On a chilly February morning in Los Angeles, most people hurried past the city’s invisible souls, eyes averted, hearts closed. But for William Anderson, a former construction worker whose life had unraveled into homelessness, this day would be different. Huddled outside a convenience store in a worn Lakers jersey, William clung to the last shreds of his past—a battered pride, a faded tattoo of the Lakers logo, and memories of better days.

William’s tattoo, a splash of purple and gold ink on his forearm, had been with him for twenty years. He’d gotten it in 2000, the year Shaquille O’Neal and Kobe Bryant led the Lakers to championship glory. Back then, William had a steady job, a family, and a future. But a workplace injury, mounting medical bills, and a cascade of misfortunes had left him with nothing but the ink on his skin and an unbroken love for his team.

Most mornings, William was invisible. People passed by, pretending not to see him. Only Robert Thompson, the kindly store owner, greeted him with dignity and a hot cup of coffee. “You’re looking sharp today, William,” he’d say, offering a smile that made the cold a little easier to bear.

But this morning, as William tried to stay warm, something unusual happened. A large shadow fell across him—not the cold indifference of a passerby, but the presence of someone who truly saw him. William looked up and, for a moment, thought he was dreaming. Standing before him was Shaquille O’Neal himself, larger than life, looking at William, not through him.

“That’s a nice jersey you got there, brother,” Shaq said, his deep voice warm and familiar.

William’s heart pounded. He pulled up his sleeve, revealing the Lakers tattoo. Shaq crouched down, meeting William eye to eye. “How long have you had that tattoo?”

“Twenty years,” William replied, voice rough from disuse. “Got it the year you won your first championship with us.”

A small crowd began to gather. Shaq listened as William shared his story—how he lost his job, his home, and his family, but never his love for the Lakers. He spoke of watching games through sports bar windows, saving up for tickets he could no longer afford, and how basketball had given him hope in the darkest times.

Shaq’s expression changed. Those who knew him could see he was about to do something big, something meaningful. “You know what, brother?” Shaq said, reaching into his pocket. “That tattoo tells me you’re loyal. You don’t give up. Right now, you don’t need a handout. You need a hand up.”

Shaq pulled out his phone and started making calls. He called a construction company manager he knew, a friend who ran a transitional housing program, and his own foundation. Within hours, William’s life began to shift. Paperwork for ID replacement, job applications, and housing programs appeared. A local barber offered a free haircut. Jennifer Thompson from the adult education center volunteered to help William update his construction certifications.

By late afternoon, William was in clean clothes, his hair freshly cut, and sitting in the office of Barbara Williams, the housing program director. The room was small but clean, with a bed, a desk, and a window—a palace compared to concrete sidewalks. Tears filled William’s eyes, not just for the physical comfort, but for the dignity restored to him.

The next day, Michael Davis, the construction manager, interviewed William. Impressed by his experience and innovative ideas, Michael offered him a job, not as charity, but because the company needed someone with his skills. “Get settled, update your certifications, and we’ll hold the position,” Michael promised.

Word of Shaq’s act of kindness spread through the neighborhood. The spot outside the convenience store, once a symbol of despair, became a hub of hope. Robert set up a table with a sign: “Need help? Let’s talk.” Community members brought food, shared job leads, and offered support. The ripple effect grew—other homeless individuals found work and housing, inspired by William’s story.

A month later, the Staples Center buzzed with excitement. Shaq had organized an event to celebrate the community’s transformation. William, now a leader at his construction site and mentor to others, stood backstage, his Lakers tattoo visible beneath his sleeve. Onstage, Shaq spoke: “A month ago, I saw a man with a Lakers tattoo. But what I really saw was loyalty, resilience, and untapped potential. Today, we recognize that these qualities exist in many who just need a chance.”

The event announced new initiatives: 200 companies pledged jobs, a million-dollar fund for training and certification, and a “Talent Bank” to match homeless individuals with opportunities. William shared his story, his voice steady and strong. “A month ago, I was invisible. Today, I’m helping others become visible again. That’s not just change—it’s transformation.”

The Lakers organization, moved by William’s journey, created an annual award to honor those who showed extraordinary resilience and community impact, featuring the Lakers logo that had started it all.

As the crowd dispersed, William stood outside the arena, looking at the stars. His tattoo, once a reminder of loss, had become a symbol of hope and new beginnings—not just for him, but for an entire community. Shaq’s final words echoed in his mind: “We all wear marks of our loyalty, our struggles, our hopes. The question is, are we willing to see them in each other—and do something about what we see?”

Sometimes, the smallest details—a tattoo, a moment of recognition—can spark the biggest transformations. True greatness, William realized, isn’t measured by what we achieve for ourselves, but by how we lift others up along the way.

Shaq’s Lakers teammates recall practice pranks worthy of statue honor

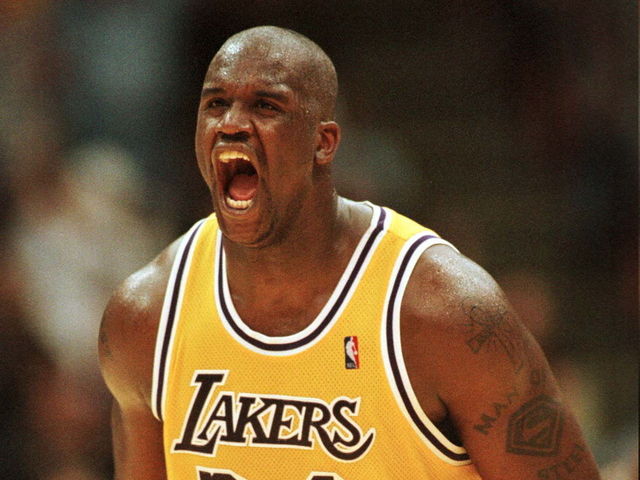

Lakers center Shaquille O’Neal was raw power on the basketball court, but his teammates remember him just as much for his sense of humor and ability to keep them loose during the high pressure of championship seasons. (LUCY NICHOLSON/AFP/Getty Images)

His brute force intimidated anyone who tried to defend him, and his pranks left nearly everyone roaring with laughter.

A dominant big man and a life-long jokester, Shaquille O’Neal brought those traits to every stop during his 19-year NBA career, which included an eight-year run with the Lakers (1996-2004) that yielded too many dunks and jokes to count. O’Neal, who won three of his four NBA titles with the Lakers, will be honored by the organization on Friday when they unveil a statue of O’Neal’s likeness dunking the ball outside of Staples Center prior to their against Minnesota. With his raw power and a larger-than-life personality to match his listed 7-foot-1, 325-pound frame, O’Neal always seemed a perfect fit in the entertainment capital of the world.

Among many memorable moments, O’Neal’s former Lakers teammates have had trouble forgetting one that left them chuckling in horror.

“I’m just scarred by the one where he ran out into the middle of the court naked before practice,” said former Lakers forward Rick Fox, who played with O’Neal from 1997 to 2004. “I can’t get that image out of my mind.”

Neither can other teammates, who recalled O’Neal often reporting to practice wearing his birthday suit instead of a Lakers uniform for one simple reason.

“We had a rule you can’t be late to the center huddle,” said Lakers coach Luke Walton, who played with O’Neal as a rookie in 2003-04. “He got here where he didn’t have time to get his clothes on. So he made sure he was on time in the center circle.”

In case his teammates did not already notice the moment O’Neal walked into the gym, he apparently reminded them again.

“Shaq walked onto the court, put his hands up and said ‘I’m ready to practice,’ said Lakers assistant coach Mark Madsen, who was O’Neal’s teammate from 2000 to 2003. “He had not one inch of clothing on. So he was there in all of his glory.”

The shtick prompted laughter, before turning awkward.

“He would start running around looking for guys to hug. Everybody was trying to get out of the way,” mused former Lakers guard Derek Fisher, who played with O’Neal from 1996 to 2004. “That’s why when I hit that shot in San Antonio in 2004, that’s why we were so good at sprinting off of the court.”

As much as he toed the line with his wardrobe choices before practice started, O’Neal always practiced with his actual uniform. Fox expressed the views of many, saying he’s “not guarding him, not doubling down in the post and digging for the ball” sans uniform. As Madsen mused, “that would’ve been the day I would’ve submitted my resignation papers.”

While that moment remained a vivid memory for better and worse, O’Neal’s teammates said those moments of levity helped break up the monotony of a long NBA season. It also offered perspective.

“We played in a lot of high-pressure situations. But when you’re having fun, laughing and smiling, you’re not really aware it’s a pressure situation,” said Lakers associate coach Brian Shaw, who played with O’Neal on the Orlando Magic (1994-97) and Lakers (1999-2003). “You’re handling your business as a professional. But you’re smiling and having fun doing it. After all, basketball is a game.”

CHANGING THE GAME

And it’s a game O’Neal played well. So after acquiring O’Neal as a free agent in 1996, former Lakers general manager Jerry West offered a bold and accurate prediction as the two walked in the Forum and looked at the championship banners and retired jerseys on the wall.

“Being remembered as an all-time Lakers center is what Jerry West told me I could accomplish,” O’Neal recalled. “If I was to come there, I would put up big numbers, dominate and win championships.”

It took three years for the Lakers to hire Phil Jackson to help O’Neal win his first NBA title. During that time, O’Neal accomplished what his two favorite memories during his time with the Lakers.

He posted a career-high 61 points on his 28th birthday on March 6, 2000 in a designated road game against the Clippers. Beyond wanting to have what Lakers president Jeanie Buss called “one big birthday party,” O’Neal took motivation from former Lakers center Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s presence. As a short-lived member of the Clippers’ coaching staff, Abdul-Jabbar had been critical of O’Neal’s free-throw shooting and failure to win an NBA title.

“When I was coming down, he would look at me,” O’Neal said. “I’m putting in my head, ‘Kareem is not respecting me.’ I have to turn it up a whole other notch.”

O’Neal also cherished Kobe Bryant’s lob to him as the Lakers overcame a 13-point fourth-quarter deficit against the Portland Trail Blazers in Game 7 of the 2000 Western Conference finals. That paved the way for O’Neal’s first NBA title in a Finals win over Indiana. Though the two often had a tense relationship, O’Neal says that game showed how he and Bryant were “the most dominant Lakers 1-2 punch in the history of the game.”

Two more titles followed, with O’Neal earning his second and third Finals MVPs awards against Philadelphia (2001) and New Jersey (2002). While Madsen marveled at the Sixers’ inability to stop O’Neal despite Sixers center Dikembe Mutombo and a swarm of double-teams, Shaw found no one on the Nets team equipped to defend O’Neal.

All of that helped O’Neal become part of the lineage of Hall of Fame Lakers centers, including Abdul-Jabbar, Wilt Chamberlain and George Mikan.

“Shaq could be the last of the great bigs that were so dominant in Lakers history,” Fisher said. “He could be the last one in terms of where the league is going and how the game is being played. We just may not see that type of dominance in the middle ever again.”

But even if Walton saw up close with Golden State how the 3-point shot, smaller lineups and analytics helped change the game, that’s partly because there’s no one in the league right now that created the physical mismatches O’Neal did.

“Small ball wouldn’t work on Shaq,” Walton said. “All the teams that go small, you would have to figure out a new philosophy when you’re playing against him.”

PRACTICE DIDN’T MAKE PERFECT

Walton would know after having the unfortunate task of guarding O’Neal in practice.

“It was impossible. I’m serious,” Walton said. “You felt like you were not an NBA player. It was a feeling of helplessness. Physically, there was nothing I could do. I tried to jump on his back. That was it.”

So, Walton resorted to fouling O’Neal, which only prompted a stern warning.

“He would tell me he was going to punch me if I did it again,” Walton said. “If I didn’t, he’d dunk on me. If I did (foul), then I’d think my life was going to end. I tried my best not to switch on him. I just bumped him and ran back to my own man.”

Madsen was a little more relentless, prompting O’Neal to call him the toughest defender he ever faced in practice. That was all relative, of course.

“You never had success against Shaq. When you were guarding Shaq, it was almost like a flea or a termite against a grizzly bear,” Madsen said. “You don’t stand a chance. You fly around, you flap and do whatever you can. But ultimately, that grizzly bear is going to do what the grizzly bear wants to do.”

BIG HEART

Underneath that rough exterior, though, O’Neal showed a soft spot.

He teased Madsen for his wardrobe choices. So O’Neal bought clothes for Madsen at the Big and Tall store in Beverly Hills. O’Neal despised Madsen’s minivan. So he took him to a Chevy Dealership and took care of the down payment. O’Neal also invited Madsen and his family to a house party.

“Shaq ultimately wanted everyone to go hard, but he was somebody that loved to have fun,” Madsen said. “He was somebody that loved people.”

O’Neal showed that love to Walton too. He took equal offense to Walton’s 1970 Cadillac that he called “pretty beat down and gross.” So O’Neal channeled his inner Xzibit, took Walton’s vehicle to a local auto shop and gave him the kind of upgrade seen in MTV’s “Pimp my Ride.”

“The only thing I didn’t like is they put ‘LW’ on every seat all over the place,” Walton said, chuckling. “I’m not really into that. But he made my car real nice.”

While O’Neal punished defenders who tried to intimidate Walton, O’Neal encouraged Madsen to intimidate defenders. But nothing intimidated anyone more than when O’Neal used his teammates as part of his training regimen with the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Reserve Academy. Who better to use as test dummies for practicing arrests while reciting the penal code?

“He would read you your rights, so he’d remember all that stuff,” Shaw said, laughing. “He’d kick your legs apart and put you up against the wall and pat you down. He was practicing on us. Everyday we would try to hide, because you knew he would try to arrest you.”

O’Neal’s career accomplishments earned him a spot in the Hall of Fame – he was inducted in September – and now the Lakers will unveil his unique statue, which is suspended 10 feet above the ground at Star Plaza.

“It’s going to be nice to see all the guys there and the guys that helped me win a championship,” O’Neal said. “I definitely didn’t do it by myself.”

O’Neal’s teammates can rest easy about one thing, though. When they see O’Neal at his statue unveiling, he will have his clothes on.