into his shirt.

“You could stay,” he said, his tone steady, as though it were neither an order nor a plea.

Her fingers tightened on the railing. “For how long?”

“As long as it takes.”

She turned her head toward him. “For what?”

His eyes met hers, steady and unflinching. “For all of us to breathe easier.”

The older girl came out then, tugging at her mother’s skirt. “Mama, look.” She held a pine cone cradled in both hands like it was treasure. The woman crouched, brushing a strand of hair from the child’s face. “Where did you find that?”

“By the door,” the girl said, glancing between them.

The man smiled faintly, watching the exchange. “She’s already making this place hers.”

The sun began to sink, laying long shadows across the grass. He lit the fire as promised, and they all sat near it, the children drowsy, the air warm with the scent of pine resin. Later, when she carried her daughters to the bed and returned to the hearth, she found him still in the rocking chair, his gaze fixed on the flames.

“Why me?” she asked quietly.

He didn’t look up. “Because you didn’t look away.”

The fire popped softly. She felt the weight of his words settle over her, not heavy, but sure like the roof above them. When she finally went to bed, the cradle was between her and the wall, both babies breathing in the same slow rhythm. She lay awake listening to it. In the loft above, a floorboard creaked. Then his voice, low in the dark, carrying just enough for her to hear: “This feels like the first right thing since she died.”

The days began to fall into a gentle rhythm. Morning light slipped through the warped cabin window, touching the quilt where both babies slept. She would wake to the sound of the two-year-old padding barefoot across the floor, her small hand brushing her mother’s arm before reaching for the ragdoll. Somewhere outside, the slow scrape of a shovel or the thud of an axe told her he was already working.

It was the children who first broke the invisible wall between them. His daughter, though too small to know the difference, seemed to sense when she was near, fussing until she was placed in her arms. Her own daughter took to shadowing him as he worked, her little fingers tracing the smooth grain of the porch railing, while she peppered him with questions in the only way toddlers could, by pointing and naming things, demanding his agreement. “Horse,” she’d say. “Fence. Hat.” Each word was met with a nod or the faintest smile.

One afternoon, she found the two girls lying side by side on a folded blanket in the yard, their tiny hands touching, their breathing synced. He stood a few feet away, leaning on a post, watching them as if they were the only thing worth seeing. She realized then that his gaze was not the sharp, measuring look of someone deciding if you belonged. It was the quiet regard of a man who had already decided you did.

Meals became shared without discussion. She would cook; he would fetch wood or water. The older girl began handing him spoons and bowls as if she’d always done it. Sometimes he’d set the babies in their cradle side by side while the three of them ate, and she’d catch herself watching him—not for what he was doing, but for how he moved, the way he slowed down near the children, the way his big hands never seemed clumsy when they lifted something fragile.

On the fourth day, she found a pair of small leather shoes on the bed where her daughter slept. The stitching was worn, but careful, the soles patched. She turned them over in her hands, wondering when he’d slipped them there. That evening, the girl wore them to the table, kicking her feet under the bench with pride.

Later, while the fire snapped in the hearth, he sat carving a thin strip of wood, smoothing its edges with the back of his knife. “My father used to make toys for us,” he said quietly, not looking up. “Said a child’s hands should always have something good to hold.” He placed the finished piece on the table—a small wooden horse, simple but solid. The older girl picked it up, tracing its shape with her fingers before pressing it to her chest. Her heart caught at the sight. No one had ever made her daughter something just to make it. No price, no bargain, no debt.

That night, as she nursed both babies in turn, the older girl climbed into his lap with the wooden horse and began to hum. He didn’t move her, didn’t hush her. His gaze met hers across the firelight, and something unspoken passed between them—something that felt like the first plank in a bridge neither of them had planned to build.

But the world beyond the cabin hadn’t gone quiet. On a trip into town for flour, she caught the stares. Two women leaned close to each other outside the mercantile, their eyes flicking from her to the man unloading grain from his wagon. A man at the hitching post spat into the dust, muttering just loud enough, “Strays always find each other.” She kept her chin high, but the words followed her all the way back to the wagon.

He didn’t speak until they’d left the last building behind. “You don’t have to listen to them.”

“I’ve heard worse,” she said.

He glanced at her, then back to the road. “Still shouldn’t have to.”

The cabin felt warmer than usual when they returned, the babies fussing until they were in her arms. She fed them, his gaze steady from the hearth. The older girl handed him the wooden horse before climbing into her mother’s lap, as if making sure he’d keep it safe until morning.

That evening, the two of them sat on the porch while the children slept. The air smelled of pine and cooling earth. He turned the wooden horse over in his hands before setting it on the rail between them.

“I can’t give them everything,” he said, voice low. “But I can give them this—a place no one can take from them.”

She looked at the horse, then at him. “And me?”

His eyes held hers for a long moment, something steady and unfinished in them. “I’m still figuring what I can give you.”

The quiet stretched between them, not uncomfortable, but weighty, the kind that seemed to settle in your bones. Somewhere inside, a baby stirred, and the sound drew them both to their feet. When she reached the cradle, the newborns were sleeping side by side, their small hands clasped in a way neither of them could have arranged. She stood there, watching the rise and fall of their chests until she felt him step up behind her. His voice was barely above a whisper.

“Looks like they already decided for us.”

The days continued, the rhythms of work and care blending their lives together. One evening, as she stirred a pot of stew, he entered carrying wood, his shirt damp at the collar from work, his hands rough but gentle. They ate together, their hands sometimes brushing, the table smaller than it once seemed. After dinner, he leaned back, his gaze steady.

“I’ve been thinking,” he said, “about how this works. About us. I can’t raise these girls halfway. I can’t be just the man who brings food or cuts wood. If you stay, it has to mean something more.”

She swallowed, setting her fork down. “And if I can’t give you more?”

“You already have,” he said. “But I’d ask for your hand all the same.”

The fire popped, startling one of the babies into a soft cry. She rose, rocking the child gently. He watched her, elbows on his knees, hands clasped as if holding himself still.

“I’ve buried one wife,” he continued quietly. “Didn’t think I’d ever speak those words again. But I look at you and it’s not the same as before. It’s not replacing, it’s building something new.”

Her throat tightened. “The town will talk.”

“They already do,” he said. “But they don’t get a seat at this table.”

The two-year-old was humming now, dragging the wooden horse along the table’s edge. The sound was light, unbothered. The baby in her arms sighed and settled again. She looked from one child to the other, then at him.

“You’d have me for my milk,” she said softly.

His jaw tightened, but his voice was steady. “I’d have you because you didn’t turn away. From her, from me.”

Silence folded over them, broken only by the faint hiss of the pot cooling on the stove. The words hung in the air, waiting. She could feel the ground shifting under her feet, dangerous, but steady in a way she hadn’t felt in years. Finally, she nodded once.

“Then ask me properly.”

He rose, crossing to her. He stood close enough that she could smell the faint scent of pine smoke on his shirt. “Will you marry me?”

Her answer was a whisper, but it carried. “Yes.”

Something in his shoulders eased, though he didn’t touch her, as if holding the moment between them without breaking it. The older girl clapped her hands, not knowing why, but sensing something had changed. He gave a short laugh, the first she’d heard from him that wasn’t just air in his chest.

“Then it’s settled,” he said.

They finished the meal with the ease of people who had stepped over a threshold they could never unstep. The children drifted toward sleep, the fire burning low. He washed the bowls while she set the babies in the cradle side by side, their small hands finding each other even in dreams.

When she turned back, he was standing at the table, looking at it as if seeing it for the first time.

“It’s not a mansion,” he said quietly.

“But it’s ours,” she replied, resting her hand lightly on the table’s worn edge.

“Homes aren’t built from walls,” she said. “They’re built from moments like this.”

He looked at her then, not with hunger, not with pity, but with a steady recognition she had first seen in the street. Outside, the wind shifted, carrying the scent of rain that would come by morning. Inside, the cabin held its warmth, the fire’s glow reaching across the floor to touch them both.

It wasn’t the grand moment some might expect—no music, no crowd, no preacher’s voice—just stew on a wooden table, two children dreaming in the corner, and the knowledge that they had chosen each other not out of rescue, but out of recognition.

And as she watched the babies sleeping, her heart finally settled. She had found a home—not in the walls, but in the hands that had offered her a place beside them, for as long as it took.

play video: