“German Women POWs Were Starving in a Train Car for 12 Days — Americans Found Them Half-Dead”

In April 1945, as the world was engulfed in the chaos of World War II, a chilling story unfolded that would reveal the depths of human suffering and the heights of compassion. This is the harrowing account of 89 German women, prisoners of war, who were abandoned in a train car for twelve agonizing days, left to starve in darkness while the world around them crumbled.

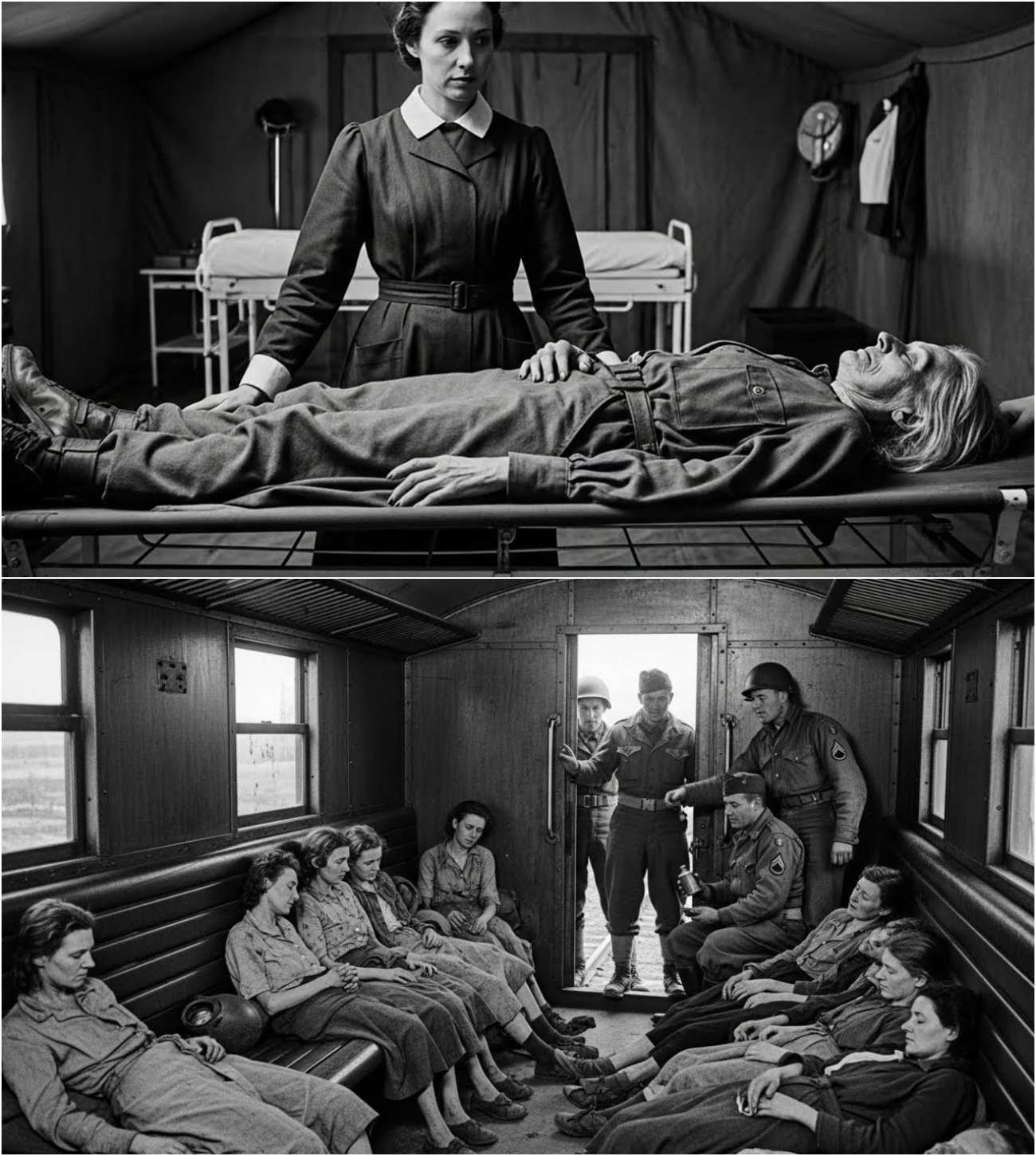

The Train of Despair

As the train rattled through the desolate landscape, the women inside felt the weight of despair pressing down on them. They had been told that the Americans would show no mercy to those who had served the Third Reich. The boxcar, filled with rust and the stench of decay, became their prison. With no food, no water, and no hope, they huddled together in the suffocating darkness, their bodies growing weaker by the hour.

Days turned into a nightmare. The sounds of the outside world faded away, replaced by the haunting silence of death. By the time American soldiers arrived on April 29, 1945, the women were barely clinging to life. Many had succumbed to starvation, their bodies propped against the walls, while the living resembled ghosts, their sunken eyes and cracked lips a testament to their suffering.

A Shocking Discovery

When Private Thomas Riley and his squad pried open the doors of the boxcar, they were met with a scene that would haunt them forever. The smell was overwhelming—a mix of human waste, death, and desperation. As sunlight flooded the interior, the soldiers were struck by the sight of skeletal figures, some barely breathing, reaching out for help. Among them was a young woman, her eyes wide with fear and confusion, who could barely muster the strength to speak.

“Can you speak?” Riley asked, kneeling beside her. Her lips moved silently, but when he offered her water, she grasped the canteen with trembling hands, drinking as if she had forgotten what it meant to be hydrated. It was a moment of profound humanity, a connection forged in the depths of despair.

The Rescue Operation

The chaos that followed was a flurry of activity as medics rushed to the scene, calling for blankets, water, and medical supplies. The women were lifted from the boxcar, many unable to walk, their bodies wrapped in army blankets. As they were taken to a makeshift field hospital, the soldiers worked tirelessly to document the horrors they had witnessed. They took photographs and collected the few possessions the women had managed to cling to during their ordeal.

Among these items was a diary belonging to Margaret Hoffman, a radio operator from Hamburg. Her last entry, written just days before the women were discovered, spoke of desperation and impending death. “No water for four days. Greta died this morning. I think I will be next.” Yet, against all odds, Margaret was one of the 86 women who survived.

A New Beginning

The field hospital, set up in a warehouse district, was a stark contrast to the horrors the women had endured. The smell of antiseptic filled the air as they were treated with care and dignity. Dr. Sarah Mitchell, an army nurse, was among those who tended to the women. She had seen unimaginable suffering in her career, but nothing prepared her for the sight of these women, who had been reduced to mere shadows of their former selves.

As the days passed, the women began to recover physically. They were given food, clean clothes, and a safe place to sleep. Each meal was a revelation—a far cry from the meager rations they had endured. For many, it was their first taste of kindness from those they had been taught to fear.

The Struggle with Identity

However, the psychological transformation was even more profound. The women grappled with the guilt of being cared for by their former enemies. They had been taught that the Americans were cruel and merciless, yet here they were, receiving compassion and care. The contradictions of their beliefs began to unravel.

Margaret, who had once viewed the Americans through the lens of propaganda, found herself questioning everything she had been taught. “If they can see us as human,” she said, “then maybe we need to start seeing ourselves that way, too.” This realization sparked conversations among the women, as they began to share their thoughts, fears, and hopes.

The Screening of Truth

In June, the Americans organized a screening of documentary footage showing the horrors of Nazi concentration camps. As the women watched the images of death and despair, the weight of their past became unbearable. Some wept openly, while others sat in shock, grappling with the reality of what their government had done.

Colonel James Patterson, who had ordered the screening, addressed the women afterward. “I showed you this not to punish you, but because you deserve to know the truth about your government,” he said. “You must decide what you believe.” His words resonated deeply, forcing the women to confront their complicity in the atrocities committed in the name of their country.

A Journey of Healing

As the weeks turned into months, the women continued to heal, both physically and emotionally. They were given the opportunity to work, helping in the camp library, kitchen, and infirmary. Through these activities, they began to rebuild their identities, no longer defined solely by their nationality or past actions.

Margaret found solace in literature, reading stories that challenged her perceptions of the world. She discovered that the Americans, too, had faced hardship and suffering. This realization shattered the walls of propaganda that had confined her understanding of humanity.

The Departure

By August 1945, the time came for the women to return to Germany. The news was met with mixed emotions—some were eager to reunite with their families, while others felt a sense of grief at leaving the safety and kindness they had experienced. Anna Miller, one of the women, expressed her fear of returning to a world that would not understand her journey.

On the eve of their departure, the Americans organized a farewell gathering, filled with food, music, and dancing. It was a bittersweet celebration, a recognition of the bond that had formed between the soldiers and the women they had saved. As they prepared to leave, Margaret approached Dr. Mitchell, her voice filled with gratitude. “You give me back my humanity,” she said, tears in her eyes.

A Legacy of Compassion

As the buses pulled away from the camp, the women carried with them not just their belongings, but also a newfound understanding of humanity. They had been transformed by their experiences, learning that kindness could prevail even in the darkest moments of history.

Margaret returned to Hamburg, where she found her family struggling to survive in the aftermath of the war. She used her experiences to advocate for peace and understanding, sharing her story with others. Anna became a teacher, dedicating her life to educating future generations about the importance of compassion and empathy.

The legacy of those twelve days in the train car would ripple through their lives and the lives of others, a reminder that even in the depths of despair, humanity can shine through.

Conclusion

The story of the German women POWs is a testament to the resilience of the human spirit and the power of compassion. It challenges us to reflect on our beliefs and prejudices, urging us to see the humanity in others, regardless of the circumstances. In a world often divided by hatred and fear, their journey serves as a beacon of hope, reminding us that kindness can indeed change lives and heal wounds that run deep.