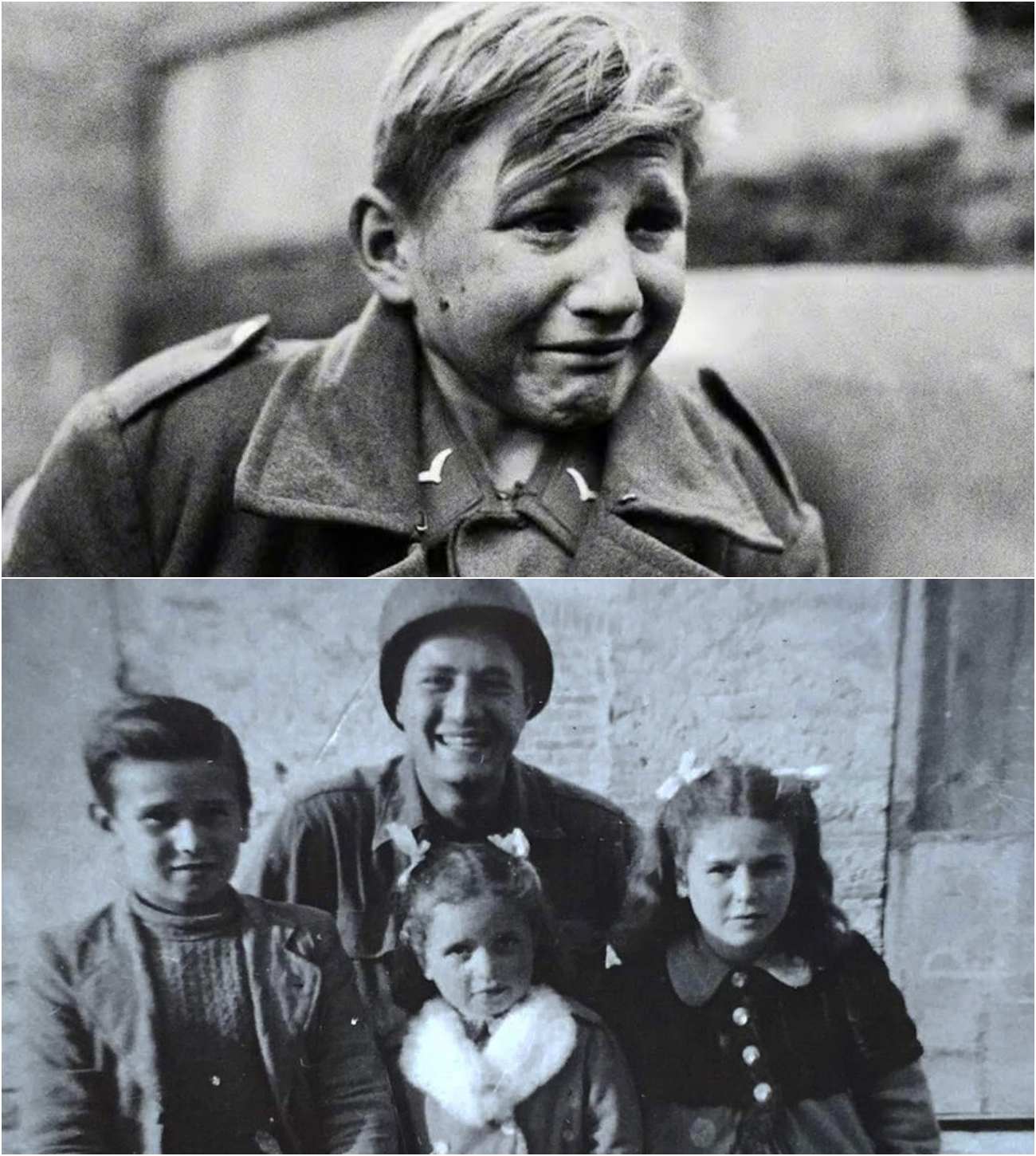

German Orphans Couldn’t Believe American Soldiers Adopted Them After the War

April 28th, 1945. Private First Class Daniel Hoffman, a battle-hardened soldier, stood in the ruins of Magnabberg, Germany, his M1 Garand aimed at a figure emerging from the wreckage. He was ready to fire at what he believed to be another desperate German soldier. But as the figure raised his hands in surrender, Hoffman’s heart sank. The boy was no more than 14 years old, his frail frame draped in a too-large uniform. His eyes, wide with terror, looked back at Hoffman, pleading: Please don’t shoot.

Hoffman lowered his weapon, his hands trembling for the first time since the beaches of Normandy. His fellow soldier, Sergeant Robert Mitchell, stood behind him, staring in disbelief. “Jesus Christ,” Mitchell whispered. “He’s younger than my son.” In that moment, both men realized the true horror of what they were witnessing. The Nazis, in their final, desperate attempts to turn the tide of war, had begun drafting children as soldiers—boys who had no place on the battlefield except as cannon fodder.

These boys, many as young as 12, were taken from their schools, homes, and bombed-out neighborhoods. Armed with weapons far too large for them, they were sent to fight a war they barely understood. Some of them had been indoctrinated into the Hitler Youth from the age of six, taught that dying for Hitler was the highest honor. They were told that the Americans were subhuman monsters, that surrender would mean torture and death. But when they found themselves in the hands of the very soldiers they were trained to kill, their world crumbled.

The First Encounters: Mercy Over Revenge

For American soldiers advancing through Germany, the discovery of these child soldiers posed a profound moral dilemma. These boys, armed with real weapons and trained to fight, posed legitimate tactical threats. But they were still children—children who had been forced into a war they didn’t understand. Staff Sergeant James Walsh, part of the Third Armored Division, described his first encounter with a group of these young soldiers near Paderborn, Germany.

“We took fire from a building and returned it,” Walsh recalled. “When we cleared the position, we found six kids inside. Two were dead. The others were maybe 13 or 14, crying and begging not to be killed.” Walsh, a father of three, sat down on the floor and began to sob. “We’d killed children because they were shooting at us, and there was no way to make that feel right.”

The American soldiers found themselves caught in a moral paradox. They were fighting for survival, but at the same time, they couldn’t ignore the innocence in the eyes of these young boys. At that moment, a shift began to occur in the way soldiers interacted with the children they captured. Rather than shooting them on sight, many soldiers began to go out of their way to capture the boys alive. They would hold fire longer than tactically necessary, aim to wound rather than kill, and even use loudspeakers to call for surrender. It wasn’t official policy, but it was a practice that emerged organically from the individual moral choices of soldiers who couldn’t bring themselves to kill children, even if they were enemies.

The Orphan Crisis: A Generation Lost

By the time the fighting ended in May 1945, the American forces found themselves responsible for managing thousands of captured child soldiers. But these boys were not just soldiers—they were orphans. Many had lost their families to bombings or had been separated during evacuation efforts. Others had no families left to return to, as their parents had been killed in the war. In total, by the end of the war, approximately 500,000 German children had been orphaned, with 150,000 needing care in American-occupied zones.

The American military, unprepared for this humanitarian crisis, quickly converted old military barracks and requisitioned buildings into orphan facilities. Army Chaplain Captain William Hayes, stationed at Camp Sheridan near Frankfurt, organized the processing of hundreds of captured boys. His report to division headquarters reflected the growing discomfort American soldiers felt about treating these children as enemy combatants. “These are not soldiers in any meaningful sense,” Hayes wrote. “They are children who were armed and abandoned.”

At these camps, the American soldiers did what they could to provide care. They distributed extra rations, ensured medical care was prioritized, and even organized educational programs. The soldiers—many of whom were fathers themselves—taught the boys English, played games with them, and did their best to restore some semblance of normality to their shattered lives.

For many of the boys, this kindness was as incomprehensible as the violence they had witnessed. 14-year-old France Becker, who was captured near Nuremberg, recalled how the first American soldier he encountered offered him chocolate and taught him how to throw a baseball. “The Americans were supposed to be monsters,” Becker said. “Instead, they gave me chocolate and taught me how to throw a curveball.”

A New Kind of Fatherhood: Adoption in the Aftermath

As the days turned into weeks, and the weeks into months, the reality of the orphan crisis became even more apparent. Many of the children in the camps had nowhere to go. Their families were gone, and their homes had been destroyed. They were stuck in limbo—caught between their past as enemy soldiers and their uncertain future as orphans in a foreign country.

Some of the American soldiers couldn’t walk away. They saw in these children a reflection of their own sons, their own brothers. And so, against all odds, a new movement began. American servicemen, many of whom had lost friends and comrades to the war, began petitioning the military to allow them to adopt these German children. It started as a few informal requests, but soon the number of soldiers seeking to adopt grew. In 1945, the first documented case of adoption occurred when Staff Sergeant Thomas Riley petitioned to adopt 16-year-old Klaus Dietrich. “This boy has no family, no home, and no future in Germany,” Riley wrote. “I have the means to provide for him, the desire to raise him, and his consent.”

The military, struggling to find a legal framework for such adoptions, worked with the American Red Cross and civilian adoption agencies to create a process. By 1946, a system was in place, and over the next two years, approximately 180 adoption petitions were filed. Of those, 127 were approved, and 134 orphans—many of them former child soldiers—were brought to America.

The Journey to a New Life

In March 1947, the first group of German orphans traveled from Bremerhaven to New York, escorted by their new American fathers. Among them was 15-year-old Verer Schmidt, who had once tried to kill Americans but now stood side by side with his adoptive father, Sergeant James Walsh. Schmidt could hardly believe the transformation in his life. “I kept thinking it wasn’t real,” he recalled years later. “Two years ago, I tried to kill Americans. Now, I was going to live in America with one of them.”

The story of these German orphans, adopted by the very men who had fought against them, became a symbol of the incredible capacity for mercy in the aftermath of war. The American families who adopted them faced numerous challenges—language barriers, trauma, and a society that questioned their choices. But the overwhelming pattern was one of successful integration. The orphans learned English, attended school, and became part of their new communities. They grew up with loving families, a future that would have been unimaginable if not for the mercy of the soldiers who chose fatherhood over hatred.

Redemption in the Ruins

For the American veterans who adopted these children, the experience was not without its psychological challenges. They had fought against the Nazis, lost friends and comrades, and seen the worst of humanity. Now, they were raising children who had once been taught to kill them. But over time, these bonds of love and compassion proved stronger than the ghosts of war. The soldiers who had once seen these children as enemies now saw them as sons.

The story of these adoptions, though not widely known, is a testament to the possibility of redemption after even the most brutal conflicts. It shows that mercy can transcend nationality, that children are children regardless of the uniforms they wore, and that sometimes, the greatest victories are not won on the battlefield, but in the quiet moments of reconciliation.