German Child Soldiers Braced for Death in Minnesota — But Americans Treated Them Like Sons

December 14th, 1944.

Reamer, Minnesota.

A military transport truck shuddered to a halt outside a snow-covered logging camp deep in the North Woods. The engine ticked in the cold. Pine trees stood like dark pillars against a sky the color of iron.

American guards stepped forward, rifles ready, breath fogging in the bitter air. They were braced for hardened enemy combatants—scarred veterans, men who had learned to kill without blinking.

The canvas flap peeled back slowly.

What emerged stopped every man cold.

Not soldiers.

Children.

Twelve boys stumbled into the snow wearing Wehrmacht greatcoats that dragged behind them like shrouds. The oldest was fourteen. Most looked younger. Their faces were hollow, eyes sunken so deeply they seemed like skulls wrapped in pale skin.

They shivered violently—partly from cold, mostly from fear.

One boy, barely thirteen, leaned toward another and whispered in German. His voice carried just far enough for a guard to catch it.

“This is the American Siberia,” he said. “We will freeze and die here.”

He spoke with absolute certainty—the kind that doesn’t come from experience, but from propaganda repeated until it becomes truth.

And in that moment, standing in subzero cold thousands of miles from home, those boys believed their war had ended in the cruelest way imaginable.

They had no idea they were about to experience something that would shatter everything the Third Reich had taught them.

Before we continue: if you’re drawn to hidden chapters of history like this—stories where propaganda collides with reality—like, subscribe, and comment where you’re watching from. It helps keep these stories alive.

To understand how children became prisoners of war in a Minnesota forest, you have to understand Germany in late 1944.

The Third Reich wasn’t collapsing slowly. It was imploding—a frantic spiral that devoured everything in its path.

In the east, Soviet forces pushed through Poland toward Germany itself. In the west, Allied armies had liberated France and were driving toward the Rhine. German cities burned under waves of bombers. The “thousand-year Reich” was dying in its twelfth year.

Germany’s response was not strategic.

It was desperate.

In September 1944, Hitler issued decrees that pulled ever-younger bodies into uniform. The Volkssturm—supposedly men sixteen to sixty—became, in practice, anyone who could stand upright and hold something shaped like a rifle.

By November, boys as young as twelve were issued weapons and uniforms sized for grown men. Training was brief—sometimes two weeks, sometimes less. Many never fired their weapon until they faced the enemy. Some never fired it at all.

The Hitler Youth, once a patriotic organization of camping trips and folk songs, became a recruitment pipeline. Boys who had hiked and sung were now digging tank traps with frozen hands, manning anti-aircraft guns against formations of B-17s.

And the propaganda followed them like a shadow.

It said Germany was the victim—surrounded by enemies who wanted total destruction. Every sacrifice was noble. Every death was heroic. Anyone who refused was a traitor.

And above all, it said this:

Americans were gangsters in uniform. They executed prisoners for sport. They tortured children for information. They shipped captives to frozen camps in Alaska where work and frostbite finished what bullets didn’t.

“Minnesota is worse,” one officer allegedly told boys like these. “A frozen hell where the sun barely rises.”

So when these twelve boys were captured near the Belgian-German border in early December—thrown into a chaotic unit and then overrun—they surrendered with trembling hands not because they wanted to live, but because they were too exhausted to keep running.

They were terrified of what came next.

Not of imprisonment.

Of monsters.

The journey to America was misery without a single dramatic moment—just suffering stacked on suffering.

First a holding area. Then a ship. Then another train. Then another truck.

Below deck on a cargo ship, the boys huddled together for warmth, sea-sick and silent. One boy named Friedrich kept a scrap of paper with his mother’s address written in careful script—terrified he’d forget the numbers and never find home again.

Another boy, Josef, refused food for days, convinced it was poisoned.

By the time they reached New York and were transferred inland, they looked like ghosts: hollow, quiet, waiting for the end that propaganda had promised.

So when the transport truck finally deposited them outside the Reamer logging camp, the boys expected barbed wire, guard towers, floodlights—visible proof that they had arrived in a place designed to erase them.

Instead, they saw log cabins with smoke rising lazily from stone chimneys.

They saw lumberjacks—American men with axes resting on their shoulders—watching with puzzled curiosity.

This wasn’t a typical prison compound. It was a working logging camp converted to house POW labor because so many American men were overseas fighting. The camp administrators had processed prisoners before.

But not like this.

Not boys.

No one quite knew what regulations applied, or what you were supposed to do with prisoners who looked like they should still be in school.

The guards led them toward a barracks at a slower pace than usual, as if instinctively understanding that you don’t herd children like cattle.

The heavy door swung open.

Heat blasted out from a roaring pot-bellied stove that filled the room with a living warmth. Wool blankets lay folded neatly on bunks. The air smelled of pine sap and coffee—and something baking that made mouths water involuntarily.

A radio in the corner played American swing music softly, notes floating through warm air like a language the boys didn’t understand but somehow recognized as… normal.

One boy would later describe the moment as profoundly disorienting—like waking from a nightmare into someone else’s dream.

But the real shock came at dinner.

Logging regulations required high-calorie meals—three thousand calories or more—because swinging an axe all day in winter burns through a human body like fire through paper.

The camp cook, a gruff Swede named Olsen in this dramatization, didn’t distinguish between American workers and prisoners.

Food was food. Workers needed it. So he served what the contract required.

The boys were led into the mess hall.

They stopped dead at the threshold.

Tables groaned under towers of pancakes. Thick-cut bacon glistened with fat. Scrambled eggs steamed in piles. Fried potatoes with onions. Fresh bread still warm. Real butter. Strawberry jam. And milk—real milk in glass pitchers, thick and cold, not the bluish substitute they’d known in Germany’s final years.

The smell alone felt violent. Not because it was bad.

Because it was impossible.

The boys stood frozen, unable to process what they were seeing. Their minds searched for the trap.

No one fed prisoners like this. Prisoners got thin soup and moldy bread. Prisoners starved. Prisoners suffered because suffering was the point.

A guard—a farm kid from Iowa in this dramatization—noticed their fear and confusion. He picked up a fork, speared a whole pancake, took an exaggerated bite, and grinned wide.

“It’s real, boys,” he said. “All yours. Dig in.”

They didn’t understand the words.

They understood the gesture.

Slowly, cautiously, one boy stepped forward.

Then another.

Then all twelve surrounded the table like wolves around a kill.

What happened next became legend among camp staff—not as comedy, but as heartbreak.

The boys ate like they’d forgotten how to stop.

They ate until they were sick, then ate more.

They cried while they ate—tears streaming down hollow cheeks as they shoved forkfuls of eggs and bacon into their mouths with both hands.

Friedrich whispered to Josef between bites, voice breaking:

“This is heaven. We died on the ship and went to heaven.”

Josef didn’t argue.

He just kept eating, tears dropping into his plate.

Over the following days and weeks, the pattern continued.

Breakfast: oatmeal with brown sugar, eggs, sausage or bacon, toast with butter and jam, sometimes fruit.

Lunch: thick sandwiches with real meat, soup, pie with a crust that flaked.

Dinner: roast chicken or beef, mashed potatoes in gravy, vegetables, cake or cookies.

The boys gained weight quickly. Hollow cheeks filled out. Color returned to gray skin. Their bodies remembered how to be alive.

But psychologically, they waited for the reversal—for the moment someone would laugh and say, Enough pretending. Here is the cruelty.

It never came.

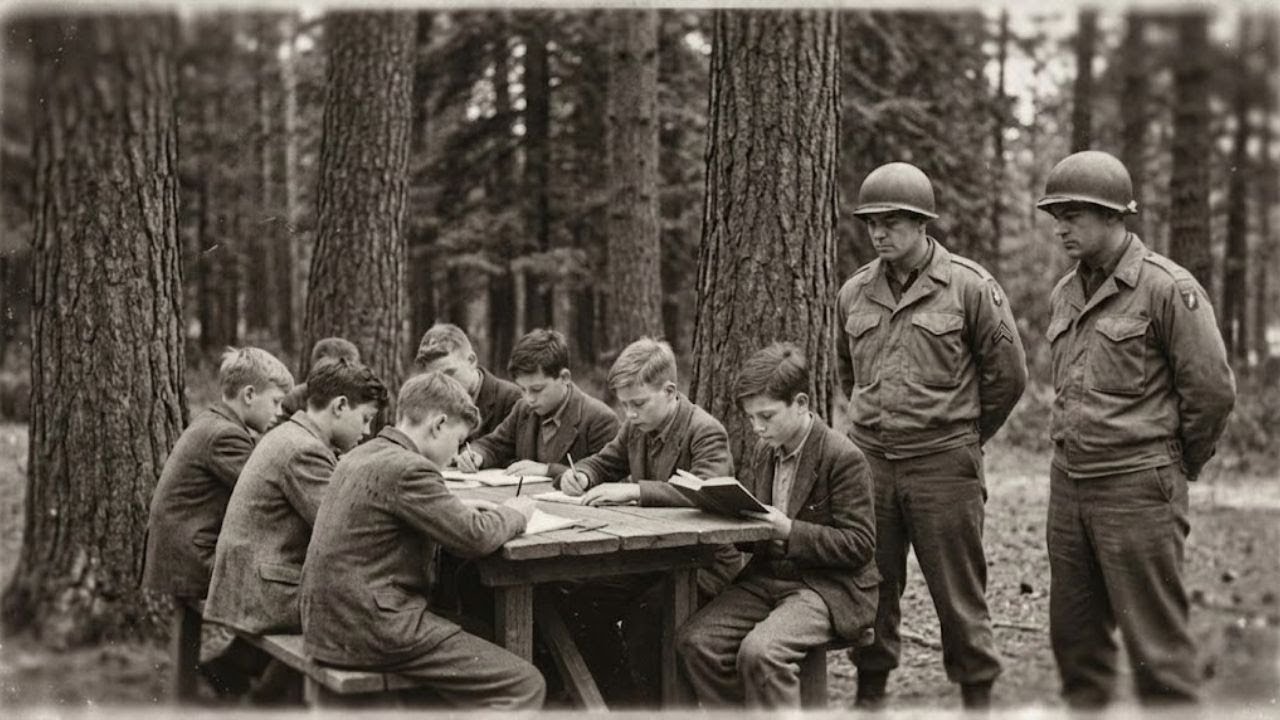

Instead, the lumberjacks began treating them like younger brothers or sons.

These were rough men—mostly Scandinavian-American families rooted in the region for generations—men who knew cold, knew work, knew hunger in the old immigrant stories. They looked at twelve skeletal German boys with haunted eyes and saw something that bypassed politics.

They saw kids.

They started teaching them English phrases during breaks.

“Good morning.”

“Thank you, sir.”

“Pass the salt, please.”

They showed them how to carve small wooden toys during long evenings when darkness came early. One logger—Hank Peterson in this dramatization—spent nights teaching checkers and simple card games.

He never said where his own son was fighting.

The boys never asked.

Some truths don’t need to be spoken to be present.

The work assigned to the boys was intentionally light. They weren’t strong enough for real logging, and no one wanted children doing dangerous labor that could maim or kill.

So they sorted cut wood by size. Carried small tools. Wiped down equipment with oil and rags. Busywork designed to give routine and purpose without exploitation.

The boys approached it with surprising diligence. They had been raised in a culture that worshiped discipline. Even as prisoners, they worked hard because they didn’t know any other way to exist.

But the nights were harder.

Boys woke screaming from nightmares that tore through the barracks like sirens—bombs falling through ceilings, officers shouting orders as retreat turned to chaos, friends dying in frozen ditches with no one to bury them.

The camp physician—Dr. Harold Wittmann in this dramatization—had treated pneumonia and broken bones before.

He had never treated trauma carved into children.

He started sitting with them after dinner, speaking slowly through a translator, letting them talk if they wanted.

Most didn’t.

They just stared into memories they couldn’t escape.

Letters home were allowed under Geneva rules, censored but permitted.

At first the boys wrote cautiously, afraid to say too much, afraid truth itself could be punished.

Then the truth began leaking through in sentences that made censors uncomfortable.

Friedrich wrote to his mother in Hamburg:

“I am not in a prison. I am in heaven. I have eaten more in one day here than in the last month in Germany. I am warm.”

Josef wrote:

“The Americans are not monsters like we were told. They are kind. They feed us. They gave me blankets. I am safe. I pray you are safe.”

The people reading those letters weren’t supposed to feel sympathy for Germans. Not in 1944. Not while American boys died in Europe.

But these weren’t architects of war.

They were children fed into a machine.

And somehow, still alive.

Christmas approached with deepening snow.

Administrators debated what to do. Some argued it was wrong to celebrate while American soldiers fought and froze in the Ardennes.

The lumberjacks disagreed.

They pooled money. Bought warm socks, chocolate bars, oranges wrapped in tissue paper. Carved small toys. Decorated a small tree in the mess hall with popcorn strings and paper chains.

The boys watched in stunned disbelief. They had been told Americans hated Christmas. That Christian traditions were suppressed. That the enemy had no soul.

Yet here were carols—English words on familiar melodies.

That night, Hank Peterson stood and addressed the room. A German-American translator repeated his words carefully:

“We know you didn’t choose this war. We know you were forced to fight for men who didn’t care whether you lived or died. Tonight you’re not prisoners. You’re just boys. And boys deserve Christmas.”

He placed gifts into small hands.

The youngest—twelve—clutched a carved wooden horse to his chest, stared at it as if it might vanish, then broke down sobbing. He had owned a toy horse once, before bombs took everything. He had believed that life was gone forever.

And now it was in his hands again—given by the enemy.

By spring, the boys were healthier, stronger, but their eyes carried a quiet sadness safety couldn’t erase. Their childhoods were gone.

Then the radio announced Hitler’s death, and Germany’s surrender.

Relief mixed with grief and fear.

What would they return to? Were their families alive? Was there a home left to return to?

Repatriation took months. The boys remained in Reamer, suspended between war and peace. The lumberjacks continued their steady kindness—no speeches, no grand gestures, just warmth repeated until it became routine.

In August 1945, the boys boarded trains east.

Men gathered to see them off. Hank shook each hand and held on a second longer.

“Take care now, boys.”

Olsen pressed candy into pockets. Dr. Wittmann waved, eyes red.

The whistle echoed through the pines as Minnesota slid past the windows.

They were going home—to rubble, hunger, grief.

But they carried something the Third Reich had not prepared them for:

They had seen the enemy.

And the enemy had been kind.

Not perfect. Not sentimental. But human.

And that memory—warm meals, a glowing stove, a wooden horse held tight—settled inside them like embers.

Small.

Enduring.

Proof that enemies are made, not born—and that sometimes the most powerful weapon against a lie is not force…

…but a full plate set in front of a starving child.