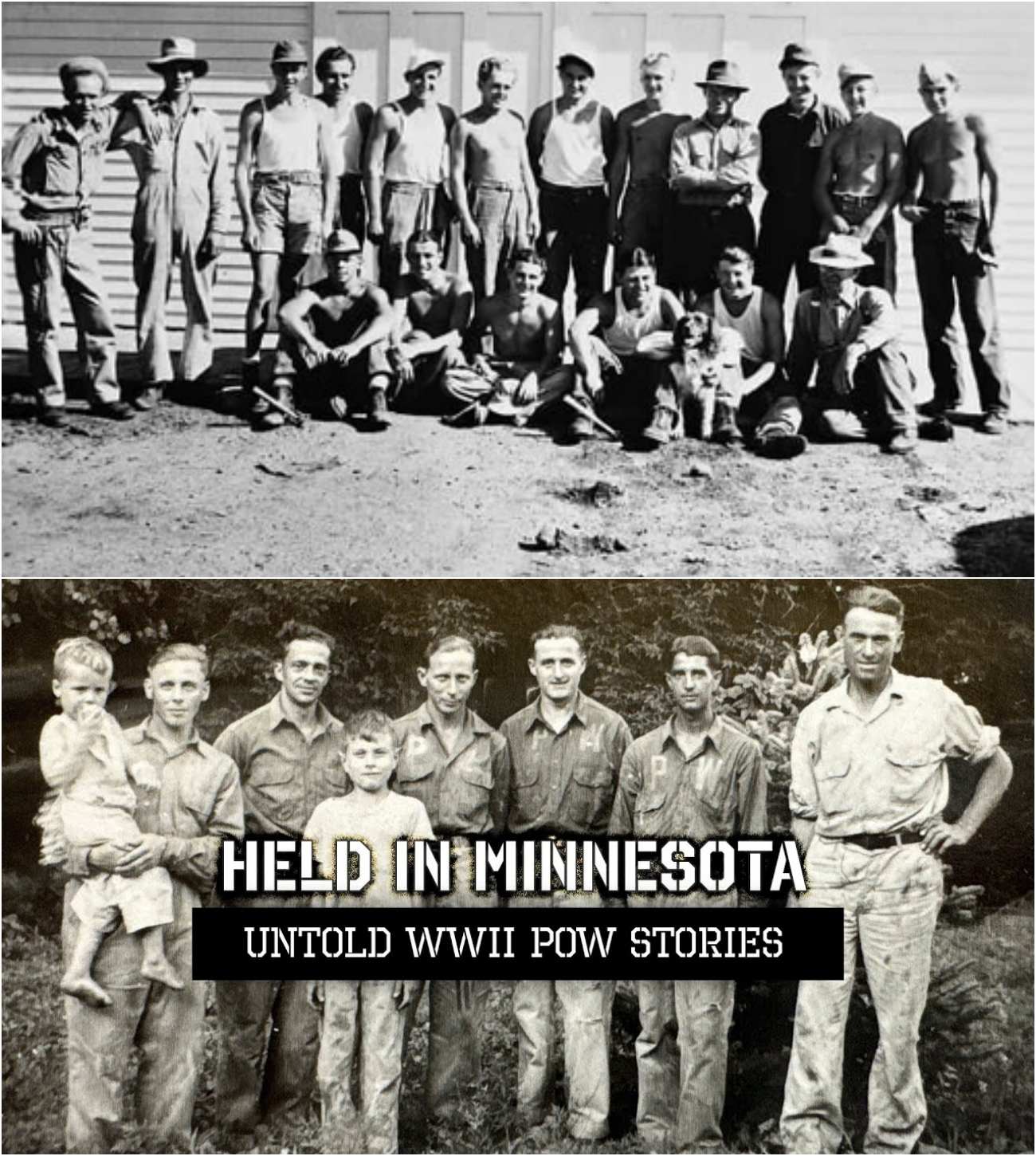

Held in Minnesota: Untold WWII POW Stories

In the winter of 1944, with the war still raging overseas, the United States faced a critical shortage of labor. With young men off fighting in the war, agricultural production in many parts of the country was struggling to keep up. Minnesota, with its vast farmlands, was no exception. But instead of relying solely on local labor or military conscripts, the U.S. government turned to a resource they had once viewed as an enemy: German prisoners of war.

Hundreds of prisoners from the Afrika Korps and other German military units were brought to Minnesota. They arrived in a state still reeling from the effects of the Great Depression, a state that had already weathered the storm of war but was now facing new and unexpected challenges. The prisoners, once feared and hated for their role in the war, were now tasked with one of the most critical jobs: feeding the people who had been providing for the war effort.

These prisoners were housed in camps spread throughout the state, and in each camp, a unique story unfolded—one of mutual respect, human decency, and sometimes, friendships that transcended national and ideological borders.

First Impressions: Uncertainty and Fear

When the German prisoners first arrived in the small town of Olivia, Minnesota, the reaction was one of fear and skepticism. The community had heard rumors about the prisoners—the same propaganda that had painted them as dangerous, violent men. Local residents were unsure how to interact with these men, who had once been the enemy and were now living among them.

But that fear began to melt away when the prisoners, many of whom were young men barely out of their teens, showed a completely different side to the villagers. They were not soldiers—they were workers, men who had been thrown into a war they hadn’t chosen, and now they were simply trying to survive.

One of the first notable stories comes from the small town of Princeton, where the prisoners were sent to work on a local potato farm. The farmer, O.J. Odegard, was a man who treated the prisoners with surprising kindness. Instead of treating them with disdain or suspicion, Odegard fed them well, treated them like human beings, and even allowed them to interact with the local community.

The prisoners, in turn, began to form bonds with the locals. They would sing as they worked, their voices filling the air with melodies that were familiar to their homeland. The sound of their singing was a reminder that, despite the uniforms they wore, they were just men, struggling to find their way home.

A New Kind of Warfare: Human Decency in Action

As the weeks passed, something remarkable began to happen. In the evenings, the German prisoners were allowed to leave the camp and socialize with the locals. Some of the women who worked at the nearby St. Ansgar Hospital would meet the prisoners behind the barns or in the fields. At first, the idea of fraternizing with the enemy seemed outrageous, but the connection was undeniable. They spoke the same language, and for many of them, the war was no longer the focus—it was about survival, about connecting with others, about being human.

The German prisoners began to share their stories, and the locals shared theirs. The boundaries between “us” and “them” blurred as the weeks went on. In one instance, a young German soldier, who had once been a baker in his hometown, was invited to a local family’s house for dinner. The families fed the prisoners like they would feed any farmworker, without prejudice, without hate.

A Story of Reconciliation and Regret

But it wasn’t all smooth sailing. The villagers and the prisoners had to navigate the complexities of war and post-war tensions. Many locals found it difficult to reconcile the fact that they were sharing meals and stories with the very men who had been fighting their sons and fathers. In one instance, a couple of young women from the town found themselves spending time with the prisoners, and when they were caught, they were briefly arrested for “fraternizing with the enemy.”

In another instance, the Odegard family’s bond with their German POWs became so strong that the prisoners began to help with more than just farm work. They would assist with repairs around the house and even help with other odd jobs, treating the family with the kind of respect that had been rare in the years before.

A Survivor’s Perspective: Longing for Peace

Alfred Mueller, a German POW who spent time in Minnesota, later recalled his experiences in the country. “It was the best time of my life as a prisoner,” he said. “The Americans treated us with kindness, which was more than we could have hoped for.” After the war, Mueller, like many other prisoners, returned to Germany but eventually emigrated to the U.S., settling in Iowa. He worked for years in construction and later became a strong advocate for peace and understanding, believing that his time in Minnesota had changed his life forever.

The kindness that the Minnesota farmers showed the prisoners was not just a reflection of the generosity of spirit but also of the greater principle of humanity. For these prisoners, who had once been enemies, the way they were treated in Minnesota gave them a glimpse into what a better world could look like—a world where people were treated based on their character, not their nationality.

The Lasting Legacy: How Minnesota’s POW Story Shaped History

Years later, the story of these POWs would not just become a memory, but a lesson in how compassion can break down the walls of hatred built by war. The German POWs who worked in Minnesota were often surprised at how well they were treated, with some even saying that their time in the U.S. had shown them what true humanity looked like.

Today, the legacy of Minnesota’s POW camps serves as a testament to the power of human decency. It reminds us that even in the darkest of times, kindness can emerge, and even the most hardened enemies can find common ground when treated with respect and dignity.

For those who lived through the experience, the memories are still fresh. They recall the moments when they shared a meal with someone they once considered the enemy, the stories exchanged in broken languages, and the quiet moments of understanding that transcended national borders and wartime allegiances.

In the end, the story of the German POWs in Minnesota is not just about the food and the work they did. It’s about how humanity, when given a chance, can outshine the hatred and violence of war, and how compassion, even in small acts, can change the course of history.