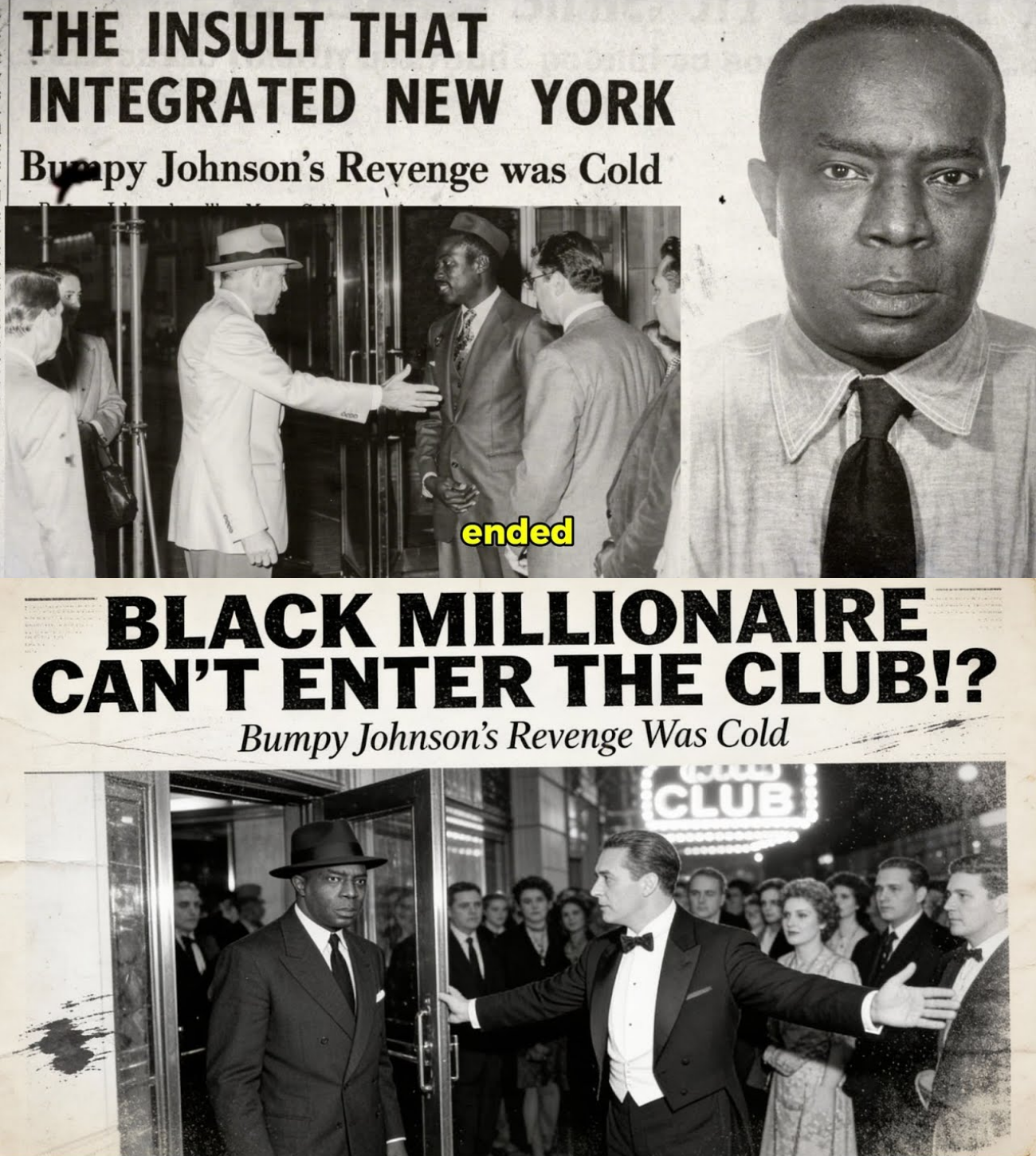

1935: R*cist Doorman Insults Bumpy Johnson at Whites-Only Club – What Happened Next Shocked New York

On the evening of September 19, 1935, a pivotal moment in the history of Harlem unfolded, one that would resonate for decades to come. It was a night when Ellsworth “Bumpy” Johnson, a significant figure in Harlem’s underworld, faced a racist doorman at the Cotton Club, an iconic venue known for its vibrant jazz performances and stark racial segregation. This encounter would ignite a movement that challenged the very foundations of racial discrimination in Harlem and beyond.

A Night at the Cotton Club

As Bumpy Johnson approached the Cotton Club, he was dressed impeccably in a navy blue suit, a crisp white shirt with French cuffs, and polished shoes that glimmered in the streetlights. He had earned this attire through hard work in his policy operations, and he intended to make a statement. The Cotton Club was a place where the wealthy white elite came to enjoy the talents of Black musicians like Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway, but it was also a venue that strictly enforced a whites-only admission policy.

Johnson had been invited to the club by Jacob Weinstein, a Jewish businessman with interests in Harlem. Weinstein believed that an exception could be made for someone as important as Johnson, but he was gravely mistaken. As Johnson approached the entrance, he was met by Thomas Murphy, the doorman, who blocked his path with a dismissive sneer.

“Where do you think you’re going, boy?” Murphy barked, his voice loud enough for the line of white patrons behind Johnson to hear. “This club is for white patrons only. We don’t serve colorards here, except as entertainers and staff. You need to get back to Harlem where you belong.”

The Insult

Johnson felt the weight of Murphy’s words, a blatant reminder of the systemic racism that permeated society. The doorman’s insult was not just a personal affront; it was a reflection of a larger societal issue—one where Black people could entertain, serve, and labor for white patrons but were denied the basic dignity of enjoying the fruits of their culture as equals. The onlookers, a mix of amusement and discomfort on their faces, waited to see how Johnson would respond.

In that moment, Johnson understood that arguing with Murphy would only lead to further humiliation, possibly even violence. Instead of reacting in anger, he chose a path that required immense self-control. He smiled—a cold, calculated smile that suggested he was memorizing Murphy’s face and the humiliation he had just endured.

With a nod that could have meant acceptance or something far more ominous, Johnson turned away from the Cotton Club and walked down West 142nd Street, his posture erect, his pace unhurried, giving no indication that he had just been publicly insulted.

A Moment of Reflection

As he walked through the streets of Harlem, Johnson allowed himself time to think. He found himself outside the Seavoy Ballroom, a venue that welcomed Black patrons and was owned by Black businessmen. Watching families and professionals enter the Seavoy without fear of discrimination ignited a realization in him.

The Cotton Club, despite being located in Harlem and relying on Black talent and labor, was owned by white businessmen who profited from Black culture while excluding Black patrons. Johnson recognized that this arrangement existed only because Black Harlem lacked the economic power and organizational capacity to challenge it. The owners believed they could maintain their discriminatory policies indefinitely because they assumed Black Harlem was powerless.

But Johnson had resources, connections, and a willingness to use unconventional methods to fight back. The insult he had suffered was not just a personal grievance; it was a call to action.

The Plan: Organizing for Change

Johnson walked to a payphone and made three critical calls that would set everything in motion. His first call was to Theodore “Teddy” Green, his attorney and closest adviser. The second was to Stephanie St. Claire, the queen of policy in Harlem, who controlled substantial gambling operations and had mentored Johnson. The third call was to Adam Clayton Powell Sr., a prominent minister and civil rights leader.

By midnight, Johnson had assembled a group of approximately 15 influential figures in the back room of a speakeasy on 133rd Street. This group included his top associates, representatives from other Black policy operators, union officials, and ministers from major Harlem churches. As he described the incident at the Cotton Club, he saw their faces shift from curiosity to anger, and then to determination.

“The Cotton Club turned me away tonight because I’m colored,” Johnson explained, his voice calm but intense. “The doorman called me boy and told me to get back to Harlem where I belong. The irony is that the Cotton Club is in Harlem, right in the middle of our neighborhood. It employs our musicians, our waiters, our cooks, and makes its money from our community while refusing to let us in as patrons.”

Mobilizing the Community

Johnson’s words resonated deeply with those present. They recognized that the Cotton Club’s discriminatory practices were not unique but part of a broader pattern of exploitation. Johnson proposed a plan to change the status quo through organized economic pressure.

“We’re going to teach the Cotton Club’s owners that extracting wealth from Harlem while insulting Harlem’s people carries a cost,” he declared. “We’re not going to burn the place down or attack their patrons. Instead, we’ll make operating the Cotton Club so difficult and expensive that they’ll have to either integrate or sell.”

The plan involved several coordinated actions:

-

Labor Organization: Johnson would contact every Black employee of the Cotton Club to participate in coordinated action. Musicians would demand higher wages and better working conditions, threatening to strike if their demands were not met. Waiters and kitchen staff would subtly slow down service to create longer wait times.

Supply Disruptions: Johnson and St. Claire would reach out to suppliers, urging them to stop doing business with the Cotton Club. They would leverage the broader market to threaten suppliers with loss of business if they continued to support a discriminatory establishment.

Community Pressure: Harlem’s churches and community organizations would begin public campaigns criticizing the Cotton Club’s policies, making it a topic of sermons and community meetings. The goal was to create social pressure that made the club’s racism public and indefensible.

Political Complications: Minor legal issues would be created for the Cotton Club, such as health inspections and fire safety reviews, to increase operational costs and divert management’s attention.

Economic Competition: Johnson and St. Claire would invest in alternative venues that welcomed Black patrons, providing competition for the Cotton Club and reducing its reliance on Black talent and labor.

The Campaign Begins

The campaign against the Cotton Club began on September 23, 1935, when Duke Ellington, the club’s biggest draw, announced demands for a 50% increase in his band’s compensation and improved working conditions. When management refused, Ellington threatened to leave for better offers elsewhere, leveraging the offers Johnson and St. Claire had provided.

Simultaneously, problems began to plague the Cotton Club’s operations. Kitchen staff worked more slowly, waiters made mistakes, and suppliers experienced delivery issues. By the second week, the club’s management was struggling with problems they couldn’t identify, leading to increased labor costs and declining customer satisfaction.

Duke Ellington’s threat to leave loomed over the club, and the management realized that they were losing control. The pressure was mounting, and the once-comfortable establishment now faced a serious challenge.

The Negotiation

After weeks of escalating issues, Cotton Club owner Oni Madden received a message to meet with Theodore Green. Madden assumed this was a negotiation, but he was unprepared for the reality of the situation. Green explained that the operational difficulties were a coordinated response to the club’s discriminatory policy.

Madden’s anger flared, but Green calmly pointed out that retaliation against Johnson would only escalate the situation. Madden understood that Johnson had built relationships and power in Harlem that made him nearly untouchable. The threat was clear: if Madden attempted violence, he would only provoke a stronger response.

“What exactly are you demanding?” Madden asked, recognizing the need for negotiation rather than violence. Green presented a proposed announcement that would change the Cotton Club’s admission policy, allowing Black patrons to enter and be served.

After hours of negotiation, Madden reluctantly agreed to the terms. On October 15, 1935, he publicly announced that the Cotton Club would welcome patrons regardless of race, marking a significant victory for Johnson and the Harlem community.

The Impact of Integration

The integration of the Cotton Club sent shockwaves through Harlem. If the most famous whites-only establishment could be forced to change, then other discriminatory venues could be challenged as well. Over the following months, Johnson and his coalition applied similar pressure to other establishments, gradually dismantling the barriers that had long kept Black patrons out.

Johnson’s campaign demonstrated the power of organized economic pressure. It showed that collective action could force change where moral appeals and legal challenges had failed. The methods he pioneered—combining labor organizing, community mobilization, and targeted economic pressure—would influence civil rights activism for decades.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Change

Bumpy Johnson’s experience at the Cotton Club transformed from a personal insult into a catalyst for widespread social change. His decision to respond strategically, rather than with violence, established a precedent for how economic power could be wielded to challenge systemic racism.

The doorman who had insulted Johnson likely never understood the significance of his words. Yet, that moment of humiliation sparked a movement that reshaped Harlem’s entertainment landscape. Johnson’s legacy endures as a reminder that power is not solely about brute force but can be claimed through intelligence, organization, and a commitment to justice.

In the end, the Cotton Club’s integration was not just a victory for one man but a triumph for an entire community, proving that collective action could dismantle the structures of oppression and create a more equitable society.