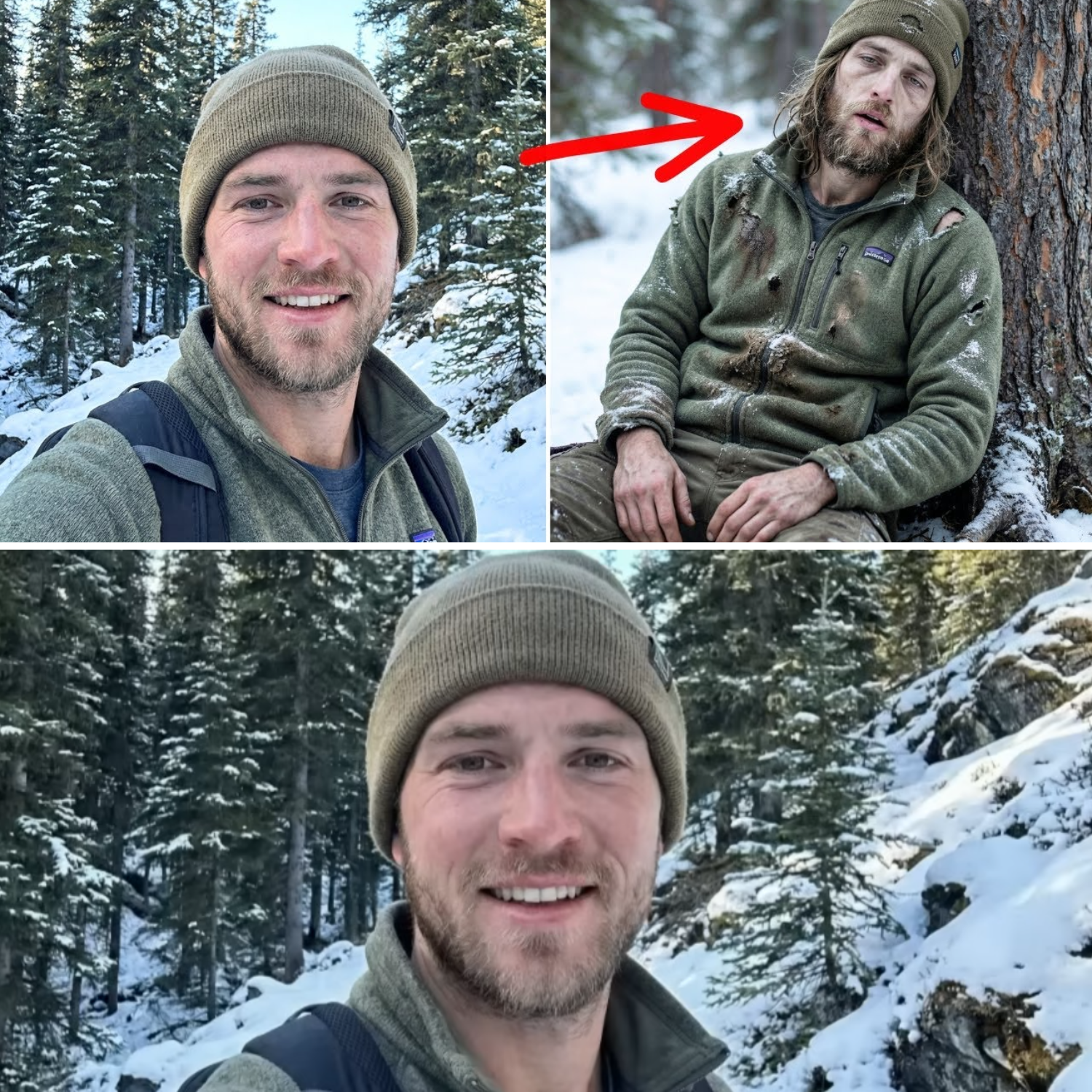

Alaska’s Frozen Nightmare: Hiker Vanished—Found After a Year, Half-Dead and Haunted by the Wild That Tried to Kill Him

In late August 2004, Paul Warren walked into the Alaskan wilderness near Denali National Park, carrying nothing but a backpack, camera gear, and the kind of quiet desperation that only heartbreak can bring. At 32, Paul was a wilderness photographer whose images captured the soul of places untouched by humans. But this trip was different. He was running—not toward beauty, but away from the ruins of his life: a broken engagement, a fractured relationship with his family, and a gnawing emptiness that no gallery show or mountain sunrise could fill.

He filed his permits, told the park service he’d stick to marked trails, and promised his brother Dennis he’d be careful. But Paul had no intention of following the rules. He wanted to disappear into the wild, to find a valley no one had ever photographed, to prove—to himself, to Bethany, to the world—that he could survive alone with nothing but his skill and his sorrow.

For three days, Paul lived the dream. He followed trails, shot rolls of film, slept beneath the stars, and let the silence of Alaska wrap around him. But on the fourth day, he saw what he was looking for: a pristine valley, untouched, calling to him like a siren. He left the trail, promising himself he’d be careful, that he’d return before nightfall. He didn’t.

The valley was everything he’d hoped—wild grasses, an alpine lake, mountains reflected in water so clear it seemed unreal. Paul photographed everything, losing himself in the work. But as the sun dipped behind the peaks, he realized he had no idea how to get back. The forest was a maze, the trees identical, the ground unforgiving. He tried to retrace his steps, but every direction looked the same. His compass was useless without landmarks. He was lost.

Night fell quickly. The temperature dropped below freezing, and Paul’s confidence shattered. The wilderness was indifferent to his skill, his gear, his need for meaning. He made camp under a spruce tree, rationed his food, and told himself he’d find the trail in the morning. But morning brought only frost, hunger, and the realization that he was alone, truly alone, in a world that did not care if he lived or died.

Days blurred into weeks. Paul rationed his food, foraged for berries and roots, melted snow for water. His body began to shrink; his face hollowed, his muscles wasted. He tried to follow streams, hoping they would lead to civilization, but every river twisted deeper into the wild. Then came the storm—a blizzard that tore his tent away, scattered his supplies, and left him with nothing but a sleeping bag, a few tools, and his camera gear.

He found a cave beneath a granite shelf and huddled there as the storm raged for days. When it broke, the world was buried in snow. His tent was gone. His stove was gone. Half his clothes were missing, lost to the wind. He was left with scraps and memories.

Winter in Alaska is not a season—it’s an executioner. The sun disappeared, leaving Paul in near-constant darkness. Temperatures plunged to forty below zero. Frostbite claimed his toes, turning them black and dead. His body consumed itself, burning muscle and fat until he was little more than bones wrapped in skin. He set snares for rabbits, climbed trees for pine nuts, stripped bark for bitter tea. Every day was a fight for calories, for warmth, for sanity.

The loneliness became a physical pain. Paul talked to himself, sang songs, recited poems, argued with ghosts. Bethany visited him in hallucinations, her voice gentle and forgiving. Dennis appeared, lecturing him on survival, pointing out every mistake. The line between reality and delusion blurred until Paul no longer cared which was which.

Spring brought no relief. His body was too damaged, his mind too fractured. The frostbite spread. Infection set in. His camera bag was lost to the river, swept away in a desperate attempt to find a way out. The photographs he’d risked everything for were gone, swallowed by glacial water. Paul wept for his lost art, his lost identity, his lost hope.

But something kept him alive—a stubborn refusal to let the wilderness win, or maybe just the biological imperative to survive. He found an old trap, rusted and broken, proof that humans had survived here before. He carried it back to his cave, a talisman against despair.

Summer returned, but Paul could no longer recover. His digestive system was ruined by starvation. Every cut became an infection. His body failed, his mind drifted. He wandered the forest, barely able to walk, his clothes hanging from his skeletal frame. On an August afternoon, he collapsed against a spruce tree, ready to die.

That’s where the rangers found him. Jason Owens and Steve Tharp were on a routine patrol when they saw the figure slumped against the tree, so thin and weathered he looked like a corpse. But Paul’s eyes moved. He was alive—barely. The rangers called for a helicopter, kept him conscious, and prayed he would survive the flight to Anchorage.

Paul arrived at the hospital more dead than alive. He weighed 93 pounds. His core temperature was 89 degrees. His kidneys and liver were failing. Five toes and part of his heel were amputated to save his life. His family flew in, stunned by the impossible return of a man they’d buried in an empty casket months before.

Recovery was slow and agonizing. Paul learned to walk again, to eat, to live with the scars on his body and the fractures in his mind. Nightmares haunted him—of bears, of endless forests, of Bethany’s voice. He developed severe PTSD, panic attacks, a fear of enclosed spaces. But he survived.

He picked up a camera again, tentatively, unsure if the photographer he’d been had died in Alaska. He started photographing ordinary things—light on a kitchen table, rain on a windowpane, his nephew’s hands. The images were simple, but they proved he could still create.

Paul’s story became an exhibition—365 Days—a memoir of survival, trauma, and the brutal beauty of the wilderness. It resonated with people who had never set foot in Alaska but knew what it meant to be lost. The exhibition traveled the country. Paul spoke at seminars, trauma groups, sharing not advice, but presence.

Three years after his rescue, Paul returned to Alaska with Jason Owens. He stood on the ridge overlooking the valley that had nearly killed him, understanding finally that the wilderness was not his enemy or his friend. It was simply the land—indifferent, beautiful, and deadly.

Paul Warren survived a year alone in Alaska, stripped of everything but the will to live. His story is not just about endurance, but about transformation, about the price of seeking meaning in places that do not care if you survive. If this story froze your blood, share it. The wild is not just a place—it’s a crucible, and sometimes, the only way out is to become someone new.