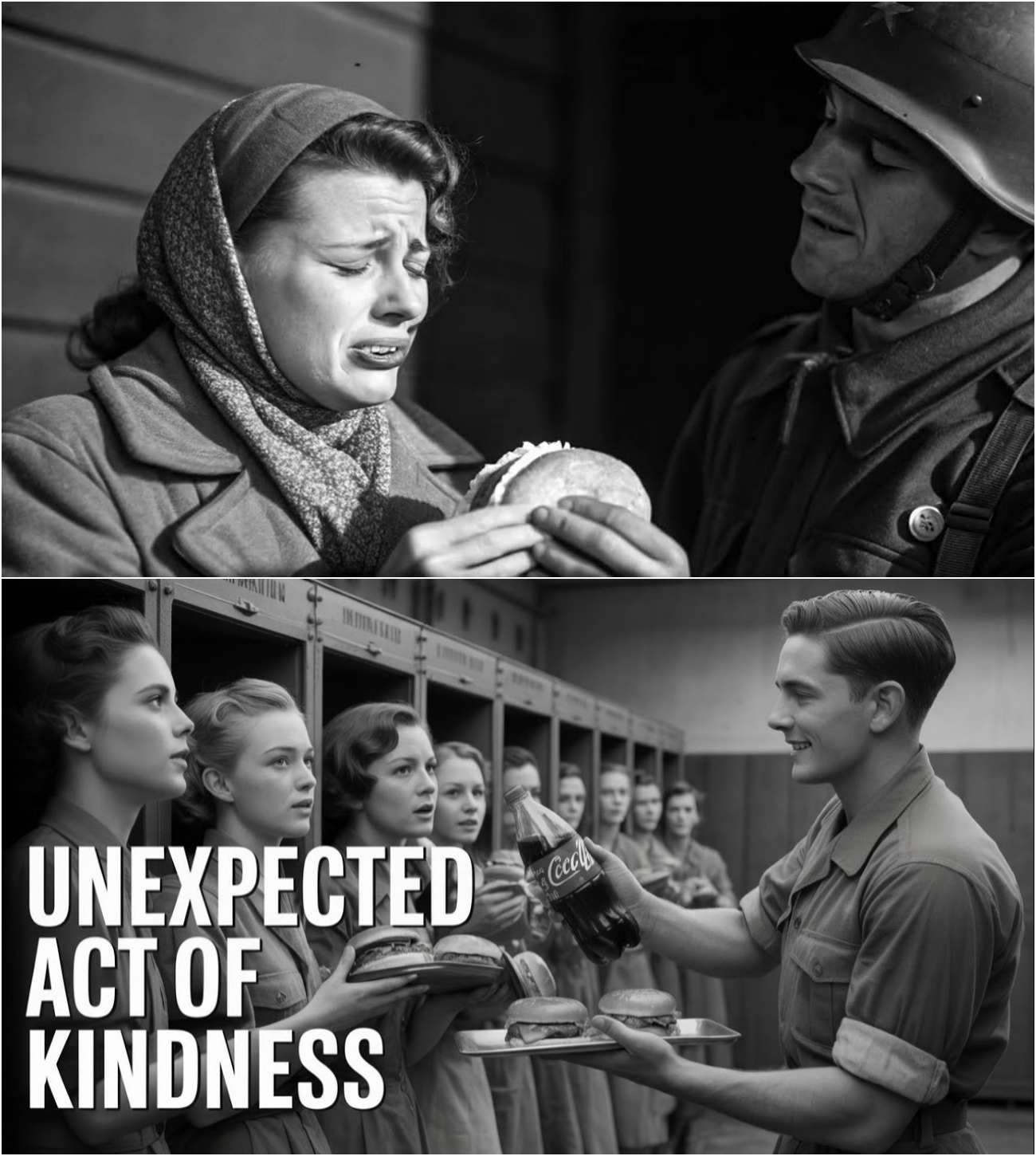

Can We Have Leftovers” German POW Women Asked, Americans Gave Them Coca Cola and Hamburgers

In June 1945, as the war in Europe came to a close, a group of 281 female German prisoners of war stepped off a dusty train at Camp Hearn, Texas. These women, members of the Luftwaffe’s signal corps, had been captured during the invasion of Normandy. Their uniforms were tattered, their shoes barely held together, and many had not eaten real food in days. They expected hostility from their captors, but what awaited them was something entirely unexpected—a warm welcome and a feast that would change their lives.

The Arrival at Camp Hearn

The summer of 1945 was the hottest on record in Texas, and as the women arrived at Camp Hearn, they were met not with the scorn they anticipated but with the sounds of a cheerful U.S. Army band playing “Don’t Fence Me In.” The camp commander, Colonel James P. Cooper, stepped forward with a thick Texas drawl, assuring the women that while they were prisoners, they were also guests.

“Ladies, welcome to Texas,” he said, pointing to long tables set under the mess tent, adorned with white tablecloths and filled with the mouthwatering aroma of freshly baked biscuits and creamy sawmill gravy. For the women, who had endured the horrors of war and the deprivation of captivity, this was a surreal moment.

The First Bite of Freedom

Among the women was 18-year-old Hannalor Miller from Hamburg. She hadn’t tasted butter since 1942, and as she stepped up to the table, her heart raced. A smiling mess sergeant named Leroy Jackson piled her plate high with biscuits, gravy, scrambled eggs, and crispy bacon, insisting, “You look like you need love and sugar.”

When Hannalor took her first bite of the biscuit soaked in gravy, she broke down in tears. The overwhelming flavors and the kindness of the American soldiers were too much to bear. Around her, other women were similarly moved, stuffing biscuits into their pockets, hugging the mess sergeants, and crying tears of joy and relief.

Leroy Jackson, wiping his own eyes with his apron, declared, “My mama taught me never to let a woman go hungry. Don’t matter what flag she wore.” That night, for the first time in years, the women slept in real beds with clean sheets, each bunk adorned with care packages containing toothbrushes, soap, and two biscuits wrapped in wax paper.

A New Community

As the weeks turned into months, Camp Hearn became a symbol of compassion and humanity. Local church ladies began bringing homemade peach cobbler every Sunday, while farmers’ wives taught the German women how to make biscuits properly. Children left candy bars on the fence with notes of gratitude for their help during the cotton harvest.

The German women worked voluntarily in the fields, earning 80 cents a day in camp script, which they used to buy lipstick and perfume. They sent postcards home, declaring simply, “We are treated like human beings again.”

By Christmas 1945, the mess hall was decorated with paper chains and a ten-foot cedar tree. The women, now dressed in neat denim dresses made from army surplus, sang carols alongside their American guards, both sides shedding tears into their eggnog.

The Day of Repatriation

On May 8, 1946, the first group of women was set to be repatriated. At the train station in Hearn, Texas, each woman carried a small paper bag filled with two biscuits and gravy in a tin, still warm. Hannalor, now 19, approached Leroy Jackson, who had come to say goodbye. She handed him a tiny embroidered handkerchief with the words “Danka, Texas,” stitched in red.

Then, in a gesture that surprised everyone, she hugged him tightly, gravy tin and all. It was a moment of connection that transcended the boundaries of nationality and war.

A Reunion After Fifty Years

Fast forward to May 8, 1996. The Hearn Train Station was once again filled with emotion as 42 of the original women returned, now grandmothers wearing the same denim dresses they had kept all those years. Leroy Jackson, now 74 and retired, stood on the platform with his daughter and twelve grandchildren, ready to welcome them back.

The women opened a large picnic basket filled with hundreds of perfect Texas biscuits swimming in sawmill gravy, made exactly as they remembered from 1945. Hannalor, now 69, walked up to Leroy and placed one biscuit in his hand, saying, “You gave us biscuits with gravy first, and with them, you gave us back our hearts.”

They gathered together under the Texas sun, sharing food, laughter, and memories. It was a poignant reminder of how a simple act of kindness could forge bonds that lasted a lifetime.

The Power of Food and Compassion

The story of the women of Camp Hearn and their American guards highlights the profound impact of compassion and humanity during one of history’s darkest times. In a world torn apart by war, food became a bridge between enemies, transforming prisoners into guests and creating a sense of community against the backdrop of conflict.

Leroy Jackson’s decision to feed the German women was not just an act of kindness; it was a powerful statement that hunger knows no nationality. It showed that even amidst the horrors of war, there is room for empathy, understanding, and connection.

As we reflect on this remarkable story, we are reminded that sometimes the simplest gestures—a warm meal, a smile, a hug—can have the most profound effects. The women of Camp Hearn discovered that peace could taste like sausage gravy and feel like home, a lesson that resonates even today.

In the end, the bonds formed over biscuits and gravy, tears, and laughter served as a testament to the resilience of the human spirit. The war may have left scars, but the kindness shown at Camp Hearn healed wounds in ways that words alone could not express.