🇺🇸🇺🇸🇺🇸They Laughed at America’s Copy — Then 55,000 Packard Merlins Buried the Luftwaffe

In the winter of 1943, deep within the cold, industrial heart of Recklinghausen, Germany, a group of Luftwaffe engineers gathered around a drafting table cluttered with blueprints. The atmosphere was thick with the scent of oil and tobacco, mingling with a palpable sense of superiority. Among them was Oberingenieur Franz Müller, a man whose confidence in German engineering was as solid as the aircraft they crafted. As he adjusted his wire-rimmed glasses and perused a new intelligence file marked “US Army Air Force Engine Type 1,650,” he couldn’t help but laugh.

“Packard Motor Company,” he scoffed, reading the name aloud. “The Americans have copied the Merlin. They build luxury cars, and now they think they can build a Rolls-Royce.” His colleagues joined in a chorus of laughter, their arrogance echoing off the hangar walls. Outside, the wind howled, but inside, the warmth of self-assurance enveloped them.

For Müller and his peers, engines were sacred. They believed that perfection was not assembled but crafted, each component a testament to human skill and artistry. To them, the Packard name—known for producing automobiles for the wealthy—sounded like a punchline, not a threat. “They cannot even produce enough mechanics to maintain them,” Müller sneered, “and they expect to build 50,000.”

Behind him, his assistant Carl flicked ash from his cigarette. “Mass production kills precision,” he declared, a phrase that resonated in German engineering circles. They recalled the Spitfires they had examined, each Merlin engine singing with subtle imperfections—crafted by skilled hands, not machines. How could a factory in Detroit replicate that?

The Underestimation of American Ingenuity

As they continued to mock the Americans, Müller noted the intelligence report detailing how the United States planned to produce 5,000 Rolls-Royce Merlin engines under license. He tapped the paper with his pencil, writing in the margin, “Copy = inferior by design.” Little did they know that their underestimation of American ingenuity would soon come back to haunt them.

Müller and his colleagues were convinced that the Americans, with their emphasis on mass production, would ruin the intricate design of the Merlin. “They will copy the form, not the function,” Müller muttered. Outside, the roar of a DB 6005 engine filled the air, a sound that every German pilot trusted more than his own heartbeat. “That’s how an engine should sound—handbuilt, alive, pure,” Müller said, closing the American file with a snap.

What Müller couldn’t fathom was that across the Atlantic, in a massive brick factory beside the Detroit River, those so-called toys were already running smoothly, endlessly, and identically. He couldn’t imagine an engine that didn’t need a craftsman to make it sing. In Germany, perfection was art; in America, it was arithmetic.

That night, Müller recorded his thoughts in his logbook. “American arrogance continues,” he wrote. “They believe machines can replace men. They believe quantity can replace quality. They may have factories, but we have engineers.” He underlined the last sentence twice. Years later, historians would find that notebook, and the irony would not be lost on them.

The Shift in Production Philosophy

Meanwhile, in Derby, England, the Rolls-Royce factory hummed with activity. The Merlin engine, a symbol of British defiance, was being born one breath, one heartbeat at a time. Craftsmen like Harold Watkins worked meticulously, his fingers moving with the precision of a surgeon. Each engine consumed over a thousand man-hours of labor, and every component bore its own quirks and secrets. Rolls-Royce engineers tuned these imperfections like violin makers adjusting strings by ear.

When the first Spitfire took flight with a Merlin under its cowl, Britain discovered that sound could carry courage. Pilots claimed they could feel the engine breathe with them, responding like a living creature. The Merlin’s growl became the anthem of survival during the Battle of Britain, a metallic heartbeat promising that the island still lived.

But as the war raged on, the demand for engines skyrocketed. British factories struggled to keep pace, working 20-hour days yet barely maintaining output. Each engine was precious; when one failed, a pilot’s life often ended in flames. The stakes were high, and desperation set in.

In a controversial decision, Rolls-Royce handed the Merlin blueprints to Packard Motor Company in Detroit. Many workers felt insulted. “They’ll ruin it,” one machinist exclaimed. “Americans make cars, not engines fit for heaven.” Yet, war has a way of forcing humility, and the Spitfire and Lancaster could not wait for pride.

The American Manufacturing Revolution

As wooden crates filled with blueprints left Derby for Detroit, American engineers faced a monumental challenge. The blueprints arrived, a riddle written in another language—measurements in fractions, tolerances in decimals. Packard’s lead engineer, Jesse Vincent, realized that if they built the Merlin the British way, they would produce only one engine a month. They needed to build one every hour.

The challenge was both technical and philosophical. Rolls-Royce believed in perfection through craftsmanship; Packard believed in perfection through process. So, they redrew every blueprint from scratch, translating artistry into mathematics. They standardized threads, bearings, and fittings so that every part could fit every engine, designing jigs that held components with such precision that human error vanished from the equation.

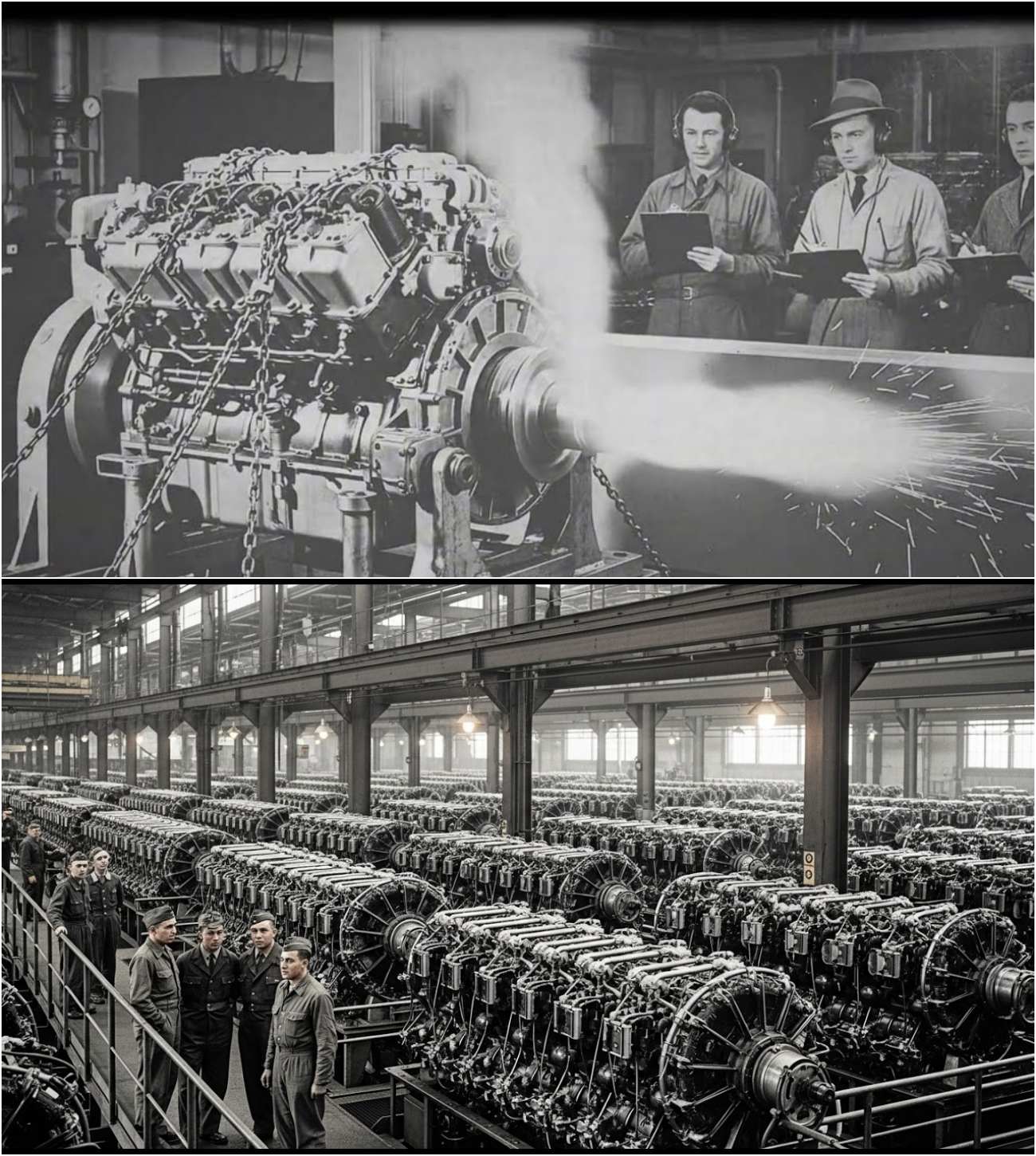

Inside the Packard plant, the factory ran 24 hours a day, its brick walls vibrating with the pulse of war. Women in coveralls worked under the glare of mercury lamps, each specializing in a single operation. The clang of wrenches formed a rhythm, mechanical yet strangely human. Observers described it as watching an orchestra where every instrument was made of steel.

But doubts lingered. British advisers questioned whether mass production could match handcrafted tolerances. One senior Rolls-Royce engineer muttered, “They’ll build fast, yes, but they’ll build wrong.” Vincent, however, was determined. “We’re not just building engines,” he told his team. “We’re building a new kind of perfection, one that anyone anywhere can repeat.”

The Test of Time and Performance

By December 1942, the first prototype, designated V-1650, sat on a dynamometer stand. When the ignition switch turned, the engine roared to life, smooth and steady. The vibration that had plagued early British Merlins was gone. Reporters were invited to witness the first test run, and the data confirmed their hopes: the Packard Merlin delivered the same power with lower fuel consumption and fewer leaks.

Within six months, Packard could build a Merlin every 60 minutes. Each engine cost less, lasted longer, and required fewer mechanics to service. Precision had been democratized. Meanwhile, British factories watched in astonishment as the first American-built Merlins arrived. They fit perfectly into Spitfires and Mosquitoes, bolted on without modification.

The combination of the Packard Merlin and the P-51 Mustang was revolutionary. With its high-altitude supercharger, the Mustang soared to 437 mph, outpacing anything the Germans could send against it. What began as a copy had transformed into a legend.

The Turning of the Tide

As the war progressed, German engineers who once mocked the American license now received intelligence reports indicating that American factories were producing 500 Merlins a week. Müller, the same engineer who had laughed at the blueprints, stared at the figures in disbelief. “They build them like toys,” he whispered.

But these toys were filling the skies over Europe. The Luftwaffe faced an unending supply of American-built engines, and their nightmare was not just the aircraft but the relentless production that kept them flying. Reports piled up on Generalfeldmarschall Erhard Milch’s desk, noting that American industrial capacity was beyond measurable limits. “They have turned engineering into warfare,” he lamented.

In Detroit, the factory lights never dimmed. Welders worked under the rhythmic glare of sparks, and inspectors checked gauges against master templates. Every six minutes, a new engine rolled off the line, each one identical, each one ready for flight. The transformation was complete: the same American industry that once built luxury cars now built precision for survival.

A Lesson in Humility and Adaptability

As the war drew to a close, the statistics were brutal. Packard had produced 55,000 Merlin engines, while Rolls-Royce had built only 20,000 since 1939. The Germans, once proud of their craftsmanship, found themselves outpaced by a philosophy that worshipped replication over artistry. Müller, weary from the weight of defeat, reflected on his earlier convictions.

“They have made perfection common,” he noted in his final report. “In their hands, genius became infrastructure.” The Germans had built masterpieces, but the Americans had built a method. By the summer of 1944, the Allies owned the skies, and the sound of the Packard Merlin was the sound of inevitability.

In Munich, nearly two decades later, Müller visited a new aviation exhibit featuring Allied aircraft. When he saw the restored P-51 Mustang, he could hardly believe it. The engine, labeled “Packard Motor Division, Detroit, USA,” roared to life, awakening memories of a past he thought he had buried.

He approached the aircraft, feeling a sense of respect for what it represented. “You were never a copy,” he whispered, acknowledging the evolution of engineering that had taken place. That night, he opened his old logbook, crossing out the line he had once written: “Copy = inferior by design.” Below it, he penned, “A copy made with understanding becomes an invention.”

Conclusion: The Legacy of the Packard Merlin

The story of the Packard Merlin is not just about engines; it’s about resilience, adaptability, and the power of collaboration. It teaches us that greatness does not always reside in individual brilliance but can emerge from a collective effort to innovate and improve. In the end, the true genius of the Packard Merlin lay not in its design alone, but in its ability to be produced at scale, ensuring that the Allies had the upper hand in the skies.

As we reflect on this narrative, we are reminded that the lessons of history are not just about the past; they are about how we approach challenges today. In a world where collaboration and innovation are more important than ever, the legacy of the Packard Merlin continues to inspire us to strive for excellence, not just as individuals, but as a united force capable of achieving the extraordinary.