The Day a Sniper Did What Patton Dreamed Of: Publicly Humiliating Montgomery

.

.

.

The Day a One‑Eyed Canadian Sniper Humiliated Montgomery—And What the Story Reveals About Power, Pride, and the Price Paid in Mud

Spring, 1945 — The Netherlands.

A parade ground near the German border, where the grass is wet and the air smells of diesel exhaust and cold earth. Canadian soldiers stand in rigid ranks, boots mirror-bright, brass catching thin sunlight. A staff car rolls to a stop. Out steps Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery—“Monty” to the press, commander of the 21st Army Group, public face of British victory, master of the carefully staged moment.

The ceremony is meant to be simple: a medal presentation, a photograph, a headline. The kind of crisp ritual that turns the chaos of war into a neat narrative.

Then a private soldier in an eyepatch walks forward.

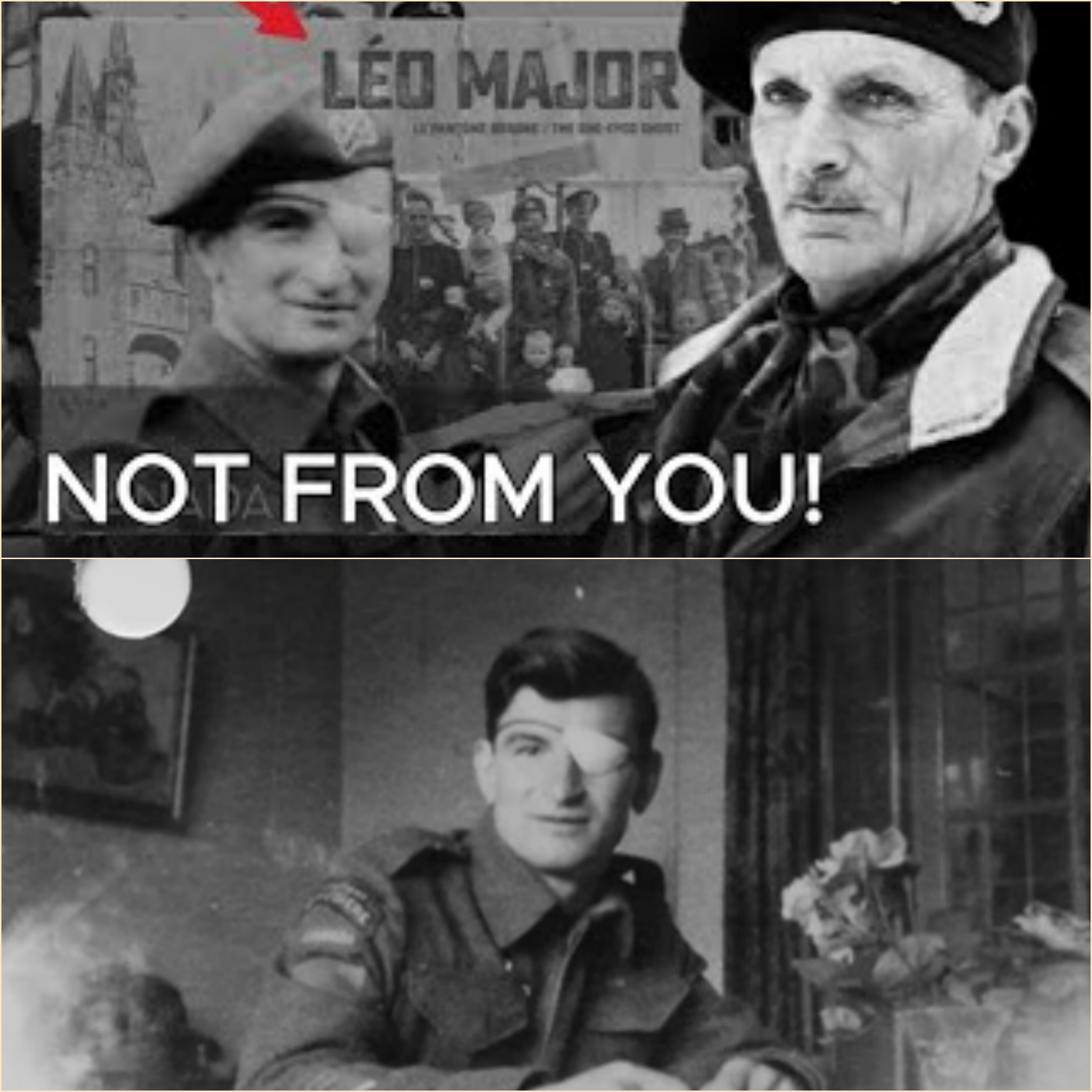

His name is Léo Major, a French‑Canadian scout and sniper whose wartime reputation—part fact, part legend—has already begun to outgrow the army’s ability to manage it. The story that follows has been told for decades in barracks, memoirs, and regimental lore: Montgomery extends the medal. Major refuses it. Major calls him incompetent. Major turns his back on the British Empire and walks away.

It is the kind of scene General George S. Patton—the Allied commander who openly despised Montgomery—might have dreamed about: someone, finally, humiliating Monty in public. Not with memos or sarcastic briefings, but with the one weapon that can pierce a commander’s armor faster than artillery—contempt delivered in front of witnesses.

But did it happen exactly that way? What do we actually know? And why does this story still burn so hot, eighty years later?

This is an account of the incident as it’s widely recounted, the historical context that made it plausible, and the deeper reason it refuses to die: because it captures a truth soldiers recognize instantly—the distance between those who bleed and those who brief.

A Ceremony Built for Myth

Military awards ceremonies are not just about courage. They are about control—a way to take violence and compress it into a symbol that can be pinned, photographed, and filed.

By spring 1945, Montgomery’s public image was already a project with momentum. He wore his black beret like a trademark. He walked with the confidence of a man who believed history owed him flattering captions. He was widely admired as a careful commander who avoided unnecessary slaughter—especially in Britain—yet criticized by others as overly cautious, self‑promoting, and politically sharp-elbowed.

The Canadians lined up that day were not British regulars. They were men from a force that had taken a particular share of the war’s unglamorous work: waterlogged fighting in lowlands, savage clearing operations, and attritional battles that rarely produced dramatic photographs.

And they were waiting for Montgomery, a man who—depending on the account—often treated the Canadian First Army as a useful tool, not a partner.

Into that ceremony walked Léo Major, and even before he spoke, he looked out of place.

He wore an eyepatch.

Not the theatrical kind. The practical kind.

The kind that tells you a man has already paid for this war with a piece of his body and has decided, stubbornly, that payment wasn’t enough to excuse him from returning to the front.

Who Was Léo Major?

Léo Major wasn’t famous because he was charming. He was famous because the battlefield kept producing stories about him that sounded impossible, and then officers kept confirming enough of them to make the rumors harder to dismiss.

He was a French‑Canadian from Quebec, known for bluntness, aggression, and an instinct for operating alone. He served as a scout—an occupation where you win not by force but by nerve, speed, and the willingness to move through darkness while everyone else stays still.

In 1944, he lost his left eye to a phosphorus grenade. For most soldiers, that injury ends a frontline career. Major reportedly refused to go home, telling doctors he only needed one eye to shoot.

Whether the exact wording is literal or polished by retelling, the point stands: he came back.

That matters, because the story of his confrontation with Montgomery only makes sense if you understand the kind of man who could do it. It wasn’t a naïve private unaware of consequences. It was a soldier with a reputation strong enough to become a shield.

Montgomery, Patton, and the War for Narrative

Montgomery wasn’t merely a battlefield commander; he was also a commander in the war for credit.

That is not unusual. High command is politics with maps.

But Monty had a particular talent for shaping perception: briefing style, press access, carefully constructed stories of methodical British excellence. Americans admired the discipline and disliked the tone. Many British adored him. Many other Allied commanders found him maddening.

Patton, in particular, bristled. Patton’s philosophy was speed, shock, and relentless pressure—he believed hesitation cost lives. Montgomery’s philosophy emphasized careful buildup, overwhelming force, and set‑piece battles. Patton saw that as caution bordering on vanity; Montgomery saw Patton as recklessness bordering on disaster.

So when people say “Patton dreamed of humiliating Montgomery,” they aren’t imagining a cartoon rivalry. They’re describing a real clash of war philosophies—and egos—playing out at the top of the Allied pyramid.

A story where a low‑ranking soldier publicly insults Montgomery, then walks away unpunished, is irresistible in that context. It’s a fantasy of the powerless puncturing the powerful. It’s also a warning: a commander’s reputation can’t always hold back the anger of the men paying the bill.

The Ghost in the Mud: The Scheldt and the Price of Delay

To understand why any Canadian soldier might harbor fury at Montgomery, you have to step back into late 1944—into a campaign that, for Canadians, became synonymous with bitter sacrifice: the Battle of the Scheldt.

In September 1944, the Allies captured Antwerp—one of Europe’s great ports. But capturing a port is not the same as using it. Antwerp’s access to the sea runs through the Scheldt estuary, and the Germans still held the banks and islands controlling that route.

Until the Scheldt was cleared, Antwerp could not fully function as the logistical artery the Allied advance desperately needed. The longer it remained closed, the longer Allied armies relied on stretched supply lines.

The Canadian First Army—under General Harry Crerar—was tasked with clearing the Scheldt. The terrain was low, flooded, mined, defended, and perfect for artillery observation. Men fought in freezing mud and water, in flatlands where there was nowhere to hide and nowhere to rest. Amphibious vehicles, engineers, artillery support, and air support could mean the difference between a hard battle and a massacre.

The grievance, as many Canadian accounts frame it, is that clearing the Scheldt did not receive the priority it deserved—because Montgomery focused energy and resources elsewhere, especially on the ambitious airborne offensive Operation Market Garden.

Market Garden is remembered for its drama and its heartbreak—paratroopers dropping into the Netherlands, bridges seized and lost, the phrase “a bridge too far.” In the shadow of that drama, the Scheldt was a grind that produced few cinematic images and many casualties.

Canadian losses in the Scheldt campaign were severe. Numbers vary by source and definition (killed vs. total casualties), but the general picture is consistent: it was costly, miserable, and felt—at the soldier level—like a price paid for a strategic delay at higher levels.

This is where the legend’s emotional fuel comes from. If you are a scout like Léo Major and you watch men drown in mud, bleed on dikes, and vanish into minefields while commanders argue about priorities, your hatred does not need to be philosophical.

It becomes personal.

The Night That Built the Legend: Capturing Germans Alone

Within the lore surrounding Léo Major, one episode is repeated as proof of his audacity: during the Scheldt fighting, he reportedly captured a large number of German soldiers—dozens—during a reconnaissance mission, using shock, aggression, and the psychological collapse that comes when a defender believes a much larger force is attacking.

Some versions say he marched 93 prisoners back alone.

That figure appears in multiple retellings and is often linked to his recommendation for the Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM). In wartime, extraordinary claims do sometimes have extraordinary documentation—war diaries, citations, officer statements. But retellings can inflate details over time, compressing complex events into a single heroic silhouette.

What is not in doubt is that Major earned a reputation for aggressive scouting and a willingness to operate independently. He was decorated for bravery. He later earned a second award for courage in Korea—making him one of the rare Canadians recognized for gallantry in two wars.

The point is not that every number in every telling is flawless.

The point is that by spring 1945, enough people believed Major was extraordinary that disciplining him publicly would have been a problem.

And that sets the stage for what happens on the parade ground.

The Moment: “I Will Not Let a Man Like You Pin It On Me”

In the most vivid version of the story, the parade ground is quiet enough to hear the wind snap canvas and flags. Montgomery holds the velvet cushion. The medal glints.

Major steps forward—but not with the clean, obedient rhythm of ceremony. He stops short or stands too close, depending on the telling. He does not salute properly. He looks at the medal, then up at Montgomery’s face with one cold eye.

Then he speaks.

Not a shout. A statement.

He calls Montgomery incompetent. He implies Montgomery is responsible for the deaths of Canadians in the Scheldt. He refuses to accept the medal from him—saying, in some versions:

“I will not let a man like you pin a medal on me.”

And then he turns and walks away, leaving Montgomery holding a piece of metal that has suddenly become, in that instant, not an honor but a question.

Did those words occur exactly as quoted? We cannot treat battlefield lore like a court transcript. But the underlying claim—that Major refused a decoration from Montgomery and voiced contempt—has circulated for decades with remarkable persistence, particularly in Canadian military storytelling.

And even if you strip away the sharpest dialogue, the core symbolism remains: a soldier refusing to participate in a commander’s narrative.

Why Wasn’t He Arrested?

Here is where the story becomes more than a personal clash. If a private soldier publicly insults a field marshal, the consequences in a strict army should be immediate.

So why, in the legend, does Montgomery swallow it?

Because Montgomery is not simply a man—he is a commander operating inside a political machine. Arresting a celebrated Canadian hero at the edge of victory could have created a scandal. It could have provoked outrage in Canadian ranks. It could have forced uncomfortable questions about the Scheldt, about priorities, about casualties, about responsibility.

Sometimes, in war, it is safer for high command to accept humiliation than to ignite a fire it cannot control.

And so—again, in the commonly told version—Montgomery does nothing. The ceremony ends awkwardly. The medal goes back into its case. Montgomery returns to his car with his pride intact on paper and wounded in every other way.

Back in barracks, the story detonates like a grenade.

Soldiers cheer. Not because they hate medals, but because someone finally said the forbidden words out loud, on their behalf, to the man whose decisions had felt distant and fatal.

The News Value: Why This Incident Still Matters

At first glance, this is a delicious anecdote: a one‑eyed Canadian sniper humiliates a famous British field marshal, and the field marshal can’t do anything about it.

But the reason it persists—why it gets retold with such relish—is that it dramatizes a truth about war that official histories often soften:

1) Rank can command obedience. It cannot command respect.

Respect is earned where the danger is immediate. The soldier’s test for leadership is simple: does this commander’s style keep us alive, or does it spend us carelessly?

2) Strategy has a body count—even when it’s “correct.”

Commanders can argue for decades about whether a priority shift was justified. Soldiers remember the mud, the wounded, and the empty bunks. Strategic logic does not erase grief.

3) The war for glory can be as vicious as the war for ground.

Montgomery understood headlines. Patton did too. So did many others. But soldiers often view that hunger as a kind of betrayal—because a man who seeks credit may be tempted to accept costs he will not personally pay.

Zwolle: The Tactical Rebuttal to “Higher Headquarters”

The legend of Léo Major does not end with a parade ground. It escalates.

In April 1945, Major is associated with one of the most famous Canadian individual exploits of the war: the liberation of Zwolle in the Netherlands.

The broad outline, supported by multiple accounts, is this: Major and a companion were sent to scout German positions ahead of an advance. His companion was killed. Major continued alone. He moved through the city at night, firing and throwing grenades, creating enough confusion that German forces believed a larger attack was underway. By morning, German troops withdrew, and the city was spared a destructive bombardment.

In the storytelling tradition, Zwolle becomes the ultimate rebuke to commanders who solve problems with heavy artillery: a single scout’s audacity and nerve preventing civilian deaths and urban destruction.

Even if you approach the details with caution—as historians should—the symbolic meaning is clear. Major embodies a kind of soldier’s logic:

Speed beats committees.

Initiative saves lives.

Caution at the top can become carnage at the bottom.

Whether that is always true is beside the point; it is what makes the story resonate.

What We Can Say with Confidence—and What We Should Treat Carefully

Because you asked for a news-style longform feature, it’s important to separate:

What is broadly supported

Léo Major was a highly decorated Canadian scout/sniper.

He lost an eye in WWII and returned to service.

He performed actions of notable bravery, including operations linked to Zwolle.

Montgomery was a polarizing Allied commander.

Canadians bore heavy losses in the Scheldt campaign.

There was real Allied controversy over strategic priorities in late 1944.

What is widely repeated but should be treated as “reported” or “legendary” unless primary documentation is produced

The exact parade-ground dialogue (“incompetent,” “I will not let a man like you…”)

The precise staging of a public refusal witnessed by staff officers in the described manner

The exact prisoner count in specific single‑handed actions as popularly narrated

This doesn’t “debunk” the story. It places it in its proper category: a wartime incident remembered through soldier culture, retold because it expresses emotional truth even when the transcript is fuzzy.

That’s often how military legends work. They condense a thousand resentments into one clean scene.

The Final Image: A Field Marshal Holding an Unwanted Medal

Even if you strip the story to its core, it remains powerful:

A medal, meant to symbolize courage, becomes a mirror held up to command.

A field marshal, used to directing armies, is forced to stand still and absorb the judgment of a private soldier.

And a one‑eyed Canadian walks away—not from honor, but from a narrative he refuses to validate.

In an age when wars are still narrated with maps and press conferences, the legend of Léo Major endures as a reminder that the true audit of leadership is not conducted in headquarters.

It is conducted in flooded fields, in mine‑laced dikes, in ruined streets at night—by the people who have to carry out the orders.