How One Sailor’s Forbidden Depth-Charge Mod Sank 7 Type VII U-Boats — The Navy Banned It

The depth charges had not been tested at such depths.

Fuses might fail, or detonate early and damage the attacking ship.

Using more charges per attack would mean fewer attacks per patrol.

And above all: changes to weapons were not to be made without official approval.

If deeper settings were necessary, one admiral said, “someone would have devised them already.”

Walker left that meeting knowing he was right—and that nobody with the power to change doctrine was going to help him.

One Ship, One Chance

In December 1941, the Admiralty finally gave him a command at sea: HMS Stork, a humble convoy‑escort sloop in the 36th Escort Group.

It was the sort of ship assigned to officers the system could afford to forget.

Walker treated Stork as a laboratory.

Quietly, without paperwork or permission, he ordered the hydrostatic fuses on his depth charges modified so they could be set far deeper than regulations allowed. Instead of the standard two settings, his charges now covered a ladder of depths—from 100 feet down to over 500.

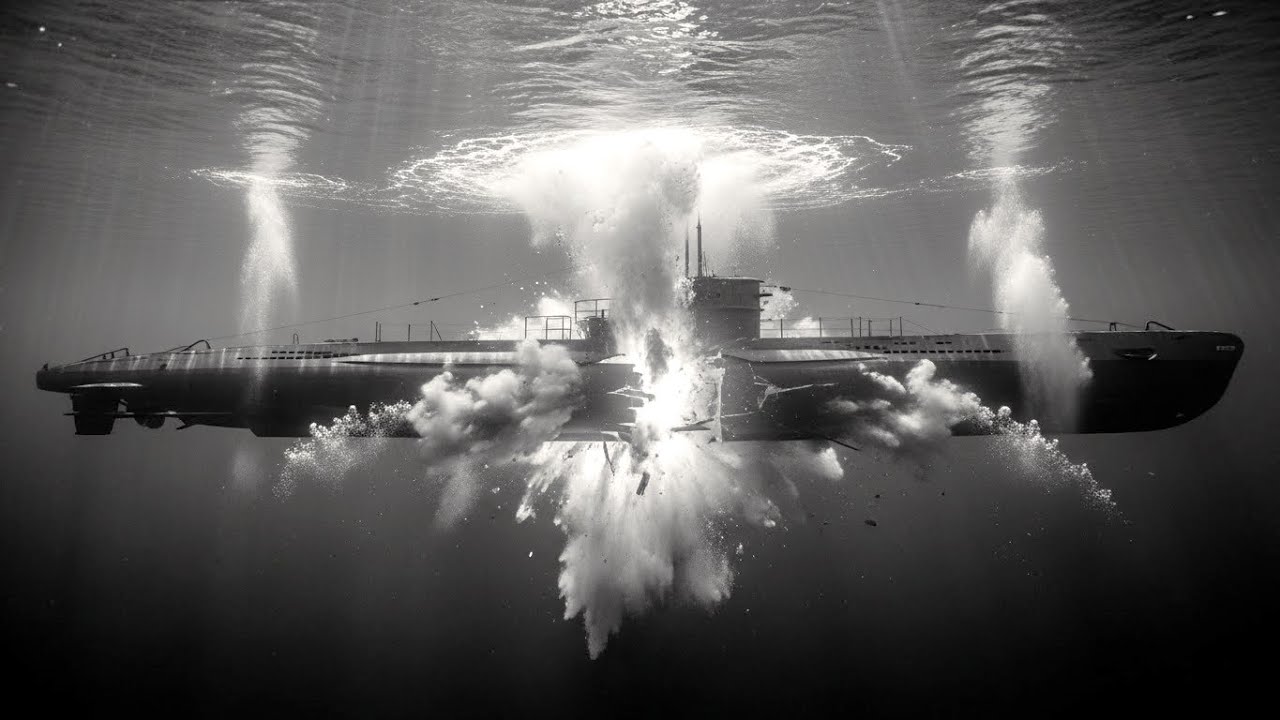

When sonar detected a contact, Stork would drop not three charges at two depths, but five or more at four or five different depths. Instead of a thin horizontal slice through the water, he created a vertical wall of explosions.

The first real test came during convoy HG 76 in December 1941. Stork picked up a U‑boat contact. Walker ordered his new pattern: charges set at 150, 300, 450, and 500 feet.

His executive officer protested. The settings were unofficial. The pattern extravagant.

Walker insisted.

The first explosions went off shallow—the sort of attack U‑boat captains had learned to ignore as they dove. Then a charge detonated at 450 feet, close to the diving submarine. Then another at 500.

Ten minutes later, oil and wreckage surfaced. Sonar had recorded the terrible sound of a pressure hull collapsing.

The kill was confirmed.

Walker went back to his cabin and refined his equations.

Over the next four months, Stork and her group sank four more U‑boats and drove a dozen away from convoys that, under standard doctrine, would have been slaughtered.

The Creeping Attack

Deeper fuses were only half of Walker’s contribution. The other half changed how escorts hunted.

Standard practice was for a single ship to both track the submarine with sonar and carry out the attack. But sonar becomes almost useless the moment a ship charges over the top of its target: propeller noise and the shock of explosions create a blind, noisy void.

Walker’s solution was deceptively simple: split the roles.

One ship, holding station at a distance, would maintain continuous sonar contact, painting a mental picture of the U‑boat’s course and depth.

A second ship would move in slowly and quietly, without sonar, guided only by signals from the tracker. No warning pings. No roaring approach.

When the attacking ship was directly above the submarine, it would drop an entire pattern of depth charges in a tight cluster.

He called it the “creeping attack.”

In March 1942, using this method, his group held a silent U‑boat contact for six hours—a lifetime in submarine warfare—before guiding an escort directly over it. Ten depth charges fell. Minutes later, the U‑boat blew to the surface, mortally wounded, her crew spilling into the waves.

Walker’s logs recorded every detail: contact time, bearing changes, depth estimates, blast settings, results. His success rate climbed. The average escort group was killing U‑boats in 4% of attacks.

Walker’s groups achieved over 9%.

The Admiralty responded in the only way a bureaucracy knows: they summoned him for an inquiry and reprimanded him for unauthorized modifications.

Then, quietly, they promoted him and gave him more ships.

The Day of Three Kills

By early 1944, Walker commanded the Second Support Group: six Black Swan‑class sloops purpose‑built for hunting U‑boats. No convoy to guard. No merchants to distract them. Their job was simple: find submarines and destroy them.

On February 9th, in heavy seas southwest of Iceland, Starling picked up a faint sonar contact at nearly 3,000 yards—beyond what many officers would trust.

Walker went to action stations.

The first target, U‑762, tried to dive deep. Walker executed a textbook creeping attack, with Starling holding contact and Magpie delivering the kill. The U‑boat died at 450 feet.

Before the echoes faded, sonar detected another contact: U‑238. She was experienced, her captain adept at every evasion trick in the book. For eight hours she twisted, dove, and went quiet. Walker matched every move, adjusting patterns, calculating where she would be minutes into the future.

Depth charges set between 300 and 600 feet finally tore her open.

Prisoners came up with the oil.

Then a third contact: U‑734, trying to slip past while the group was engaged. She ran deep, trusting to the ocean below the old 300‑foot safety line.

Walker’s charges detonated at 550 feet.

Hydrophones heard the hull break.

Three U‑boats in fifteen hours.

Over the next ten days, Walker’s group added more kills. By month’s end, the Admiralty had not only lifted its quiet ban on his methods—it had rewritten doctrine to embrace them. Variable depth‑charge settings and creeping attacks became standard practice.

In the first four months of 1944, Allied escorts sank 73 U‑boats, the highest rate of the war. Losses now outpaced Germany’s ability to build replacements. The wolf packs were dying faster than they could form.

The Battle of the Atlantic, once in doubt, tilted decisively.

The Cost of Being Right

Walker did not live to see the end of the war he helped win.

After three relentless years at sea, commanding almost without rest, he died of a stroke in July 1944, exhausted at 48. He was buried in Liverpool, the city whose lifeline he had defended.

He left behind no revolutionary new weapon, no secret technology. He worked with what he had: the same depth charges, the same ships, the same sonar.

What he changed was a single variable—depth settings—and the way those tools were used.

For two years, his key modification was banned as unsafe, untested, unauthorized. Then, when the results could no longer be denied, the Navy made his method mandatory and credited him with more U‑boat kills than any other Allied commander.

The Type VII U‑boat could dive deeper than the old rules anticipated. Walker’s genius was not in discovering that fact, but in accepting it—and daring to adjust everything around it, even when the rulebook said no.

He looked at a 4% success rate and refused to accept it as fate.

In the cold arithmetic of the Atlantic, that refusal helped starve a submarine campaign to death, kept convoys moving, and sustained an island nation long enough to see victory.