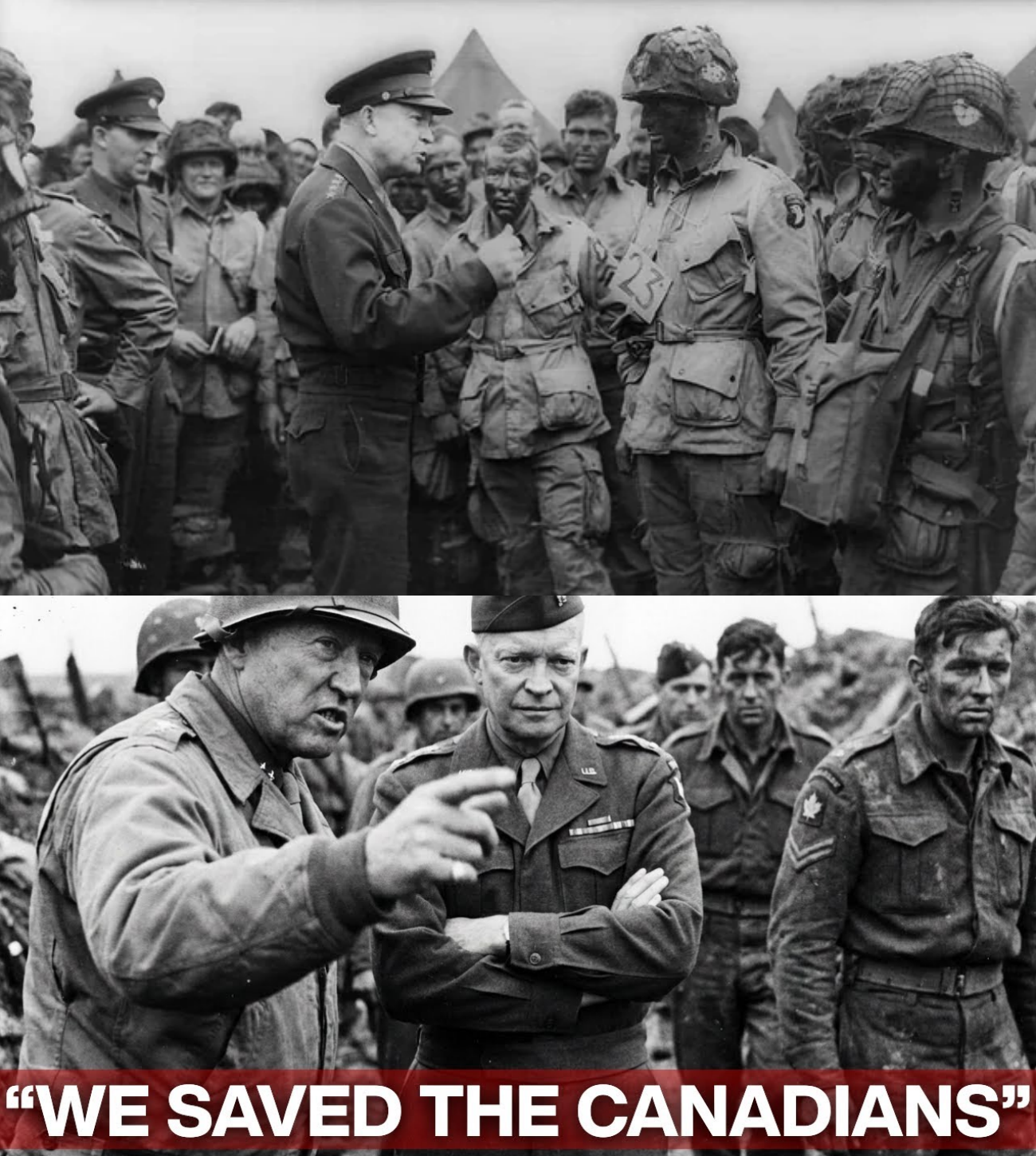

What Eisenhower Said When Patton Claimed Credit for the CANADIAN VICTORY

In August 1944, as the Allied forces pushed deeper into France, a critical moment unfolded that would shape the narrative of World War II. At the heart of this story was a struggle not just for military victory but for historical recognition. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force, found himself facing a dilemma that would test his leadership and integrity. The conflict centered around General George S. Patton Jr., a commanding figure known for his bravado and ambition, who sought to claim credit for a victory that was not entirely his own.

The Context of War

The backdrop of this confrontation was the aftermath of D-Day, when Allied troops stormed the beaches of Normandy on June 6, 1944. Over the following weeks, they fought fiercely to break through German defenses, suffering heavy casualties in the process. By mid-August, the Allies had successfully trapped a significant number of German soldiers in a pocket near the towns of Falaise and Argentan—an encirclement that would become known as the “Filets pocket.”

As the Allies tightened their grip, two armies were poised to seal the fate of the trapped German forces: Patton’s Third Army advancing from the south and the First Canadian Army, along with Polish troops, pushing from the north. The question was simple yet profound: which army would close the gap first? The answer would not only determine the outcome of the battle but also shape the historical narrative of the war.

The Canadian Push

On August 14, 1944, the Canadians launched Operation Tractable, a brutal assault against the entrenched German forces. They faced some of the toughest divisions the Germans had left, including the fanatical SS units. The Canadians were determined to advance despite the odds. Over the next few days, they fought relentlessly, suffering over 5,000 casualties while pushing through fields and villages littered with the debris of war.

The operation was marked by chaos and tragedy. Friendly fire incidents occurred due to the smoke and confusion of battle, resulting in the deaths of hundreds of Canadian soldiers. Yet, they persevered, capturing the town of Falaise on August 16 and continuing their advance toward the encirclement.

By August 19, the gap between the Canadian and American forces had narrowed to just three miles. Canadian and Polish troops made a final push to link up with Patton’s forces, and on that fateful evening, at 7:20 PM, a Polish officer and an American lieutenant shook hands in the town square of Shamba. The gap was officially closed, and the Filets pocket was sealed.

Patton’s Claim

While the Canadians and Poles celebrated their hard-won victory, General Patton was not far behind. In his report to Eisenhower, he claimed credit for sealing the gap, emphasizing the achievements of the Third Army while downplaying the contributions of the Canadian and Polish forces. He wrote confidently that his army had destroyed the German 7th Army, seeking to erase the significant sacrifices made by the other Allied forces.

Eisenhower, however, was acutely aware of the truth. He had seen the intelligence reports, the casualty figures, and the battle maps. He understood that it was the Canadians and Poles who had borne the brunt of the fighting and had ultimately closed the gap. Patton’s desire for glory was a dangerous distortion of history, one that could undermine the contributions of the very allies who had fought alongside American troops.

The Dilemma of Leadership

Eisenhower faced a difficult choice. He could allow Patton’s version of events to become the official narrative, preserving the general’s reputation but betraying the memory of those who had fought and died. Alternatively, he could confront Patton, risking a political firestorm that could disrupt the fragile alliance between American, British, and Canadian forces.

The stakes were high. The outcome of the war depended not only on military victories but also on national prestige. The narrative of who won battles would shape post-war negotiations and influence which nations would sit at the peace table. Eisenhower knew he had to honor the sacrifices made by the Canadians and Poles while maintaining the unity of the Allied command.

The Confrontation

Between August 24 and August 25, Eisenhower called Patton to Supreme Headquarters for a private meeting. The encounter took place behind closed doors, and no official record was created. However, those briefed afterward described a tense confrontation. Eisenhower laid out the facts, emphasizing that it was the Canadian and Polish forces who had closed the gap and paid the highest price.

Patton’s reaction was predictable. He felt insulted and frustrated, believing that his contributions were being overshadowed. In his diary, he expressed his displeasure, claiming that Eisenhower was demanding he give credit to the Canadians and labeling it as “damn politics.” Despite his bravado, Patton had to modify his report to reflect the truth of the situation.

Eisenhower’s insistence on accuracy over personal glory marked a pivotal moment in Allied leadership. He understood that the historical record mattered. The men who had fought and died deserved recognition for their sacrifices, and the integrity of the Allied coalition depended on fairness and honesty.

The Aftermath of the Battle

As the battle for the Filets pocket concluded, the consequences were staggering. By August 21, over 50,000 German soldiers had been captured, and the remnants of 15 German divisions had been destroyed. The successful encirclement significantly weakened the German Army in France, paving the way for the liberation of Paris just days later.

However, the aftermath also revealed the emotional toll of the battle. Canadian and Polish soldiers felt a mix of exhaustion, satisfaction, and rising anger as they learned of Patton’s claims. General Harry Krar of the Canadian Army wrote to General Montgomery, insisting that the historical record must accurately reflect the contributions of his forces. He refused to accept obscurity for the sacrifices made by his men.

The Polish forces, having suffered significant casualties while holding Hill 262, shared similar sentiments. They understood that their contributions could easily be forgotten, especially in the shadow of Patton’s fame.

A Legacy of Recognition

In the years following the battle, the struggle for recognition continued. Eisenhower’s intervention ensured that the contributions of Canadian and Polish forces were acknowledged in official reports and public statements. The battle of Filets became a defining moment in Canadian military history, solidifying their reputation as capable commanders on the world stage.

As time passed, the stories of the soldiers who fought at Filets became part of the national consciousness in Canada and Poland. Memorials were erected, and the sacrifices made during the battle were honored in ceremonies and educational programs. The legacy of the Filets pocket served as a reminder of the importance of accurate historical representation and the need to honor all who fought for freedom.

In the end, the battle of Filets was not just a military victory; it was a testament to the power of truth and the necessity of recognizing the contributions of all allies in the fight against tyranny. Eisenhower’s leadership in confronting Patton and ensuring that the sacrifices of Canadian and Polish soldiers were honored stands as a model for coalition warfare, reminding us that history belongs to those who fight for it, not just those who seek glory.