Mummification is the process of preserving the body after death by deliberately drying or embalming flesh. This typically involved removing moisture from a deceased body and using chemicals or natural preservatives, such as resin, to desiccate the flesh and organs.

Older mummies are believed to have been particularly preserved by burying them in dry desert sands and were not chemically treated. The Egyptians considered that there was no life beyond the present, so wanted to ensure it would continue after death. This led to the mummification process, which came about amidst fears that if the body was destroyed, a person’s spirit might be lost in the afterlife.

The Mummification Process in Ancient Egypt. Illustrated by: Christiaan Jego

Ancient Egyptians loved life and believed in immortality. This motivated them to make elaborate plans for their death. While this may seem contradictory, for Egyptians, it made perfect sense: They believed that life would continue after death and that they would still need their physical bodies. Thus, preserving bodies in as lifelike a way as possible was the goal of mummification, and essential to the concept of life.

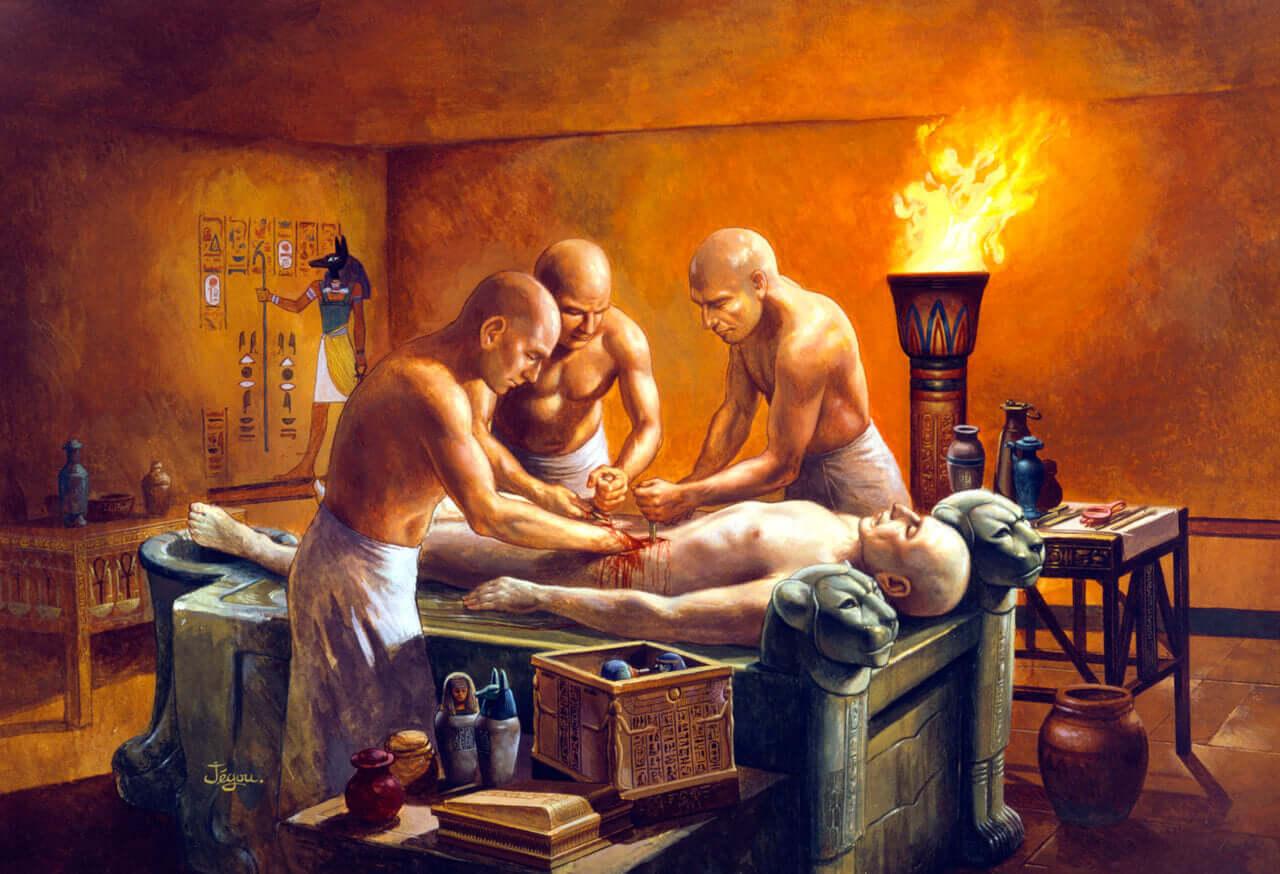

Today, Egyptologists have discovered that there was a complex organizational structure behind embalming. After death, the embalmers would immerse the bodies with balms, and remove the concepts of the torsos (as seen here) and replace them with viscous and aromatic substances.

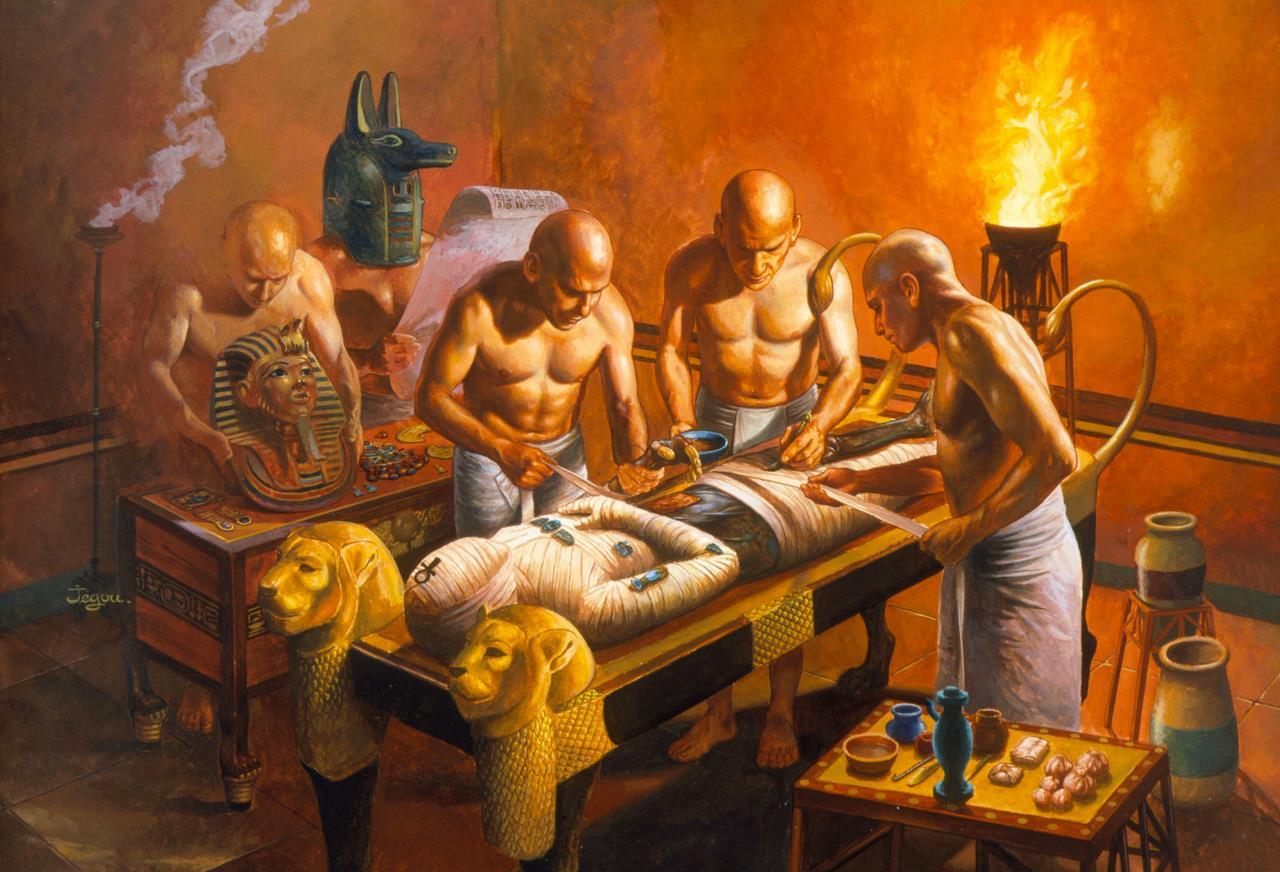

Finally, the body was wrapped in cloths (as seen below). When a king was mummified, a death mask (center left) made of gold and lapiz lazuli was also made and placed on the mummy’s head. The process was done to preserve the body. This kept a person’s life-force (known as Ka) intact according to the ancient Egyptian belief.

“Today, Egyptian practices for death and the afterlife are intimately associated with mummies, which both fascinated and terrified people for centuries. In countless movies, these preserved bodies from ancient times are often shown to be mystical creatures that come back from the dead to exact revenge.

In the same vein, over the centuries, Egyptian societу suggested that there was a tomb curse or “curse of the pharaohs” that ensured anyone who disturbed their tombs, including thieves and archaeologists, would suffer bad luck or even death.

Analysis attests to the mummy of Senedjem, well-preserved from the Tomb of Senedjem (TT1). New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty, ca. 1292-1189 BC. Deir el-Medina, West Thebes.

In reality, Egyptian mummies have been preserved throughout time due to the meticulous process that created them, and while Egyptian mummies are the most famous, there are preserved bodies from all around the world from across history.

Some of these mummies were objects of nature, while others were more intentional, preserving through human intervention. In Egypt, the first mummies seem to have been naturally, but after their discovery, mummification became a time-honored tradition in this ancient civilization.”

The Mummies of Ancient Egypt: The History and Legacy of the Egyptians (#aff)

Mummification process is believed to have taken around 70 days, accompanied by many rituals. The organs of the deceased were carefully removed through a small incision (10 cm) in the left side of the body and preserved in canopic jars.

The body was dried in sodium nitrate, or nitrate salt brought from Wadi El Natrun, for about 40 days, and finally wrapped in bandages of linen. Medicinal amulets were placed within the wrappings to protect the deceased. The family then received the body and placed it in a coffin for burial.

The mummification processes used by the ancient Egyptians are known to us through descriptions left by Herodotus (5th century BC) in Book II of his Histories.

The longest and most costly procedure required removal of the internal organs from the body with the liver, lungs, intestines, and stomach being embalmed separately. The brain was extracted with a hook inserted through the nasal cavity while the other organs were removed through a cut made in the lower part of the abdomen.

Next, the body was cleaned and filled with natron, a type of salt, and the cut was sewn up and protected by a plaque.

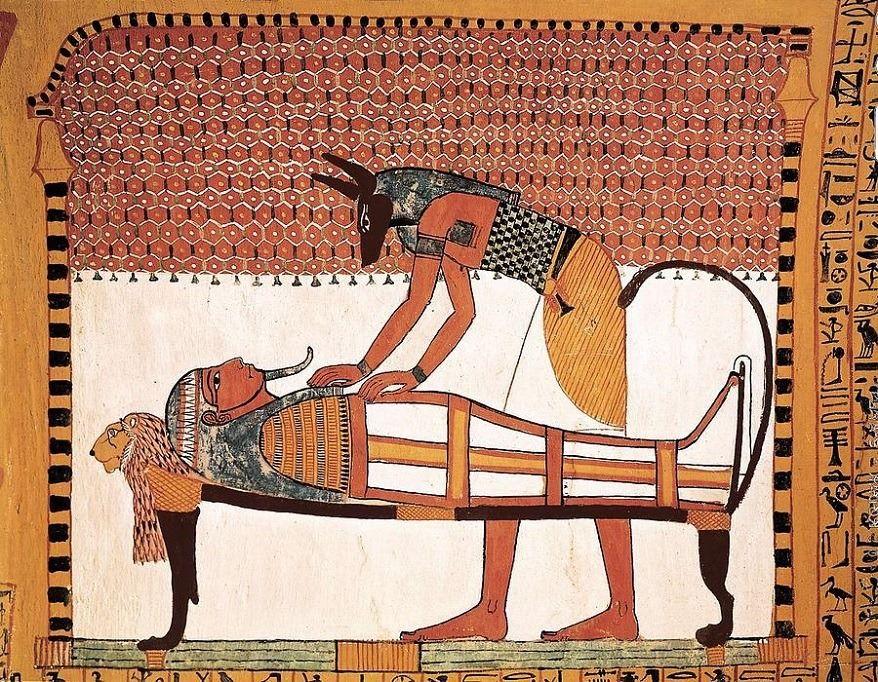

The ancient Egyptians were only able to adapt mummification to dead humans but also to many animals (cats, dogs, birds, snakes, and crocodiles) for votive and ritual purposes. The god Anubis was also known as Inpu (the jackal) was representing the god of death, embalming, and mummification.

Anubis functioned as divine embalmer, and the priests who supervised the mummification process would wear masks of Anubis to stand in for the god. This divine impersonation extended to the funeral, where Anubis (in the form of a disguised priest) would present the mummy for essential ceremonies.

Many of the adult mummies appear in ancient Egypt, however, it was in ancient Egypt, however, that mummification reached its greatest elaboration. The first Egyptian mummies appeared in the archaeological record at approximately 3500 BC.

By the time of the Old Kingdom, or Age of the Pyramids (circa 2686-2181 BC), mummification was well entrenched in Egyptian society. It became a mainstream cultural practice, reaching particular heights of sophistication during the New Kingdom (circa 1550-1070 BC).

The mummification in ancient Egypt was typically reserved for the elite of society such as royalty, noble families, government officials, and the wealthy. Common people were rarely mummified because the process was expensive. The ancient Egyptians believed that mummification would guarantee that the soul of the buried person would endure.

In ancient Egypt, gold held significant symbolism in the process of mummification. Gold was associated with the Sun God Ra, who was believed to have the power to grant eternal life. It represented the divine and was considered a symbol of immortality and the afterlife.

Gold was used to adorn the bodies of the deceased, particularly kings and other high-ranking individuals, as it was believed to protect and preserve their bodies in the journey to the afterlife. It was also used to create intricate burial masks and other funeral objects, showcasing the wealth and status of the deceased.

In ancient Egypt, gold was used to adorn the bodies of the deceased, particularly kings and other high-ranking individuals, as it was believed to protect and preserve their bodies in the journey to the afterlife. It was also used to create intricate burial masks and other funeral objects, showcasing the wealth and status of the deceased.