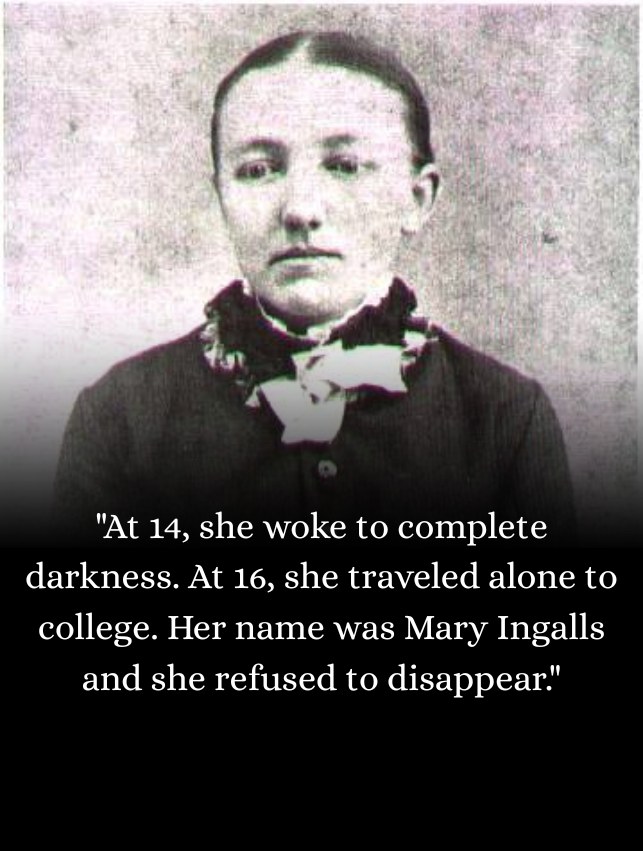

At 14, she woke to complete darkness. At 16, she traveled alone to college. Her name was Mary Ingalls—and she refused to disappear.

Summer, 1879. Dakota Territory.

Mary Ingalls had been burning with fever for weeks. At 14 years old, her small body fought an illness that ravaged her without mercy. Her family gathered around her bed—her father Charles gripping her hand, her mother Caroline pressing cool cloths to her forehead, her younger sister Laura crying softly in the corner.

They prayed she would survive.

Finally, mercifully, the fever broke.

Mary opened her eyes.

But she couldn’t see.

Not her mother’s tear-streaked face. Not her father’s weathered hands. Not Laura’s terrified expression. Not the sunlight streaming through the window.

Nothing.

The illness—likely viral meningoencephalitis, though doctors at the time called it scarlet fever—had stolen Mary’s sight completely and permanently.

At 14 years old, in 1879, on the American frontier, blindness meant something devastating. It meant dependence. Isolation. A drastically limited future. No education. No independence. No life beyond the walls of her family’s home.

This wasn’t the distant past. Thomas Edison had just invented the light bulb that year. Modern America was being born around her. But for a blind girl on the Dakota prairie, the future looked impossibly dark.

Most families would have resigned themselves to caring for their blind daughter forever. Most girls would have accepted a life lived entirely in shadows, defined completely by what they’d lost.

Mary Ingalls refused to disappear.

Her sister Laura became her eyes in those first devastating months. Every morning, Laura sat beside Mary and described everything in painstaking detail—the way wheat moved in the wind, the colors of sunrise painting the sky, the expressions on people’s faces when they spoke.

Laura read to Mary for hours every day, keeping her mind sharp, keeping her connected to a world she could no longer see.

But Mary wanted more than secondhand descriptions.

She wanted her own life back.

In 1881, at just 16 years old, Mary Ingalls made an extraordinary decision: she was leaving home. She would travel hundreds of miles from De Smet, South Dakota, to Vinton, Iowa, to attend the Iowa College for the Blind.

Blind. Alone. On the frontier.

It was almost unthinkable.

Her father Charles had saved every spare penny for years—$150 for annual tuition, an enormous sum for a poor frontier family. Her mother Caroline had sewn Mary’s clothes by hand, every stitch a prayer. Her sisters said goodbye not knowing when they’d see her again.

Mary boarded a train into the unknown, determined to prove that blindness wouldn’t be the end of her story.

At the Iowa College for the Blind, Mary threw herself into learning with fierce determination.

She studied literature, mathematics, science, and history. She learned to read raised print with her fingertips, translating dots and lines into knowledge. She mastered practical skills that seemed impossible for someone who couldn’t see—weaving intricate patterns she could only feel, making brooms with perfect precision, creating needlework so beautiful and exact it seemed to defy the darkness.

She learned German. She memorized entire volumes of poetry. She played the organ, her fingers finding melodies in keys she couldn’t see.

For seven years, Mary proved that a blind girl from a poor frontier family could be educated, cultured, skilled, and independent.

In 1889, she completed her education and returned to De Smet.

But she didn’t return as the helpless girl who had left eight years earlier. She came back as a woman who had built an identity beyond her disability.

Mary never married. In the 1880s, this was often viewed as tragic—a “failed” life for a woman.

But Mary didn’t see it that way.

She lived with her family, yes. But she contributed in countless ways. She sewed clothes with stitches so perfect they looked machine-made. She memorized entire books and recited them from memory to anyone who would listen. She played music that filled their small house with unexpected beauty.

She helped raise her younger sister Grace’s children, telling them stories in the darkness that painted pictures more vivid than sight ever could.

When people saw Mary, they often saw only what she’d lost. But Mary’s family knew better. They saw what she’d built.

In 1924, Mary’s mother Caroline died. Mary was 59 years old—she had long outlived the fragile, sickly girl everyone expected wouldn’t survive to adulthood.

She moved in with her sister Carrie, continuing the quiet, purposeful, dignified life she’d created on her own terms.

On October 20, 1928, Mary Amelia Ingalls died peacefully at age 63 in De Smet, South Dakota.

Most of the world never knew her name.

But her sister Laura never forgot.

Years later, when Laura Ingalls Wilder sat down to write the Little House books that would eventually be read by millions of children around the world, Mary was there on nearly every page.

The gentle older sister. The brave girl who lost her sight but never lost herself. The woman who proved that darkness doesn’t mean disappearance.

Laura made certain the world would remember: Mary Ingalls was not just “the blind sister” in the background of someone else’s more interesting story.

She was a girl who woke up to complete darkness at 14 and spent the next 49 years proving that light doesn’t only enter through your eyes.

She was a woman who lost her sight but absolutely refused to lose her mind, her skills, her independence, or her dignity.

She was a frontier girl who traveled alone to college when most women never left their hometowns.

She was proof that the most extraordinary lives are often the quietest ones—the ones that change not the world, but what the people closest to them believe is possible.

Mary Ingalls never became famous. She never wrote bestselling books or gave inspiring speeches or changed laws or started movements.

But she changed what her family believed a blind girl could become.

She changed what her community thought was possible.

And through her sister’s loving words, she changed what millions of readers came to understand about resilience, courage, and the human capacity to adapt.

She woke up one morning at 14, and the world had disappeared.

So she spent the next 49 years building a new one in the darkness.

And it was beautiful.

Her name was Mary Ingalls.

And she refused to disappear