1935: R*cist Doorman Insults Bumpy Johnson at Whites-Only Club – What Happened Next Shocked New York

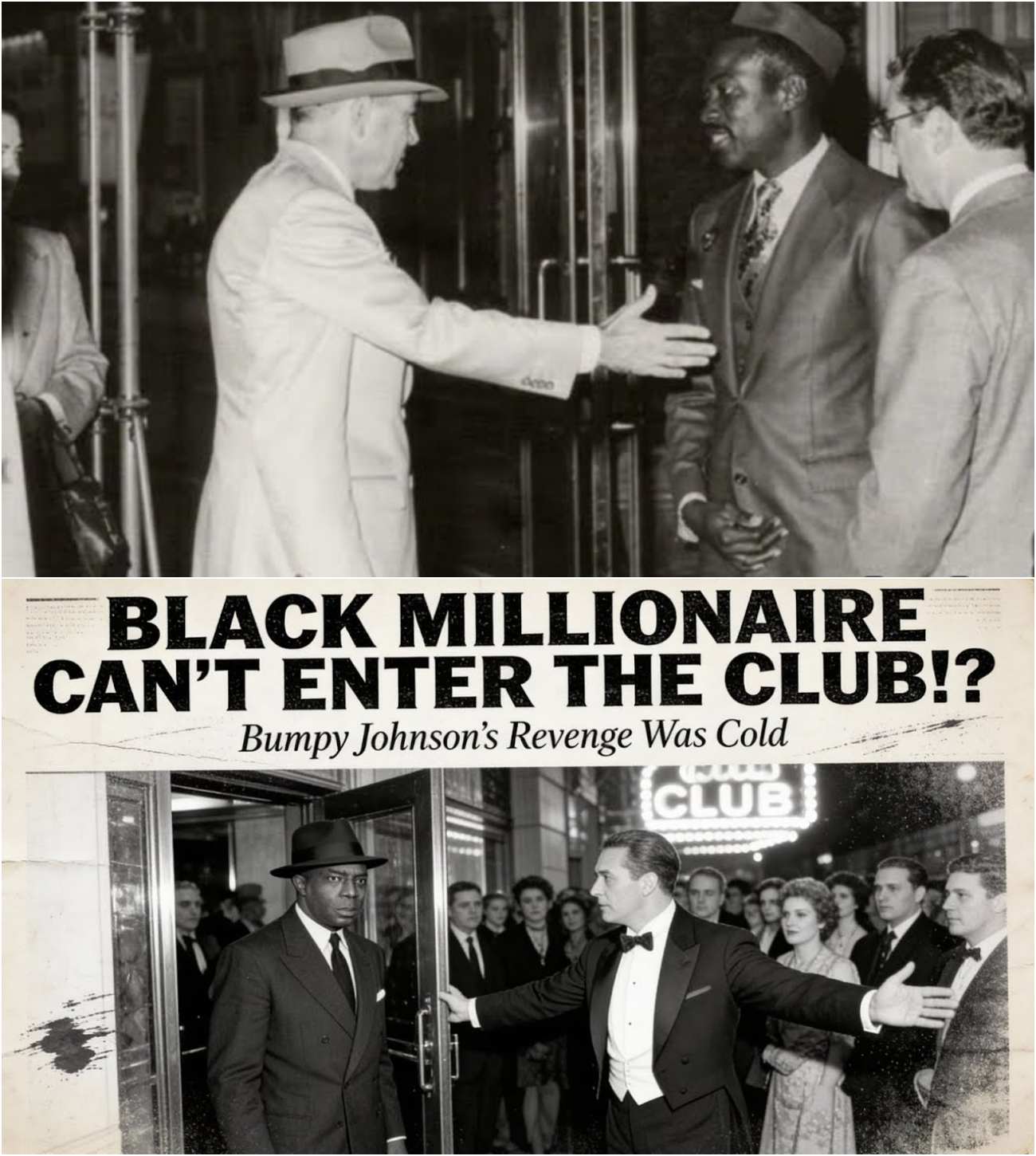

In the heart of Harlem, New York, a defining moment in history unfolded quietly, without the violence or explosions one might expect from such an iconic moment of resistance. On September 19, 1935, Ellsworth “Bumpy” Johnson, one of Harlem’s most powerful and respected figures, walked up to the entrance of the famed Cotton Club, dressed in a sharp navy blue suit, ready to discuss business with a trusted associate. But what should have been an ordinary night of networking in the most famous nightclub in Harlem, turned into a confrontation that would reverberate through the streets and backrooms of the community for decades to come.

The Cotton Club, a club known for its exclusive performances by African American musicians, had a notorious “whites-only” policy. Black performers were welcomed, but black patrons were not allowed to sit in the audience. This glaring contradiction in the heart of Harlem had existed for years, and Bumpy Johnson, for all his influence, had learned to navigate it. But on this particular evening, the doorman, Thomas Murphy, decided to enforce the club’s racist policy in the most humiliating way. Murphy stopped Bumpy Johnson, who had been invited by a Jewish businessman, and with a derisive tone, told him, “This club is for white patrons only. We don’t serve colorards here, except as entertainers and staff. Get back to Harlem where you belong.”

For Bumpy Johnson, this was not a personal affront. It was a systemic humiliation. Harlem had long been the cradle of black culture and creativity, but when it came to profiting from it, the powers that be—the owners of places like the Cotton Club—continued to profit from black talent while denying black people the dignity of being customers in their own neighborhood.

The Humiliation and Its Consequences

The insult stung, but Bumpy Johnson knew that reacting emotionally would give the white patrons a show they could talk about. Instead, he did the unexpected. He smiled—not a genuine smile, but one that carried the weight of cold calculation. Murphy, standing there, noticed a shift in Johnson’s demeanor. Bumpy didn’t argue or protest. He simply nodded once, turned around, and walked away. He knew that in this moment, silence was his weapon, and he had to be patient.

For the people watching—the 200 white patrons in line—the spectacle was over. They likely expected Johnson to cause trouble. But instead, he simply walked away. And for the next 15 minutes, as he walked through Harlem’s familiar streets, he began to realize that this insult wasn’t just about his personal humiliation. It was about the larger issue of black people’s systemic exclusion from establishments that profited from their very existence.

Bumpy Johnson had a vision, and it was one that would change Harlem forever.

Strategy Over Violence: The Quiet Revolution

Standing outside the Seavoy Ballroom, watching people enter a black-owned establishment that treated its patrons with respect, Johnson realized something profound. The Cotton Club, like so many other white-owned businesses in Harlem, had been extracting wealth from the community without giving anything back, except minimum-wage jobs and occasional performance opportunities. Black talent, black workers, and black culture were exploited, but black patrons—Harlem’s own people—were not allowed the privilege of sitting at the table.

Johnson understood that the Cotton Club was vulnerable in ways its owners had never considered. They could ignore the community, but the community had the power to hit them where it hurt the most: in their wallets. And if there was anyone who knew how to leverage economic power, it was Bumpy Johnson.

He made three phone calls that night. The first was to his trusted lawyer and adviser, Theodore “Teddy” Green. The second was to Stephanie St. Claire, the queen of the policy game who controlled substantial operations throughout Harlem. The third was to Adam Clayton Powell Sr., the influential minister of Abyssinian Baptist Church, who had spent years fighting discrimination but lacked the resources to challenge establishments like the Cotton Club.

Within hours, Bumpy had assembled a coalition of Harlem’s most influential figures. It wasn’t a group of revolutionaries with guns. It was a group of labor organizers, union officials, black professionals, and community leaders—people who had been humiliated in the same way, people who understood that their power had been underestimated. And together, they would make the Cotton Club pay for its arrogance.

The Economic Warfare That Changed Harlem

The plan was simple, yet sophisticated: economic sabotage. Rather than resorting to violence or direct confrontation, Johnson and his team would use the power of organized labor, supply chain disruption, and strategic community mobilization to cripple the Cotton Club’s operation. They would make it impossible for the club to continue operating under its racist policies.

The first step was to organize the black employees of the Cotton Club. Musicians, waiters, kitchen staff—all of them would be asked to participate in a coordinated strike. Johnson’s people would pressure the club’s suppliers to stop doing business with the Cotton Club. They would target the club’s weaknesses in every way possible, from labor issues to supply disruptions to political pressure. The goal was to create a situation where the Cotton Club either had to integrate or face a complete collapse of its operations.

The Plan in Action

By the following Monday, September 23, 1935, the groundwork was laid. Duke Ellington, the Cotton Club’s most famous performer, was on board. He threatened the club’s management with a 50% increase in his band’s pay and better working conditions. When they refused, he made it clear that he had offers from other venues and would leave if the demands weren’t met.

Meanwhile, Johnson’s associates in Harlem began organizing. Kitchen staff started working slower, subtly reducing efficiency. Waiters made mistakes that frustrated the white patrons without giving them grounds for firing anyone. Suppliers experienced delays, misfilled orders, and problems with deliveries. All of these actions, while seemingly small and unnoticeable, began to pile up, making the club’s operations increasingly expensive and inefficient.

As the pressure built, the Cotton Club’s owners started to notice. They reached out to their political connections, trying to identify the source of the disruption. But none of their usual methods worked. When they contacted gangsters from outside Harlem to apply pressure, they found that Johnson’s network had a stranglehold on Harlem that they could not penetrate. The balance of power had shifted, and the Cotton Club’s owners had no choice but to concede.

Victory Without Violence

On October 15, 1935, Oni Madden, the owner of the Cotton Club, issued a public statement: The Cotton Club would no longer refuse service based on race. Black patrons would be allowed to enter and enjoy the performances they had been excluded from for so long.

The decision sent shockwaves through Harlem. The Cotton Club, the most famous white-only establishment in the neighborhood, had been forced to integrate. And the victory didn’t stop there. The methods used to break the Cotton Club’s color barrier were quickly applied to other discriminatory establishments across Harlem. Within months, black entertainers were performing in integrated venues, and black patrons were being welcomed in places that had once been off-limits to them.

A Legacy of Change

Bumpy Johnson’s response to being humiliated at the Cotton Club was not about violence or immediate retaliation—it was about strategy. His quiet walk away from the club’s door, followed by the strategic application of economic pressure, led to the integration of one of Harlem’s most iconic institutions and helped pave the way for future civil rights movements.

What Johnson proved in 1935 was that organized economic power could bring about change in ways that moral appeals and legal challenges couldn’t. The methods he pioneered would be used by civil rights activists for decades to come. His story is a reminder that sometimes the most powerful victories come not from physical confrontation, but from patience, planning, and the ability to leverage what you already have.