“We Couldn’t Stop Eating” – German Women POWs Burst Into Tears Over First American Fried Chicken

June 12, 1945, Camp Hearn, Texas. In a small, dusty camp nestled in the heart of rural Texas, twenty-three German women prisoners of war stood at the edge of a moment that would change their lives forever. These women, survivors of the brutal and destructive force of Nazi Germany, had just been freed from the horrors of war, only to find themselves thrust into an even more terrifying unknown. They had been told countless times, both by their government and the endless stream of propaganda, that Americans were brutal—merciless, vengeful, and savage. What awaited them in America’s POW camps, they believed, would be a continuation of the violence and cruelty they had endured.

But what greeted them at Camp Hearn that day was not the harshness they had been taught to expect. Instead, it was something so profoundly shocking, it would shatter everything they had ever believed about their enemies.

The truck that carried the women to Camp Hearn groaned to a stop in the sweltering Texas heat. The doors creaked open, and they stepped into an air thick with humidity, the dry land stretching out before them. Barbed wire fences encircled the compound. Armed guards stood at every corner. This was the reality they had expected: a prison camp designed to contain the vanquished enemies of the Reich.

But what happened next defied everything they knew.

After the long journey from Europe, the women were ushered into the camp, where they were greeted not by the shouting of guards or the cold stare of their captors, but by a small but distinct gesture—a table piled high with the most incredible sight they had seen in years: a feast. Golden fried chicken, crispy and glistening under the harsh Texan sun, mashed potatoes swimming in butter, warm biscuits, and gravy boats that seemed to be filled with an abundance they hadn’t imagined possible.

The women stood frozen, their eyes wide, their hands trembling. They had been starved for years. Their bellies had been empty for as long as they could remember. Yet here, in the camp, a meal was laid before them, prepared by the very people they had been told to fear, and even hate.

It was too much to process. They had been told that Americans were monsters, people who would make them suffer for the things their country had done. Instead, they were met with a feast, a simple meal prepared with care by soldiers who looked, and acted, like they were doing their duty, not seeking vengeance. The shock of it was too much to handle. And so, they broke down in tears.

Not from pain or fear, but from overwhelming gratitude, confusion, and guilt. For years, they had been told that their enemies were less than human, and yet here they were, being treated with more respect and kindness than they had ever known.

Among them was Elsa Brandt, a 24-year-old radio operator who had been captured in the final weeks of the war near the Belgian border. Like the others, she had heard the horror stories. She had been told that the Americans would work them to death, starve them, and treat them with the same cruelty they had been taught to expect. Instead, she found herself sitting at a table with other women who had been prisoners for years, staring at the meal before them with disbelief.

They had all heard the stories about how American soldiers had been brutal toward the Germans, how they had shown no mercy. But as Elsa looked around at the faces of the soldiers standing quietly by the kitchen, all she saw was something completely unexpected. They weren’t monsters. They were just people, people doing their job, uncomfortable with their role in this strange new world where enemies became neighbors.

As the women hesitated, unsure of how to proceed, a young private named Virgil Thatcher, barely old enough to shave, stepped forward. He had been on duty during their arrival, his nervousness apparent, but his actions were gentle, almost kind. Without a word, he brought over extra water cans for the women who looked pale and exhausted from the heat. His gesture was small but meaningful. No one expected it. Elsa noticed it, and it troubled her deeply. It didn’t fit the narrative they had been taught to believe.

Over the next few days, more small but significant gestures followed. A corporal named Caldwell, who seemed just as uncomfortable as the women, began learning basic German phrases. He fumbled with his words, but the effort was undeniable. He tried, even if it was just to ask how they were doing or offer them a smile. They couldn’t understand it. They weren’t supposed to be treated like this. They were supposed to be enemies—monsters, even.

And then, the meal came.

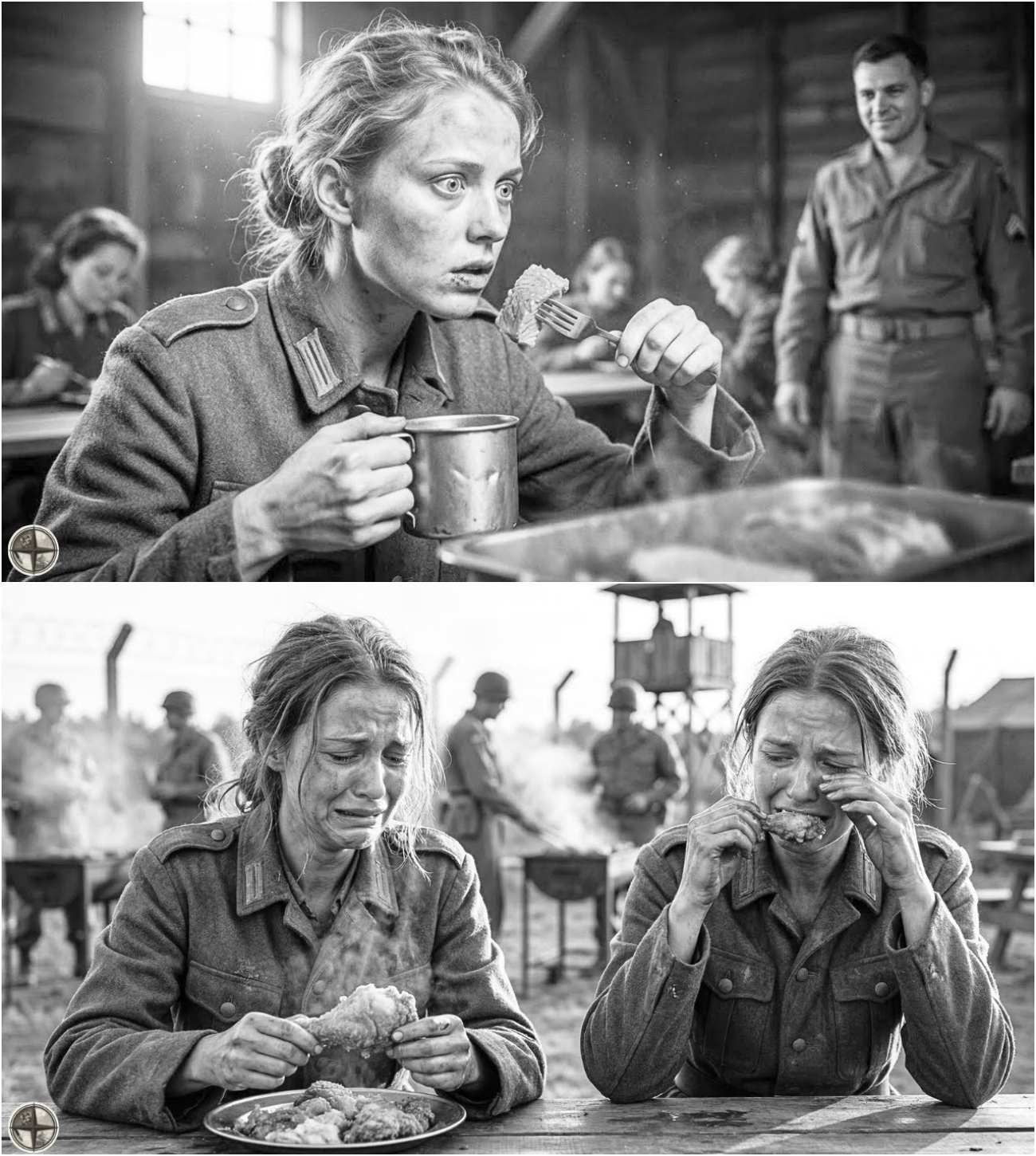

Sunday afternoon arrived with the scent of something completely unfamiliar—fried chicken, the kind that reminded Elsa of a home she had long since lost. The food was rich, comforting, and everything they had been deprived of for years. The women could hardly contain their hunger. They ate as if they hadn’t seen food in years, unable to stop themselves. The grief and confusion that had built up over the last few days finally gave way to something else: a deep, aching hunger, not just for food, but for the kindness they had never expected.

The meal stretched for two hours. The women wept as they ate, their sobs muffled by the bites of chicken and mashed potatoes. Each one of them had faced unimaginable hardship, but this was different. This meal, this kindness, challenged everything they had been told about the world. They had been taught to fear Americans, to believe they were no better than animals. Yet here they were, sitting at a table, sharing food, and finding something they never thought they would find: humanity.

Elsa later recalled this moment in a letter to her family, a letter that would survive the decades and be passed down through the generations. “We cried because we were hungry. We cried because we were confused. But mostly, we cried because everything we believed about our enemies turned out to be wrong.”

The women at Camp Hearn could not have known it at the time, but this meal would change their lives forever. It was not just the food—it was the understanding that what they had been taught was a lie. The reality of war, the reality of humanity, was far more complex than any of them had ever imagined.

That night, Elsa lay in her bunk, staring at the ceiling, haunted by a question that would stay with her for years to come: “What else had we been wrong about?” The walls of fear and hatred built by Nazi propaganda began to crack, and for the first time, Elsa and her fellow prisoners began to question the narrative they had been taught. Could it be true that the Americans weren’t their enemies? Could it be that they, too, were human?

The following weeks would test their courage and resilience. The women of Camp Hearn would go on to rebuild their lives, some choosing to stay in America, others returning to Germany. They faced suspicion, hostility, and guilt for their involvement in the Nazi war machine. But over time, they proved that transformation was possible, that even former enemies could learn to live in peace.

But for Elsa Brandt and the others, that plate of fried chicken would forever remain a symbol of the humanity they had discovered in a place where they least expected it. And in the end, it was this meal—this simple act of kindness—that showed them the most powerful weapon of all: the ability to change, to forgive, and to begin again.