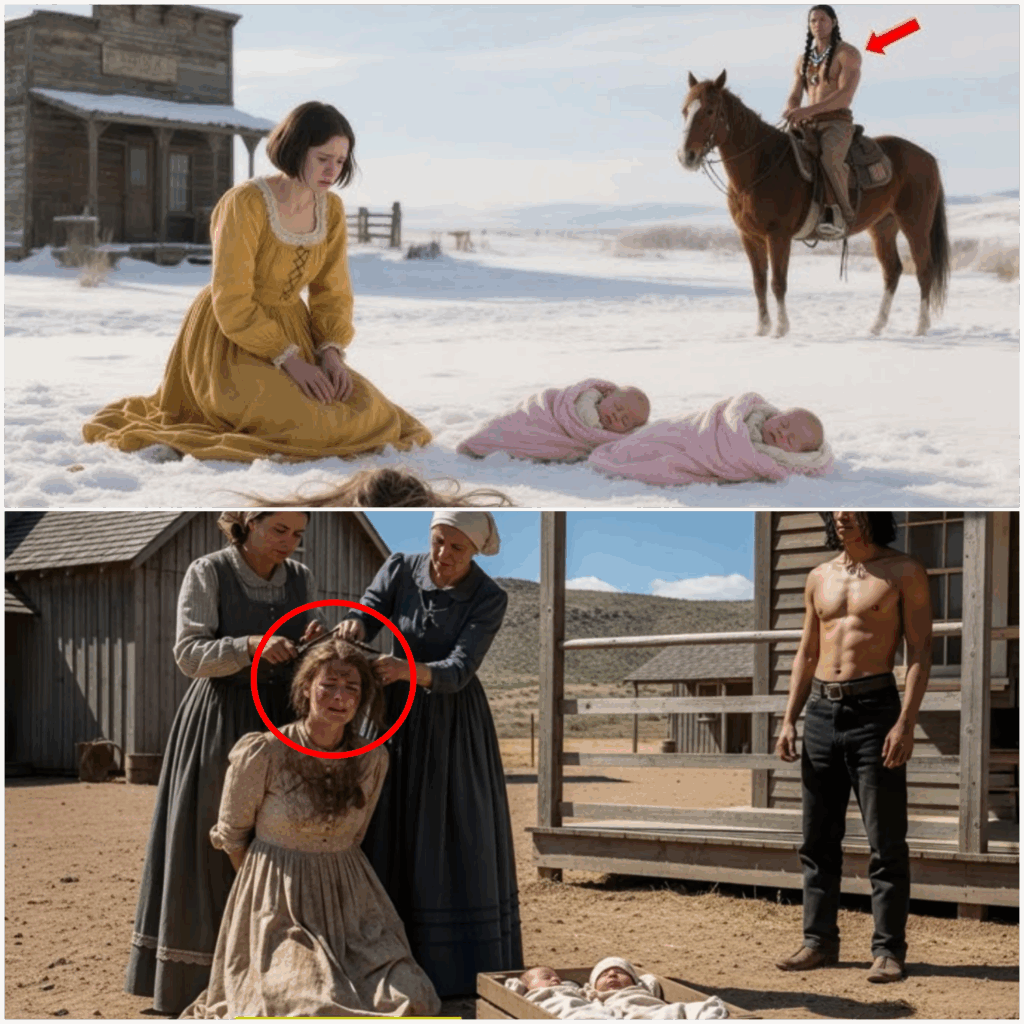

“You’re Coming With Me”, Giant Apache Said After In-Laws Cut Her Hair for Giving Birth to Twin Girls

.

.

.

“You’re Coming With Me”

The wind had a different sound that day—less like weather, more like warning. It carried the scrape of scissors and the thin, uneven cries of newborns, fragile as thread in the vast, empty air. Lisa knelt in the dirt of her in-laws’ yard, her hair twisted in a rough, unforgiving hand, her dress clinging where milk had leaked through. Her bare feet were half-sunk in the dust, the earth cool beneath her toes, but her cheeks burned under the eyes that watched without kindness.

The twins lay in a crate beside her, swaddled in threadbare blankets, their mouths rooting for milk that would not come quick enough. The hand in her hair yanked again, tilting her face toward the sun until her eyes watered.

“For shaming us,” the voice above spat, “for giving him nothing but girls.” The words weren’t new. They had seasoned her days for years, but today they bit deeper, drawn across the fresh wounds of childbirth and loss. The scissors clicked open and shut in rhythm with her heartbeat. Each sound took another piece of what she had left.

The yard smelled of dust, sour milk, and the faint tang of iron. The horizon shimmered in the heat, but the wind, restless and cool, lifted grit into the air, stinging her skin. The voices around her blended into a low, mean hum—until they stopped. Not because mercy had come, but because someone had stepped into the silence.

He stood at the fence line, one hand on the worn wood, the other loose at his side. Bare chest browned by the sun, black hair stirring in the wind, he stood with the stillness of someone who belonged to no one’s schedule but his own. He was tall—the top rail barely reached his hip—his eyes dark and unreadable, fixed on her. No flicker of pity, no smile, just a steady, unblinking gaze that seemed to see beyond the dirt and the hair and the crate of crying girls.

No one spoke at first. They glanced at him, then back to her, as if checking whether she would claim him or deny him. The scissors hesitated midair. That was when he moved—not fast, not slow, but with the inevitability of water finding its way downhill. He stepped through the gate without asking, crossed the yard until he was close enough for her to see the faint white scars crossing his forearms. Without a word, he pried the scissors from her captor’s hand and let them drop into the dust. The metallic ring seemed to hang in the air.

Then he extended his hand to her, palm up, a gesture as simple as it was absolute. “You’re coming with me,” he said. His voice was low and deep, carrying not demand but certainty, like a fact already settled somewhere beyond the reach of this yard.

Her first instinct was to keep her eyes down, to stay small and unnoticed. She had lived on that instinct for years. Her knees pressed into the dirt, and for a moment she thought she might simply stay there, unmoving, until the moment passed and the world closed back over her. Then the twins cried again, sharp and piercing, as if they, too, felt the shift in the air.

He turned toward the crate, crouched, and lifted one baby into the curve of his arm. His large hand nearly spanned her entire swaddled body, yet he held her with a care that made Lisa’s throat tighten. Without looking at her, he tucked the child close to his bare skin. The baby’s small cheek pressed against his shoulder. He glanced back, and in that single measured look, she understood. He wasn’t asking for her trust. He was offering his.

The yard was so quiet she could hear the wind move through the brittle grass at the fence. Her in-laws muttered about savages and shame, but their voices sounded far away now, thin and unanchored. She reached for the other twin, lifting her against her chest. The baby was warm, solid, real—something worth standing for.

He stepped back, making space for her to rise. Her legs trembled from childbirth and weeks of half-meals, but she got to her feet. No one stopped her. Perhaps it was the weight of his presence. Or perhaps they had already decided she was no longer worth keeping. They walked out through the gate together. His stride was long, unhurried. She matched it as best she could, clutching her child and feeling the grit grind into the cuts on her soles. No one followed. No one dared.

The road stretched ahead in pale dust, the sun sinking lower, staining the horizon in copper. She glanced sideways once, curious despite herself. He didn’t look at her, but at the space ahead, as though measuring the distance to something she could not yet see. They reached the crest of a small rise, and there the wind shifted, warmer now, bringing the scent of pine from somewhere far off. Below lay the valley, low hills softened by late light, a dark ribbon of trees marking a creek. She had not been beyond the town’s edge in months. The openness made her feel both exposed and free.

For a time, the only sounds were the creak of his steps on the dirt and the soft wet breaths of the twins. She wanted to ask where they were going, why he had come, if he expected something of her, but each question caught on the edge of her tongue, tangled with the knowledge that she was already past the point of turning back.

They stopped beside a wagon hidden under a wind-bent cottonwood. It wasn’t much—one wheel patched with rawhide, the bench worn smooth, but the harness was oiled and the horse sturdy. He set the twin gently into her lap as she sat, then took up the reins without a word. The horse started forward at a slow, steady walk.

The road wound between low hills, shadows lengthening. She could feel the day cooling against her skin, could hear the faint sigh of the babies settling into sleep. Her hands, stiff from holding them too long, began to relax.

The rhythm of the wagon lulled her, but she stayed awake, watching his profile in the dimming light. There was a stillness in him that wasn’t emptiness. It was the stillness of someone who carried his own weather, who would not be bent by the wind. The sky turned from copper to indigo. Stars began to show above the hills. Somewhere in the darkness, a coyote called, its cry rising and falling like a thread pulled taut. The sound made her tighten her hold on the twins. He glanced at her then, the faintest flicker of a look, and she realized it wasn’t reassurance he was offering. It was acknowledgment.

They rode on, the road narrowing until trees closed in on both sides. The scent of pine grew sharper, mixing with the faint sweetness of wood smoke. Somewhere ahead, a light glowed warm and steady, spilling out into the night. She could feel her pulse in her throat, the tired ache of her body giving way to something sharper—a recognition that she was crossing a threshold she didn’t yet understand.

The horse slowed as they approached the source of the light. Through the trees, she saw a cabin, smoke curling from its chimney, its door standing open as if waiting. He drew the wagon to a stop and set the reins aside. For a long moment, he didn’t move, just sat there in the cooling air, the night holding its breath around them. Then he climbed down, came around to her side, and held out his hand again. Same gesture, same unspoken weight as in the yard. This time she didn’t hesitate.

When her bare feet touched the packed earth, the warmth from the open door reached her. The twins stirred, one giving a small cry before settling. She looked past him into the cabin’s dim interior, where shadows moved against the firelight. And just as she stepped forward, the wind rose again, carrying with it the faint echo of hoofbeats somewhere behind them.

Snow had begun to fall by the time they reached the cabin. Soft, tentative flakes that melted as soon as they touched the wagon boards. The light from inside spilled onto the ground in a warm rectangle, cutting through the blue shadows of the pines. Lisa hesitated at the doorway, the twins heavy against her chest, unsure whether she was stepping into shelter or into another set of walls she would have to learn her way around.

He didn’t speak. He stepped past her, crossing the room with the quiet assurance of someone who belonged there. The fire on the stone hearth crackled low, its heat thick with the smell of pine resin. Against one wall, a cradle sat waiting, its wood polished smooth by years of hands. It seemed too deliberate to be a coincidence, and she wondered who had once slept there, and why it had been kept.

He took the twin from her arms, laying the baby gently into the cradle, then motioned for her to follow him to the table. A loaf of bread, dark-rusted and fragrant, sat beside a slab of venison and a tin cup of milk. He pulled out a chair. She lowered herself into it slowly, the stiffness in her body reminding her of every mile of the day. She ate in silence, her eyes flicking to him now and again. He moved with an economy that came from long habit, refilling the fire, setting a kettle to boil, checking the latch on the shutters. She couldn’t decide if his quiet was a barrier or a kindness.

Later, when she rose to tend the babies, she found the cradle’s mattress soft and freshly lined. One twin stirred, opening her tiny mouth in a mewling cry. Lisa gathered her up, swaying on her feet as she nursed. The baby’s small hand found the edge of her dress, curling in the fabric. For the first time in days, Lisa felt something inside her unclench.

The hours after the children fell asleep stretched long. She sat on the edge of the bed he had pointed her toward, listening to the cabin settle—rafters creaking, embers shifting in the grate. Somewhere near the door, she heard the faint sound of movement. She rose, padding softly across the room, and found him seated by the entrance, rifle across his lap, eyes on the night. He turned his head slightly when he noticed her, but said nothing. She wanted to ask if he always kept watch or if he expected trouble tonight. Instead, she went back to bed, the image of him in the dim light fixed in her mind.

The next morning, she tried to sweep the floor with a broom she found in the corner. He returned from bringing in wood, said nothing. But when she came back from hanging the wash, she found a folded dress on the bed. Plain calico, but whole and clean. It smelled faintly of cedar. She ran her fingers over the seams, wondering whose hands had stitched them.

By afternoon, the weather had shifted. A low mist crept between the trees, and the cold settled deep enough that her breath showed in faint clouds. She stayed inside with the twins, mending one of their blankets with thread from a jar on the shelf. Now and then, she heard the thud of his boots on the porch, or the sharp ring of an axe splitting wood.

On the second day, a lone rider passed by, slowing as he spotted her on the porch with the babies. His eyes lingered too long, his smirk curling at the edges like paper in a flame. She felt the hot press of shame rise to her cheeks. When she glanced toward the yard, she saw the Apache man watching from the corner of the cabin, his stance easy, but his gaze hard as stone. The rider clicked his tongue at the horse and moved on.

That night, she found herself staring into the fire long after the twins had fallen asleep, thinking about the way the man’s presence had silenced that smirk. She didn’t know if it was gratitude she felt, or something quieter, more unsettling.

By the third day, a rhythm began to take shape. He would leave before dawn, returning with wood, game, or sometimes nothing at all. She would tend the children, cook what little they had, and try to ignore the strange blend of safety and uncertainty that clung to her in this place.

One evening, she hummed a lullaby her mother had once sung. Her voice was low, worn from disuse, but the babies quieted under it. She didn’t hear him come in, but when she looked up, he was standing in the doorway, leaning one shoulder against the frame. He didn’t speak, didn’t cross the threshold, just stood there until the song ended. Then he turned away, his shadow slipping into the firelight before the door clicked shut.

The days stayed cold, the nights colder still. Once she woke to find a heavy quilt pulled over her and the babies, though she had fallen asleep without it. The cabin smelled of smoke and something faintly sweet—wild sage, maybe, caught in the folds of the fabric.

On the fifth day, the sound of hoofbeats broke the quiet. She stepped to the window and saw two figures riding past, their eyes flicking toward the cabin. They didn’t slow, but the tilt of their heads told her they’d seen what they came to see. Gossip was like wildfire. It only needed a spark.

That evening, he came in with snow in his hair. He shook it off by the door, then set a rabbit on the table. She met his eyes for the briefest moment, long enough to catch a flicker of something there. Not curiosity, not caution, but the quiet calculation of a man who weighed each thing before deciding its place. They ate by lamplight, the twins bundled in their cradle, the fire casting slow shadows up the walls. When the last of the bread was gone, he reached into a drawer, took out a length of thin leather, and handed it to her.

“For them,” he said simply. She turned it over in her hands. It was a cord, braided and strong, with a tiny shell threaded into the weave. She didn’t ask what it meant. Some things were better learned in their own time.

That night, the wind picked up, rattling the shutters. She lay awake, listening to the branches scrape the roof, and thought of the two riders, the smirking stranger, the whispers that had already begun in her absence from town. She rose quietly, crossing the room to check the latch on the door. He was there already, standing in the dark, looking out into the trees. His face was turned toward the black beyond the porch, but his voice when it came was low and certain.

“They’ll be looking this way soon.” He didn’t glance at her. Didn’t soften the words. But he didn’t move aside either. And in the narrow space between his stillness and the door, she felt the first tremor of understanding. Whatever storm was coming, he meant to meet it head-on.

Somewhere in the distance, beneath the howl of the wind, the faint sound of hooves echoed again, closer.

This time the frost came overnight, laying its thin white skin over every fence post and pine branch. Breath rose from the horse in slow clouds as he hitched it to the wagon. Lisa stood at the doorway with the twins bundled against her chest, the cold nipping through her shawl. He glanced up once, gave a short nod toward the wagon bed, and she climbed in without question.

The road to town was rutted from the freeze-thaw, the wheels jolting over each ridge. The twins slept despite the motion, their small faces pressed together under the quilt. He drove with one hand, the other resting on his thigh, eyes fixed ahead. She studied the dark line of his jaw, the way the early light caught in his hair. It wasn’t beauty that held her attention, but the sense that he moved in rhythm with something older than the road beneath them.

Town came into view slow, like a picture forming from the fog. Smoke from chimneys, the faint clang of a blacksmith’s hammer, the murmur of morning voices. As the wagon rolled down the main street, the voices quieted, replaced by the unmistakable prickle of eyes turning to follow. She felt it instantly, that old familiar weight. The judgment here was sharper, dressed not in open cruelty, but in the sideways glance, the lingering stare, the tight-lipped whisper passed from mouth to ear.

Women with baskets paused midstep. Men leaning on posts straightened, their gazes sliding between her and the man at the reins. They stopped outside the general store. He climbed down first, then reached for the twins. She hesitated, the old reflex to keep them close pulling at her, but his hands were steady, palms open. She let him take them, her arms feeling too light as she stepped to the ground.

Inside, the warmth smelled of flour and lamp oil. She gathered what they needed—flour, beans, a bit of salt, pork—aware of the storekeeper’s eyes darting between her and the window where the Apache stood with the twins. His presence there drew stares like a magnet, though he seemed not to notice. Or maybe he noticed everything and simply refused to bend to it.

When she stepped back out, a man by the hitching rail gave a slow, crooked smile. “Didn’t know you took in strays?” he said, loud enough for others to hear. The words landed sharp, dressed as jest, but heavy with insult. She froze, her pulse in her ears. Before she could answer, the Apache shifted the twins in his arms and took a single step forward. He didn’t raise his voice or curse, but the space between him and the man grew heavy, dense as a storm about to break. The man looked away first, muttering as he turned back to his horse.

They left town without another word. The rhythm of the wagon wheels was the only sound until the buildings were far behind. She wanted to thank him, but the words felt too thin. Instead, she adjusted the quilt around the twins, making sure their faces were warm. The land opened wide again—low hills brushed with frost, the creek running black between its banks. She realized somewhere along that road that his silence wasn’t distance. It was steadiness, the kind that kept you from falling, even when the ground under you shifted.

Back at the cabin, the twins were fussing, and she busied herself with feeding them while he unloaded the supplies. When the girls finally slept, she found him outside mending the fence. The air smelled of cedar and cold earth. She stood a moment, watching the ease of his movements, the patience, and the way he threaded the wire. He didn’t look up, but she knew he was aware of her.

That night, the fire burned low. She hummed again, the same lullaby as before. And this time, when she glanced up, he was closer, leaning against the table, eyes on the cradle. The babies’ fists flexed in sleep, their breathing soft.

“They look like you,” he said quietly, as if testing the sound of the words. It was the first thing he had said to her that wasn’t about direction or necessity. She didn’t know how to answer, so she just nodded.

The days began to carry a shape. Mornings for work—him with the wood and repairs, her with the washing and the children. Afternoons sometimes brought visitors, though never inside. Neighbors with curious eyes, riders passing slow along the road. The watching never stopped. It pressed in even here, a reminder that the world beyond the cabin hadn’t forgotten.

One afternoon, she sat on the porch, rocking one of the twins, when a small group of women passed along the fence line. Their voices were low, but the winter air carried every word. “Poor thing,” one murmured. “Poor nothing! She’s made her bed with him! Lord, help those babies!” She kept her eyes on the horizon until they were gone, then went inside, her chest tight.

He was by the fire carving something from a block of wood. She didn’t tell him what they’d said. She didn’t need to. That evening, as the sun bled into the hills, he set the carving on the table. A small horse, rough but careful. One of the twins reached for it with a clumsy hand, and he let her hold it. The child gnawed on the ear, drooling down the side, and he only smiled faintly before setting it back on the table.

Later, as she banked the fire, she realized the little horse was more than a toy. It was a marker, something made here in this place for them. But the watching eyes didn’t fade. If anything, they grew more intent.

On the seventh day after their trip to town, she woke to find boot tracks in the snow outside the porch. They didn’t lead to the door, just stopped halfway, then turned back toward the road. He saw them, too. His gaze lingered on the prints, the muscle in his jaw tightening.

When she asked if it was trouble, he only said, “Not yet.”

The next afternoon, they went to fetch water from the creek. The twins were bundled in the wagon, their breath making little clouds. She walked ahead, the rope of the bucket cold in her hands. The creek was running clear despite the ice on its edges, the sound of it low and steady. She knelt to fill the bucket. And when she straightened, she saw them. Two men on horseback, half hidden by the trees. They didn’t speak. They didn’t need to. Their eyes on her were enough to make her grip the bucket harder. The Apache stepped between her and the tree line. His body an unspoken wall. After a moment, the riders turned and disappeared into the shadows.

Back at the cabin, she fed the twins while he stacked the wood pile higher. Neither of them spoke of what had happened. But when night came, she noticed he didn’t sit inside by the fire. Instead, he stood outside under the stars, his breath rising in the cold, watching the road.

She lay in bed, the twins warm against her, and thought about the way those riders had looked at her. Calculated, certain. It wasn’t gossip anymore. It was intent. And somewhere beyond the dark pines, hoofbeats moved again, slow and measured, as if the night itself had eyes trained on the cabin.

Snow fell without hurry, drifting from a sky the color of pewter. By morning, the fence posts were capped in white, and the world seemed hushed, as if the land itself had drawn a blanket over its shoulders. Inside the cabin, the fire snapped, its warmth carrying the faint scent of pine pitch. Lisa sat at the table, the twins in her lap, their small fingers curling into the wool of her shawl. Across the room he knelt by the hearth, feeding in another split log.

Winter had a way of slowing everything. And yet the days felt taut, as if stretched over some waiting point neither of them would name. They worked side by side without speaking much, drying meat by the fire, mending clothes, stacking kindling within easy reach. The rhythm was steady, almost gentle, but beneath it lay an unspoken watchfulness.

One afternoon, as flakes thickened and the wind took on a sharper edge, he showed her how to bank the fire so it wouldn’t die in the night. His hands were steady on the poker, the metal ringing softly against the stones. She watched him, noting how his touch was precise but unhurried, as though fire itself trusted him. When she tried, her movements were clumsy, the embers collapsing too soon. He said nothing, only shifted the coal with a quick flick and let her try again. By the third time, the glow held.

Later, they sat by the window with tin cups of coffee. The twins slept, their breaths rising and falling in the cradle. She told him their names, softly, as though the snow outside might carry the sound away. He repeated them, low and deliberate, as if learning a piece of terrain he meant to keep. Something inside her loosened at the sound, though she kept her eyes on the snow.

But the stillness didn’t last. News came from the road. A peddler stopping to trade salt for dried venison brought it with him. Her in-laws were angry, saying she had stolen the twins and run off with a savage. The word had traveled through three settlements already. She felt her stomach tighten, the coffee in her hands suddenly too bitter.

That night, she paced the cabin after the twins had been put down. Her thoughts tangled. If they came, could she stand in front of them and hold her ground? She wasn’t sure. Years of being told she was nothing had left grooves deep enough to fall into without trying. He sat at the table, a wet stone in his hand, drawing the blade of his knife against it in slow, even strokes. The sound was steady, almost calming.

“They won’t take what’s yours,” he said at last.

She stopped pacing, the words settling over her like the first weight of a quilt. He hadn’t said our, he’d said yours. The difference mattered more than she could explain.

In the days that followed, the snow deepened, muffling the world to the edge of the porch. She spent the hours rocking the twins, sewing a crude cloth doll from scrap fabric. When she finished, she set it on the hearth to dry. That evening she found it on the mantle, centered between a small clay pot and a strip of beadwork. He didn’t mention moving it, but she knew his hand had done it.

Outside the air sharpened. On the fourth night, hoofbeats carried faintly through the snow, far off but deliberate. He set down the leather he’d been braiding and stood, taking his coat from the peg.

“Stay in,” he said, and stepped into the white dark.

She stood at the window, the glass cold under her palm, and watched his shape move through the falling snow. He didn’t hurry. The flakes caught in his hair, on his coat, blurring the lines of him until he looked carved from the night itself. Somewhere beyond the trees, the hoofbeats stopped. Minutes stretched. The twins stirred, one letting out a short cry before settling again. She kept her gaze on the edge of the woods, breath fogging the glass.

At last, his figure reappeared, walking back toward the cabin. He didn’t bring word of who had been there. He didn’t need to.

The next day, the wind shifted, bringing with it the smell of woodsmoke not their own. She noticed him checking the rifle more often, stacking more wood inside. When she asked if someone was close, he only gave a short nod.

The snow kept falling. At night, the cabin felt like the center of a small, fragile world—the cradle’s soft creak, the hiss of the fire, his shadow moving across the walls. She found herself measuring time not by the clock, but by these small repetitions.

One evening, she came in from shaking the snow off the blankets and found him by the hearth with one of the twins in his arms. The baby’s tiny hand was tangled in his hair, and he was rocking just enough to keep her quiet. Lisa stood in the doorway a moment, unseen, and felt something she hadn’t in years—a sense that maybe she belonged somewhere, not as a guest, not as a burden, but as part of the frame.

That night, as she lay in bed, she could hear the wind scouring the cabin walls, trying its best to find a way in. He was outside again, his boots crunching softly over the snow, each step measured. She thought of the in-laws, of the riders by the creek, of the eyes that had followed them in town. The wind might wear itself out, but the people behind those eyes would not.

By morning, the snow lay deep enough to cover the lower rails of the fence. The air was so still it felt like even the trees were listening. He stood at the window, looking out, his hand resting lightly on the rifle leaning against the wall. She joined him there, the twins warm against her.

“What happens if they come?” she asked.

He looked at her and for a moment his gaze was almost soft. “Then we keep what’s ours.” It was the first time he’d said we. The word landed in her chest like a small fire catching hold. She nodded and together they watched the snow drift down, each flake falling as if it knew exactly where it meant to land.

But when dusk came, so did the sound. Dull, rhythmic, traveling through the frozen ground—hoofbeats again, closer than before. No longer hesitant, she could feel them in her bones, in the way the twins shifted restlessly against her. He reached for his coat, pulled it on without haste. At the door, he paused, looking back at her for the briefest moment, and there was something in his eyes—not warning, not fear, but a promise.

Then he stepped out into the falling dark, leaving the door open just long enough for the cold to slide across the floorboards and remind her that the snow between them was no longer just winter. It was the thin edge of what would come next.

The night came heavy, pressing against the windows with the weight of the storm and the world beyond it. Snow fell in relentless silence, muffling the trees, swallowing the sound of the creek. Inside the cabin, the fire burned low, the embers pulsing with a slow red breath. Lisa held the twins close, feeling their warmth against her chest, her ears tuned to every sound beyond the door. He had been gone only minutes, but each one felt longer than the last.

She could still see the shape of him in her mind, dark against the falling white, moving with that same measured certainty he carried in every step. She listened for voices, for hoofbeats, for anything that might tell her what waited in the snow.

When the door opened, the cold came first, sharp and metallic in her lungs. He stepped inside, shoulders dusted with flakes, his breath curling in the air. His eyes swept the room, lingering on the twins, then on her.

“They’re here,” he said simply.

Her heart beat once, hard, as if the sound itself could crack her ribs. She stood, placing the twins in the cradle, tucking the quilt tight around them. Her hands shook, but not from the cold. The hoofbeats came next, slow, deliberate, drawing up to the edge of the yard. Through the window, the shapes of three riders emerged from the snow, their forms blurred but their intent clear. Her in-laws. She knew the curve of the lead rider’s shoulders, the tilt of his head, even before he called her name.

“Come out!” he shouted, his voice flat in the cold air. “Bring the babies. This is done.”

She looked at him, her unlikely protector, and found no trace of hesitation in his face. He stepped to the door, opened it, and stood in the frame. The wind pressed against him, snow swirling at his feet.

“She’s not leaving,” he said, his voice low but carrying. It wasn’t a challenge. It was a fact, laid down like the stones of a foundation.

A scoff from the yard. “They’re ours. She’s nothing. You think we’ll let her?”

He stepped forward, closing the space between the doorway and the snow. “They’re hers,” he said. “And she stays.”

Lisa’s breath caught. The words were a wall and he stood inside them with her. One of the riders shifted in his saddle, glancing toward the others. Snow hissed softly against their coats. The lead rider leaned forward, his mouth twisting into something between a sneer and a smile.

“You don’t get to decide.”

“I already did,” the Apache replied.

The stillness that followed was heavier than shouting. Snow gathered on the brim of their hats, in the folds of their scarves. Lisa could hear the twins breathing in the cradle, the fire crackling behind her. Every sound seemed too loud.

Her in-laws dismounted, their boots crunching in the snow. The cold pushed in through the open door, carrying the smell of leather and old anger. Lisa’s body went rigid, her hands curling into fists she didn’t remember making. She had faced them so many times before—head down, voice small. But now the doorway was filled with someone who would not step aside.

The lead man took one step closer. “You’ll regret this,” he said. But the words felt brittle, like they might break in his mouth.

“I don’t think so,” the Apache answered. And there was something in his tone—not threat, not even defiance, but a deep certainty that made the air itself seem to lean toward him.

Lisa felt the moment shift. The power her in-laws had held for years was not here, not in this yard, not under this sky. They stood there a beat longer, then turned without a word, mounting their horses. Snow swallowed the sound of their retreat, leaving only the hiss of the wind through the pines.

When he came back inside, he shut the door gently, as though the night might still be listening. She stood where she was, her pulse still high, her breath unsteady. He set his coat on the peg and looked at her—not with triumph, but with a quiet that seemed to see straight through her.

“You should eat,” he said, as if it were the most natural thing in the world to speak of food after such a moment. But she shook her head. Her voice came before she could stop it. “I’ve never told them no before.”

His gaze didn’t waver. “You just did.”

Something inside her, something small and long buried, shifted at that. She crossed to the cradle, brushing a hand over the twins’ cheeks, feeling the warmth of them against her cold fingers. She had stood her ground—not alone, but still standing.

He moved about the cabin, laying another log on the fire, setting bread and stew on the table. The light from the flames caught on the edge of his jaw, the curve of his hands as he worked. There was no celebration in his movements, only the steady continuation of what needed doing.

When they sat to eat, the twins stirred, one letting out a soft cry. Lisa rose to take her, but he was already there, lifting the baby with a care that belied his size. He cradled her in one arm, spooned stew with the other. Lisa watched the way the baby’s hand curled around his finger, the small sounds she made settling against him.

Later, when the fire had burned low and the snow pressed close against the windows, he took something from his pocket—a small bracelet braided from thin strips of leather with a bead of bone threaded at the center. He set it on the table between them.

“For them,” he said.

Her fingers closed around it before she could think. It was too small for the twins, and when she slipped it onto her own wrist, it fit as if it had always been meant for her. He didn’t correct her.

They sat there a long while, the bracelet warm against her skin, the cabin filled with the slow breathing of the twins and the soft pop of embers. The world outside was still, the snow falling in a steady veil, but inside something felt anchored for the first time in years.

When she finally rose to bank the fire, she found herself looking at him—not with the guarded curiosity she’d carried since the day he’d taken her from the yard, but with a recognition she couldn’t yet name. He had not promised her safety with words. He had lived it, without condition.

As she lay in bed, the twins curled against her, she listened to his boots move across the floor. The soft creak of the chair by the door as he settled in. Outside, the snow kept falling, covering the tracks of the riders until the night held no sign of them at all. And she knew with a certainty as deep as the cold in the ground that whatever roads lay ahead, however many eyes might watch, however many storms might come, she would not walk them alone.

The firelight flickered across the walls, and in the cradle of that warmth, she closed her eyes. The last thing she heard before sleep was the steady rhythm of his breathing by the door.

End of Story

play video: