He’s Been Encountering Mermaids Since the 1970s. What They Told Him About Humanity Will Shock You

The Depths We Cannot See

I am seventy-one years old. For nearly half a century, I have carried a secret in my chest like a stone. My name is Robert Callahan, and I spent forty years as a commercial fisherman, working the cold, blue waters off the coast of Maine. I was an ordinary man. I caught cod and haddock, mended nets, paid taxes, raised two daughters, and kept to myself. But since August 1974, I have known something that doesn’t fit into an ordinary life.

I saw things in the North Atlantic that science says don’t exist. I communicated with beings that have no place in our understanding of marine biology. And I learned truths about why they hide from us—truths that made me question everything I thought I knew about humanity’s place in the world.

I never wanted to tell this story. For decades, I convinced myself that silence was the responsible choice. Who would believe me? What good would it do? But six months ago, my doctor found a mass in my pancreas. Stage four. They gave me a year, maybe less. Dying with this knowledge felt wrong. Not because I need anyone to believe me, but because somewhere in the deep ocean, they are still out there, watching us, hoping we might prove them wrong about what kind of species we are.

This is what happened. This is what I know.

August 12th, 1974. I was twenty-four, working my third season on the Mary Catherine, a forty-two-foot trawler I’d bought with money saved from years on other men’s boats. She was rusty but reliable, her engine solid, her hull sturdy against rough seas. That morning, I left Portland Harbor at 4 a.m., heading sixty miles offshore for cod. The forecast called for calm seas and light winds. By 5:30, I was alone on the water, the nearest vessel at least ten miles away.

I preferred working solo. Smaller catches, but no crew to pay, no complications. I hauled nets as the sun broke the horizon, turning the water from black to gray to deep blue. The air was cool, the sea flat enough to see my reflection between the swells.

Two hours passed. I saw something surface thirty yards off the starboard side. At first, I thought it was a seal. We saw them often enough. But seals don’t float upright. I cut the engine and reached for my binoculars.

The figure was closer now, drifting with the current. Dark hair, pale shoulders, arms moving slowly in the water. A swimmer? Maybe someone lost overboard. I moved to the rail and called out. “Hey! Are you hurt?”

The figure turned. I saw a face—human features, but not quite right. The eyes were larger, wider apart. The nose was flat, the mouth wide. She stayed upright in the water, effortlessly, no sign of treading. I leaned over the rail. “I’m coming to get you. Hold on.”

I started the engine, maneuvering the boat carefully. She watched me, unafraid. As I got closer, I saw her skin—pale, with a faint blue-gray tint. Her hair floated around her shoulders, each strand moving independently, not clumped like human hair in water. Her shoulders were narrow but muscular. When she lifted her arms, I saw webbing between her fingers.

She dove. Not like a person, but like a seal—one smooth motion. Where legs should have been, I saw a tail, five feet long, moving with powerful horizontal strokes. The last thing I saw before she disappeared was the tail flukes, catching the light.

I stood at the rail, hands shaking. My mind raced for explanations—a costume, a hoax, a hallucination. But the way she moved, the intelligence in her eyes, none of it fit. I didn’t call the Coast Guard. What would I say? I saw a woman with a tail. They’d think I was crazy.

I didn’t fish anymore that day. I just stared at the spot where she vanished.

For three weeks, I avoided that spot. I fished closer to shore, told myself I didn’t want to see her again, but the truth was I was afraid to confirm what I’d seen. But on September 4th, needing a good catch, I returned.

The weather was rougher. As I pulled in my third net, I felt unusual resistance. Something big was caught. I worked the winch slowly. The net broke the surface, and there she was—tangled, barely moving. Her skin was gray-blue, her hair dark, her tail wrapped tight in the mesh. Blood streaked her skin.

She was dying. I grabbed my filleting knife and sawed at the net. It took fifteen minutes to free her arms and tail. She watched me through half-closed eyes, her breathing shallow. I talked to her as I worked. “Hold on. Almost there.”

When I finally cut the last strand, she slid into the water, gasping for air. She surfaced, panic in her eyes. I stripped off my shirt and boots, tied a rope around my waist, and went in after her. The water was cold. I got my arm under her shoulders, keeping her head above water. She flinched, tried to pull away, but was too weak.

We stayed like that for two hours. My arms went numb, my legs cramped, but slowly her color improved. Her breathing steadied. She started making sounds—not words, but vocalizations, low notes with a rhythm. I felt them in my chest. She made a sound, paused, made another. It was deliberate, communicative.

Around noon, she flexed her tail and pulled away gently. She swam in a circle, testing her strength, then returned. She reached out and touched my hand, her skin cool and smooth. She held it for five seconds, made a soft sound, then dove.

I climbed back onto the boat, shivering. That night, I couldn’t sleep, thinking about the way she’d looked at me, the way she’d touched my hand. I’d saved her life, and she’d known it.

She returned the next morning. For an hour, we just watched each other. I drew a fish in my notebook and showed her. She made a sound—higher pitched. I drew a stick figure and pointed at myself. She dove, then surfaced with a piece of kelp. She pointed at herself and made a three-note sound. I tried to repeat it; she corrected me.

That became our routine. Every morning for a week, I went to the same spot. She brought shells, coral, even a brass compass from the ocean floor. I brought apples and bread; she ate the apples, rejected the bread. Our communication was simple—gestures for yes, no, danger, food.

By November, I saw others in the distance. They never came close, but watched. She made sounds to them, and they answered. She was showing them I could be trusted.

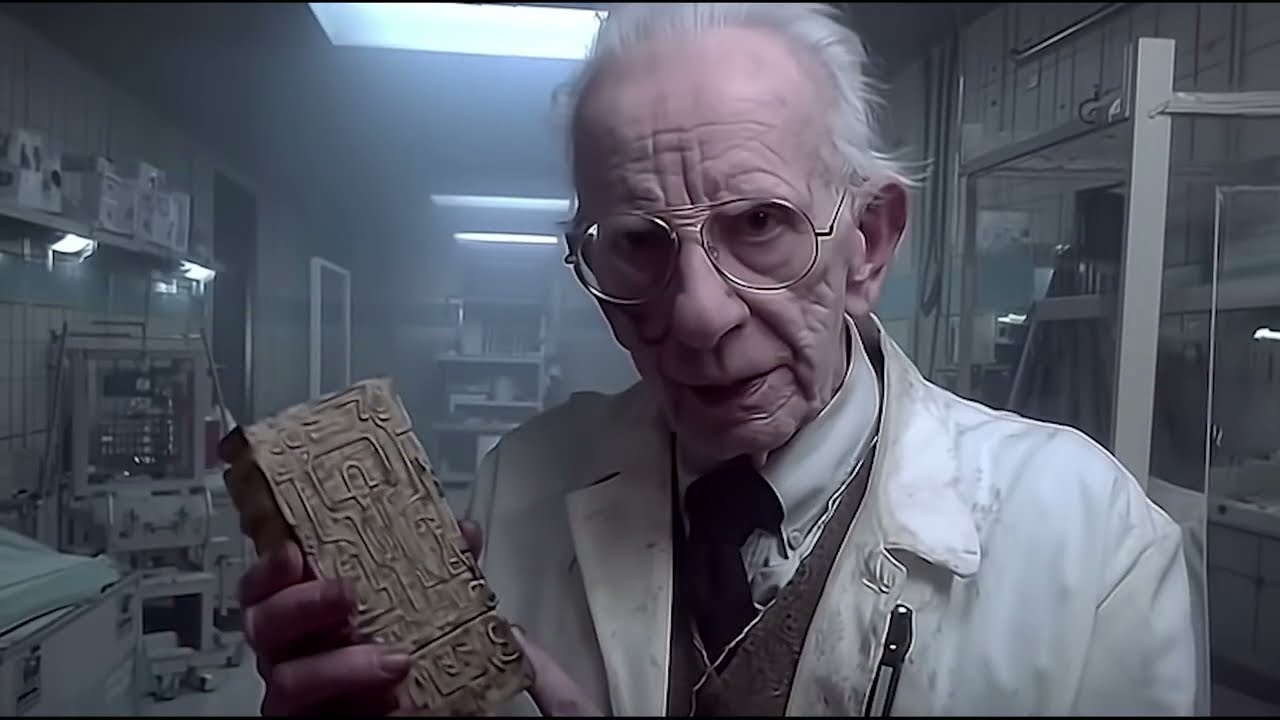

She showed me ruins underwater—carved stones, pottery, metal tools. Her people had history, culture, language. I dove with her, documenting everything. She gave me a carved stone, covered in symbols. “Keep,” she gestured.

She showed me drawings—her people hunted by humans, then fleeing to the deep. She showed me nets, bodies caught and killed. I understood why they hid. Not because they were afraid, but because they’d watched us for thousands of years. They’d seen what we did to anything different.

In 1982, she showed up wounded—propeller strikes. I cleaned her wounds, treated her as best I could. She gestured: her people were leaving, going deeper, away from boats and nets. She said goodbye. I watched her group—adults and young—migrate to the deep.

Three years passed before I saw her again. She was older, slower. She brought me a piece of white coral, carved with symbols. “Keep,” she gestured. We said goodbye, knowing it was the last time.

For thirty-nine years, I kept the coral locked in a safe. I never showed it to anyone. I kept my notebooks, my sketches, my memories. I protected her secret because I knew what would happen if I revealed it—scientists, governments, trophy hunters. They would be found, studied, captured, destroyed.

Now I am dying. I leave the coral to my granddaughter, Emma, who studies marine biology. I hope she will protect them. They don’t need to be discovered. They need us to be better.

She wasn’t asking for help. She was showing me what we were doing, hoping one human understanding might make a difference.

I have six months left. I have kept this secret for fifty years. Now I am breaking my silence—not for attention, but because somewhere in the deep, they are still watching, waiting to see if we can be better than our history suggests.

For their sake—and for ours—I hope we can.