How One Canadian Soldier’s “Crazy” Idea Rescued 34,000 Jews From Extermination Camps

In April 1945, as the world bore witness to the horrors of the Holocaust, a Canadian soldier named Lieutenant Colonel Ben Dunkelman found himself in a situation that would test the limits of human compassion and ingenuity. The scene was Bergen-Belsen, a Nazi concentration camp in Germany, where British and Canadian forces had just arrived to liberate the survivors. However, instead of a joyous liberation, the soldiers were met with hell on earth.

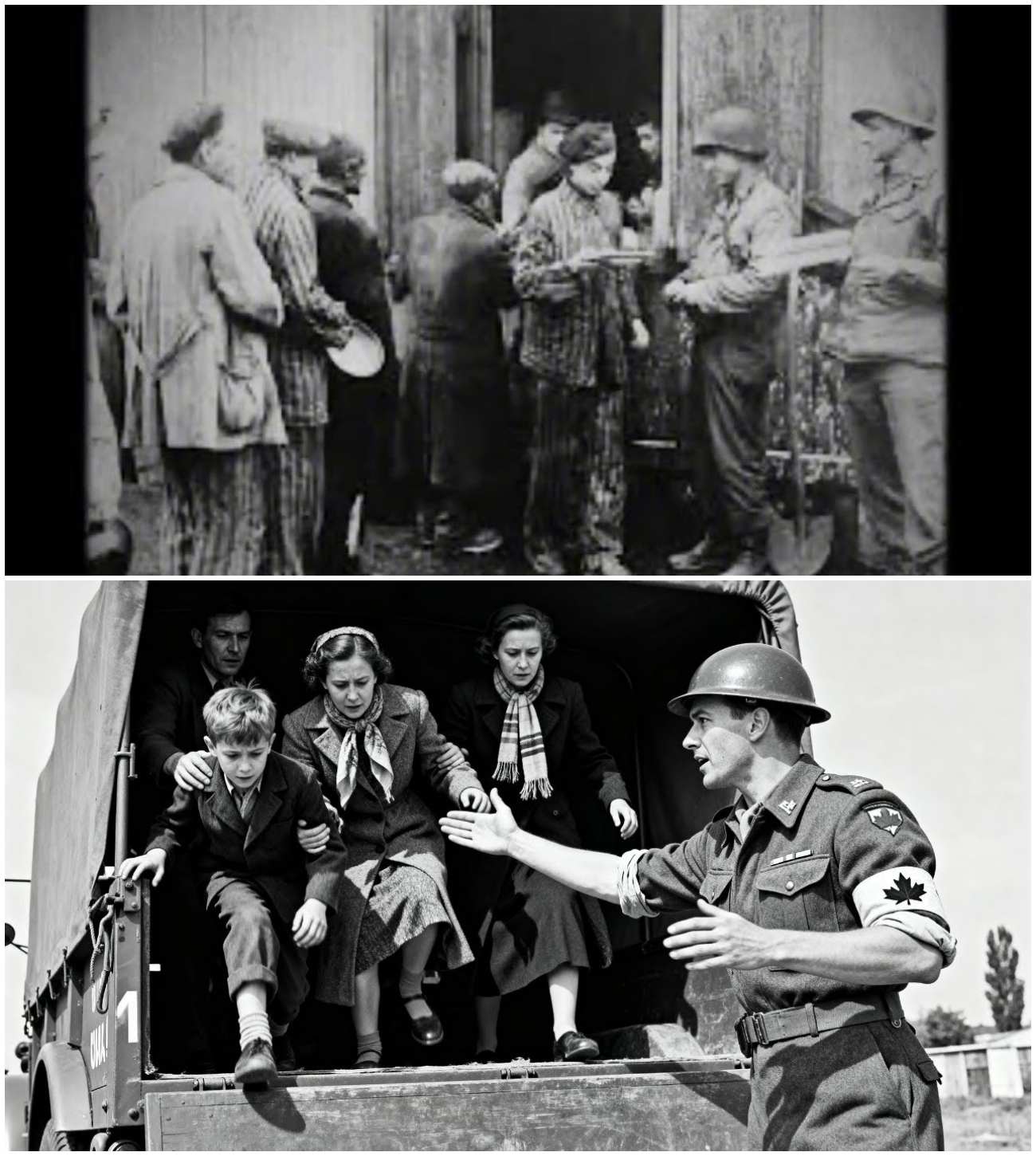

The Horrors of Liberation

As British tanks rolled through the gates of Bergen-Belsen, the soldiers were immediately confronted by the stench of death and disease. Bodies lay stacked like firewood, and the camp was filled with the skeletal remains of those who had survived the extermination camps across Europe. The sight was so horrific that grown men fell to their knees, overwhelmed by the reality before them.

In the first week after the liberation, the death toll climbed alarmingly. Despite the valiant efforts of medical teams working around the clock, 400 people died each day—not from Nazi bullets or gas chambers, but from the aftermath of their horrific experiences. The conventional medical approach, which had saved countless soldiers in the past, was failing miserably in this unprecedented crisis.

The Medical Dilemma

The doctors in charge, seasoned veterans of wartime medicine, believed they were doing everything right. They followed established protocols: feeding the starving slowly, providing clean water, and treating diseases with the best available medicine. Yet, the reality was grim. Prisoners who received their first real meal in months died within hours, as their bodies could not handle the sudden influx of food. Others drank too much water too quickly, leading to heart failure. Typhus spread through the barracks faster than the medical teams could contain it.

As the death count continued to rise, British commanders faced a grim calculation: 30,000 more lives would likely be lost in the coming months, even with the best medical care. The experts had spoken, and their conclusion was bleak: these deaths were inevitable.

Dunkelman’s Revelation

Amidst the despair, Lieutenant Colonel Ben Dunkelman stood in the mud of Bergen-Belsen, refusing to accept the grim prognosis. At just 28 years old, Dunkelman had fought bravely across Europe, from D-Day to this wretched camp. He was not a doctor; he had no medical training. But he was Jewish, and the faces of the dying prisoners reminded him of his own family back in Toronto.

Dunkelman’s heart broke as he watched the suffering unfold. He walked through the camp for hours, observing the appalling conditions: barracks overcrowded with people, a single water pump serving thousands, and a medical tent overwhelmed with patients. The system was failing, and he realized that the conventional medical wisdom was inadequate for such a catastrophic situation.

That night, by lamplight in his tent, Dunkelman wrote furiously, fueled by anger and desperation. He understood that the military was trying to save individuals when they needed to save a population. Every rule in the medical handbook was designed for normal situations, but this was anything but normal. The idea came to him, fully formed yet dangerous: move them, all of them. Get them out of this death trap and spread them across multiple locations where they could receive proper care.

The Bold Proposal

Dunkelman knew the risks associated with moving critically ill patients. The stress of transport could easily kill them, and the doctors would likely dismiss his idea as reckless. But he also understood that the current situation was a slow death sentence. He resolved to present his plan to the senior officers the next morning, fully aware that he might be ridiculed or disciplined for wasting their time.

When Dunkelman entered the command meeting, he was met with skepticism. The room was filled with British officers, medical staff, and logistics commanders, all discussing the rising death rates. He took a deep breath and laid out his proposal: “We need to move 34,000 people out of this camp within 72 hours.”

Laughter erupted, followed by angry murmurs. A British medical colonel stood up, red-faced, and dismissed him outright. “You want to move dying patients? You will kill them faster than the typhus. Sit down, Lieutenant Colonel. Leave medicine to the doctors.”

But Dunkelman refused to back down. He presented his calculations, arguing that moving the patients to clean facilities would save lives, even if they lost a small percentage during transport. “Right now, 400 people die here every day. If we can save even a fraction of them, we must try.”

Gaining Support

The medical staff pushed back hard, citing logistical challenges and the dangers of moving critically ill patients. However, Brigadier Glenn Hughes, the deputy director of medical services, stepped forward. He was a seasoned military doctor who had witnessed the horrors of war firsthand. After reviewing Dunkelman’s numbers, he decided to give him a chance. “You get your test: 500 patients, 24 hours to show results. If your death rate is higher than ours, this conversation ends forever.”

The next morning, Dunkelman sprang into action. He commandeered every vehicle he could find—German army trucks, abandoned ambulances, even civilian buses left behind in the chaos. He gathered medical orderlies, nurses, and volunteers willing to try something radical. The plan was precise: each patient would receive a carefully calculated amount of food and water before transport to minimize the risk of shock.

The Evacuation Begins

As the sun rose, the first truck was loaded with patients so thin that their bones showed through their skin. Many could not walk, and volunteers carried them on stretchers, navigating the treacherous ground. Each truck held 20 patients, packed with blankets and hot water bottles, while medical staff monitored vital signs throughout the journey.

The 15-kilometer trip took three hours, with trucks moving at walking speed over bombed-out roads. Dunkelman rode in the lead vehicle, calculating mortality rates in his head. They reached the nearest town by noon, where empty German barracks were transformed into makeshift hospitals. Each patient received their own bed, providing the space and care they desperately needed.

Proving the Plan

After 24 hours, the results of Dunkelman’s test were in. Of the 500 patients moved, 15 had died during transport—a 3% mortality rate. In contrast, 60 patients had died from the same starting group who remained in Bergen-Belsen—a shocking 12% death rate. Dunkelman had proven that moving critically ill patients could be safer than leaving them to die in place.

Brigadier Hughes was impressed. Dunkelman’s operation would be expanded dramatically. Over the next eight days, Dunkelman and his team managed to move 34,000 people to 12 different locations, converting German barracks, schools, and factories into functioning hospitals almost overnight.

The Challenge of Authority

However, Dunkelman’s success did not come without challenges. Three days into the operation, he was summoned to headquarters, facing potential court martial for commandeering enemy vehicles and using prisoners for labor. A general confronted him, demanding an explanation for his actions.

Before Dunkelman could respond, Brigadier Hughes intervened, presenting the staggering success of Dunkelman’s operation. The statistics spoke for themselves: a dramatic reduction in mortality rates and lives saved. The general was forced to reconsider, and Dunkelman was allowed to continue his work.

A Lasting Legacy

As the operation progressed, Dunkelman’s methods proved effective, and the death rate continued to plummet. The medical establishment, which had initially doubted him, began to take notice. Over 8 days, Dunkelman and his team moved 34,000 people, saving thousands of lives against all odds.

In the aftermath, Dunkelman returned to Canada, where he lived a quiet life, rarely speaking of his experiences at Bergen-Belsen. However, the impact of his actions did not go unnoticed. By the 1950s, NATO adopted mass casualty evacuation protocols based on Dunkelman’s innovative methods, revolutionizing military medicine.

Dunkelman’s approach became the foundation for modern combat medicine, emphasizing the importance of moving populations away from sources of suffering and providing immediate care. His legacy lived on, influencing how future conflicts were managed and how humanitarian crises were approached.

Conclusion: The Measure of Humanity

The story of Lieutenant Colonel Ben Dunkelman is not just one of bravery; it is a testament to the power of unconventional thinking in the face of unimaginable horror. He refused to accept the status quo, challenging the medical norms of his time to save lives.

Dunkelman’s legacy teaches us that sometimes the most important actions come from those who dare to think differently. He demonstrated that in the face of overwhelming odds, the courage to act—no matter how “crazy” the idea—can lead to miraculous outcomes. The measure of humanity is not just found in heroic acts, but in the willingness to fight for the lives of others, to challenge established norms, and to refuse to accept that death is inevitable when hope remains.

In the end, Dunkelman’s actions saved 34,000 futures, proving that sometimes, the most profound changes come from those who are willing to risk everything for the sake of others.