When Marvin “Bumpy” Ellison told the story years later, people always thought he was exaggerating the part about the clouds.

But he remembered it clearly: the sky over Harbor Heights had been perfectly blue—polished, expensive blue, the kind that made the glass towers shine—until about ten minutes after Victor Langford called his mother the N‑word. Then a long, dark cloud had slipped in from the west like a curtain being drawn.

“It’s funny,” Bumpy would say. “The day turned ugly about the same time he did.”

1. Harbor Heights

Harbor Heights was the kind of New England coastal town that pretended it didn’t have a past. The old wharfhouses had been turned into galleries and artisanal bakeries; the warehouses became lofts where tech consultants with money and yoga instructors without it both drank the same overpriced coffee.

On the hill that watched over the bay stood the Langford estate: three acres of manicured arrogance.

Victor Langford III liked to say he’d “rebuilt” the family fortune. The truth was, he’d inherited more money than most people would see in ten lifetimes and managed not to crash it entirely. He owned commercial real estate in three states, a chain of “upscale sports bars” that treated staff like replaceable napkins, and a small PR firm whose only real job was making him seem less despicable than he actually was.

He also owned the building at the corner of Delaney and 5th.

Bumpy’s mother cleaned it.

2. Bumpy and His Mother

Marvin got the nickname “Bumpy” as a kid; a cousin threw a rock once, and he came home with a lump on his forehead the size of a walnut. The name stuck even after the bump melted away. By the time he was in his late twenties, working two jobs and helping his mom with her English classes at night, nobody in Harbor Heights remembered his actual first name.

His mother, Lorraine, was one of those women whose strength got mistaken for stubbornness until you needed it. She’d moved to Harbor Heights when Bumpy was ten, cleaned houses, then offices, then entire buildings.

“Money doesn’t make you better than anyone,” she would say as she scrubbed other people’s marble counters. “It just makes you louder. Don’t confuse volume with value, baby.”

She’d tucked away enough to send Bumpy to community college. He studied accounting by day and worked nights at a small bodega on Delaney. On Fridays, he walked his mother home from the Langford building when her cleaning shift ended.

“It ain’t safe, you out here by yourself after dark,” he’d say, though he knew she could swing a mop handle like a staff if she had to.

This Friday was no different—until it was.

3. The Encounter

The lobby of the Langford building was all marble, glass, and fake plants. It smelled like lemon cleaner and money.

Lorraine had just finished up on the seventh floor and was wheeling her cart toward the service elevator when the main elevator doors slid open with a soft ding.

Victor Langford stepped out, pressed shirt open at the collar, cufflinks glinting. Beside him walked a woman in high heels and an expensive dress, half his age and clearly amused by something he’d just said.

“…and the tenants whine about ‘working conditions’ like they don’t sign the leases,” he was saying. “People forget their place these days.”

His eyes flicked toward Lorraine, then past her, then back again, as if he’d just realized she was part of the environment and not the furniture.

“You,” he said, lifting his chin the way some people pointed. “You missed a spot in the men’s room on five. Smelled like cheap cologne and piss.”

Lorraine stopped, straightened her back, and turned fully to face him.

“The men’s room on five was spotless when I left it, Mr. Langford,” she said. Her voice was calm, but there was a steel thread in it. “If it smells bad now, that’s on the men, not the cleaner.”

The woman with Langford smirked behind her hand.

Langford’s face tightened.

“Attitude doesn’t come with your pay, sweetheart,” he said.

Lorraine’s jaw worked.

“My contract is with your company,” she said. “Not with your ego.”

The woman’s smirk vanished. Langford flushed, the color rising under his tan like a warning light.

“Watch your mouth,” he snapped. “You people are lucky to have jobs at all.”

Lorraine blinked slowly.

“You people?” she repeated.

He made a vague, circular gesture that somehow encompassed her, the cart, and several centuries of ugliness.

“Cleaners. Help. Whatever,” he said. “Don’t try to play stupid with me, girl.”

She wasn’t a girl. She was fifty-six. She’d buried a husband, raised a son, and survived more than Langford could imagine.

“That’s Mrs. Ellison to you,” she said quietly.

He barked a laugh.

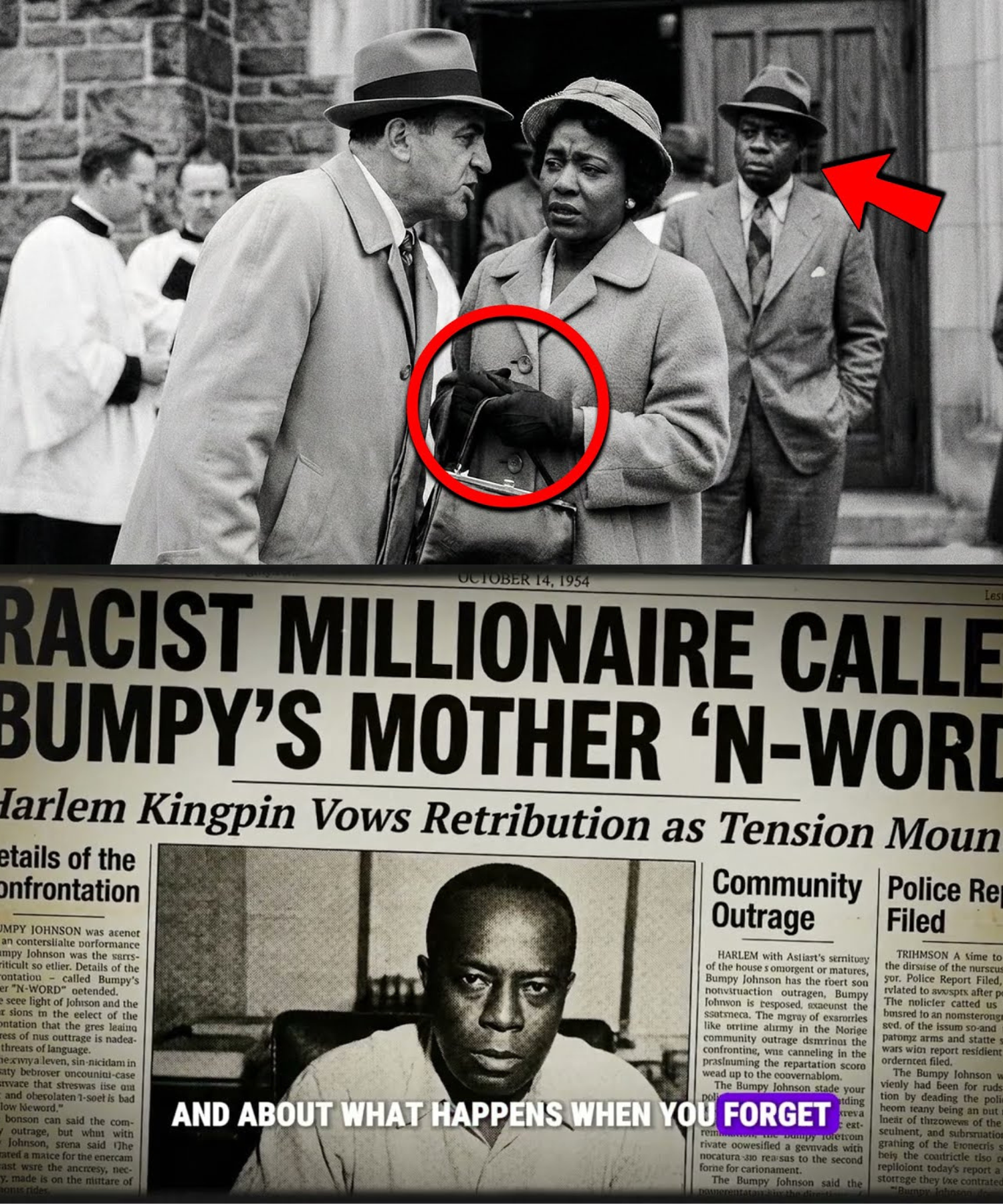

“Mrs. Ellison,” he sneered. “Or should I say Mrs. N—”

The slur slid out of his mouth like something he’d been waiting to use, something worn smooth from practice. He hit the hard R, like he enjoyed the sound of it.

The lobby froze.

The woman beside him stiffened. Even the air seemed to recoil.

Lorraine’s hand tightened on the cart handle until her knuckles went white. For a moment, she just looked at him, eyes level, all the way through.

Then she spoke in a voice that wasn’t loud, but carried.

“Don’t you ever call me that again,” she said. “You don’t get to put that word in your mouth and aim it at me. Not after everything my people bled for so you could stand up here acting like you built the building your granddaddy bought.”

Langford stepped closer, close enough that she could smell the expensive whiskey on his breath.

“I’ll call you whatever I please,” he hissed. “And if you don’t like it, you can pack your little bucket and go scrub some other toilets. You think you’re the only N— willing to wipe my floors?”

The second time he said it, he said it louder.

That was when Bumpy walked in.

He’d pushed through the revolving door with a grin already forming—ready with some joke about his mom “outcleaning” the whole building—and stopped dead three steps in.

He saw Langford’s posture. His mother’s face. The way the woman beside Langford was staring studiously at the floor.

He didn’t hear the slur; he felt it.

It vibrated in the air, ugly and heavy.

“Mom?” he said.

Lorraine turned.

Her eyes were brighter than they’d been when she left home that morning, but her voice was steady.

“It’s all right, baby,” she said. “Mr. Langford was just leaving.”

Langford’s gaze flicked to Bumpy and sharpened.

“Oh look,” he said. “The cavalry. You her boy? Makes sense. You got the same sad, lazy look. Let me guess—you on my payroll too? Security? Maintenance? Or just another N— dragging his feet on my marble?”

This time, he said it clearly enough for everyone to hear.

The receptionist in the corner, a young white guy named Evan, went very still. He’d heard rumors about Langford’s mouth, but rumors had just become evidence.

Bumpy’s first instinct was to swing.

His fists curled tight. His heart hammered in his throat. Every story he’d been fed since he was a child—about how to “handle” racism, how to “de-escalate,” how to “pick your battles”—collided with a raw, animal urge to drop this man where he stood.

Lorraine saw it all flicker across her son’s face.

She stepped between them, palm pressed against Bumpy’s chest.

“Marvin,” she said, using his given name like a command. “No.”

“He called you—” Bumpy began, voice ragged.

“I know what he called me,” she said. “I been called worse by better men. You hit him, you go to jail. He gets to cry victim. Again.”

Langford laughed, a short, ugly sound.

“Listen to your mama, boy,” he said. “She’s smart enough to know where she belongs, even if she forgets sometimes.”

Bumpy looked at him over his mother’s shoulder.

In that instant, he made a decision.

He unclenched his hands.

“Yeah,” he said softly. “She knows exactly where she belongs.”

He looked around the lobby.

At Evan, eyes wide and phone halfway out of his pocket.

At the security camera bubble in the ceiling.

At the laminated sheet on the wall outlining the building’s “Harassment-Free Workplace Policy,” with its generic clip-art handshake.

Then he smiled.

“But I think you are about to find out where you belong,” he said.

Langford scoffed.

“And where’s that?” he said.

“Out,” Bumpy said. “Way out.”

It sounded like bravado.

It wasn’t.

Because Bumpy had two things Langford didn’t know about:

An accountant’s brain.

And a long memory.

4. The Plan

“Marvin, let it go,” Lorraine said on the walk home. “The world is full of men like him. You can’t pick up every piece of broken glass, you’ll cut yourself to ribbons.”

The streetlights painted her face in alternating bands of gold and shadow.

Bumpy walked beside her, hands in his pockets.

“I’m not going to hit him,” he said. “You saw me. I didn’t. You raised me better than that.”

“I know,” she said. “That’s what scares me. You smiled instead.”

He huffed a small laugh.

“You ever wonder how a man like that keeps owning buildings in a town like this?” he asked. “Harbor Heights has a diversity council, a ‘Racial Equity Council,’ a Pride parade, a whole mural about inclusion down on Bay Street. But up on the hill? That man uses my mom’s face as target practice for 400 years of hate.”

“You think the mural’s going to stop him?” Lorraine asked.

“No,” Bumpy said. “But something else will.”

He’d been working at Harbor Heights Community Bank for a little over a year now. Back office, entry-level: reconciling invoices, checking for irregularities in commercial accounts, flagging unusual patterns for senior analysts.

He’d seen the name Langford Holdings, LLC more times than he could count.

“I can’t just go digging in his account,” he said out loud, more to himself than to his mother. “That’s illegal as hell.”

“That’s right,” she said. “We don’t do illegal.”

“But there are things you can do,” he said slowly. “Things that are just… shining a light where nobody wants one. That policy in the lobby? The anti-harassment one? It’s not just for show. He signed off on that when he registered the building with the city.”

“You think the city cares?” Lorraine asked. “He probably writes half those people their campaign checks.”

“Maybe,” Bumpy said. “But the city doesn’t like lawsuits. Or viral videos. Or losing tax breaks because some racist millionaire gets exposed calling his employees the N‑word in the lobby.”

She looked at him sideways.

“You have that look,” she said.

“What look?” he asked.

“The ‘I’m about to read the fine print and ruin a man’s whole week’ look,” she said.

He smiled.

“More than his week, Mom,” he said. “Give me eight hours.”

5. Evidence

The first thing he did was call Evan.

“Man, I don’t want to get fired,” Evan said, voice shaking enough that Bumpy could hear it through the phone. “I need this job. Rent here is crazy.”

“You won’t,” Bumpy said. “Not if we do this right. Did you record any of that?”

There was a pause.

“Maybe,” Evan said. “I mean… I might have hit the Voice Memo button on my phone when Mr. Langford started raising his tone. Company protocol says to document ‘escalated interactions,’ right?”

“Smart,” Bumpy said. “Send it to me. And check this: did you see which cameras were pointed at the lobby?”

“Yeah,” Evan said. “We have three. One at the entrance, one above my desk, one facing the elevators. They feed into the security office in the basement. The guard’s cool—he hates Mr. Langford more than we do. Says he treats him like ‘rent-a-cop furniture.’”

“Then we start with him,” Bumpy said.

Next, he sat at his tiny kitchen table with his laptop and a yellow legal pad, writing out:

What happened.

- (Short version, unemotional, just times and words.)

Who saw it.

- (Evan. The security guard, if he’d been watching the monitors. The woman with Langford—if they could find her.)

Where it violated policy and law.

- (Company harassment rules. City anti-discrimination ordinances. Possibly state labor law.)

He wasn’t a lawyer.

But he knew numbers, patterns, and how money moved when it got scared.

He found the city’s online portal and pulled up the public records on Langford’s building. It listed:

Owner: Langford Holdings, LLC

Tax abatement status: Active, subject to review annually based on compliance with Fair Workplace Certification.

There it was.

Fair Workplace Certification.

A little, bureaucratic lever.

He tugged.

6. The Switch

Saturday morning, Bumpy went to the security office in the basement of the Langford building with a box of doughnuts under his arm.

Officer Kendrick Willis eyed the box, then Bumpy, then the box again.

“You here to bribe me, kid?” he asked.

“Depends,” Bumpy said. “You take bribes in glazed or chocolate?”

Willis snorted.

“Sit down,” he said. “I saw what went down yesterday. Hell of a mouth on that man.”

“So you did see it?” Bumpy asked.

“Heard it too,” Willis said. “Had the lobby cam up for a noise complaint on five. Figured I might need to go up. But the old lady handled herself.”

He smiled, respect in the tilt of it.

“You still got the footage?” Bumpy asked.

Willis’s smile faded.

“Those feeds overwrite every 48 hours,” he said. “Company policy. Unless someone flags an incident and saves the clip to the server. Why?”

“I want to flag it,” Bumpy said. “Officially.”

Willis raised an eyebrow.

“Your mom okay with that?” he asked.

“She taught me to mop floors and stand up straight,” Bumpy said. “I think she’ll survive me filling out a form.”

He slid the doughnut box closer.

“Look,” he said. “I’m not asking you to falsify anything. Just to tag the relevant time frame as ‘incident—potential harassment,’ so it gets preserved. It’s what you’d do if two tenants got into a fistfight, right?”

Willis chewed slowly on a sugar ring.

“Right,” he said. “And you know those clips are time-stamped and watermarked. No way to edit without leaving fingerprints.”

“Good,” Bumpy said. “I want them as is.”

Willis sighed, pushed his chair back, and turned to the beige tower that passed for the building’s security server.

“You’re lucky I don’t like my boss either,” he grumbled. “Give me the time—when did it happen?”

“Yesterday, 5:42 p.m. to 5:48 p.m.,” Bumpy said without hesitation.

Willis shot him a look.

“You got a clock in your head, or you just obsessive?” he asked.

“Both,” Bumpy said.

Willis typed, clicked, and a grainy video appeared on his screen: the lobby, viewed from the ceiling cam.

They watched it in silence.

Langford’s body language was clear even without sound: the sharp lean-in, the dismissive gesture, the way he crowded Lorraine’s space. You didn’t need audio to see who held the power and who refused to be crushed by it.

“Damn,” Willis said softly as the moment played out. “Okay. I’m tagging this. ‘Harassment incident, possible policy violation.’ That’ll save it to the main server. Building management has access. So does the corporate HR office.”

“And the city?” Bumpy asked.

Willis hesitated.

“They can request it,” he said. “If somebody makes enough noise.”

Bumpy smiled slowly.

“Then let’s make some.”

7. The Pressure Points

He spent the afternoon in the public library, because his own Wi‑Fi was too slow and the librarian didn’t ask questions.

He sent three emails:

To Langford Holdings HR

- , subject line:

Formal Complaint—Racial Harassment at 17 Delaney Street

- .

He kept it professional:

Described the incident.

Attached the audio file Evan had sent him.

Named witnesses.

Cited specific lines from the company’s policy about “zero tolerance for discriminatory language.”

He cc’d the generic “info@langfordholdings” address, knowing some assistant would panic-read anything with the word harassment in it.

To the City Fair Workplace Office, subject: Potential Fair Workplace Certification Violation—Langford Holdings.

He attached the same audio, summarized the complaint, and politely asked whether tax abatements could be reviewed when a building owner was recorded using racial slurs against staff in a certified “harassment-free” environment.

To a local journalist, subject: Tip: Racist outburst from Harbor Heights developer caught on camera.

He didn’t send the audio to her.

Not yet.

He just mentioned that there was footage, that a formal complaint had been filed, and that “multiple sources” could confirm the incident.

He didn’t have multiple sources yet.

But he had a feeling that once one domino fell, others would wobble.

Then he did the most important thing:

He went home, made his mother tea, and told her everything.

“You filed a complaint?” she asked, astonished. “You called the city?”

“Yes,” he said.

“You sent an email to a journalist?” she repeated.

“Yes,” he said.

Lorraine sat down hard.

“You just declared war on a man who owns half this town,” she said.

He sat beside her.

“You raised me to count, to read, to understand how power works,” he said. “This is how we fight when we’re outgunned. We use paper. We use policy. We use the fact that men like him care more about their image than anything.”

She looked at him for a long moment.

“You sure you’re ready for whatever comes?” she asked.

“No,” he admitted. “But I’m sure I’m more ready than he thinks.”

8. Eight Hours

The timeline went something like this:

08:02 a.m.

Langford’s assistant opened her email and saw Bumpy’s subject line. Her stomach dropped. She forwarded it to Corporate HR with the subject: URGENT—Please Advise.

08:17 a.m.

Corporate HR director, already on edge because of an upcoming compliance audit, opened the email, put on headphones, and listened to the audio.

She stopped it halfway through.

She replayed it, making sure she’d heard correctly.

She had.

She forwarded it to the company’s legal counsel with a single sentence: We have a problem.

09:05 a.m.

At City Hall, a Fair Workplace officer saw Bumpy’s email, recognized Langford’s name, and forwarded it to their supervisor with the note: If this is legit, we may need to revisit their certification.

09:42 a.m.

The local journalist, Lena Chavez, read Bumpy’s tip. She’d been chasing a story on Harbor Heights’ glossy surface versus its rotting core for months. A racist outburst from one of its “golden boys” was exactly the crack she’d been looking for.

She replied: Can we talk on background?

10:03 a.m.

Corporate Legal called Langford.

He was on the golf course.

“Victor,” the lawyer said in a tone that suggested he’d rather be doing anything else. “We received a complaint. And audio.”

“A complaint?” Langford said, annoyed. “I get complaints every week. Tell them to wipe their tears with their paychecks.”

“Not like this,” the lawyer said grimly. “You were recorded using a racial slur toward an employee. In the building. In the lobby.”

Langford swung, missed a shot, and cursed.

“That woman?” he said. “The cleaner? She’s lucky I didn’t fire her on the spot. These people are always stirring up drama.”

“‘These people,’” the lawyer repeated slowly. “Victor, I need you to understand: we are not in a forgiving environment right now. The city ties our tax benefits to Fair Workplace compliance. If they see this and decide we’re in violation, we’re talking millions over the next decade. Not to mention reputational damage, lawsuits…”

“Lawsuits,” Langford said. “From a janitor?”

“From a human being with a recording,” the lawyer said, losing patience. “And we have another problem. The complaint cc’d the city and—apparently—a journalist. If this goes public before we get ahead of it, we’re done.”

“So what do you want me to do?” Langford snapped. “Apologize?”

“Yes,” the lawyer said. “Immediately. In writing. To her. To the staff. And then you need to lay low while we do damage control.”

“I’m not apologizing to some N—” Langford began.

“Do not say that word again,” the lawyer cut in, voice like ice. “Not to me. Not to anyone. Especially not on a recorded line. Do you understand?”

There was a long pause.

“Fine,” Langford said finally. “Send me whatever your PR monkeys write. I’ll sign it.”

10:37 a.m.

The Fair Workplace supervisor requested the security footage from the incident time frame from the Langford building.

Officer Willis, seeing the request, smiled into his doughnut and uploaded the clip without a word.

11:12 a.m.

Lena, the journalist, met Bumpy at a café on Bay Street.

He showed her the audio.

He didn’t let her keep a copy.

“Not yet,” he said. “Let’s see what he does first. I’m not trying to be your grenade. I’m trying to be the reason they take the pin out of their own.”

She laughed despite herself.

“You know how this works,” she said. “If I publish, I’ll need the file.”

“You’ll get it,” he said. “But if there’s even a chance he’ll do the stupid thing first, I want to give him the rope.”

“The stupid thing?” she asked.

“Try to bury it,” Bumpy said. “Or bury us.”

12:01 p.m.

Langford stormed into his office, flung his phone on the desk, and called his assistant.

“Get me the cleaning company,” he barked. “I want that woman out of my building today.”

His assistant swallowed.

“There’s… an issue with that,” she said. “Legal advised we don’t take any retaliatory action. It would make things worse.”

“I am legal,” Langford snapped.

“You’re not,” she said carefully. “They are. And they said if we fire her now, it’s textbook retaliation. The city will eat us alive.”

He glared at her.

“How long have you worked here?” he asked.

“Six years,” she said.

“You like your job?” he asked.

“I like having a job,” she said.

“Then don’t tell me what I can’t do in my own company,” he said.

He grabbed the phone himself, dialed the cleaning company’s number off a laminated card, and when the manager answered, launched into a tirade.

“I want that woman—Lorraine whatever—gone,” he snarled. “She mouthed off to me in my own building. She’s making up stories now. Fire her, or I find another company.”

The manager, who’d already received a heads-up from his HR about the complaint, held the phone away from his ear and stared at it like it was a snake.

“Mr. Langford,” he said carefully. “We’ve been instructed not to take any action until the investigation is complete. If we terminate her now, it exposes us to liability.”

“You work for me,” Langford said. “You do what I say.”

“With respect, sir,” the manager said, “we work with you. And we also work with the law. If you insist on retaliation, please put that in an email so we have a paper trail.”

He’d learned that trick in a three-hour training and had never expected to use it.

Langford sputtered, then hung up.

01:26 p.m.

The Fair Workplace office, having watched the footage and listened to the audio, convened an emergency review board.

By now, they’d also received an anonymous tip that the owner of 17 Delaney was “leaning on” a contractor to fire an employee who’d lodged a complaint.

Retaliation.

They didn’t like that word.

02:03 p.m.

Langford’s lawyer sent him a memo: Do NOT contact Ms. Ellison or any witnesses. Do NOT attempt to influence their employment. Any appearance of retaliation will jeopardize our position.

Langford crumpled the memo and threw it at the wastebasket.

He missed.

02:47 p.m.

Lena received an email from a city contact she’d cultivated for years.

Off the record: you might want to look into Langford’s Fair Workplace status. There was an incident. Audio, video. Could be big.

She smiled.

Her story was writing itself.

03:12 p.m.

Bumpy went with his mother to her afternoon shift—not at the Langford building, but at a smaller office a few blocks away.

A representative from the cleaning company met them there, wringing his hands.

“Ms. Ellison,” he said. “We received a call. From Mr. Langford. He wanted us to fire you.”

“I figured,” she said.

“We’re not going to,” he rushed to add. “Our HR advised against it. We’re, uh, cooperating with the investigation. And they suggested we transfer you off that account. For your safety.”

“For my safety,” she repeated slowly.

“Yes,” he said. “Also, the city reached out. They might contact you directly. They, uh, have the footage.”

Lorraine glanced at her son.

He just nodded once.

“Thank you for telling me,” she said. “I’ll talk to the city.”

The representative hesitated.

“There’s more,” he said. “Off the record. I heard from one of the other cleaning supervisors. She said… this isn’t the first time he’s used language like that.”

“Not surprised,” Bumpy said.

“But it might be the first time someone caught it on camera,” the rep added.

9. Begging

It didn’t happen all at once.

Reputations never do.

They fray.

They drip.

Then, sometimes, they snap.

Day 2

Lena published her first story: Developer Accused of Racial Slur in Downtown Building. She quoted “sources” who’d seen the footage. She didn’t name Lorraine or Bumpy, but she named Langford.

She mentioned the tax abatements.

She mentioned the Fair Workplace review.

The story got modest traction.

Then the audio leaked.

No one ever proved who leaked it.

Officer Willis swore it wasn’t him.

Evan said he only sent it to Bumpy.

Lena insisted she didn’t do it—her piece referenced it, but didn’t embed it.

Some anonymous account on social media posted a 34-second clip: Langford’s voice, ugly and clear, dropping the N‑word in full, twice, with venom.

It spread like mold.

Day 3

Langford released a statement his PR firm wrote:

I deeply regret the hurtful language I used in a private conversation that has now become public. Those words do not reflect my values…

It was exactly the kind of non-apology people had learned to tear apart.

Within hours, there were side-by-side memes: his statement, and the transcript of his actual words. The caption under the transcript read: “Apparently his values were on a coffee break.”

Day 4

The city announced that Langford Holdings’ Fair Workplace Certification was “under immediate review” and that their tax benefits were “suspended pending the outcome.”

Investors saw the headline.

Some called their brokers.

Some called Langford.

Most just quietly started moving their money.

Day 6

Tenants in one of his other buildings organized a small protest in the lobby: nothing dramatic, just signs that said “Respect Your Workers” and “No Racism in Our Homes.” Someone live-streamed it. It got more views than the mayor’s last speech.

Day 8

A former employee of one of his sports bars came forward with her own story about racist comments he’d made years earlier.

Then another.

Patterns formed.

The PR firm quietly moved him from their “Featured Clients” page to “Past Clients.”

When Bumpy saw that, he knew.

Langford was radioactive.

In less than two weeks, he’d gone from “unassailable landlord” to “liability with a LinkedIn.”

But that wasn’t the part that made the town stop and stare.

That came on a Wednesday afternoon, three weeks after the lobby incident.

10. The Fall

Harbor Heights had an outdoor plaza downtown: brick, fountains, a little amphitheater where high school bands played once a month. It was nice in that “designed by committee” way, with just enough benches to make the city look thoughtful.

Lorraine and Bumpy were walking through it, carrying groceries, when they saw him.

At first, Bumpy didn’t recognize Victor Langford.

The man sitting on the edge of the fountain didn’t look like the polished bully from the lobby. His hair was uncombed, his shirt wrinkled, his shoes scuffed. The expensive watch was still there, but it looked wrong on him now, like borrowed jewelry.

He was holding a paper coffee cup.

Not drinking from it.

Holding it out.

A cardboard sign leaned against his knees, written in a shaky hand:

“NEED HELP. LOST EVERYTHING.”

Bumpy stopped.

So did Lorraine.

“That can’t be…” Bumpy began.

“It is,” Lorraine said quietly.

Langford looked up.

For a moment, his eyes passed over them without recognition. Then something clicked.

His face drained of the little color it had.

“You,” he said hoarsely. “It’s you.”

Bumpy almost laughed.

“You remember us,” he said.

“Of course I remember you,” Langford snapped, some of his old edge flickering back. “You… you ruined me.”

A few people glanced over.

Lorraine shifted the grocery bag on her hip.

“You ruined yourself,” she said. “We just turned the lights on.”

He clenched the cup so hard it warped.

“Do you have any idea what I’ve lost?” he said. “Investors pulling out, tenants terminating leases, the city bleeding me with penalties… My wife—”

He stopped.

Bumpy raised an eyebrow.

“She left?” he asked.

“She’s at her sister’s,” he muttered. “For now. Says she ‘needs space.’ She liked the guest house. The cars. The dinners. You know what a man is without those things?”

“Still a man,” Lorraine said. “Just without hiding places.”

“Without leverage,” Bumpy said. “Without a cushion of money to bounce off when you fall. You’re experiencing what the rest of us call ‘Tuesday.’”

Langford’s nostrils flared.

“You enjoying this?” he asked. “Seeing me like this? Begging? You people are always so eager to drag someone down when they succeed.”

This time, when he said “you people,” it sounded hollow. Like an old weapon with no bullets left.

“No,” Lorraine said. “You dragged yourself down. You tied your rope to the ugliest part of you and started pulling. We just… let you keep going.”

He laughed then, a broken, brittle sound.

“You think this is forever?” he asked. “I have friends. Connections. I’ll bounce back.”

Bumpy tilted his head.

“Maybe,” he said. “Rich men usually do. The system likes you. But you’re going to bounce back with a Google page that has your voice saying the N‑word on it. You’ll be the guy landlords whisper about when they think about who not to hire for their new project.”

A gust of wind rattled the trees around the plaza.

Langford shivered.

“I’m not asking you for forgiveness,” he said suddenly, unexpected sincerity cracking through. “I know I don’t deserve it. I’m asking you for… help. Any help. I haven’t eaten since yesterday. The cards are frozen. The accounts… everything’s frozen.”

Bumpy looked at his mother.

She looked back.

They didn’t need words.

Lorraine opened her purse and took out a five-dollar bill.

She held it out to Langford.

His eyes flashed—embarrassment, pride, hunger, all tangled.

“You… you think I want charity from you?” he said.

“I think you need to eat,” she said. “And I know what it feels like to be hungry.”

He stared at the bill.

“I called you—” he began.

“I know what you called me,” she said. “That’s why this is a gift, not a favor. You can’t pay it back to me. You can only pay it forward. Or waste it. That’s on you.”

Slowly, as if his hand weighed a thousand pounds, he reached out and took the money.

His fingers brushed hers.

For the first time since she’d met him, he didn’t look down on her.

He just looked at her.

Like another human being.

“Why?” he whispered.

“Because my mother raised me right,” she said. “Yours raised you rich. There’s a difference.”

Bumpy crouched so they were eye-level.

“You’re right about one thing,” he said. “We did ruin the version of you that could call my mom that word and still walk into every room like you owned it. That version needed ruining.”

He nodded at the sign.

“This version?” he said. “He has a shot. If he wants it.”

Langford looked down at the coffee cup.

A few coins rattled at the bottom.

He laughed again, but there was less bitterness in it now.

“Eight hours,” he said.

“What?” Bumpy asked.

“That’s how long it took,” Langford said. “From the moment I stepped off that elevator and opened my mouth… to the moment my lawyer called me on the golf course and said, ‘We have a problem.’ Eight hours. I didn’t even know you’d moved a piece.”

Bumpy stood.

“Funny,” he said. “I thought it took you a lifetime.”

They turned to go.

Behind them, Victor Langford called out.

“Ms. Ellison,” he said.

Lorraine paused.

“Yes?” she asked.

“I’m…” He swallowed. The word seemed to hurt. “…sorry.”

She gave him a small, tired smile.

“You’re hungry,” she said. “Work on being sorry after you eat.”

11. After

The town moved on, because towns always do.

New scandals, new headlines, new faces.

But some things stuck.

Langford Holdings lost its fancy tax breaks. New owners quietly took over some of his properties. His name disappeared from the Chamber of Commerce “Leadership Circle.”

He didn’t end up on the street forever.

It’s hard for men like him to fall all the way through the safety nets money and connections weave.

A cousin in another city gave him a job—low-profile, no public-facing responsibilities, no staff to abuse. It was humbling. Which was the point.

He never regained the shine he’d had in Harbor Heights.

You couldn’t type his name into a search bar without the audio coming up.

Once, years later, he walked past the old Langford building—now rebranded under some bland corporate name—and saw Lorraine’s replacement mopping the floor.

He didn’t say a word.

He nodded to the receptionist, a young Black woman with braids and sharp eyes, and kept moving.

Bumpy, on the other hand, moved up.

He finished his accounting degree, then took a job in compliance, then in risk assessment. Somewhere between spreadsheets and policy manuals, he realized that his talent for spotting patterns—and the patience to follow paper trails—could be a weapon.

He started a small consultancy helping small businesses—especially those owned by people of color—navigate the same systems that had once protected men like Langford. He made sure they got the tax breaks they were actually entitled to, the grants they never heard about, the protections they’d been denied.

“You weaponized the fine print,” Lorraine said one day, proud.

“Someone had to,” he said.

Sometimes, when he told the story—when someone asked how he’d gotten into this line of work—he’d start with the lobby and the slur and the coffee cup by the fountain.

People would gasp at the “begging on the streets” part, the contrast.

They’d ask: “Didn’t that feel… like justice?”

He’d think about his mother handing a five-dollar bill to a man who’d tried to strip her of her dignity.

He’d think about the look on Langford’s face, that moment when power and hunger collided.

And he’d say:

“No. Justice is bigger than one man losing his building. That was just a… correction. A reminder that if you build your life on other people’s backs, the fall is going to hurt when they finally step aside.”

He’d pause.

“And sometimes,” he’d add, “the fall happens a lot faster than you think. About eight hours, give or take.”