I. The Boy Soldiers on Oklahoma Red Dirt

In April 1945, the Oklahoma wind carried the smell of dry red dirt and young wheat across the barbed‑wire fence of Camp Wainwright.

Thomas Keller stood on a wooden crate, both hands gripping the wire wrapped around a corner post, trying to see beyond the fields out to the dusty road. He was fifteen, thin, gray‑blue eyes, the German uniform issued to him when he’d been captured now faded, the trouser legs too short at the ankles.

Behind him stretched the long whitewashed barracks, the tired American flag flapping on a pole. In front of him lay countryside he’d never known he could love.

“See anything?” a voice called in German from the ground. Erich, fourteen, slighter, wearing a floppy, stained field cap, squinted up at him.

“Trucks,” Thomas answered. “Two of them. Probably hauling us out to the farms again.”

Erich sighed.

“Still better than the East,” he said. “At least here they don’t shoot.”

“Here,” Thomas said quietly, “people smile at us.”

Both fell silent, remembering.

A year earlier they’d been called Hitlerjugend—Hitler Youth. Stuffed full of speeches about honor, Fatherland, final victory. Issued uniforms that were first too big, then too small, shoved into trenches to replace men who were dead or too exhausted to fight.

Then one day, on the edge of a bomb‑plowed village, they saw something the training manuals hadn’t described: American tanks, American soldiers, black rifles pointing from faces that didn’t look anything like the devils the propaganda had promised.

They were surrounded; “fight to the last bullet” turned into “drop the gun and raise your hands.”

Within two weeks, they’d gone from German woods to a POW transport ship, from German voices booming in their ears to slow Southern English they had to guess from gestures, from European fog to the impossible wide sky of Oklahoma.

Here, people called them “the boys.”

Not monsters. Not heroes. Just boys.

II. The Strange POW Camp in Oklahoma

Camp Wainwright wasn’t the prison Thomas had imagined.

There were guards, barbed wire, watchtowers. But there was also a soccer field, a small library with German books, and nearby farms that hired POWs to harvest wheat, pick cotton, mend fences—paying the U.S. government, while the prisoners received ration coupons for cigarettes, candy, writing paper.

“We’re the strangest prisoners of war in the world,” Erich said one afternoon as they sat in the yard, knees drawn up, watching the flag’s shadow stretch across the red dirt.

“Why?” Thomas asked.

“Because people smile when they hand us shovels,” Erich said. “Because the farmer’s wife gives us apple pie.”

They were first sent out of camp in May, trucked to the Whitmore farm a few miles away. The red‑dirt road cut through green wheat fields, clumps of cottonwoods, idle windmills.

Sitting next to Thomas on the truck bench was a graying American in a plaid shirt and dusty overalls.

“Name’s Hank,” the man said, thumbing his chest. “Hank Whitmore.”

Thomas understood half. He touched his own chest.

“Thomas,” he said, then pointed to Erich. “Erich.”

Hank nodded. “Good workers?” he asked, curling his arm to mime muscle.

Thomas grinned, nodding hard, flexing his own arm in reply.

Hank smirked.

“Good,” he said. “We need help.”

Thomas didn’t catch every word, but he understood enough: the man needed them, not as enemies, but as labor.

Out on the Whitmore fields under the hard sun the Americans called “cool” compared to August, Thomas and Erich learned English by parroting simple words Hank and his wife, Lila, used.

“Bucket.”

“Fence.”

“Wheat.”

“Lunch.”

In the afternoon, when Lila brought food—bread, cold meat, potato salad—she looked at the two blond, blue‑eyed boys propaganda had labeled “the enemy” and saw only children.

“Too young,” she murmured to Hank, standing a few steps away, thinking the boys couldn’t hear. “They’re too young.”

“Same age as the Neilson boy,” Hank said. “If he hadn’t died at Hürtgen.”

Thomas caught “too young,” then “Hürtgen”—the name of a German forest they’d once heard on the radio.

He didn’t understand the whole sentence, but he understood enough: somewhere, American mothers were losing sons in the same woods where his mother waited for news of him.

In the late afternoon, just before the truck came to haul them back, Lila pressed two cinnamon rolls into Thomas’s hands.

“Here,” she said. “For you. And… for your brother.” She pointed at Erich.

Thomas flushed, stumbling over the words.

“Dank—” he cut himself off, correcting. “Thank… you.”

She smiled.

“De nada,” she replied incorrectly, thinking it was German.

Thomas didn’t know Spanish, but smiles look the same in every language.

III. A Letter From Germany and a Nighttime Decision

By August, the war in Europe was over. At Camp Wainwright, news arrived slowly, crookedly, but it arrived: Hitler dead, Germany surrendered, flags hauled down, a nation carved up by lines on paper.

One morning, Thomas was summoned to the POW office. A young American officer stacked a pile of envelopes on the desk, reading off names.

“Keller, Thomas.”

Thomas jerked upright. His first letter from home.

The envelope was crumpled, censor’s stamp smeared, the handwriting shaky—his mother’s.

His hands shook as he opened it, eyes racing across smudged German lines.

His mother was alive. His little sister, Lotte, thin but okay. Their house in Cologne partly destroyed by bombs, but they stayed; there was nowhere else to go. Meals had shrunk. Neighbors had vanished—some dead, some missing, some taken away without explanation.

At the end, his mother wrote:

“If you are alive and reading this, I do not know if you are allowed to come home. But if you are, come back to me. I have nothing left—only you and Lotte.”

Thomas read that one sentence over and over:

“If you are allowed, come back to me.”

That night, the camp fell quiet earlier than usual. The barracks were dark, only the brief ember of cigarettes flaring and fading. Somewhere a harmonica stretched a sad melody through the planks.

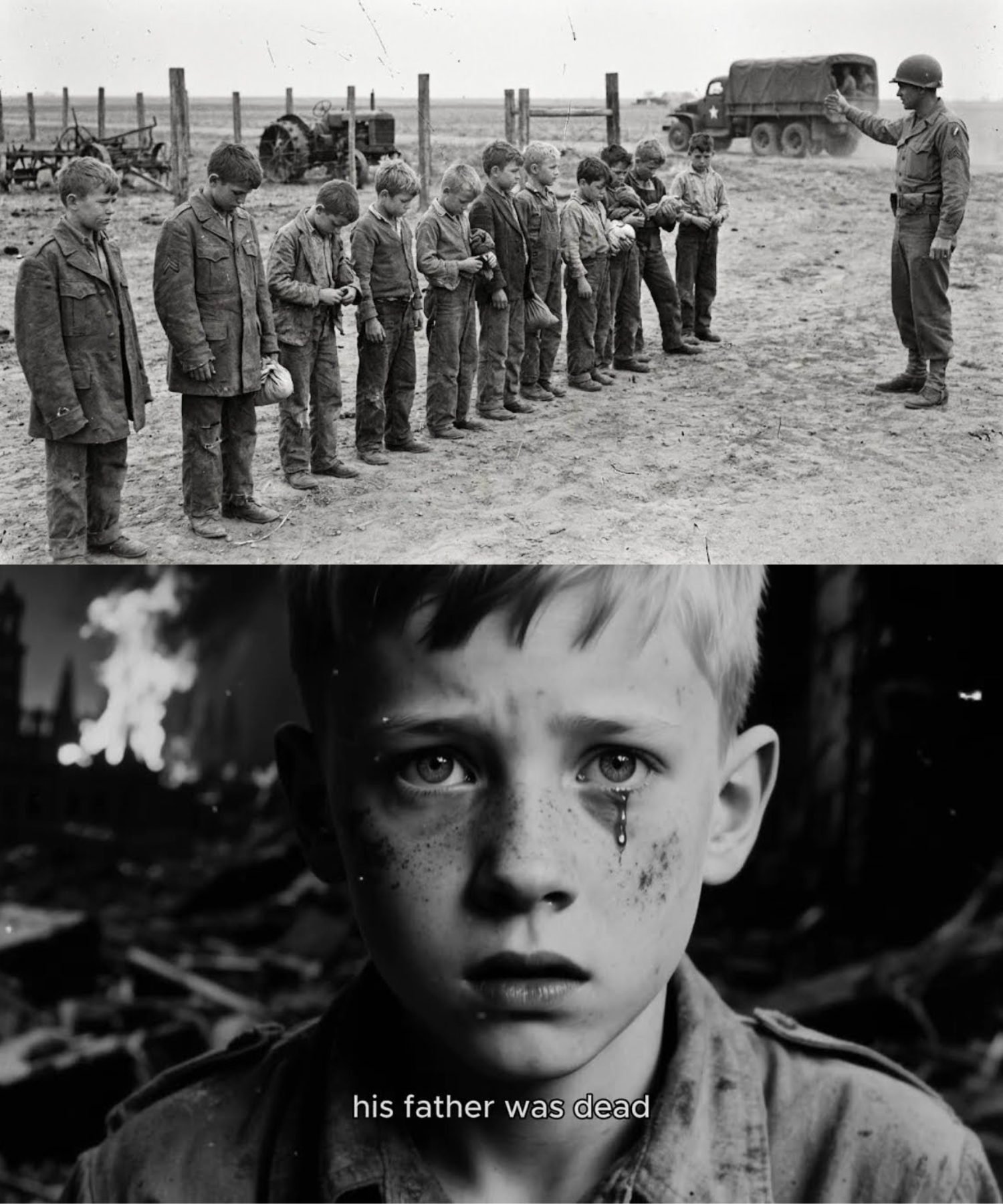

Erich rolled over in the dark, whispering.

“What did your mother say?” he asked.

“The house was bombed,” Thomas whispered back. “But they’re alive.”

Erich was quiet for a long moment.

“As for mine…” he swallowed. “No one wrote.”

He yanked the blanket over his face, voice muffled and tight.

“I don’t know where I’d go, if I had to go back,” he said. “They say my village was burned, my father’s dead, no one knows about my mother.”

Thomas reached across the gap between bunks, groping until he found Erich’s wrist and squeezed.

“You can come to my home,” he said softly. “My mother will take you.”

“If there’s still a home,” Erich snorted.

For a long while, only the wind sighed through the cracks.

“Thomas,” Erich whispered again, “do you want to go back?”

The question hung between them.

Thomas closed his eyes. He remembered his mother, his sister, the stone streets and little church, the smell of baking bread, winters that were cold but familiar. But he also saw Oklahoma red dirt, wheat fields, Hank’s weathered face, Lila pushing an extra slice of pie toward him.

Here, he was a prisoner. But he’d never gone hungry. No one shouted that there was only “victory or death.” No one demanded he be a hero. He was allowed… to be a boy.

“I don’t know,” Thomas whispered. “Half of me wants to go home. The other half…” he trailed off, startled by his own thought. “…the other half wants to stay here forever.”

Erich huffed a soft laugh.

“We really are the strangest prisoners in the world,” he said. “If the war ends and we don’t want to be released…”

His voice wavered.

“Maybe they won’t let us choose,” he said. “They’ll just haul us to the port like crates. Stuff us on a ship. ‘Return to sender’—a shattered Germany.”

Thomas lay still. In the dark, he heard his own voice whisper something he couldn’t have imagined weeks earlier:

“Then… if they make us go…”

He drew in a long breath.

“…what if we just don’t?”

IV. “We Don’t Want to Be Released”

Rumors moved faster than trucks: inside the camp, the MPs had started reading off names of those slated for “repatriation”—shipments back to Germany in the coming months.

“Some boys are happy,” a teenager said, clutching an envelope. “Some cry. They say there’s nothing left when you get there.”

By week’s end, it blew up during a hastily called assembly in the yard. Captain Harris, the American camp commander, stood on a wooden step with a clipboard. Behind him were a few officers; below him, hundreds of German prisoners, most of them too young to be called men.

“The war in Europe is over,” Harris said in clear, slow English. A German interpreter echoed it. “Under the convention, all prisoners of war will gradually be repatriated. Many of you have looked forward to this day. But I’ve also heard…” he glanced over the restless faces, “…that many of you are afraid to go back.”

The interpreter repeated his words. A wave of murmurs passed through the crowd.

Thomas stood shoulder to shoulder with Erich. Erich whispered:

“This is it.”

Thomas’s heart hammered. He nodded, inhaled.

Captain Harris went on.

“The United States does not have a policy of ‘keeping deserters,’” he said. “We do not keep POWs as slaves after the war. You will be returned to your country. That’s the law.”

The interpreter finished; the murmurs grew louder. Hands shot up. Voices cried “Nein! Nein!” over each other.

Suddenly, a voice broke through in halting but loud English:

“I– don’t– want– to– go back!”

The yard fell still. Heads turned.

It was Thomas, fists clenched at his trousers, face flushed but eyes steady.

Harris frowned.

“Son, this is not a—” he caught himself, slowed down. “It’s not a choice.”

Thomas swallowed, frantically arranging English in his head.

“Germany is…” he groped for a word, snapping an imaginary branch in the air. “Broken. Bombs. No food. No… home.”

He pointed at the ground.

“Here… we work. We eat. We learn. Nobody…” he hesitated, then chopped his hand like a gunshot. “Nobody shoots us if we say wrong thing.”

A couple of officers behind Harris exchanged glances.

Another German voice chimed in, this one Erich’s, his English shaky but desperate:

“I have… no house. No family.” He touched his chest. “If I go back… I go to nothing.”

Other hands went up. Other boys, freckled faces with hollow eyes, began shouting in both languages:

“Wir wollen nicht zurück.”

“We don’t want to go back!”

The interpreter hesitated, then turned to Harris. Harris looked out over the scene—a crowd of “enemies” he’d guarded for two years now, hands raised to beg… to stay behind the wire.

Nothing at West Point had prepared him for this.

A guard at his elbow murmured, “Never saw POWs protest freedom day before.”

“Freedom,” Harris muttered, “is more than opening a gate, isn’t it?”

He raised his hand for quiet.

“Listen,” he said, the interpreter trailing him. “I hear you. But I don’t write international law. I can’t just declare you Americans because you don’t want to go back.”

In the crowd, an older prisoner spoke up in smoother English.

“But can we apply?” he asked. “Stay as workers? Immigrants? We can help your farms. Your towns.”

Harris sighed.

“That’s Washington’s business,” he said. “Way above my pay grade.”

But he also knew there were people who’d want to hear this.

V. What Wasn’t in the Rulebook

A week later, a Jeep rolled through the camp gate. A sharp‑looking lieutenant colonel stepped out—Lt. Colonel Marshall, according to his insignia.

In a makeshift conference room, Harris, Marshall, a JAG officer, and a representative from the Oklahoma Department of Agriculture sat around a scarred table.

Harris laid out the situation.

“They’re kids,” he said. “Many of them came in barely old enough to shave. Some have been here two years. They’ve learned English, worked on local farms. The farmers tell me straight: ‘If these boys leave, next harvest is going to be hell.’”

The lawyer frowned.

“Geneva Convention…” he began.

“I know the convention,” Marshall cut in. “We can’t keep POWs after the war. But what if they’re no longer POWs?”

The room looked at him.

“What do you mean?” Harris asked.

“We discharge them as prisoners,” Marshall said. “Send them to the collection points as required. But if a few of them… ‘disappear’ along the way? If some apply for asylum at a state level before they reach the port? If families like the Whitmores sponsor them as laborers, with agricultural paperwork?”

The lawyer’s eyes widened.

“You’re proposing a loophole,” he said. “Something not in the book.”

“The war just tore up your book,” Marshall replied. “Look outside. Europe is one big loophole. And here we’re talking about a handful of boys who want to lug wheat sacks for an Oklahoma farmer.”

The state agriculture representative, a thick‑waisted man who smelled of tobacco, nodded.

“Our farmers are short‑handed,” he said. “If the Feds approve some kind of program—call it whatever you like, ‘trainee,’ ‘resident labor’—I guarantee there’ll be families willing to sign sponsorship papers.”

The lawyer shook his head.

“I can’t officially approve this,” he said. “But… if some files get delayed, if some names are mis‑typed on repatriation lists… it could take years to correct, if anyone even bothers.”

Marshall leaned back.

“Then it seems,” he said, “we may commit a very slow administrative error.”

Harris looked at him—and understood.

“An administrative error with a conscience,” he murmured. “The kind I don’t mind getting chewed out for.”

VI. The Whitmore Offer

One afternoon, when the truck brought POWs out to the Whitmore farm as usual, Hank was already waiting at the gate.

In his hands was a packet of official‑looking papers with a red county stamp.

“Thomas!” he called, turning it into “Tomas.”

Thomas hopped down, dusting his trousers, and trotted over.

Hank clapped him on the shoulder, then waved Erich over.

“Boys,” he said, raising the papers. “Paper. Big paper.”

Thomas took the bundle, scanning dense English text, catching only a few familiar words: “employment,” “residency,” “minor.”

Hank turned to Lila, who stood on the porch shading her eyes.

“Tell them,” he murmured.

She came forward, choosing her words carefully.

“You… can stay,” she said slowly. “Here. With us. Work. Go to school. If government say ‘okay’… we sign. We be…” she frowned, hunting a word. “Family. Maybe.”

Erich stared.

“Stay?” he stammered. “Not– go back– Germany?”

“Maybe no Germany,” Hank said clumsily. “Not now. Later, if you want. When you are… man, not boy.”

Thomas saw his own hand tremble around the papers.

“Why?” he asked in broken English. “Why us?”

Hank exhaled, looking over his fields, then back at them.

“Because you work hard,” he said. “Because you say ‘thank you’ when my wife gives you food. Because my son…” his voice dropped, “…died in a forest in your country. And when I see you boys, I see… him. But alive.”

Lila’s hand tightened on his arm.

“We cannot bring Neil back,” she said, her eyes wet. “But we can keep two more boys from being lost.”

Erich bit his lip.

“People… in town,” he asked, “… they no angry? German?” He touched his chest. “Nazi?”

Hank shook his head.

“Some are,” he admitted. “Some look at you and only see the uniform. But some see kids who can help bring in the wheat. And… some see what this war did to all our children.”

He stopped, locking eyes with Thomas.

“You want to be American?” he asked. “Not on paper, maybe. Not yet. But—” he pressed his hand to the dirt—“in here.”

Thomas’s throat closed. He thought of his mother, his sister, the line “come home if you are allowed.” He saw two roads:

One back to rubble, ration cards, the ruins of a defeated nation.

The other across Oklahoma red earth, where a family who’d lost a son would call him “son” if he stayed, learned a new tongue, turned into something in‑between—not fully German, not fully American.

“If I stay…” he turned to Erich, slipping into German, “what about you?”

Erich looked at the sky.

“If you go, I go,” he said. “If you stay, I stay. I don’t have any ‘home’ but the one I build myself now.”

Thomas faced Hank again, clutching the packet like a life ring.

“Ja,” he said, then corrected himself. “Yes. I… want… stay.”

Hank didn’t catch every word, but he understood enough. He extended his hand.

“Then let’s go make trouble for the paperwork,” he said.

VII. Departure Day — and the Missing Names

In October 1946, a convoy of trucks rolled out of Camp Wainwright toward the rail depot where trains waited to carry German POWs to the port.

Inside the camp, the barbed‑wire yard looked emptier. Beds in the barracks sat unclaimed. Names called over the last weeks no longer answered at the soccer pitch, the library, the mess hall.

Thomas and Erich stood at the gate, each with a small bag—spare clothes, a photograph of the Whitmores, a couple of English primers.

Captain Harris approached with a clipboard.

“Keller, Thomas,” he read loudly, then paused. “Erich—” he squinted at the paper, brows knitting. “Erich… I don’t see his last name here.”

The JAG officer would have called it “a clerical error.”

Harris repeated Thomas’s name to be sure.

“Keller, Thomas.”

Thomas stepped forward.

“Yes, sir,” he said.

Harris looked at him for a long moment.

“Private Keller,” he said in German, “do you understand that you are voluntarily not returning to Germany with the others? There is no guarantee your paperwork will go smoothly. It may take years. You may always be the ‘German boy’ in some people’s eyes, not an Oklahoma farmer.”

Thomas nodded.

“Yes, Herr Captain,” he said. “But there…” he gestured vaguely toward the far‑away north of Europe, “…no one is waiting for me. Here…” he pointed toward the dusty road, “…someone calls me ‘son.’”

Harris bit his lip, folding the list.

“I’ve never seen a case like yours,” he said. “In my report, they asked: ‘Is there a security risk? Are they dangerous?’”

He glanced at both boys.

“I answered: ‘They are only dangerous to your own hatred if you insist on treating them as enemies after they’ve put their guns down.’”

He held out his hand.

“Good luck, Thomas,” he said. “The United States isn’t necessarily heaven. But it is a place where some people get the chance to be something other than their past.”

Thomas shook his hand hard.

“And… thank you, sir,” he said in English. “For… mistake on list.”

Harris’s mouth twitched.

“War lists get a lot of important things wrong,” he said. “Sometimes it’s good when they’re wrong in a humane direction.”

The convoy rattled off toward the station, carrying hundreds back to the port. In the railcars, many waved through the slats at those who stayed.

By the camp gate, an old pickup waited. Hank Whitmore sat behind the wheel, cap low over his brow. Lila was next to him, holding a new wool coat in her lap.

When Thomas and Erich stepped through the gate, no longer POWs but something undefined and new, Hank opened the truck door and scooted over.

“Get in, boys,” he said. “The wheat won’t harvest itself.”

Erich looked back at the gate one last time. Behind it lay a past he’d arrived in without choice. Ahead was a future he was choosing, with no guarantees.

He climbed into the truck.

VIII. Years Later: “The Town’s German Old Men”

Years passed.

It wasn’t all smooth. There were suspicious eyes. Whispers at the café: “Those are the old Germans.” Paperwork stalled sometimes, demanding more proof, more signatures.

But there were also harvest seasons where Thomas and Erich worked themselves ragged in the fields, got paid, paid taxes, had their names in the county books like any other laborers. There were evenings in adult‑education classrooms, sitting younger than their classmates in age but older in their eyes, tracing English letters by lamplight.

Thomas sent money back to Germany, eventually saving enough to bring his mother and Lotte over, under family‑reunification provisions. When they arrived at the little Oklahoma station, Lila hugged Thomas’s mother like an old friend.

Erich had no one to send for. But the Whitmores never asked for more. They just set an extra place at the table every Thanksgiving and hung an extra stocking by the fireplace each Christmas.

When the Korean War broke out, someone asked whether Thomas and Erich would enlist in the U.S. Army “to prove their loyalty.” Thomas shook his head.

“I’ve already walked through one war wearing the wrong uniform,” he said. “Now I’d rather build things than break them.”

Erich became a mechanic in town, specializing in tractors. Thomas eventually opened a small farm‑equipment shop. Their accents mixed Oklahoma twang with German consonants, so outsiders heard they “weren’t from around here,” but locals were surprised at how well they knew every drought year, every family farm.

Kids in town grew up knowing them just as “Mr. Thomas” and “Mr. Rick”—the two German old guys who argued about whether Lila’s apple pie tasted better or worse than it had in 1950.

Sometimes, on rare snowy days when a thin white layer dusted the red soil, Thomas would stand at the edge of a field, staring at the gray sky and thinking of Köln—the smell of rain on paving stones, the sound of church bells.

Erich would wander up and hand him a mug of hot coffee.

“Missing home?” he’d ask in German—a language they now mostly saved for important things.

Thomas thought about it.

“Maybe,” he said. “But which one?”

Erich chuckled.

“Good answer,” he said. “Maybe we’re the rare fools lucky enough to have two homelands.”

Thomas sipped.

“And the strangest ex‑POWs,” he added. “The ones who only became ‘free’ when they decided not to leave the country that captured them.”

Erich nodded.

“That day,” he said, “when you stood in the camp yard and said ‘I don’t want to go back’… if someone had told you that one day you’d be saying to your own kid, ‘American school starts at eight; you’d better not be late’…”

They both laughed.

On the Whitmore living‑room wall—now crowded with pictures of grandkids, farm awards, church crafts—there was still one black‑and‑white photograph: two skinny boys in striped POW fatigues by a camp gate, hands shading their eyes, looking toward an old pickup.

On the back, someone had scrawled, in two languages, shaky but legible:

“1946 – The day the German boys decided not to go home.”

“Der Tag, an dem zwei deutsche Jungen beschlossen, nicht nach Hause zurückzukehren.”

IX. What They Chose to Keep

When Thomas and Erich were old, young reporters started showing up, wanting to write about “the German POWs who once lived in Oklahoma.”

“Is it true you refused to get on the ship back to Germany?” one wide‑eyed journalist asked.

Thomas smiled.

“Not exactly ‘refused,’” he said. “We just… walked out the gate in the opposite direction. There was a farmer waiting. They called it a ‘paperwork problem.’ We called it… luck.”

“Do you feel guilty?” she asked. “That your comrades went back to ruins while you stayed here?”

Erich was quiet a long time before answering.

“Yes,” he said. “Many nights. But then we thought: if we have a chance to live a life that war didn’t steal from us, maybe that’s the best way to honor those who never had that chance.”

Thomas added:

“And if someday a child asks us, ‘How did you know where your home was?’ we’ll say, ‘Home is where you choose to take responsibility for rebuilding, not just where you happened to be born.’”

The reporter paused her pen, looking up.

“Do you ever regret not boarding that ship?” she asked at last.

Erich looked out the window—at Oklahoma fields still stretching gold under the sun, at children shrieking in the yard, at old Lila in the kitchen scolding grandkids for running indoors.

“We regret many things,” he said. “Putting on a uniform too young. Believing things grown‑ups said without asking questions. But about staying here…” He shook his head. “No.”

Thomas nodded softly, adding in German—now reserved for the truest words:

“We were German soldiers who became American men on the same red dirt. If there’s anything strange about that, it’s only that…”

He smiled faintly.

“…the world is bigger than the borders people draw during war.”

And out there, on Oklahoma’s red earth, the story of the German child soldiers who refused to leave America after the war ended never made it into law books or official histories. It lived quietly in the memory of a small town, where people had long since gotten used to calling them something much simpler:

“Neighbors.”