Valley of the Kings: where Egypt’s most powerful pharaohs hid their enormous wealth

Source: https://pixabay.com/photos/egypt-valley-kings-temple-desert-493/

Source: https://pixabay.com/photos/egypt-valley-kings-temple-desert-493/

The Valley of the Kings, a UNESCO World Heritage site, is a captivating and historically significant necropolis located on the west bank of the Nile River, near the modern-day city of Luxor in Egypt.

Steeped in mystery and intrigue, the valley served as the royal burial ground for pharaohs, their families, and other high-ranking officials during the New Kingdom period (circa 1539–1075 BCE), primarily across the 18th, 19th, and 20th dynasties.

Carved into the rocky hills, this ancient burial site was chosen for its remote location and natural geological features that provided both protection and symbolism.

The Valley of the Kings is home to 63 numbered tombs, each varying in size, design, and complexity. The tombs are adorned with stunning artwork, carvings, and inscriptions that offer insight into the lives, beliefs, and funerary practices of ancient Egyptians.

Its secretive location

The Valley of the Kings is situated on the west bank of the Nile River, approximately 500 miles south of Cairo and close to the modern city of Luxor, which was once known as Thebes, the capital of ancient Egypt during the New Kingdom period.

The valley’s location, surrounded by the Theban Hills, provided a secluded and well-protected area for the construction of the royal tombs.

The valley is divided into two sections: the East Valley and the West Valley. The East Valley is the more extensively studied and visited area, as it contains the majority of the known tombs.

The West Valley, on the other hand, is less explored and has fewer tombs, though it is home to the Tomb of Ay (KV23) and the enigmatic Tomb of Amenhotep III (WV22).

The landscape of the Valley of the Kings is characterized by its barren, rocky terrain and the natural pyramid-shaped peak of Al-Qurn, which dominates the skyline.

The ancient Egyptians believed that this peak was a symbol of the sacred mound of creation, and its presence may have influenced the choice of this location as a burial site.

The valley’s remote location and natural barriers offered protection from tomb robbers and the harsh elements, while its proximity to the Nile River enabled the transport of materials and resources necessary for tomb construction.

Google Maps content is not displayed due to your current cookie settings. Click on the cookie policy (functional) to agree to the Google Maps cookie policy and view the content. You can find out more about this in the Google Maps privacy policy.

When were the tombs built?

The Valley of the Kings holds immense historical significance as the primary burial site for the pharaohs and other prominent figures of the New Kingdom period in ancient Egypt, which spanned from around 1539 to 1075 BCE.

This era is considered the zenith of ancient Egyptian power and prosperity, encompassing the 18th, 19th, and 20th dynasties.

Prior to the New Kingdom, pharaohs were typically buried in pyramid structures, such as those seen at Giza.

However, due to the vulnerability of pyramids to tomb robbers and the desire for greater privacy and security, the decision was made to create hidden tombs in the Valley of the Kings.

This shift in burial practices marked a significant change in ancient Egyptian culture and demonstrated the evolving beliefs surrounding the afterlife.

The tombs in the Valley of the Kings not only served as the final resting place for the deceased but also functioned as repositories for the treasures and artifacts that the pharaohs believed would be necessary for their journey into the afterlife.

The incredible tomb designs

The tombs in the Valley of the Kings showcase the architectural ingenuity and artistic mastery of ancient Egyptian builders and craftsmen.

While tomb designs evolved over time, incorporating additional elements and varying in complexity, certain key features remained consistent across different dynasties.

A typical tomb layout consists of a descending corridor, which leads to the burial chamber(s) and side chambers.

The burial chamber itself was the central and most sacred part of the tomb, housing the sarcophagus of the deceased and often featuring a vaulted or flat ceiling.

Additional side chambers, also known as annexes or storerooms, would be used to store funerary goods, offerings, and other artifacts for the afterlife.

The tomb architecture in the Valley of the Kings also reflects a functional purpose. The underground design was intended to maintain a stable environment and protect the tomb’s contents from extreme temperature fluctuations, humidity, and other environmental factors.

As tomb construction progressed through the New Kingdom, the designs became more elaborate and complex, with some tombs featuring multiple levels, pillared halls, and additional chambers.

Notably, the tombs of the 19th and 20th dynasties often included a J-shaped design, with the burial chamber located at the farthest point from the entrance.

How the tombs were decorated

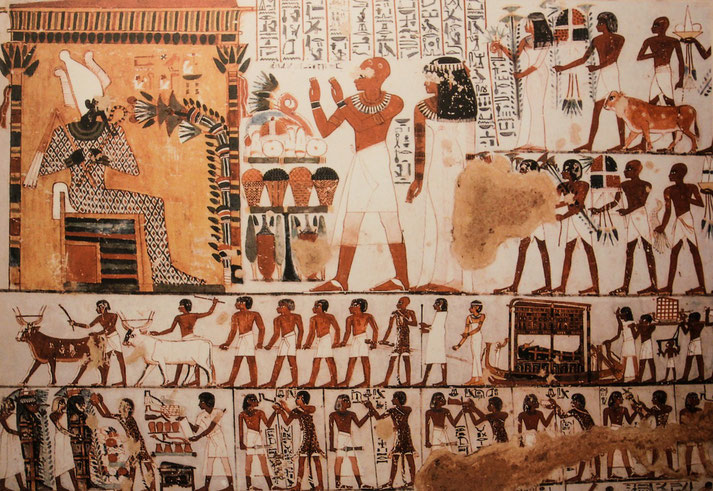

The tombs in the Valley of the Kings are renowned for their stunning decorations and inscriptions, which played a crucial role in the beliefs and rituals associated with the afterlife in ancient Egypt.

These artworks and texts provide invaluable insights into the religious practices, cultural values, and daily lives of the New Kingdom Egyptians.

Wall paintings and carvings: The tomb walls were often adorned with elaborate paintings and carvings that depicted scenes from the life of the deceased, religious rituals, and mythological stories.

These vibrant images were created using mineral-based pigments, and the artists employed a range of techniques to capture the intricate details of the scenes.

The paintings and carvings were intended to celebrate the life and accomplishments of the deceased, as well as to ensure their successful transition to the afterlife.

Source: https://pixabay.com/photos/mural-egypt-pharaoh-luxor-tomb-484706/

Source: https://pixabay.com/photos/mural-egypt-pharaoh-luxor-tomb-484706/

Funerary texts: Many tombs featured a variety of religious and funerary texts inscribed on the walls, intended to guide and protect the deceased on their journey through the afterlife. Some important examples of these texts include:

The Amduat

Also known as the “Book of What is in the Underworld,” the Amduat chronicles the sun god Ra’s nightly journey through the twelve hours of the night, which was symbolically linked to the journey of the deceased pharaoh.

The Book of Gates

This funerary text describes the passage of the sun god Ra through the twelve gates of the underworld, each representing an hour of the night, and the challenges and obstacles he encounters.

The Litany of Re

A series of prayers and incantations addressed to the sun god Ra, intended to protect and rejuvenate the deceased in the afterlife.

Protective spells and symbols

In addition to the paintings and inscriptions, tombs often featured various protective spells and symbols, such as the “djed” (representing stability) and the “tyet” (associated with the goddess Isis and protection). These symbols were believed to empower the deceased and safeguard them from potential dangers in the afterlife.

The most famous discoveries

The Valley of the Kings is home to numerous tombs with unique features, historical significance, and intriguing discoveries. Some of the most notable tombs include:

Tutankhamun’s Tomb (KV62)

Discovered by British archaeologist Howard Carter in 1922, the tomb of the young pharaoh Tutankhamun is arguably the most famous in the Valley of the Kings. Its significance lies in the fact that it was found largely intact, with over 5,000 artifacts, including the iconic golden death mask, providing invaluable insights into the funerary customs and material culture of the 18th dynasty.

Tomb of the sons of Ramesses II (KV5)

This tomb is the largest in the Valley of the Kings, with over 120 chambers. It was initially discovered in 1825 by James Burton, but its true extent and significance were only revealed during excavations led by Kent Weeks in the 1990s. The tomb was built for the sons of Ramesses II, one of Egypt’s most powerful and long-reigning pharaohs.

Tomb of Seti I (KV17)

Also known as the Belzoni Tomb, after its discoverer Giovanni Battista Belzoni, the tomb of Seti I is the longest and deepest in the valley. It is renowned for its exceptional artwork, including some of the finest bas-reliefs and paintings from the New Kingdom. The tomb features a unique astronomical ceiling with detailed depictions of constellations and celestial figures.

Tomb of Thutmose III (KV34)

Discovered by Victor Loret in 1898, the tomb of Thutmose III is notable for its unusual shape, with a steep, narrow entrance corridor leading to a large, oval-shaped burial chamber. The tomb’s well-preserved wall paintings feature a range of religious texts, including the Amduat and the Litany of Re, as well as a unique depiction of the pharaoh being embraced by the sky goddess Nut.

Source: https://pixabay.com/photos/tomb-egypt-ancient-brown-tomb-4300251/

Source: https://pixabay.com/photos/tomb-egypt-ancient-brown-tomb-4300251/

Who excavated the tombs?

The Valley of the Kings has been the focus of archaeological interest for centuries, with numerous excavations and discoveries made by various key figures in the field of Egyptology.

Some of these influential archaeologists and explorers include:

Giovanni Battista Belzoni (1778-1823)

An Italian explorer and archaeologist, Belzoni made significant contributions to the study of the Valley of the Kings, including the discovery of the tomb of Seti I (KV17) in 1817. His work helped lay the foundation for future archaeological excavations in the valley.

Jean-François Champollion (1790-1832)

A French scholar and the decipherer of the Rosetta Stone, Champollion visited the Valley of the Kings in 1828-1829 as part of a larger expedition to Egypt. His work in the valley focused on the study of tomb inscriptions, which he used to further develop his groundbreaking understanding of the ancient Egyptian language and writing systems.

Howard Carter (1874-1939)

A British archaeologist, Carter is best known for his discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun (KV62) in 1922, which remains one of the most significant archaeological finds in history. Carter’s meticulous excavation and documentation of the tomb’s contents have greatly contributed to our understanding of ancient Egyptian funerary practices and material culture.

Kent Weeks (born 1941)

An American Egyptologist, Weeks has conducted extensive research in the Valley of the Kings, particularly focusing on the tomb of the sons of Ramesses II (KV5). His work in the 1990s revealed the true extent and complexity of KV5, which was previously believed to be a small, insignificant tomb.

Otto Schaden (1937-2015)

Schaden was an American Egyptologist who led the excavation of the tomb KV63, the first tomb discovered in the Valley of the Kings since Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922. Although not a royal tomb, KV63 has provided important information about tomb construction and funerary practices during the 18th dynasty.

The Valley of the Kings today

The tombs, with their intricate designs, exquisite artwork, and storied history, serve as a testament to the extraordinary achievements and cultural heritage of ancient Egypt.

The preservation and conservation of the tombs in the Valley of the Kings is of utmost importance to ensure the long-term protection of these invaluable archaeological sites and the irreplaceable cultural heritage they represent.

The ongoing efforts to preserve and conserve these sacred spaces ensure that future generations can continue to marvel at the wonders of the Valley of the Kings and draw inspiration from the legacy left behind by the pharaohs.