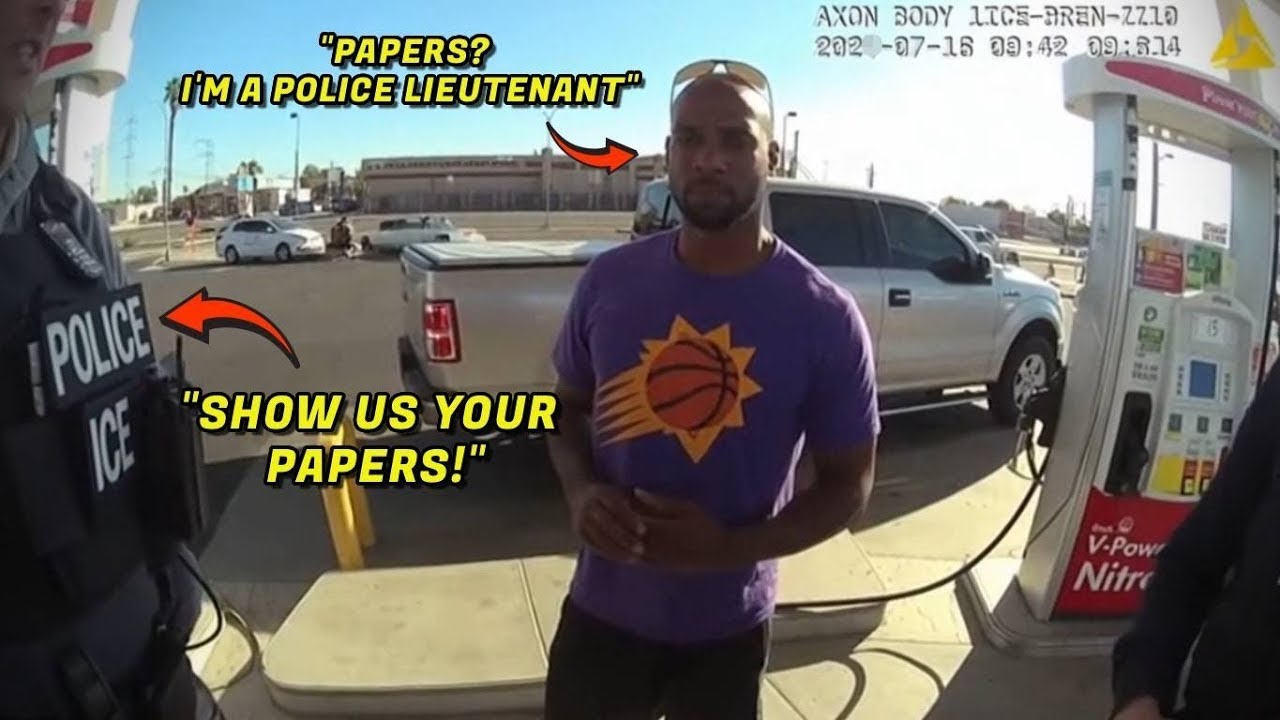

ICE Agent Demands Papers from Off-Duty Black Police Officer — He’s a Lieutenant, Wins $13.9M Lawsuit

.

.

One Stop Away

At 9:47 a.m., the sun was already punishing the asphalt.

The Shell station on McDowell Road shimmered in the heat, the kind that blurred the edges of parked cars and made the air above the pavement ripple like disturbed water. Commuters hurried in and out of the convenience store. A delivery truck idled near the side entrance. The scent of gasoline mixed with burnt coffee drifting through the open door.

Lieutenant Marcus Hayes stood beside pump number six, one hand resting lightly on the nozzle as the final gallons clicked into his Ford F-150.

He had just finished an overnight shift.

Twenty-three years with the Phoenix Police Department had trained his body to operate on little sleep, but exhaustion still sat behind his eyes. He wore basketball shorts, a faded Phoenix Suns T-shirt, and running shoes. His badge and service weapon were locked inside the truck’s center console. Off duty, but never entirely off alert.

He replaced the nozzle and twisted the gas cap tight.

That was when he noticed the white SUV.

It had government plates. The engine was still running.

Three men stepped out.

They moved with spacing that made his instincts sharpen instantly—triangular formation, staggered positions, hands hovering near their waists. Law enforcement.

His mind cataloged details automatically.

Tactical vests. ICE patches.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Agent Todd Brennan approached first, his expression already set in something that wasn’t curiosity.

“Papers,” Brennan said flatly. “Immigration check. Need to see identification and proof of legal status.”

Hayes blinked once.

“Excuse me?”

“We’re conducting enforcement operations in this area. Show documentation.”

The words were delivered like routine instructions. Rehearsed. Unquestioned.

Hayes removed his sunglasses slowly. His hands stayed visible.

“I’m a police lieutenant,” he said calmly. “Phoenix PD. Marcus Hayes. My badge is in my truck.”

Brennan didn’t move.

“Sure you are. Everyone’s got a story.”

The other two agents—Valdez and Kim—shifted slightly, widening the containment angle. Hayes recognized the maneuver immediately.

They had already decided something about him.

“My wallet is in my back pocket,” Hayes said. “You want me to reach for it?”

“Slowly,” Brennan replied. “Two fingers.”

Hayes retrieved his wallet with deliberate care and handed over his Arizona driver’s license.

Brennan glanced at it.

“This doesn’t prove citizenship.”

Hayes stared at him.

“It’s a state-issued ID.”

“I need passport, birth certificate, naturalization papers—something that proves you’re here legally.”

The heat pressed against Hayes’s skin, but a colder sensation crept into his chest.

“I was born in Tucson,” he said evenly. “My father was born in Tucson. I’ve been a police officer in this city for twenty-three years.”

Valdez stepped closer.

“We have authority to verify status.”

“Based on what reasonable suspicion?” Hayes asked.

No one answered directly.

Instead, Brennan said, “Turn around. You’re being detained for verification.”

The woman at pump three raised her phone.

A man near the entrance paused mid-step.

Hayes felt the weight of two decades of policing settle into his spine. He had given commands like this before. He knew how authority felt in his voice.

He also knew what it sounded like when it lacked foundation.

“I am not resisting,” he said clearly. “I am invoking my Fourth Amendment rights. You have no articulable suspicion to detain me.”

Brennan’s jaw tightened.

“Turn around.”

Hayes did not move.

“Call my precinct,” he said. “Central Division. Ask for Captain Williams. Badge number 2847.”

Valdez reached for his arm.

Hayes stepped back, hands raised higher.

“Do not touch me without cause.”

That was the moment the air shifted.

“Subject is resisting,” Brennan said.

They moved in unison.

Hands grabbed his arms. Metal cuffs snapped around his wrists. Not painfully—but tight enough to send a message.

Gas station conversations fell silent.

Hayes kept his voice steady.

“My name is Lieutenant Marcus Hayes. Phoenix Police Department. I am a United States citizen. This detention is unlawful.”

They walked him to the SUV.

He caught sight of his truck in the reflection of the tinted window—keys still in the ignition, badge locked inside.

The back seat smelled of vinyl and something older—fear, maybe.

As the SUV pulled away, Hayes closed his eyes briefly.

He had spent a career navigating volatile situations. He had defused domestic disputes, confronted armed suspects, mediated protests.

Now he sat in handcuffs because three federal agents had looked at him and seen something that didn’t belong.

At the ICE field office, he was placed in a holding room.

Concrete walls. Metal bench. No clock.

The door shut with bureaucratic finality.

An hour passed.

Then another.

No one explained anything.

Hayes ran through possibilities in his head. They would verify eventually. They would realize the mistake.

The question was how long it would take—and what it meant that it had happened at all.

At 12:43 p.m., the door opened.

A supervisor entered.

“Lieutenant Hayes,” the man said carefully. “We’ve verified your identity. You’re free to go.”

Hayes stood slowly.

“You verified it how?” he asked.

“We contacted Phoenix PD.”

“So you could have done that at the gas station.”

Silence.

The supervisor cleared his throat.

“There was a procedural delay.”

Hayes let out a short breath.

“You detained a police lieutenant for three hours because I was brown at a gas station,” he said quietly. “Call it what it is.”

The supervisor didn’t respond.

They drove him back.

His truck was still there.

He checked the console—badge intact, weapon secured.

He drove straight to headquarters.

Captain Williams looked up as Hayes entered the office.

“Marcus? What’s wrong?”

Hayes told him.

Every detail.

The stop. The cuffs. The holding room.

Williams’s expression hardened with each sentence.

“They detained you for what?” he asked finally.

“For existing in the wrong skin,” Hayes replied.

Within a week, Hayes had retained counsel.

Amanda Torres was known for federal civil rights litigation. She listened without interrupting as Hayes recounted the event again.

“Do you want an apology,” she asked, “or accountability?”

“Accountability,” he said.

Torres filed suit.

The complaint detailed unlawful detention, racial profiling, violation of constitutional rights under color of federal authority.

The body camera footage was obtained.

Three synchronized angles.

Three federal agents approaching a man pumping gas.

Hayes identifying himself repeatedly.

The refusal to verify.

The handcuffs.

The transport.

The holding cell.

The footage was unembellished.

It didn’t need to be.

The government offered $75,000 to settle.

Torres declined.

They offered $300,000.

“No,” she said again.

The case went to trial nineteen months later.

The courtroom was full.

Officers in uniform sat behind Hayes in quiet solidarity. Community members filled the remaining seats. Reporters typed rapidly at laptops balanced on their knees.

The footage was played on a large screen.

Jurors leaned forward.

They watched Hayes calmly state his name and badge number.

They watched the agents dismiss it.

They watched him cite constitutional protections.

They watched him be handcuffed anyway.

During cross-examination, Torres asked Brennan, “What specific fact suggested Lieutenant Hayes was violating immigration law?”

Brennan shifted in his seat.

“We were operating based on intelligence about the area.”

“The area,” Torres repeated. “So not this individual.”

“We make assessments.”

“Based on what?”

Silence.

“Was it his behavior?”

“No.”

“His vehicle?”

“No.”

“His clothing?”

“No.”

“What was it then?”

The courtroom felt smaller in that moment.

Brennan did not answer directly.

The jury didn’t need him to.

Hayes testified for hours.

He spoke about his career. About teaching younger officers to respect constitutional boundaries. About the humiliation of sitting in a federal holding cell knowing he had spent decades upholding the law.

“I know what reasonable suspicion looks like,” he told the jury. “They didn’t have it.”

The defense argued procedure.

Torres argued principle.

After eight days of deliberation, the jury returned.

Liable on all counts.

Damages would be determined next.

Expert witnesses described the psychological toll of wrongful detention—especially on someone who had sworn to uphold the system that failed him.

When the final number was read, the courtroom fell silent.

$13.9 million.

$9.4 million in compensatory damages.

$4.5 million in punitive damages.

Hayes did not smile.

He nodded once.

Outside, cameras flashed.

Reporters shouted questions.

“Lieutenant Hayes, do you feel vindicated?”

He paused before answering.

“I feel heard,” he said. “There’s a difference.”

The Department of Homeland Security issued a statement about policy reviews.

The agents involved were reassigned pending internal investigation.

Training materials were updated. Language was clarified.

Hayes continued serving for three more years before retiring.

He used part of the settlement to establish a legal defense fund for individuals detained without proper cause.

“Not everyone has the resources to fight back,” he said at the fund’s launch. “But everyone deserves their rights.”

The Shell station on McDowell still operates.

Pump number six still clicks at the same steady rhythm.

Most mornings, people fill their tanks without incident.

But sometimes, a younger officer in Phoenix PD training will hear about the case during constitutional law instruction.

They’ll watch the footage.

They’ll discuss articulable suspicion.

They’ll debate federal authority and civil liberties.

And someone will inevitably ask, “How did this happen?”

The answer isn’t complicated.

It happened because assumptions replaced evidence.

Because authority went unquestioned in the moment.

Because three agents saw a demographic profile instead of a person.

The $13.9 million did not erase the three hours in a holding cell.

It did not undo the public humiliation.

But it did send a message.

Citizenship is not proven at a gas pump.

Rights are not optional.

And badges—local or federal—do not place anyone above constitutional limits.

Years later, Hayes was asked at a community forum what he had learned.

He considered the question carefully.

“That the Constitution isn’t self-executing,” he said. “It only works when people insist on it.”

He paused.

“And that sometimes the only difference between injustice and accountability is whether someone decides to push back.”

On a Tuesday morning in Phoenix, under a punishing desert sun, Marcus Hayes pushed back.

And the cameras did not blink.