His Logging Trucks Kept BREAKING, so he Built His Own… and Changed Trucking Forever

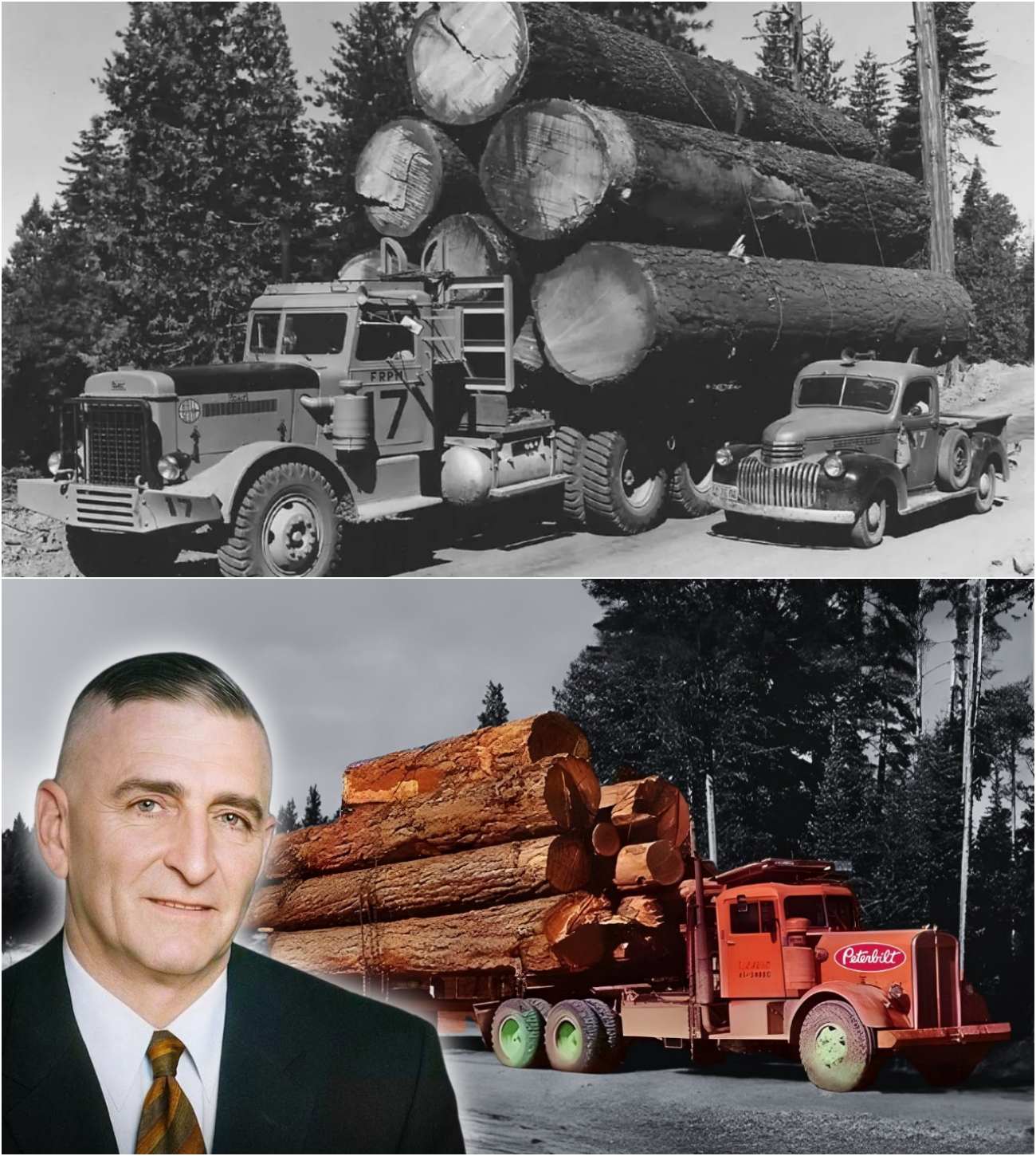

The Pacific Northwest, 1938. Picture this: the rain poured down in sheets, a typical day in this lush, green paradise. Amidst the towering trees and the sound of rushing water, a man named Theodore Alfred Peterman stood in a logging camp, fuming—not at the weather, but at his trucks. Peterman was not a trucker; he was a plywood magnate, owning mills up and down the West Coast. His entire operation depended on moving massive logs from the forests to his mills.

But the trucks kept breaking. Not occasionally—constantly. Peterman had purchased the best trucks money could buy in the 1930s, but it didn’t matter. They cracked frames on mountain roads, blew transmissions hauling loads up steep grades, and broke axles on rutted logging paths. Each time a truck went down, logs sat in the forest, mills sat idle, and money burned.

Most businessmen in Peterman’s position would have accepted their fate, perhaps complaining to the manufacturer or negotiating better warranty terms. But not Peterman. He looked at those broken trucks and thought, “I could build better.”

A Visionary with No Engineering Background

Here’s the kicker: Peterman wasn’t an engineer or a mechanic. He was a businessman who processed wood. Yet, he understood something fundamental about the logging industry that the big truck manufacturers in Detroit didn’t: these weren’t highway trucks. They weren’t delivery vehicles. They were combat machines, fighting mud, mountains, and the laws of physics every single day. They needed to be built differently—stronger, tougher, more purpose-built.

In late 1938, Peterman heard that a small truck manufacturer in Oakland, California, was going under—a company called Fagel Motors. Established in 1916, Fagel had built some decent trucks and even pioneered innovations in the 1920s. But by the late 1930s, they were bleeding money, struggling to compete with the giants of the industry. Peterman saw an opportunity.

He traveled to Oakland, walked through the Fagel factory, and looked at their equipment, designs, and workforce. In January 1939, he wrote a check, buying the entire operation—every machine, every patent, and every skilled worker who wanted to stay. But he didn’t keep the Fagel name. No, he created something new, combining his own name with his vision: Peterbilt.

The First Peterbilt Truck

The first Peterbilt truck rolled out in 1939, and it was unlike anything else on the market. Peterman had his engineers build it specifically for logging. They reinforced the frame rails at stress points, added stronger springs, bigger axles, and beefier transmissions—everything designed to survive conditions that would destroy ordinary trucks.

What separated Peterbilt from the start was customization. Most truck manufacturers in the 1930s built standard trucks on assembly lines—one-size-fits-all. Peterman took the opposite approach. He met with loggers, mine operators, and construction contractors, asking them exactly what they needed and then building it. Custom wheelbases, custom axle configurations—custom everything.

This sounds expensive, right? It was. Peterbilt trucks cost more than Mack, more than White, more than anyone. But Peterman’s customers didn’t care about upfront costs; they cared about downtime. Peterbilt trucks kept running. Word spread quickly in the logging industry. These trucks could withstand punishment that killed everything else.

Rapid Growth and the War Effort

By 1940, Peterbilt was building about a hundred trucks a year—all heavy-duty, all custom-spec, all headed to the toughest jobs in the West. Then came December 7, 1941—Pearl Harbor. Everything changed. The military needed trucks—thousands of them—to survive conditions that made logging roads look like paved highways: Pacific jungles, North African deserts, and European mud.

The War Department started placing massive orders with truck manufacturers nationwide. Peterbilt was tiny compared to companies like General Motors or Mack. They couldn’t build thousands of trucks, but they could build trucks that wouldn’t quit. The military noticed. Peterbilt received contracts for specialized heavy haulers, tank retrievers, and logging trucks for timber needed for military construction.

The war years taught Peterbilt something crucial: volume production methods. Building a hundred custom trucks a year was one thing; building military contracts on deadline was another. They had to systematize and standardize certain components, creating parts that could be manufactured faster without sacrificing durability.

Post-War Expansion

By 1945, when the war ended, Peterbilt had evolved. They maintained their reputation for toughness but now had manufacturing efficiency. The post-war construction boom hit—highways were being built, dams constructed, and infrastructure developed everywhere, all requiring heavy trucks. Peterbilt expanded, acquiring new factory space, hiring more workers, and improving equipment.

They began building trucks for more than just logging—dump trucks, heavy haulers, long-distance freight rigs. Each one was still built tougher than necessary because that was the Peterbilt way. But by the early 1950s, Peterbilt faced a good problem: too many orders and not enough factory space.

The Oakland facility Peterman had bought from Fagel in 1939 wasn’t big enough anymore. There was another issue: money. Building heavy-duty custom trucks required capital—lots of it. Peterman had built the company on his plywood fortune, but expanding to meet demand meant serious investment, more than one man could reasonably handle.

Then came 1958. A Seattle-based company called Paccar, Pacific Car and Foundry Company, came calling. Paccar was already big in the truck business, owning Kenworth, another West Coast truck builder with a solid reputation. But Kenworth and Peterbilt weren’t really competitors. Kenworth focused more on long-haul trucks, while Peterbilt dominated the heavy-duty vocational market—logging, construction, mining.

A Strategic Acquisition

Paccar saw synergy. They believed they could let Peterbilt and Kenworth operate independently while sharing some components to save costs. The acquisition happened, and remarkably, it worked. Paccar didn’t destroy Peterbilt’s culture or force them to dilute their quality to hit cost targets. They gave them resources and let them build trucks the Peterbilt way.

Through the 1960s, Peterbilt grew steadily. They introduced the Model 351 in 1954—a conventional cab available in multiple wheelbase configurations, powered by Cummins or Caterpillar diesel engines, becoming the workhorse of the construction industry. You’d see 351s on every major job site in America, hauling dirt, pulling lowboys loaded with bulldozers, and mixing concrete.

But the real revolution came in 1967 with the Model 359. This truck changed everything. It was Peterbilt’s first real long-hood conventional, designed for both work and highway hauling. With a long fiberglass hood and a distinctive grill, it was available with the biggest engines on the market—400 horsepower, 500 horsepower, and more.

A New Era of Trucking

The 359 was special. It looked tough—intimidating and aggressive. The long hood gave it presence, and that vertical grill said serious business. Chrome adorned every surface. This wasn’t just a plain work truck; it was a statement. Owner-operators fell in love with it. By the late 1960s, the trucking industry was changing. More independent drivers were owning their own rigs, and these drivers didn’t just want reliable trucks; they wanted trucks that represented them.

The 359 delivered that. Peterbilt sold thousands of them, offering insane customization. Want a longer hood? Done. Bigger sleeper? No problem. Different axle configuration? Absolutely. Chrome packages as much as you want. The 359 became rolling art for drivers who loved their equipment.

Through the 1970s, the 359 dominated. You’d see them everywhere—cattle haulers in Texas, loggers in Oregon, grain haulers in Kansas, and increasingly long-haul freight operators who wanted durability and style. The 359 became part of American truck culture, featured in movies and TV shows.

Challenges Ahead

But all wasn’t perfect in Peterbilt land. The 1970s brought challenges: fuel crises, emissions regulations, and economic recession. Trucks needed to be more fuel-efficient, and engines had to meet new EPA standards. Customers became price-conscious in ways they hadn’t been before.

Peterbilt responded by developing the Model 362—a shorter hood, more aerodynamic, lighter, and better fuel economy. It was a good truck that sold well, but it wasn’t a 359. It didn’t have that presence and swagger. Through the 1980s, trucking became more competitive. Freightliner pushed aggressively with aerodynamic designs, and International innovated in fuel efficiency.

Peterbilt’s parent company, Paccar, owned Kenworth too. Internal rivalry began brewing—not hostile, but competitive. Kenworth engineers would develop something, and Peterbilt would develop their own version. Sometimes they’d share components to save costs, but each brand fiercely protected its identity.

A Bold Move

In 1987, Peterbilt made a bold move, completely redesigning the 359 and launching the Model 379. Opinions varied; some loved it, while others felt it lost the 359’s character. But the 379 sold because underneath the styling debates, it was still a Peterbilt—tough frame, solid components, built to last.

As the economy recovered, Peterbilt couldn’t build them fast enough. The 1990s saw Peterbilt expanding their lineup with the Model 375, the 378, and the 380, each targeting different segments—vocational, long-haul, regional, day cab, and sleeper. They were becoming a full-line manufacturer while maintaining their reputation for durability.

Moving into the 2000s, Peterbilt faced a different trucking world. Emissions regulations became brutal. EPA mandates required cleaner diesel engines. Each deadline brought new engine technology that manufacturers had to integrate, and it wasn’t simple bolt-on stuff. These new engines affected everything—fuel economy, reliability, maintenance costs, and driver experience.

Navigating New Challenges

Peterbilt, like every truck manufacturer, struggled with the transition. The first generation of emissions-compliant engines was problematic. EGR systems (exhaust gas recirculation) sounded good on paper, but in practice, early systems had issues—sensors failing, coolers clogging, regen problems. Owner-operators who had run Peterbilts for decades were frustrated.

These trucks that had always been bulletproof suddenly had new failure points. But here’s where Peterbilt’s reputation saved them. The engine problems weren’t really Peterbilt’s fault; they were industry-wide. Every manufacturer using these EPA-mandated designs faced similar headaches. But Peterbilt customers stuck with them because the rest of the truck—the frame, the suspension, the components—remained solid.

In 2007, Peterbilt launched the Model 389. This was strategic; the 379 had been successful, but some customers missed the classic long hood look. The 389 brought it back—a big hood, vertical grill, chrome everywhere. It was deliberately old-school in the best way for owner-operators who wanted a truck that looked like trucks used to look.

Maintaining Identity

But keeping two different platform conventional trucks in production was expensive. Tooling costs, inventory complexity, and engineering resources were split between platforms. Remember, Kenworth was doing the same thing. They had their classic and modern models. Paccar was essentially funding duplicate development across both brands.

Through the 2010s, Peterbilt continued refining their lineup. The Model 579, introduced in 2010, was Peterbilt’s first truly modern aerodynamic highway truck—sloped hood, integrated bumper, carefully shaped mirrors and fairings, all designed in wind tunnels to reduce drag. The 579 delivered 10 to 15% better fuel economy than the 387 it replaced. Over a year, over 100,000 miles, that added up to real money saved.

But launching the 579 meant taking a risk. Peterbilt’s image was tough, traditional, classic. The 579 looked futuristic, smooth, and rounded. Would Peterbilt customers accept it? Would they see it as progress or betrayal? The market answered. Fleet customers loved it. Fuel economy sold. Big trucking companies began replacing their aging conventional trucks with 579s.

A Balancing Act

Owner-operators remained more divided. Some embraced the modern design, while others stuck with 389s because that was what a Peterbilt should look like. Peterbilt kept building both because that’s what they did—customization options. You want old school? Here’s a 389. You want modern efficiency? Here’s a 579.

But the challenge remained: how to maintain their identity while adapting to reality. Electric trucks were coming. Autonomous technology was developing. Hydrogen fuel cells were being tested. The next 20 years would transform trucking more than the last 50.

Peterbilt is developing electric models—the 520 and 579 electric variants—but selling electric trucks to customers who’ve run Cummins diesels for 40 years won’t be easy.

A Legacy of Toughness

So here we are, 85 years after T.A. Peterman got frustrated with broken trucks and decided to build his own. Peterbilt is still here, still building trucks in Denton, Texas, where they moved their main production in 2000. They’re still maintaining their reputation, still competing, still mattering.

In an industry that has destroyed countless manufacturers, where names like Fagel, Diamond T, and Brockway have disappeared, survival alone is victory. But Peterbilt has done more than survive; they’ve thrived. They’ve influenced. They’ve mattered.

And that’s T.A. Peterman’s real legacy—not just the trucks, but the standard he set for durability that influenced the entire industry. Competitors had to match Peterbilt’s toughness or lose customers, raising quality across all manufacturers and making all trucks better.

He created a business model based on customization, meeting specific customer needs instead of forcing everyone into standard specifications. That philosophy, allowing customers to specify exactly what they want, is now industry practice.

A Lasting Impact

Peterbilt trucks inspire a loyalty that goes beyond mere transportation equipment. Walk through a truck stop anywhere in America, and you’ll see Peterbilts—old ones from the 60s still working, new ones with all the latest technology. Drivers choose Peterbilt specifically; they want that particular truck, that particular brand.

That means something. Eighty-five years after one frustrated plywood mill owner decided to build better trucks, Peterbilt is still building them, still innovating, still competing, still mattering.

In a world increasingly divided by nationalism and xenophobia, Le Chambon’s example has become more relevant, not less. Every time a government closes its borders to asylum seekers, every time a politician claims that protecting the vulnerable is too dangerous or too expensive, someone points to a small village on a French plateau and asks, “If they could do it with nothing, why can’t we?”

Conclusion

Peterbilt has become larger than just trucks. Movies feature them, country songs mention them, and truck shows celebrate them. There’s pride in owning a Peterbilt that goes beyond practical considerations. It’s identity.

But nostalgia doesn’t pay bills. Peterbilt has to keep innovating. Their Super Truck project, developed with government funding, achieved 75% better fuel economy than baseline trucks using aerodynamics, lightweight materials, and advanced powertrains. Most of that technology won’t reach production trucks for years, but it shows that Peterbilt is investing in future technology.

The challenge ahead is daunting, but if history has taught us anything, it’s that Peterbilt has always risen to the occasion, proving that with determination and innovation, they can continue to lead the way in the trucking industry.