What Hitler Generals Said When American Carriers Won at Midway

On June 4, 1942, the world was at war, and the stage was set for a pivotal moment that would alter the course of history. In Berlin, Adolf Hitler was deeply engrossed in military briefings, absorbing updates from the Eastern Front while a distant battle in the Pacific was about to unfold. Little did he know that the events at Midway would not only impact the Pacific theater but also send shockwaves through the highest echelons of Nazi command.

A Routine Briefing in Berlin

As the sun rose over Berlin, Hitler received his routine military briefings in the operations wing of the Reich Chancellery. The atmosphere was tense yet familiar, filled with the smell of cigarette smoke and the sound of rustling papers. The Eastern Front dominated the agenda, but a short intelligence summary from the Pacific was included—a report relayed through German naval attaches and intercepted signals.

The report concerned a Japanese operation near the remote atoll of Midway, northwest of Hawaii. At that moment, the Imperial Japanese Navy was engaged with American carrier forces, but the information was incomplete and cautiously worded. It did not declare victory or defeat, merely reporting contact losses and uncertainty.

For months, German leadership had accepted Japanese naval dominance as a given. The attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 had reinforced this belief, leading to the assumption that Japan controlled the Pacific initiative. This conviction shaped Germany’s strategic calculations, particularly the notion that the United States would remain overstretched, divided between oceans, and slow to concentrate its full strength against Europe.

Initial Reactions: A Peripheral Concern

Inside the German high command, the first reports from Midway were read without alarm. The language was technical, filtered through Japanese channels that emphasized engagement rather than outcome. Aircraft losses were mentioned without totals, and carrier movements were described without confirmation of damage. The battle was framed as ongoing.

Wilhelm Keitel, chief of the armed forces high command, received the same intelligence summary shortly after Hitler. He had spent much of the morning reviewing logistical updates from the Eastern Front, where preparations were underway for a renewed summer offensive. To him, Midway registered as peripheral. Germany’s war would be decided on land in the east; the Pacific War was Japan’s responsibility.

However, as midday approached, additional intercepts and diplomatic cables arrived, complicating the situation. One report referenced significant losses of Japanese aircraft, while another suggested that American carriers were not caught at anchor as they had been at Pearl Harbor, but were already at sea and actively counterattacking. This detail mattered. It implied preparation, intelligence success, and operational competence on the American side—an unwelcome signal for German planners accustomed to underestimating American military effectiveness.

Growing Concern: The Shift in Tone

Alfred Jodl, head of operations, reviewed the evolving intelligence with increasing attention. He had long argued that the United States should not be dismissed as militarily naive. Jodl understood war as a system, not a single battle, and he was sensitive to shifts in momentum. The absence of clear Japanese success concerned him more than confirmed losses would have. In modern warfare, silence often signals damage control.

As the afternoon progressed, internal briefings adjusted their language. The battle was now described as costly, and American resistance was characterized as unexpectedly strong. Japanese objectives were described as contested rather than achieved. Still, no explicit admission of defeat appeared—this restraint reflected both uncertainty and cultural practices. Japanese military communications were designed to preserve authority and confidence, especially with allies.

Within Hitler’s circle, discussions remained limited. Hitler himself showed little outward reaction, focusing instead on immediate priorities and dismissing unfavorable news until it became unavoidable. Yet, the strategic implications were clear enough to register. If American carriers were still operational, the United States retained its offensive capacity. If Japan had failed to destroy them, the American industrial base would have time to act.

The Evening Report: A Decisive Defeat

By early evening, a more detailed assessment reached Berlin through naval intelligence channels. It suggested that at least one Japanese carrier had been severely damaged, possibly lost. The report was marked unconfirmed, but the implication was serious. German naval planners had studied carrier warfare closely, particularly its implications for sea control and power projection. The loss of a carrier was not merely a tactical setback; it was a strategic event.

Carl Dönitz, commander of Germany’s submarine arm, reviewed the information later that night. He had long regarded American shipbuilding capacity as the central problem Germany would eventually face. Submarine warfare depended on attrition and time. If the United States retained its naval corps and accelerated production, then time favored the enemy.

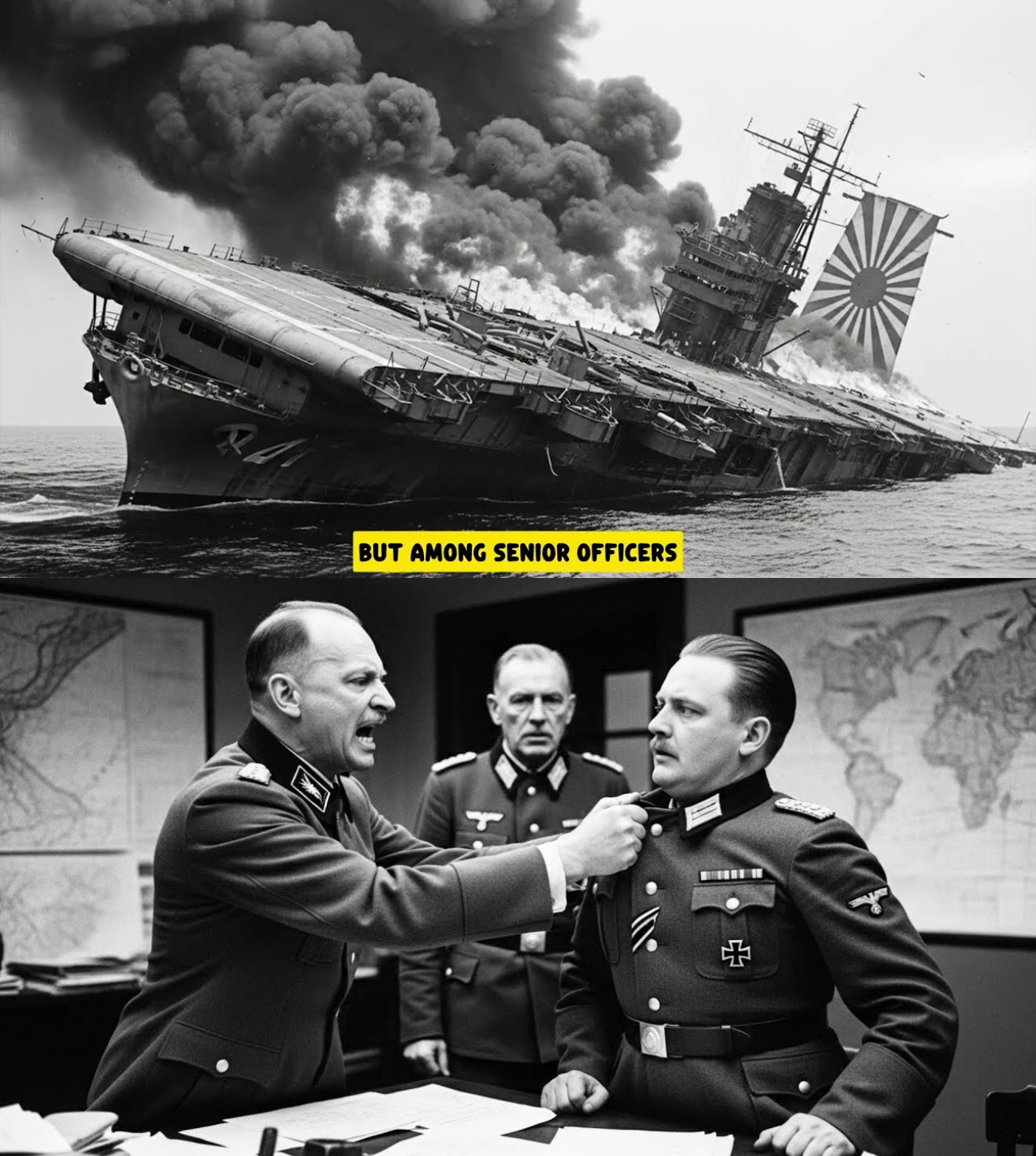

By the end of June 4th, no formal conclusions were issued in Berlin. No statements were made, and no adjustments were announced. However, among senior officers, a quiet reassessment began. The war they envisioned—one in which Japan held the Pacific and Germany defeated the Soviet Union before American power fully mobilized—now contained serious uncertainty. The assumption of uninterrupted Japanese success could no longer be taken for granted.

The Shift in Perspective: A New Reality

Two days after the initial reports from the Pacific, a consolidated intelligence assessment was delivered to the highest levels of German command. The uncertainty that characterized the first day had been replaced by confirmation: four Japanese fleet carriers—Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, and Hiryu—had been destroyed near Midway. Hundreds of experienced pilots and deck crews were gone, while the American carriers involved remained operational. The engagement was no longer described as contested; it was identified as a decisive Japanese defeat.

Hitler received the report during a scheduled military conference, and the setting was familiar. Senior commanders were seated around a long table, maps of the Eastern Front dominating the room. The Pacific update was delivered as a secondary item, but its content immediately disrupted the meeting’s rhythm. Hitler listened intently, his reaction restrained but his posture changing. He began to ask questions—not about Japan’s losses, but about American capabilities. How many carriers were involved? How quickly could replacements be built? Did this result indicate coincidence or competence?

For Hitler, the significance of Midway lay not in the Pacific theater itself but in what it revealed about the United States. His worldview had long rested on the assumption that America was industrially powerful but strategically slow, politically divided, and culturally unprepared for sustained war. Pearl Harbor had been interpreted as confirmation of this belief. Midway challenged that notion.

A Turning Point: The Implications of Midway

Wilhelm Keitel observed the shift in tone immediately. The conversation turned away from Japan’s operational errors and toward American potential. This was an uncomfortable direction for many in the room. German planning had depended on time—time to defeat the Soviet Union, time to force Britain into exhaustion, and time to limit American involvement to material support.

Alfred Jodl addressed the implications directly, noting that Japan had lost not only ships but irreplaceable personnel. Carrier warfare depended on trained air crews and experienced deck officers, losses that could not be quickly replaced. The United States, by contrast, had not lost equivalent assets; its industrial system was already expanding. Shipyards were operating at an unprecedented pace, and training pipelines were producing skilled personnel.

Hitler reacted defensively, criticizing Japanese operational planning and suggesting that the loss reflected tactical misjudgment rather than systemic weakness. He argued that the war in Europe remained decisive and that Japan’s role was to tie down American forces, not to win the war alone. Yet, even as he spoke, the strategic balance he described was under strain.

Carl Dönitz listened carefully, understanding that submarine warfare against American shipping depended on assumptions about escort availability, ship replacement rates, and naval priorities. If the United States retained its carriers and accelerated production, convoy protection would improve, making losses that once seemed sustainable unacceptable.

The Psychological Impact: A Quiet Reassessment

As the conference ended, no orders were issued in response to Midway. There was no operational adjustment Germany could make in the Pacific, but the illusion of predictability had been broken. The war was no longer unfolding according to the sequence Germany anticipated. The enemy Hitler had dismissed as decadent and indecisive had demonstrated clarity and resolve.

That evening, internal memoranda circulated among senior planners. They did not use dramatic language; they did not predict defeat. However, they revised timelines, extended estimates, and acknowledged risk. These documents would never be read aloud to the public; they were meant for those who understood what had changed.

Midway had not altered the battlefield in Europe. The Soviet armies still stood in the east, and British bombers continued to strike German cities. But the horizon had shifted. The United States had revealed itself as an active, capable belligerent. The war Germany intended to conclude quickly was becoming a war of endurance.

The Long Shadow of Midway

In the days and weeks following the Battle of Midway, the language used inside Germany’s senior command changed in tone and content. Publicly, nothing was said. Official communications continued to emphasize confidence, resolve, and inevitable victory. Privately, however, the senior leadership of the German military began to speak with a clarity that had been absent since the early years of the war.

Midway became a fixed reference point in internal discussions, not because of its location or its participants, but because of what it revealed about the enemy Germany now faced. Alfred Jodl recorded his concerns in operational memoranda circulated only among the highest planning staff. He focused not on Japan’s mistakes but on the American response, noting that American carrier forces were not only present but properly positioned, indicating successful intelligence work and command discipline.

As the war continued, the generals who had once underestimated the United States now found themselves grappling with the reality of a formidable opponent. The Battle of Midway had not only marked a turning point in the Pacific but had also reshaped the German military’s understanding of the conflict. The United States was no longer viewed as a passive participant; it was an active force, learning, adapting, and preparing for a prolonged struggle.

Conclusion: The End of Illusions

By the end of 1942, the Battle of Midway had disappeared from public German discourse. It was not mentioned in speeches, newspapers, or official summaries of the war. No explanations were offered, and no lessons were acknowledged. The event existed only in internal documents and private understanding.

For the German military leadership, Midway was no longer a shock; it had become a quiet reference point, a moment fixed in memory as the first clear signal that the war’s direction could not be reversed. Adolf Hitler continued to speak of ultimate victory, but his decisions increasingly reflected constraint rather than confidence.

Midway’s lessons were profound, revealing the true nature of the conflict Germany had entered—a war not decided by singular victories but by the accumulation of capacity over time. The question for the German leadership was no longer how to win but how long the system could hold before the imbalance became impossible to conceal.

As the war dragged on, the generals who understood the implications of Midway carried the burden of foresight without agency. They continued to serve a system that could not adapt to the reality it faced, their words preserved in internal records and private reflections, revealing a war already lost long before it was publicly conceded. The enduring lesson of Midway was clear: modern war is decided not by belief or declaration, but by capacity, adaptation, and time.