When German Engineers Opened a Sherman and Found the Real Secret

In the winter of 1944, a group of German engineers gathered around a wrecked American Sherman tank, their expressions a mix of curiosity and disbelief. The tank, charred and battered, had been dragged from a battlefield in France to a secret test ground in Germany. It was a far cry from the sleek, powerful Panther tanks they had come to admire. As they prepared to dissect this so-called inferior machine, they were driven by one question: what was the secret behind the Sherman’s resilience?

For months, German tank crews had complained about the Sherman’s armor feeling too thin and its gun being unimpressive. Yet, time and again, the Shermans seemed to appear on the battlefield, relentless and undeterred. The engineers sharpened their cutting torches, marked lines on the hull, and prepared to slice the tank open, expecting to uncover some hidden alloy or trick in its construction that explained why this “inferior” machine kept winning battles.

The Initial Encounter

The story of the Sherman’s resilience began months earlier in the chaotic aftermath of the Normandy invasion. Lieutenant Eric Bower, commanding a Panther tank, felt a surge of pride as he surveyed the battlefield. The Panther, with its long barrel and sloped armor, was a formidable machine. On that June morning, as the air still smelled of smoke and salt, Eric spotted three Shermans moving down a French lane.

To Eric, the Shermans looked wrong—too tall, too thin, awkward, as if someone had simply slapped tracks onto a box and called it a tank. His gunner, eager for action, muttered that they were easy prey. But Eric had learned from experience not to underestimate these “boxes.” He ordered his gunner to take aim, and with a swift command, they opened fire.

The first Sherman erupted into flames, smoke pouring from its turret. The second tank halted, reversing in a panic, while the third attempted to ram through the hedgerow. Eric adjusted his aim, firing again and again, losing count of how many Shermans he had destroyed that day. Yet, as the sun set, he couldn’t shake the feeling of dread; every time the smoke cleared, more Shermans appeared on the horizon, seemingly endless.

That night, sitting on the hull of his battered Panther, Eric quietly remarked to his crew, “This war is going to be decided by whoever can build more of those ugly boxes.” Little did he know how close he was to the truth.

The German Engineers’ Perspective

Hundreds of kilometers away, in a complex of brick buildings far from the front lines, Ober engineer Hans Meyer examined the captured Sherman. A veteran of the engineering world, Hans had spent his life in factories, designing safety systems for machines. He had one obsession: efficiency. He believed that if the state was going to invest precious resources into war machinery, it should do so in a way that maximized output.

As he stood before the Sherman, he realized that the Germans had built their tanks like complicated watches—beautiful and precise but ultimately fragile. Hans had seen the production lines for the Panther and the Tiger; they had too many parts, too many machining steps, and too many chances for failure.

He gathered his team of younger engineers and soldiers on temporary assignments. “Today,” he announced, “we find out what is inside the American workhorse.” One of the younger men, a draftsman named Kurt, snorted dismissively, confident that they would find only soft steel and poor welding. But Hans preferred to investigate for himself.

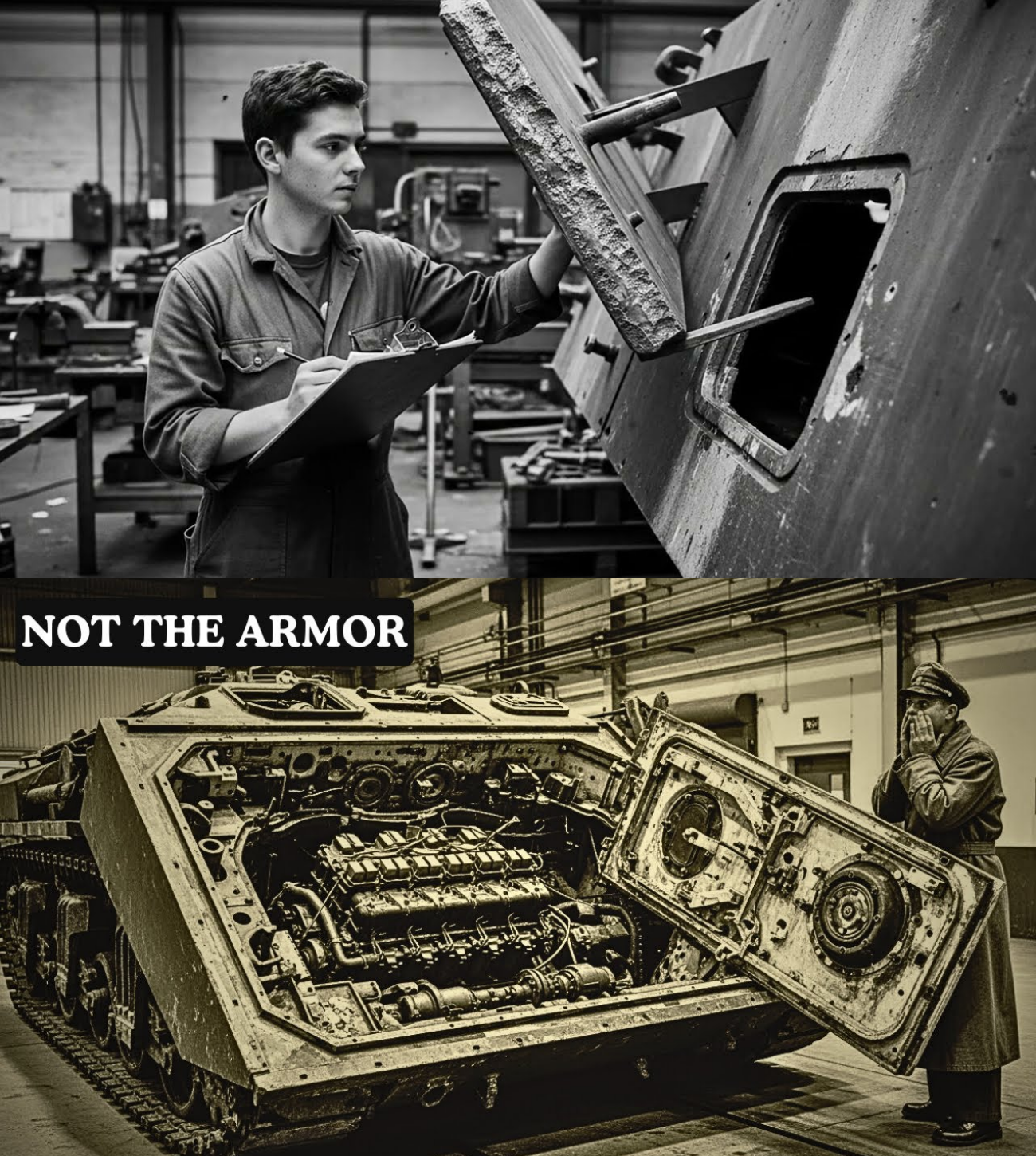

As they began to cut into the tank’s hull, the smell of burned paint and hot steel filled the air. When they pried back the first section of armor, Kurt leaned in, surprised to find that the edges were rougher than he expected. “Cast,” he said, noting the large castings rather than rolled plate like many of their own tanks. Hans smiled, recognizing the implications.

“Big pieces, fewer welds, less machining,” he explained. “That means more tanks per day.” As they continued their examination, Hans noted the simplicity and accessibility of the design. The interior was cramped, but everything was within reach. Controls were where hands wanted to go, and hatches opened cleanly. “This feels like a truck,” he murmured, “a truck you can fight in.”

The Realization

As the team delved deeper into the Sherman’s construction, they discovered that the engine compartment housed an R975 aircraft engine. Kurt was astonished. “Do they have so many they can simply put them in tanks?” he asked. Hans examined the mountings. “Perhaps,” he replied, noting that the standardized interfaces allowed for quick removal as a unit.

“This is not elegant,” he admitted, “but it works again and again on roads, off roads, in the hands of men who learn to maintain it in a few weeks, not a few years.” The use of common fasteners throughout the tank further illustrated the principle of standardization. On German factory walls, tools multiplied like vines, each one perfect for a specific task, while the Sherman utilized versatile tools that could serve multiple purposes.

As days passed, Hans’s team cataloged every part they could, sketching brackets and measuring plate thickness. One evening, as the hall emptied, Hans crawled through the Sherman’s interior one last time. He discovered a small compartment containing a sealed packet of papers—a maintenance manual written in American English.

When Friedrich, a colleague who had spent time in the United States, translated the manual, Hans realized its significance. It was not written like a technical paper; it spoke directly to the reader, offering practical advice for maintenance. “They think their crews are important,” Hans mused. “They talk to them like partners.”

The Presentation

When the day came for Hans to present his findings, he faced a table of officers, some wearing tank badges and others with staff insignia. He began simply, stating that the Sherman’s armor was adequate but not remarkable. An officer frowned, asking why it mattered how it was built.

“Because the armor is not why the tank keeps coming back,” Hans replied. He explained that the Sherman’s engine was powerful enough but not especially efficient. “They did not chase perfection,” he continued. “They chased sufficiency and repeatability.”

A staff officer leaned forward, intrigued. “And the gun?” he asked. Hans acknowledged that the Sherman’s standard 75mm gun was inferior to the German models in penetration. “But they mounted it in a turret that rotates quickly with optics that are good enough,” he added. “They did not chase perfection; they built for practicality.”

The room stiffened as Hans pressed on. “The true secret of this tank is that it was never designed to be the best tank. It was designed to be built by the thousands, maintained by ordinary men, and replaced faster than you can plan a counterattack.” He gestured to the diagram of the Sherman. “It is a cog in a machine that begins in their factories and ends where our fuel and ammunition run out.”

After the meeting, a general approached Hans, asking if they could copy any of the Sherman’s designs. Hans thought carefully. “We can copy the shape of the parts and some assembly methods,” he admitted, “but we cannot copy what makes it truly dangerous.” The general frowned, prompting Hans to elaborate. “The ability to treat a tank not as a precious jewel, but as a consumable tool.”

The Aftermath

As the war dragged on, Hans continued to receive reports from the front lines. One day, he encountered a letter from a tank officer like Eric Bower, detailing engagements with American Shermans. “Destroyed four, knocked out two,” it read, “had to withdraw when we ran low on fuel and ammunition and the next wave arrived.”

Hans imagined the scene: a few Panthers in good positions, a few kills, and then the distant rumble of more Shermans arriving—not better tanks, but simply more of them. He noted the American production statistics, which were terrifying. “A tank like the Sherman,” he scribbled in the margin, “need not be superior to any one of ours. It need only be good enough to do its job and be followed by another and another and another.”

Months later, as the war bled into 1945, Hans found himself beside another wrecked Panther, this time closer to the front. A truck arrived with Lieutenant Eric Bower, who jumped down, limping slightly. “You’re the engineer?” Eric asked. Hans nodded. “I am,” he replied.

Eric looked at the Panther and shook his head. “Beautiful machine,” he said, “until it stops.” Hans smiled sadly. “I’ve heard that before.” Eric gestured toward the horizon. “They keep sending Shermans.” When asked if it was true that he had opened one to find its secrets, Hans confirmed, “I did.”

Eric’s tired eyes searched Hans’s face. “Is it some special steel, a new kind of armor?” Hans shook his head. “The armor is ordinary. The gun is adequate. The engine is loud and thirsty.” He met Eric’s gaze. “The secret is that it was built for the world you’re actually fighting in, not for the world our designers wished existed.”

A Lasting Legacy

The war ended, and Germany lay in ruins. Hans found himself walking through a captured factory years later, now a visitor in a country trying to rebuild. An American adviser stood beside him, noting how they had learned from German designs. Hans chuckled softly, acknowledging that they had also learned from the Sherman.

Reflecting on his experiences, Hans realized that the Sherman was not invincible; it was built for a war with human beings, not idealized drawings. The real weapon was the design philosophy that treated tanks as tools—tools that could be built by the thousands, operated by ordinary men, and sacrificed without collapsing the entire system.

As historians debated the merits of tanks and guns after the war, many overlooked the real secret of the Sherman. It was not about superior firepower or unbeatable armor; it was about the ability to produce and field them in overwhelming numbers. The Sherman’s design philosophy, which prioritized practicality and maintainability, ultimately proved more effective than any individual masterpiece.

In the end, the legacy of the Sherman tank is a testament to the power of quantity, simplicity, and respect for the limitations of real human beings in warfare. It was a machine that could cross oceans, crash through hedgerows, and still find a mechanic who knew how to fix it with minimal tools and a straightforward manual. The German engineers learned that the Sherman was not just another tank; it was a symbol of American industrial might and ingenuity, built to endure and prevail against all odds.