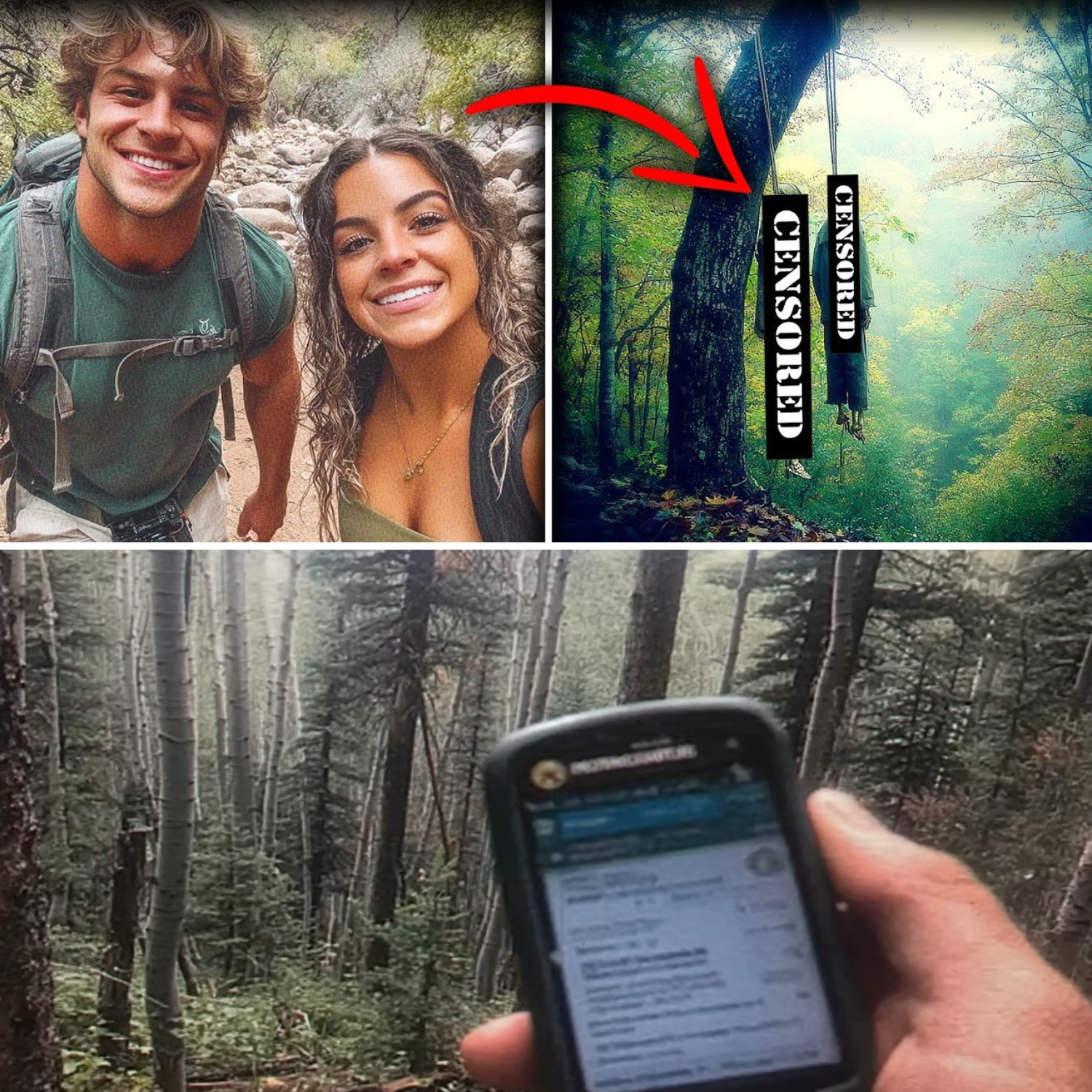

“Boy and Girl Vanished in Colorado — 5 Years Later, Their Bodies Were Found Hanging from a Tree”

In June of 2014, 22-year-old photographer Aldrich Wayne and his girlfriend, 23-year-old geology student Ara Marorrow, set out on a hiking trail in the San Isabel National Forest in Colorado. Their goal was to reach a picturesque plateau with unique rock formations. They never returned. For five long years, they were considered missing until, in May of 2019, geologist Eliza Reynolds came across a gruesome discovery in a remote tract known as the Stone Claw.

High on the branch of an old spruce tree hung two dark silhouettes, almost black with time. The forest wilderness had been their last secret hideout for five years. But now, the most terrible question remained unanswered: who and why had turned the dream of perfect landscape photographs into a horrific end to two young lives?

They started their hike at 7 a.m. on June 15, 2014. Dawn had just touched the tops of the spruce trees, but there were still islands of fog in the crevices of the San Isabel National Forest. Aldrich Wayne was carefully checking his gear while his girlfriend, Ara Marorrow, made the last entries in her journal. Their blue Jeep Cherokee was parked at the Mountain Duth trailhead, one of the least visited trails in this part of Colorado.

“We’ll be back Sunday night, no later than 8,” Ara told her mother over the phone at 10:45 from the Rocky Mountain gas station in Weserve. It was their last contact with the outside world. Aldrich slung his heavy backpack over his shoulders. The 22-year-old naturalist photographer dreamed of taking a series of pictures of rare rock formations on the plateau at the moment when the evening sun turned them coppery. These photographs were to be the centerpiece of his first solo exhibition scheduled for July.

Ara, a year older than him, took her geological hammer. She was studying the local rocks for her graduate thesis and planned to collect samples from the upper tier of the plateau where most tourists did not reach. “It’s going to be hot today,” Aldrich said, taking off his denim jacket and throwing it in the back seat. This simple gesture would later become the first proof that they had actually set out on the trail.

The first mile was easy; a wide path stretched between pine trees. According to the GPS, there were about eight miles left to the coveted plateau, which was becoming increasingly difficult. They expected to get there by evening, spend the night, and return the next day. It was a simple plan that thousands of hikers followed every year without any problems.

At the first halt near a small stream, Ara took a picture of an unusual rock with her phone. This photo would remain in her cloud storage as the last moment of a peaceful trip. “Do you hear that?” Aldrich suddenly asked, raising his head as if he had heard the sound of an engine. “There are no roads here,” Ara was surprised, but she listened.

“Maybe foresters,” she suggested. They continued on their way, going deeper into the forest where the path became less and less visible. At 1:20 p.m., Aldrich made the last entry in his GPS tracker. They were four miles from the trailhead, near a rocky outcrop where the trail turned sharply east. After that point, their route became a mystery that haunted rescuers, investigators, and relatives for five years.

On Sunday evening, when the young couple did not call or return, their parents began to worry. Ara’s mother dialed her number every 30 minutes, but the phone was unavailable. At 10:30 p.m., Aldrich’s father called the rescue service. “They are experienced tourists,” he explained. “My son is never late. Something has happened.” However, the official search did not begin until 8:00 a.m. on Monday, June 16th.

A team of six U.S. Forest Service rangers and four volunteers from the Colorado Rescue Squad arrived at the trailhead. Their Jeep Cherokee was parked in the same spot where the young couple had left it three days earlier. It was locked, with no signs of forced entry. On the back seat was Aldrich’s denim jacket. There were documents in the glove compartment and a spare water canister in the trunk.

The rescue team split into three parts and began combing the area. Two search dogs, a black Labrador named Rex and a German Shepherd named Sira, picked up the trail of the car but lost it about a mile later in a rocky area. This was exactly where the last entry in Aldrich’s GPS tracker was. By the evening, the entire known part of the route had been examined. No trace of the camp, no scraps of clothing, or signs of struggle. The pair seemed to have vanished into thin air.

The next day, a helicopter joined the search. It circled over the dense forest for five hours, but the pilot, Captain Jeffrey Thompson, reported that the dense tree canopy made it impossible to effectively survey the area from the air. “Sergeant Robert Hayes, the head of the search operation, stood by a map on the hood and circled the areas that had already been checked with a marker. “You see, Mr. Wayne,” he said to Aldrich’s father, who was demanding that the search be expanded. “The San Isabel National Forest is almost 400,000 acres of wilderness. We can’t search it all.”

By the end of the week, the search team had grown to 30 people. It was joined by volunteers from neighboring counties, friends, and colleagues of the missing. They expanded the search area by five miles in all directions from the last known point. On the ninth day, the rescuers found an old tourist campsite two miles from where the dogs had lost their trail. There were traces of a campfire, but experts determined that the fire was at least two weeks old.

On the tenth day, a severe thunderstorm forced the search to stop. When the rain stopped, a new team set out to search, this time with experienced climbers who examined the rocky parts of the route where a fall could have occurred. But even this attempt was in vain. Three weeks after the disappearance, the active phase of the search was officially over. Sergeant Hayes held the last briefing for the media and relatives. “We’ve done everything we can,” he said, visibly exhausted. “It remains to classify this case as a disappearance under unexplained circumstances.”

It was at this point that Aldrich’s father, William Wayne, stood up and said a phrase that would later appear in all the local newspapers. “The forest couldn’t just swallow two people. Someone knows what happened, and I will find that person.” Little did he realize that the answer would come only five years later, and it would be far more terrifying than all his worst guesses.

The San Isabel National Forest, hugging the ridges of the Rocky Mountains, has long been a place where people have gotten lost. But each time there was an explanation—a fatal fall, an encounter with a bear, a sudden change in weather. Disappearance without a trace is a rarity that evokes a strange sense of unease, as if something is fundamentally broken in the usual order of things.

The case of Aldrich Wayne and Ara Marorrow went from active to cold slowly, almost imperceptibly, as the evening twilight enveloped the forest. On July 1st, 2014, the Fremont County Sheriff’s Investigations Department officially reclassified the case from missing persons to missing under unexplained circumstances. “We’re not stopping the search,” Sheriff Michael Caldwell explained at a press conference at 10:00 a.m. “But we need to recognize that all standard procedures have been exhausted.” For the families of the disappeared, this statement was like a funeral bell. But it was not the end of their struggle.

“I can’t just sit here and wait for my child to be found in a ravine 10 years from now,” said Karen Marorrow, Ara’s mother, clutching her daughter’s photo during a meeting with journalists on July 25th. On the same day, Aldrich and Ara’s parents hired a Denver-based private investigator, Michael Thornton, a former Colorado police investigator with 20 years of experience. Thornton specialized in complex disappearance cases in mountainous terrain and had a reputation for not giving up until he’d checked out the last lead.

“The first thing to understand about disappearances in the mountains,” Thornton said during his first meeting with the families on August 5th at 9:30 a.m., “is that they are rarely completely without a trace. Even if a person dies in the most remote corner, there’s always something left behind—a piece of clothing, a footprint, a gas station camera that captured a stranger. We have to find that clue.”

Thornton started the investigation from scratch. He re-interviewed everyone who could theoretically have seen the pair—employees of the Skeleaz gas station, tourists who visited the area in mid-June, rangers, and local residents. The detective spent 14 hours a day reviewing surveillance footage and analyzing mobile traffic in the area. The breakthrough came in October when Thornton was talking to a local forester who happened to mention that illegal loggers periodically appeared in the area.

“Most of them are petty thieves who cut down a few valuable trees,” the forester explained during a conversation near a lookout at an elevation of 9,400 ft. “They can cut down hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of trees in a few days.” A check of the archives revealed that a week before the couple disappeared, rangers had discovered evidence of illegal logging about three miles from the Mountain Duth trail. The trees bore distinctive markings, and satellite imagery showed areas of sparse forest that had recently appeared.

Thornton found that a team of illegal loggers had probably been working in the forest in June 2014. But after the couple disappeared, they vanished without a trace. No informant was able or willing to point them out. The connection is obvious, Thornton wrote in his report to the families on November 1st. Aldrich and Ara could have accidentally stumbled upon an illegal logging site. And if the loggers thought the tourists could inform the authorities, this version provided a logical explanation but had no direct evidence.

Months passed. The families organized a volunteer search on the last Saturday of every month. Friends, colleagues, and ordinary people who cared would gather at the entrance to the Mountain Duth trail and comb through more and more areas of the forest. “We’ll find them,” Aldrich’s father, William Wayne, repeated every time journalists asked if it was time to come to terms with the loss.

On the first anniversary of the disappearance, June 15th, 2015, a memorial plaque was installed at the trailhead. It was engraved with the silhouettes of Aldrich with a camera and Ara with a geological hammer. The inscription read, “Disappeared in the forest, but not in our hearts.” The case gradually disappeared from the front pages of newspapers. New tragedies filled the news, but the families did not stop searching. “If we knew for sure that they were dead, we could bury them and get on with our lives,” said Ara’s mother in a rare interview on the second anniversary of the disappearance. “But living in the dark is unbearable.”

Under Colorado law, a missing person can be declared dead after five years. The families refused to even think about this possibility. By the third anniversary of the disappearance in June 2017, private investigator Thornton had exhausted almost every possible line of inquiry. “I’ve checked out hundreds of theories,” he admitted during a meeting with the families at a Denver coffee shop. “From bear attack to alien abduction. Most of them don’t stand up to fact-checking.”

But one detail kept bothering the detective. Two tourists who visited San Isabel the year before Aldrich and Ara disappeared had similar records. Both mentioned a strange hermit who aggressively demanded they leave his territory. The tourists described him as a tall man with a gray beard dressed in camouflage. One of them clearly remembered that the locals called the man Gordy. The fourth anniversary passed in silent mourning. William Wayne fell ill and was unable to attend the annual memorial ceremony. The number of volunteers in the search was reduced to a handful of his most loyal friends.

It seemed that even nature had forgotten about the tragedy. Young undergrowth had grown where the tents of the search teams once stood. But the forest did not forget. It was just waiting for the time to reveal its secret. In early May of 2019, Colorado Minerals signed a contract with the state government to conduct geological exploration in the San Isabel National Forest. The goal was to create a new geologic map of the region, marking potential mineral extraction sites. For this task, several field geologists were hired to work in different parts of the forest. One of them was 36-year-old Eliza Reynolds, an experienced geologist with a reputation for working in the most difficult conditions.

The five-year silence of the San Isabel forest was about to turn into the loudest scream. Eliza Reynolds had been working for Colorado Minerals for seven years. She joined the company right after graduating from the University of Denver with a master’s degree and had traveled to the most remote corners of the state. But even for her, the task of exploring the Stone Claw tract seemed unusual. Twelve miles from the nearest road, her supervisor, Richard Gardner, warned her when he handed her the map on May 17th at 9:00 a.m. “Can you make it?”

Eliza just smiled. She grew up in a family of climbers and believed that the real work of a geologist begins where all roads end. The next day at 6:00 in the morning, she was already walking along a forest path, carrying a backpack with navigation equipment, tools, and a field diary. The Stone Claw tract lived up to its name; a black basalt outcrop resembled a huge claw stretching into the sky. Around it was a hollow overgrown with a dense spruce forest. It was here, according to the company, that deposits of rare metals could be found.

Eliza worked methodically. She took soil samples, recorded coordinates, and took pictures of rock outcrops—the usual routine of a field geologist. By noon, she had surveyed the eastern part of the hollow and was now moving toward the western slope. At 2:45 p.m., having completed the collection of the last series of samples, she straightened up and stretched, needing her back. At that moment, the clouds parted, and a bright ray of sunlight illuminated the hollow.

Something metallic glinted between the rocks a few dozen feet away. “At first, I thought it was just trash,” Eliza later said. “Tourists often leave cans or foil, but something about that shine was unnatural.” She came closer and saw that between two large boulders was a climbing carabiner with a piece of blue nylon tape attached to it. “These are used to mark routes in difficult terrain.” The color was too bright for something that could have been here for years, Eliza recalled, and the carabiner was deliberately fixed, as if someone was marking the spot.

The experienced geologist immediately sensed that something was wrong. The Stone Claw was not a tourist route. The nearest trail was a few miles away, and few people dared to deviate from it for that distance. Eliza walked over to the boulder and picked up the carabiner. It was well secured and obviously set up deliberately. She looked around, trying to figure out what exactly the mark meant. Climbing the nearest hill to get a better view of the area, she saw it.

In the thick of the spruce forest, about 100 yards away, something dark and motionless was hanging from the branch of a huge tree. Eliza’s heart beat faster. She pulled out the binoculars she always brought with her to look at remote geological formations. What she saw made her shudder. Hanging from a branch of an old spruce, about 20 feet off the ground, were two human bodies. They were almost black with age, and their clothes were tattered by the winds and rains. But even at this distance, Eliza could see a detail that made her cold. One of the figures was wearing a light pink fleece jacket.

“I remembered the news from five years ago,” Eliza later said. “A couple of tourists went missing. The girl was wearing a pink sweatshirt. I thought at the time, what an impractical thing to wear while hiking in the mountains.” Shaking with shock, Eliza checked the coordinates on her GPS receiver. She was at an altitude of 8,682 feet above sea level, at a point with coordinates that would later become crucial in the criminal case.

The geologist did not approach the eerie discovery. As a person working in the field, she knew the rules: do not touch anything that could be evidence and immediately notify the authorities. Looking at the phone screen, Eliza realized that there was no connection. The closest point where she could make a call was at least three miles away at the top of a ridge. She marked the location on her GPS, took a few photos from afar, and quickly gathered her equipment. It was 3:20 p.m., and she had to hurry to reach the communication point before dark.

The climb up the ridge took almost two hours. When Eliza finally saw two bars of signal on her phone screen, it was already 5:10 p.m. She dialed the emergency number. “Service 911, what is your emergency?” a calm female voice answered.

“My name is Eliza Reynolds. I’m a geologist with Colorado Minerals.” Her voice trembled despite her best efforts to speak clearly. “I found bodies. Two people. They’re hanging from a tree. I think they are the hikers who disappeared five years ago.”

The operator asked her to stay put and told her that she was sending a search and rescue helicopter to the area. As she waited, Eliza sat on a rock, looking at the sun sinking toward the horizon, and felt the cold chill seep into her bones. Despite the warm May evening, the helicopter appeared 40 minutes later. Two officers from the Fremont County Sheriff’s Office and a National Forest Ranger descended from it. They quickly interviewed Eliza and, having received the coordinates, went to the location.

“I’m going to stay here,” she said when the ranger asked her to join him. She was still shaking. The officers returned 40 minutes later. Their faces were stern. “It looks like you’re right,” said Sergeant Michael Baker, the senior officer. “It looks like those missing hikers, but we need to wait for experts to confirm.”

Already in the helicopter that was taking her to the nearest town, Eliza looked out the window at the forest ranges below, plunging into dusk. Somewhere there, in the wilderness of the Kamemen Kihot tract, the forest had been keeping a terrible secret for five years, which people would now have to reveal.

At 11:45 p.m., the helicopter landed near the sheriff’s office in Weserve. Eliza was immediately escorted to Sheriff Caldwell’s office, where she spent an hour describing her find in detail. “The strangest thing is the carabiner,” she concluded. “It was set up as if someone wanted the bodies to be found, like a signpost.” The sheriff nodded, taking notes. He had aged ten years in five years. The case of the missing tourists, which had been bothering him all these years, had finally gotten a resolution. But this solution seemed to be the beginning of an even bigger mystery.

No one slept that night at the sheriff’s office. Officers were scurrying around the corridors. Phones were ringing, and more and more cars were pulling up to the building. And in a small motel on the outskirts of town, Eliza Reynolds couldn’t sleep for a long time, thinking about two young people whose dreams and plans were cut short in the depths of the San Isabel forest. The story she had accidentally discovered was only just beginning.

At dawn on May 19th, 2019, the Stone Claw turned into a veritable ant hill. Twenty people in uniform and civilian clothes carefully inspected every inch of the territory around the old spruce. Three specialists in white protective suits were carefully removing the gruesome discovery from the branch. Investigator Evan Drake, an experienced forensic scientist with 20 years of experience, was in charge of the operation. He personally supervised every stage of the evidence recovery, taking photos and documenting every detail.

“Careful with the rope,” he commanded at 7:20 a.m. when the technicians began lowering the bodies onto the tarp spread out below. Five years in the Colorado climate had changed the bodies beyond recognition. The skin and soft tissue had long since disappeared, leaving only bones connected by remnants of tendons. Clothes, once bright, had faded to an indeterminate gray-brown color. But even after five years of rain, snow, and wind, some things remained recognizable.

“A pink fleece jacket,” forensic scientist Dr. Rachel King noted quietly as the bodies were carefully placed on the tarp. “Looks like the description of Ara Marorrow’s clothing.” The second body had the remains of a dark t-shirt with a logo that could still be made out—National Geographic. It was the same t-shirt, according to the parents, that Aldrich wore. Dr. King began her examination without waiting for transportation to the lab. Time was too precious.

“Notice the rope,” she said, pointing to the synthetic cord that wrapped around the necks of both victims. “This is no ordinary clothesline. It’s a special climbing cord used for belaying. The tensile strength is about 4,000 lbs.” Evan Drake came closer, studying the knots. “A double-loop noose,” he noted. “Professional, not just a hasty tie.”

Meanwhile, forensic scientists examined the area around the tree. Microfiber brushes were used to carefully walk over the bark. Metal detectors combed the soil for any metal objects. Ultraviolet lights searched for traces of biological materials, although after all these years, the chances were minimal. At 10:15 a.m., investigator Drake called a meeting right at the crime scene. The helicopter was due to pick up the bodies in an hour, and they needed to summarize the preliminary results.

“So, here we go,” he began, opening his notebook. “Two victims, tentatively identified as Aldrich Wayne and Ara Marorrow, hanging in a noose from a tree branch for approximately five years. The cause of death is likely asphyxiation due to hanging, but an autopsy will confirm this. No signs of camping or tents in the vicinity. No personal belongings, backpacks, cameras.”

An interesting detail, Dr. King added. “The male skeleton has trauma marks on the neck that are inconsistent with hanging. It looks like blunt force trauma.”

“Was he unconscious when he was hanged?” the young officer asked. “Either stunned or dead,” King confirmed. “There are no such marks on the female skeleton.”

Evan Drake visibly tensed. “So, she could have seen her boyfriend being hanged or vice versa.” The doctor shrugged her shoulders. “It’s a question of sequence of events. Laboratory tests will give the answer.”

Meanwhile, one of the forensic scientists approached the group holding a transparent bag of evidence. “Found this 20 yards away under some leaves,” he said, pointing to a water bottle. “Colorado Springs label. Old but not five years old. Three or four months old at most.” Another fact that did not fit into the overall picture. “Who was in this remote place a few months before Eliza Reynolds found the bodies?”

The climbing carabiner with the blue ribbon also raised questions. It was thoroughly examined by experts who found that it had been installed no more than six months ago. The paint on the metal was still relatively fresh. “Someone wanted the bodies found,” Drake concluded. “But who and why now? Five years later.”

At 12:00 p.m., the bodies were carefully packed in special bags and transferred to a helicopter on a stretcher. They were sent to the morgue in Colorado Springs, where they were to undergo a full forensic examination. Investigator Drake remained on the scene, continuing to search for evidence. He personally examined the carabiner that Eliza had found between the rocks. “It’s strange,” he said to his assistant, Detective Ryan Foster, at 2:40 p.m. “Why would the killer hang them in such a prominent place? He could have just killed them and hidden them deeper in the woods where they would never be found.”

“Maybe it’s a warning,” Foster suggested. “You know how they used to hang pirates at the entrance to a harbor in the old days for others to see?” Drake nodded thoughtfully, looking at the area around him. His gaze settled on a rocky outcropping overhanging the hollow. “That ledge overlooks the entire tract,” he said. “An ideal vantage point for observation. Perhaps the killer wanted to admire his work.”

At 6:30 p.m., both groups reached their positions. Drake gave a signal on the radio, and the officers simultaneously moved to the quarry entrances. “Police, come out with your hands up!” Drake shouted into the loudspeaker as the group reached the main entrance. There was no response, only the echo of his own words and the rustling of leaves in the wind. The officers cautiously entered the dark attic, lighting the way with powerful flashlights.

The smell was the first thing that hit their nostrils—a mixture of dampness, mold, and something sweet that resembled marijuana. “He was here,” whispered one of the officers, shining his flashlight on the remains of the fire on the floor. The ashes were still warm.

In the depths of the attic chambers, they found a real living space—a cot, a forced air stove, water cans, and most importantly, a metal box with Aldrich and Ara’s personal belongings. “There’s their phones, their camera, their wallets,” Foster listed. A small dope plantation was found in a separate compartment of the attic. “He’s not just a killer,” Drake said quietly. “He’s a man who’s completely out of touch with reality.”

In the deepest corner of the attic, Drake ordered, “Send his picture to all the services.” But it was unlikely they’d catch him. “A man who lived five years invisible to the whole world will disappear completely.”

Two days later, the bodies of Aldrich and Ara were handed over to their families. The case was officially closed as solved, although the killer was never caught. “He left a sign and a confession because he knew he wouldn’t be found,” Drake said at the final meeting. The Silver Wind Quarry was sealed with concrete blocks. The spruce tree on which the bodies had been hanging for five years was cut down. But even now, many years later, locals try to avoid the Stone Claw tract. Some places in the Colorado mountains are forever branded with terrible secrets that the forest is in no hurry to reveal.

As time passed, the memories of Aldrich Wayne and Ara Marorrow faded into the background of local lore, but the mystery of their disappearance and the horror of their fate lingered like a dark cloud over the San Isabel National Forest. The forest, once a place of beauty and adventure, became a symbol of loss and tragedy, a reminder that beneath its serene surface lay the potential for darkness.

The families of the victims, while devastated, found strength in their shared grief. They became advocates for safety in the forests, pushing for better signage and awareness of the dangers that could lurk in the wilderness. They wanted to ensure that no other families would experience the same heartache they had endured.

In the end, the story of Aldrich and Ara serves as a haunting reminder of the fragility of life and the unexpected turns it can take. Their dreams, hopes, and future were stolen in an instant, leaving a void that could never be filled. The forest may have kept its secrets for years, but the truth eventually emerged, revealing the darkness that had claimed two young lives and the lives of those who loved them.

If you found this story compelling, please share your thoughts and reflections. What would you do in a similar situation? How do we ensure the safety of those we love in a world that can sometimes be so unpredictable? Let’s keep the conversation going about the importance of awareness and vigilance in our lives.