When 21 Japanese Planes Attacked One F4U Corsair — His Response Shocked the Pacific

.

.

.

Lone Corsair vs. 21 Fighters: The 12-Minute Battle That Stunned the Pacific

Piva North, Bougainville — January 30, 1944

At 06:15 on a humid, pre-dawn morning in the South Pacific, a young Marine lieutenant cinched his harness, checked his gun switches, and watched a line of Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo bombers crawl toward the runway like loaded freight trains.

His name, according to squadron paperwork and later accounts, was First Lieutenant Robert Hansen—23 years old, already a rising legend among Corsair pilots, and—if the tallies held—dangerously close to the pantheon of Marine aces. He was also, by the calendar, one week from rotating home.

Ahead of him sat the day’s arithmetic problem, written in fuel, altitude, and probability: 18 Avengers would fly into the jaws of Rabaul, the fortress complex anchoring Japan’s defenses around Simpson Harbor. Their escort: eight F4U Corsairs.

Japanese intelligence, U.S. briefings, and bitter experience all agreed on one point: Rabaul could put up dozens of fighters quickly, and it was ringed by radar stations and anti-aircraft batteries. Marines had already paid heavily for every attempt to crack it. Rabaul wasn’t just a target. It was a grinder.

Hansen’s response to that grinder—especially what happened when 21 Japanese fighters rose to meet the strike—would become one of those stories aviators trade in mess halls: part tactics lesson, part warning, part myth, and part grim truth.

And it all began with a decision that most pilots are trained not to make.

A Mission Built on Bad Odds

In the briefing hut, the plan was clean on paper: bombers in at roughly 12,000 feet, fighters above at 15,000. Approach from the southeast. Hit Simpson Harbor’s infrastructure. Protect the Avengers through the danger window and bring everyone home.

It was standard doctrine—a doctrine written in loss reports.

American pilots had learned the hard way that Japanese Mitsubishi A6M “Zero” fighters could turn inside almost anything they flew. The Corsair’s strengths were different: speed, armor, firepower, dive performance. The rule was repeated like scripture:

Don’t turn with a Zero.

Dive, strike, and climb away. Keep your energy. Stay fast.

But by late January 1944, Hansen had gained a reputation for treating doctrine as a suggestion, not a law.

Fellow pilots described him as precise—almost mathematical—in how he hunted. Where others stayed with formation discipline, he had a habit of breaking away and diving straight into enemy groups to disrupt their attack and draw pressure off the bombers.

Tactically, it could work.

Statistically, it could get you killed.

“Butcher Bob”: The Making of a Reputation

Accounts of Hansen’s earlier combats describe a trajectory that looked, frankly, unnatural.

He arrived in the South Pacific in mid-1943. His first victories came the way many pilots earn them: a clean shot here, a lucky break there, careful teamwork, a little fortune.

Then something changed.

The story most often repeated begins with a mission over Simpson Harbor in mid-January. Hansen separated from his squadron and found himself alone above Japanese fighters lining up to strike American bombers. Instead of running to rejoin cover—standard procedure—he dove into the formation. Within minutes, he was claiming multiple kills. He landed with his aircraft punched full of holes and his fuel gauge hovering near empty.

Other pilots started calling him “Butcher Bob.” It wasn’t an insult. It was nervous admiration.

Because men who fight like that tend to end up as memorials.

And yet he kept returning—each time with more holes in his plane and more marks on the scoreboard.

His commanding officer reportedly tried to ground him more than once. Hansen had “done enough,” the argument went. There was no need to keep gambling. He had earned his rotation.

But wars don’t care about schedules.

On January 30, intelligence flagged convoy movement near Rabaul and an opportunity too big to ignore. Every available bomber would fly. Every available fighter would escort.

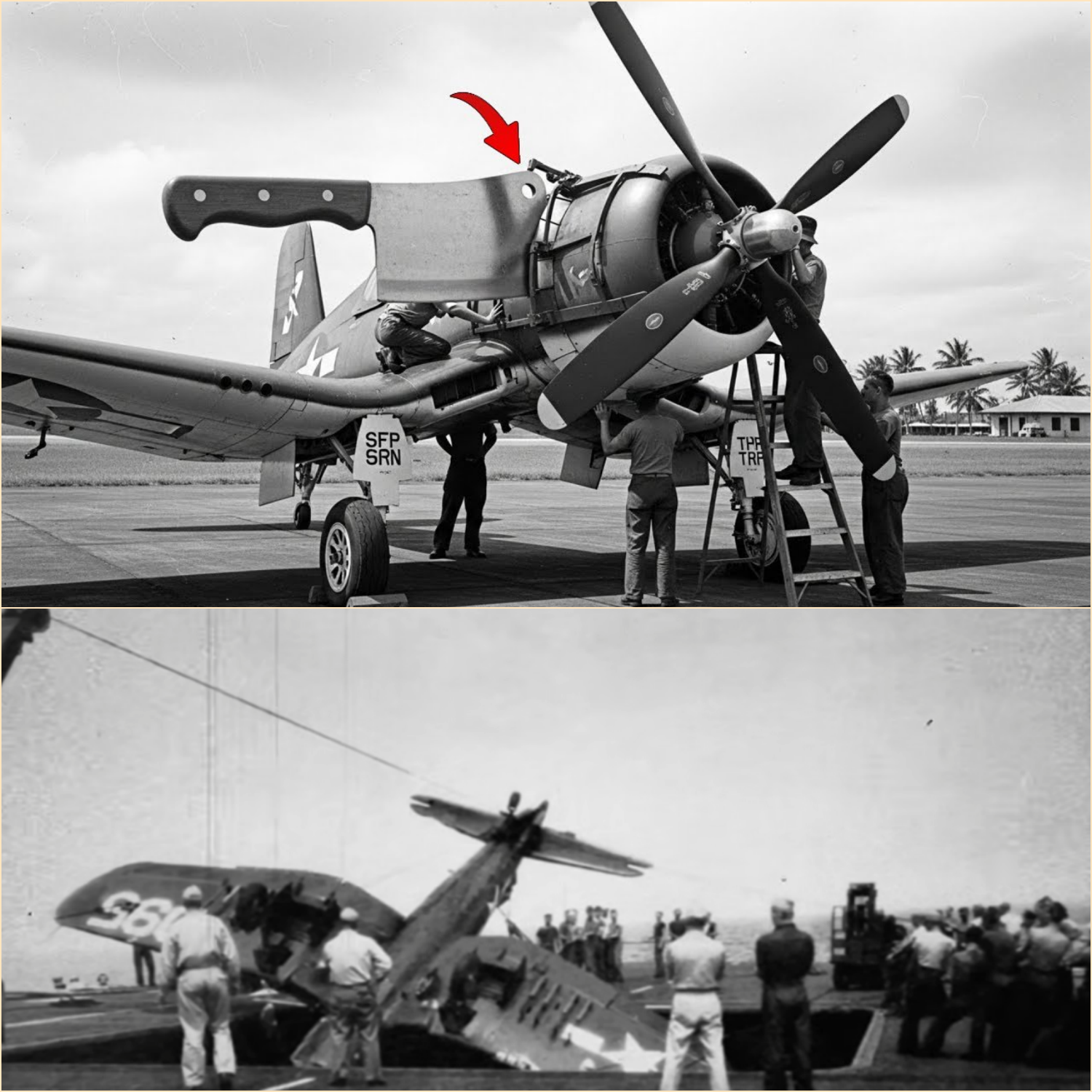

And Hansen climbed into the same Corsair he’d been flying for weeks—Bureau Number 56039 in some accounts—powered by the legendary Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp, a radial engine that could drag an F4U past 400 mph and haul it back out of dives that would tear lesser aircraft apart.

At 06:48, he taxied into position.

By 07:30, the strike package was crossing the northern coast of Bougainville. Simpson Harbor lay ahead.

Contact: Twenty-One Climbs Out of Rabaul

There is a moment in every escort mission when the radio goes quiet—not because the air is calm, but because everyone is listening.

Then someone calls it.

“Bandits.”

The sighting came as the strike neared the danger corridor: 21 Japanese fighters climbing to meet them. Observers identified the group as mostly Zeros—reports cite 17 A6Ms—with a smaller number of Nakajima Ki-44 “Tojo” fighters.

The Zero had dominated early Pacific air combat through turn performance and pilot skill. The Corsair held an advantage in speed and durability, but only if flown the right way.

Standard escort doctrine demanded that the Corsairs stay with the Avengers, maintain protective altitude, and force attackers to come into their guns.

Hansen didn’t.

As the other seven Corsairs held position, Hansen rolled inverted—an aerobatic move that set his aircraft nose-down—and dove alone toward the incoming Japanese formation.

From a distance, it would have looked like suicide.

From the cockpit, it was an attempt to reshape the fight before it began.

One fighter, sacrificing the safe geometry of escort, tries to scatter the attackers—pulling them away from the bombers and forcing them into a chasing fight where they lose organization.

It’s not reckless if it works.

It’s fatal if it doesn’t.

The First Kill: Breaking the Formation

In the dive, Hansen’s Corsair accelerated past 400 mph. He aimed for the lead Zero. The logic was simple: kill the leader, disrupt the group, force hesitation.

At roughly 400 yards, he fired.

The Corsair carried six .50-caliber Browning machine guns—brutal, reliable, and devastating at convergence range. Tracer fire walked into the Zero’s fuselage. The Japanese fighter shuddered, trailed smoke, rolled over, and fell into a spin.

One down. Twenty remaining.

Hansen pulled out low and used his speed to punch through the Japanese mass before they could fully react. Then he reversed and climbed—seeking altitude, seeking options.

The Japanese formation had done what he wanted: it broke.

But the price came immediately.

A large portion of the enemy—accounts say around 15 fighters—turned to pursue Hansen. A smaller number continued toward the bombers.

The Avengers got breathing room.

Hansen got a tail full of enemies.

Fifteen Behind Him: The Fight Becomes Personal

A pursuer opened fire. Tracers flashed past Hansen’s canopy. A round punched his tail; another nicked his wing root. Not catastrophic. Not yet.

Hansen snap-rolled hard. The Corsair’s roll rate—one of its underappreciated strengths—made it difficult for a Zero to stay perfectly aligned in a firing solution.

He dove again to build speed, then climbed sharply, bleeding airspeed but regaining altitude. It was energy fighting at the edge of control: dive, climb, roll, reverse, repeat.

Below him, Japanese fighters scattered across different altitudes, searching for him.

That scattering—the collapse of discipline—was another tactical win. A tightly coordinated group is far more dangerous than individual hunters. Lose the formation, lose the advantage.

From above, Hansen picked targets like a hawk.

He dove on another Zero from high six o’clock—its blind spot—and fired at close range. The second aircraft disintegrated, breaking apart in the air.

Two down.

Now, every Japanese pilot knew where he was.

Tracers began converging from multiple angles. Hansen pulled high-G turns. The edges of vision gray. The body crushed into the seat.

And still, he pressed the attack.

The “Circle”: A Trap Hansen Tried to Break

At some point in the running fight, the remaining Japanese fighters—no longer scattered—attempted to re-form into a defensive circle. The tactic is known in Allied terminology as the “Lufbery Circle”: aircraft fly a rotating wheel so that any attacker diving onto one fighter gets shot by the next fighter behind it.

It’s a geometry of mutual support.

And for an aggressor, it can be a death trap.

The “safe” call here would be: disengage. Rejoin escort. Go home.

But witnesses and later narrative accounts claim Hansen made the opposite calculation: the bombers were already turning away, safe for the moment. The circle still contained fighters that could threaten other Allied aircraft. He still had ammunition. He still had altitude.

He went back in.

This time, he attacked not a single aircraft, but the circle’s structure—diving at a tangent so his path aligned with the circle’s rotation. The closure rate dropped. The time window tightened.

At close range he fired, destroying another Zero.

Three down.

Then, rather than climbing away, he leveled off inside the circle—momentarily flying “with” the rotating formation. In that brief instant, Japanese pilots behind him couldn’t fire without risking friendly hits, and those ahead couldn’t turn back without collision.

It was a knife-edge trick: geometry as armor.

He used the seconds to fire again.

Four down.

The circle shattered into a chaotic furball—fighters breaking in all directions, losing mutual support.

And chaos is where a pilot with superior speed and decision-making can survive the odds.

The Cost: Forty-Seven Holes and a Failing Engine

But fights like that don’t end neatly.

As the pursuit continued, Hansen’s aircraft took increasing damage. Reports describe:

holes in control surfaces,

punctures through instrument panels,

hits on armor plate behind the seat,

hydraulic leaks,

and—most critically—an engine and cooling system pushed into failure.

The Corsair could absorb punishment, but the Double Wasp still needed oil pressure and temperature control. Hansen began to face a grim, mechanical countdown: stay at full power to keep distance from pursuers and risk seizing the engine—or throttle back and let enemy fighters close.

He chose power.

Eventually, the remaining Japanese fighters broke off pursuit—whether due to fuel, tactical priorities, or the distance from their base. Hansen turned southeast for Bougainville, nursing an overheating engine and an aircraft that no longer handled like a complete machine.

Near Piva North, oil pressure fell. The engine began to knock—then seized.

The Corsair became a glider.

No engine means no second chances, especially over jungle and sea.

Hansen managed a dead-stick landing, touching down clean and rolling to a stop as fire trucks converged.

Ground crew counted dozens of bullet holes—a figure often cited as 47 in later retellings—along with severe control and structural damage.

In the debriefing, Hansen claimed multiple kills. But air combat accounting is strict: without confirming wreckage, gun-camera film, or witness corroboration, “kills” can be downgraded.

Reviews reportedly confirmed some of his claims—often cited as four that day—while others remained “probable.”

Even so, the January 30 fight added a new chapter to a growing legend: one pilot, one Corsair, and a formation of enemy fighters that should have overwhelmed him.

He had protected the bombers.

He had survived.

And he was—if the rotation schedule held—still a week from home.

Four Days Later: The End of the Story

The tragedy of such stories is that they rarely stop at the high point.

On February 3, 1944, accounts say Hansen volunteered for another mission—despite being close to rotation. The strike went well. Then, on the return leg, he broke formation and dove to strafe an enemy installation near Cape St. George.

Anti-aircraft fire erupted. His aircraft struck the water during pull-up. The Corsair tore apart and exploded. No parachute. No raft. No radio call.

A squadron diary entry later noted simply that he did not return.

He was 23—one day before his birthday, by some accounts—days from the ship that would have carried him home.

Posthumous awards followed in later retellings and institutional memory. His name, in some versions of the story, lived on through squadron honors and memorial listings.

But the core fact that pilots remembered wasn’t the paperwork.

It was January 30:

A lone Corsair diving into 21 fighters—not because it was safe, but because the bombers behind him were vulnerable.

Why This Battle Still Matters

War stories often become morality plays—heroes and villains, clean courage and clean outcomes. But the reality in the cockpit is colder:

A pilot chooses an angle,

chooses a burst length,

chooses to climb or dive,

chooses whether to stay with the group or draw fire alone.

And every choice is paid for in probability.

Hansen’s January 30 engagement—whatever the exact final kill count—illustrates a truth of air combat that remains valid beyond World War II:

Sometimes you don’t win by outnumbering the enemy.

You win by breaking their geometry.

He didn’t defeat 21 planes in a tidy line. He disrupted them, divided them, and used speed, roll rate, and altitude to keep choosing the terms of engagement. It was violent problem-solving at 400 miles an hour.

And it bought the bombers time.

In the Pacific, that was often the difference between a mission returning and a mission becoming a list of names.