🇺🇸🇺🇸🇺🇸German Child Soldiers Escaped the Camp in Arizona — Just to Go to the Movie Theater and Come Back

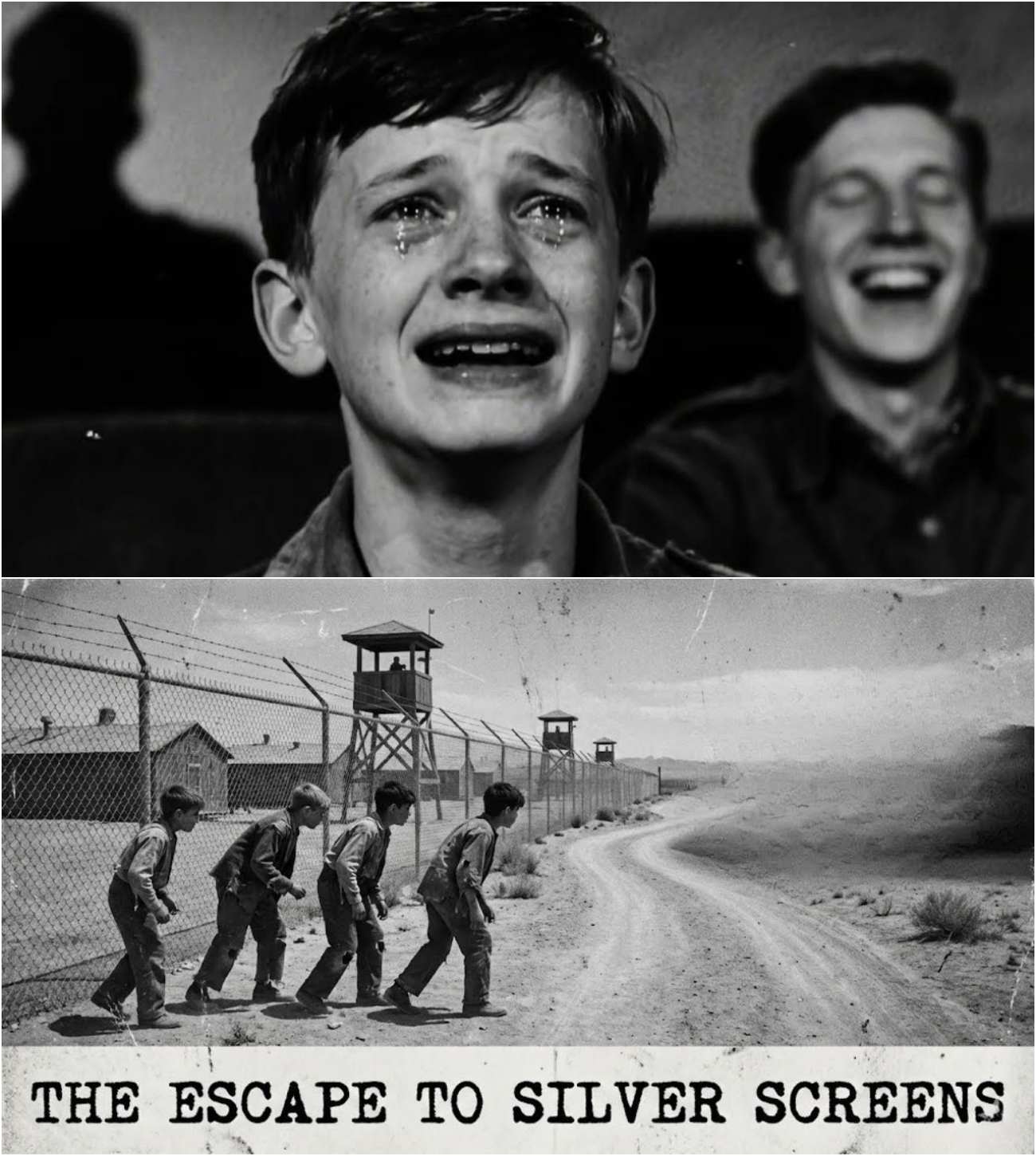

In the midst of one of the most brutal wars in history, three young German soldiers made an escape that would baffle the military command, challenge the conventional wisdom of wartime desperation, and reveal something deeply human about the nature of captivity and freedom. On November 12th, 1944, three teenage prisoners of war at Camp Papago Park in Arizona made a decision that would shock the guards, defy the expectations of their captors, and ultimately remind the world that even in the darkest times, humanity persists.

They didn’t flee to freedom. They didn’t make a desperate run for safety. Instead, these three boys—just 15, 16, and 17 years old—slipped away from their prison camp, walked through the desert, snuck into a movie theater, and watched a double feature. Then, after two hours of being just ordinary boys, they returned to their barracks as if nothing had happened. This wasn’t a story of escape; it was a story of reclaiming something as simple as the right to be human.

The Camp and Its Young Prisoners

Camp Papago Park, located just outside Phoenix, Arizona, was home to some of the most unusual captives in the entire war. By 1944, the United States had over 370,000 Axis prisoners of war scattered across the country. Most of them were seasoned soldiers—hardened men who had fought in North Africa, Sicily, and Italy. But at Papago Park, there was a different kind of prisoner: boys. These weren’t hardened veterans or battle-tested officers; these were teenagers, many of them barely out of childhood, conscripted into the German military and sent to fight on the front lines.

Among these young soldiers were Hans Miller, 16; Friedrich Becker, 17; and Kurt Hoffman, 15. Captured during the Italian campaign, they were brought to Arizona, sunburned and hollow-eyed, still wearing uniforms that hung loosely on their teenage frames. They were placed in a barracks with 40 other prisoners, where life was monotonous and filled with boredom. Despite the harshness of their captivity, the conditions at Papago Park were relatively mild by wartime standards. The Geneva Conventions were strictly enforced—prisoners received three meals a day, medical care, and educational opportunities. Many of the American guards were older men, some deemed unfit for combat, and they often treated the young prisoners with pity rather than hostility.

But the children were still prisoners. They were far from home, cut off from their families, their futures uncertain. And the world outside the camp—the world they had left behind—felt impossibly distant.

A Glimpse of Normalcy

Though their lives were confined to the barracks and the camp’s gardens, the boys still had moments where they caught glimpses of the world beyond. Every Saturday, the nearby town of Scottsdale came alive, and the sounds of laughter and music drifted across the desert. Marcel and his friends could see the lights of the town from their prison camp. They could hear the faint hum of activity—the bustling streets, the glowing neon signs, and the sound of people enjoying their evening.

It was these moments, these fleeting glimpses of normal life, that planted a seed of rebellion in Hans Miller’s mind. He was the first to suggest it, almost as a joke: “What if we just walked into town? What if we saw a movie?” His friends laughed it off, at first. Kurt thought it was insane. But as the days passed, the idea grew in their minds, fed by the boredom of their routine and a deep, yearning desire to feel like human beings again, if only for a brief moment.

They weren’t trying to escape—they weren’t planning to flee to Mexico or to disappear into the desert. They just wanted to experience something simple, something that had been stripped from them. They wanted to be children again. They wanted to laugh, to forget about war for just a few hours. They wanted to watch a movie, like any other teenager.

The Plan and the Escape

On November 12th, the plan was set into motion. The boys went through their usual routine: morning roll call, work in the garden, English lessons, and then, as the evening sun began to set, they prepared for their mission. The evening roll call came, and as the guards checked in the prisoners, Hans, Friedrich, and Kurt slipped away from the barracks, moving quickly and quietly toward the gap in the fence near the southeastern corner of the camp. The escape wasn’t difficult. The guards, for the most part, had grown complacent. They didn’t expect three young prisoners to try to break out, let alone sneak off to the nearest movie theater.

The boys crawled through the gap, making their way into the desert. The siren wailed in the distance, signaling their absence, but they were already far enough away that the search would not catch them before they reached their destination. They jogged toward Scottsdale, hearts pounding with fear and excitement, knowing that they weren’t just running from captivity—they were running toward something else, something they had not experienced in over a year: normalcy.

The Movie Theater

They arrived in Scottsdale shortly after 8:00 p.m. The neon lights of Main Street were a stark contrast to the harsh desert around them. The Valley Theater was alive with activity, its marquee glowing with lights announcing the films: Going My Way starring Bing Crosby, followed by a western. It was a world they had nearly forgotten. They had no money, no plan beyond seeing the movie, but fortune smiled on them that night. The exit door of the theater was propped open, likely by an usher taking a break.

They slipped inside and found seats in the back. The air smelled of popcorn and candy, the dim lighting gave them cover, and as the film started, they were no longer soldiers, no longer prisoners. They were just boys watching a movie. For the first time in months, they weren’t burdened by the weight of war. They weren’t prisoners of war—they were children in the dark, watching heroes on the screen.

As Bing Crosby sang on screen, the boys allowed themselves to laugh. They had forgotten what it felt like to simply be. They watched the film in its entirety—two hours of normalcy. When the credits rolled, and the lights came back on, the reality of their situation returned. They hadn’t escaped. They hadn’t run away. They had simply stolen a few hours of peace.

The Return to Captivity

After the movie ended, the boys slipped out the same back door they had entered. The streets of Scottsdale were quieter now, the night growing colder as they retraced their steps back to Camp Papago Park. They knew they couldn’t stay away. It wasn’t fear that brought them back—it was a promise. They weren’t trying to escape; they just wanted a brief taste of what it felt like to be free again.

When they returned to the camp, they walked straight up to the guard post and stood there, shivering and covered in dust. The guards, still in shock, didn’t know whether to laugh or shoot. Sergeant Clayton approached them slowly, rifle in hand, but with no intention to harm. “Where the hell did you go?” he asked, bewildered.

“We went to the movies,” Hans replied, his voice calm despite the absurdity of the situation.

The three boys were quickly returned to their barracks, where they were confined to solitary for two weeks and lost their work privileges for a month. But Colonel Harold Davies, who was overseeing the camp, understood something others did not. These weren’t hardened enemies. They were children. And in that absurd moment, he saw something profound: even in captivity, even in the heart of war, there is a part of the human spirit that yearns for normalcy. For laughter, for beauty, for a brief escape from the horrors of the world.

The Legacy of Three Boys and Their Night of Freedom

The story of the three boys who escaped to watch a movie may seem like a small, inconsequential moment in the grand scale of war. But it represents something far more significant. It shows that, even in the darkest of times, humanity cannot be fully suppressed. The desire for normal life, for simple joys, for freedom, persists. These three boys didn’t change the course of history or strike a blow for freedom, but they proved something invaluable: even behind barbed wire, even in the midst of war, people will always hunger for light.

When the war ended, and the boys were repatriated to Germany, they returned to a shattered nation. But they carried with them the memory of that night—the memory of being boys again, even if just for a fleeting moment. In the years that followed, the story of the three boys in Arizona became a footnote in the history of World War II, a strange and beautiful tale of resistance—not in the traditional sense, but in the quiet, tender way that only children can resist.