1965: A Ra*ist TV Host Insulted Bumpy Johnson, Bumpy Laughed — Then the Host Lost Everything

In 1965, the city of New York was a powder keg, ready to ignite. The civil rights movement was sweeping across the nation, challenging the status quo and tearing at the seams of a society steeped in racial injustice. In Harlem, the streets were alive with tension, vibrating with the energy of change. At the center of this storm stood Ellsworth “Bumpy” Johnson—a man revered by some and reviled by others.

To the police, Bumpy was a plague, a gangster who had choked the city with his numbers racket and iron-fisted control. But to the people of Harlem, he was a protector, a provider, a figure who stood tall when the world wanted him on his knees. This complicated legacy made him a target for those who sought to undermine his influence, including Julian Westbrook, the star anchor of the City and Focus evening news program.

Westbrook was the face of New York media, a man cut from marble and privilege, with a jawline that could slice through glass. He sat behind his mahogany desk at Rockefeller Center, delivering news to the good people of the suburbs, dictating who to fear and what to think. He was arrogant, untouchable, and deeply racist—not with burning crosses, but with a sneer disguised as a smile and questions that were more like accusations.

#### The Setup

The idea for the interview had come from Westbrook himself. The network was losing ground to younger, edgier broadcasts that reported from the front lines of protests, and Westbrook needed a spectacle. He wanted to drag Bumpy Johnson out of the shadows and into the harsh light of the studio. His plan was to strip Bumpy of his power, to expose him as a savage, uneducated thug, and to end the legend of Bumpy Johnson once and for all.

He pitched the interview as a public service—a hard-hitting expose on organized crime—but in the privacy of his office, he had been more honest. “I’m going to break him,” he had said, swirling a scotch for his producer. “I’ll make him lose his temper, and when the world sees the animal come out, the police will finally have the mandate to lock him away forever.”

When the invitation arrived at Bumpy’s Lennox Terrace apartment, his lieutenants were unanimous: do not go. They sensed a trap. They knew that a man like Westbrook didn’t invite a man like Bumpy for tea; he invited him for execution. “He controls the microphone,” whispered his longtime confidant, a man named Whispers. “He controls the cameras. You go down there into his house, and you’re playing by his rules. He’ll cut you up.”

Bumpy sat in his armchair, reading the invitation printed on thick cream-colored cardstock—elegant and insulting in its formality. He smoked his cigar slowly, the blue smoke drifting toward the ceiling. He knew Whispers was right; it was a trap. But Bumpy had spent his entire life walking into traps and dismantling them from the inside. He understood that declining the interview would be seen as cowardice, a sign of fear. And if there was one thing Bumpy Johnson would not tolerate, it was the perception of fear.

“I’m going,” Bumpy said, his voice low and final. “He thinks he’s inviting a gangster. He thinks he’s going to talk to a caricature. He doesn’t know he’s inviting a man who reads Nietzsche and plays chess. Let him set his trap. I’ll bring the bait.”

#### The Day of Reckoning

The day of the interview was unseasonably cold. The wind whipped down the avenues of Manhattan, cutting through coats and stinging faces. Bumpy dressed with the precision of a general preparing for battle, choosing a charcoal gray suit tailored in Italy, a crisp white shirt, and a deep burgundy silk tie. He placed his fedora on his head at the exact angle that signaled authority. When he checked his reflection, he didn’t see a thug; he saw a senator, a captain of industry—exactly what Westbrook feared most: an equal.

The drive from Harlem to Midtown was a journey between two worlds. As the black Cadillac moved south, crossing the invisible border of 110th Street, the landscape changed. The brownstones and bustling street corners of Harlem gave way to the towering steel canyons of corporate America. The faces on the sidewalk shifted from black and brown to white, and the energy transformed from the rhythm of jazz and survival to the cold, frantic pace of commerce.

When the car pulled up to the studio entrance at Rockefeller Center, hostility was immediate. The doorman, a heavyset man in a uniform with gold braid, hesitated before opening the car door. He looked at Bumpy, then at the driver, then back at Bumpy, his lip curling slightly. He opened the door but didn’t offer a hand or say, “Good evening, sir.” His body language screamed that Bumpy didn’t belong there.

Ignoring the man, Bumpy stepped out of the car and walked into the lobby, his entourage trailing behind. The lobby was a cathedral of marble and gold, echoing with the footsteps of secretaries and executives. As Bumpy entered, the noise dropped, heads turned, and eyes widened. It was rare for a Black man to walk through these doors, unless he was carrying a mop or a tray of coffee.

The receptionist, a young woman with a tight smile and terrified eyes, greeted him. “Mr. Johnson,” she squeaked. “Mr. Westbrook is expecting you. Security will need to check you.” Two security guards stepped forward, big men, ex-cops with hands resting near their belts, looking at Bumpy with open aggression. One of them, a man with a red face and a thick neck, stepped into Bumpy’s personal space.

“Standard procedure,” the guard grunted. Nat Pedigrew, Bumpy’s bodyguard, stepped forward, fists clenching, but Bumpy raised a hand to stop him. He turned to the guard, his voice calm but firm. “I am a guest of Mr. Westbrook. I was invited here. I am unarmed. My men are unarmed. If you touch me, I will turn around and walk out that door, and your boss will have three million people staring at an empty chair tonight. I suspect by tomorrow morning, you will be looking for work on the docks.”

The guard hesitated, glancing at the receptionist, who was pale, and at the clock. The show was live in 40 minutes. He knew Westbrook would flay him alive if the guest walked out. The guards stepped back, grumbling, their faces flushing deeper shades of red. “Right this way,” the receptionist whispered, hurrying out from behind the desk.

They were led down long carpeted corridors lined with portraits of famous white men—anchors, politicians, actors. Every time they passed a door, the typing stopped, and faces appeared in the glass. The whispers followed them like a wake behind a ship. “That’s him. That’s the gangster. That’s the killer.”

They were shown to a green room, small and painted a sickly shade of beige, with a bowl of stale fruit on the table. The contrast was deliberate. Bumpy knew that the green rooms for senators and movie stars were plush, filled with champagne and flowers. This room was a cell, designed to make him feel small and remind him of his place before he went on stage.

Bumpy didn’t sit; he stood in the center of the room, examining the walls. Ten minutes later, the door opened, and Julian Westbrook walked in. In person, Westbrook was taller than he appeared on television, immaculately groomed, his hair cemented into place with pomade, his teeth blindingly white. He smelled of expensive cologne and arrogance.

He didn’t come in to welcome a guest; he came in to inspect a specimen. “Mr. Johnson,” Westbrook said, standing near the door, keeping a barrier of air between them. “I’m glad you decided to show up. Frankly, we had a backup segment on the botanical gardens ready to go. We weren’t sure you’d have the nerve.”

“I have never been accused of lacking nerve, Mr. Westbrook,” Bumpy replied, turning to face him. Westbrook chuckled, devoid of humor. “Yes, well, the streets are one thing. This is national television. It’s a different arena. There are rules here—decency, decorum. I just wanted to come down here and make sure we understand each other.”

Westbrook took a step closer, his voice dropping to a patronizing tone, the way one might speak to a slow child or a trained dog. “We’re going to talk about Harlem. We’re going to talk about the numbers, the violence, the drugs. I want straight answers. No street slang, no jive talk. Speak clearly. The audience out there isn’t used to your dialect. We don’t want to have to subtitle you.”

It was a slap in the face, a calculated, brutal insult wrapped in the guise of production advice. Westbrook was calling him illiterate, calling him a savage. Bumpy’s expression didn’t change. He didn’t frown or glare; he simply looked at Westbrook with mild curiosity, as if he were observing a bug crawling across a picnic table.

“I will do my best to make myself understood, Julian,” Bumpy said, using the anchor’s first name deliberately—a breach of protocol, a subtle power move. Westbrook’s eye twitched. He hated being called Julian by anyone, let alone a criminal.

“Mr. Westbrook,” he corrected sharply. “On air, it’s Mr. Westbrook.” “We’ll see,” Bumpy replied, and Westbrook stared at him for a moment, trying to find a crack in the armor, trying to see the anger. He found nothing. With a scoff, he turned and left the room.

“Five minutes to air. Don’t be late.” When the door closed, Nat Pedigrew let out a low growl. “Let me break his jaw, Bumpy. Just one hit. He won’t be talking so pretty with his teeth in his throat.”

“No,” Bumpy said, adjusting his cufflinks. “That’s what he wants. He wants the brute. He wants the animal. If I hit him, he wins. If I yell, he wins. Tonight, Nat, we aren’t going to fight him with fists. We’re going to kill him with the truth. And the truth hurts a man like that far more than a punch ever could.”

A stage manager, a young man with a headset who looked terrified, appeared at the door. “Mr. Johnson, we’re ready for you.” Bumpy walked out of the green room and onto the studio floor. The transition was blinding. The studio was a cavernous space filled with massive cameras on wheels, boom microphones hanging like predatory birds, and banks of lights generating a physical heat.

Beyond the lit circle of the set sat the audience—300 people, almost entirely white. They sat in the risers, murmuring, craning their necks to see the monster from Harlem. Westbrook was already seated behind his desk, reviewing his notes. He looked commanding, the master of his domain. There was a chair positioned opposite him, a simple unpadded wooden chair—another subtle insult.

Bumpy walked onto the set, and the audience went silent. The sound of his footsteps on the polished floor was the only noise in the room. He sat down in the wooden chair, crossed his legs, and folded his hands in his lap. He looked comfortable. He looked regal. A makeup woman rushed in to dab powder on Westbrook’s nose. She hesitated near Bumpy, holding a sponge.

“I’m fine, darling,” Bumpy said gently. “I don’t wear a mask.” Westbrook heard it and bristled. The stage manager began the countdown. “30 seconds. Quiet on the set. 20 seconds.” The red lights on the cameras hummed to life. The floor director pointed a finger at Westbrook. “Good evening,” Westbrook said, his voice instantly transforming into the smooth, trusted baritone that America loved.

“I’m Julian Westbrook, and this is City in Focus. Tonight, we have a special and frankly controversial program. We take you inside the dark heart of Harlem—a world of shadows, vice, and violence. And we have with us the man who claims to be its mayor, but whom the police call its cancer, Mr. Ellsworth Johnson. They call him Bumpy.”

Westbrook turned to Bumpy, his face hardening into a mask of serious journalistic inquiry. “Mr. Johnson,” he began, not wasting a second. “Thank you for coming, although I suppose I should check my wallet before we begin.” A ripple of laughter went through the audience. A cheap joke, a stereotype right out of the gate.

Westbrook smirked, pleased with himself. He had established dominance early and marked Bumpy as a thief. Bumpy didn’t smile or laugh; he waited for the laughter to die down. “You can check your wallet if you like, Mr. Westbrook, but I believe you’ll find that the only people in this city who steal from the poor are the ones sitting in the banks downtown, not the ones in Harlem.”

The audience went quiet. The laughter died in their throats. Westbrook’s smile faltered for a fraction of a second. He hadn’t expected a retort or a political pivot. “Very clever,” Westbrook said, dismissing the comment. “But let’s talk about facts. You present yourself as a businessman, a community leader, but the police records tell a different story. They say you are a predator. They say you run a numbers racket that drains the savings of the very people you claim to protect.”

“How do you justify taking milk money from starving families so you can buy Italian suits?” Westbrook gestured to Bumpy’s clothes with a sneer. Bumpy leaned forward slightly. “The numbers game, Mr. Westbrook, is the poor man’s stock market. Wall Street gambles with millions every day, and when they crash the economy, the government bails them out. When a Black woman in Harlem puts a dime on a number, hoping to win enough to pay her rent, the police kick down her door.”

“Why is gambling a business downtown, but a crime uptown?” Bumpy continued, his voice steady. “Because it’s against the law, Westbrook snapped. And because it brings violence, murders, shootings in the street. You are responsible for the blood on the sidewalks of Harlem. Do you deny that men have died on your orders?”

“I deny that I am the cause of the violence,” Bumpy said calmly. “The violence in Harlem is born of poverty, born of despair, born of a system that refuses to hire a Black man for anything other than sweeping a floor.”

“You want to talk about blood, Mr. Westbrook? Let’s talk about the blood on the hands of the landlords who refuse to fix the heat in the winter. Let’s talk about the blood on the hands of the police who beat teenagers for walking down the wrong street. I don’t create the jungle; I just learned how to survive in it.”

Westbrook was getting annoyed. Bumpy wasn’t following the script. He was supposed to be defensive and angry, but instead, he was turning the interview into an indictment of society. Westbrook decided to take the gloves off. He needed to hurt him, to humiliate him.

“You talk a lot about society,” Westbrook said, his voice dripping with venom. “But isn’t it true that you are nothing more than a parasite? You poison your own people. You sell them dreams that never come true. And let’s be honest, Mr. Johnson, you’re not an educated man. You spent your youth in prison, not in a library. You are a thug who got lucky. Do you really think you have the intellectual capacity to sit here and lecture me about economics?”

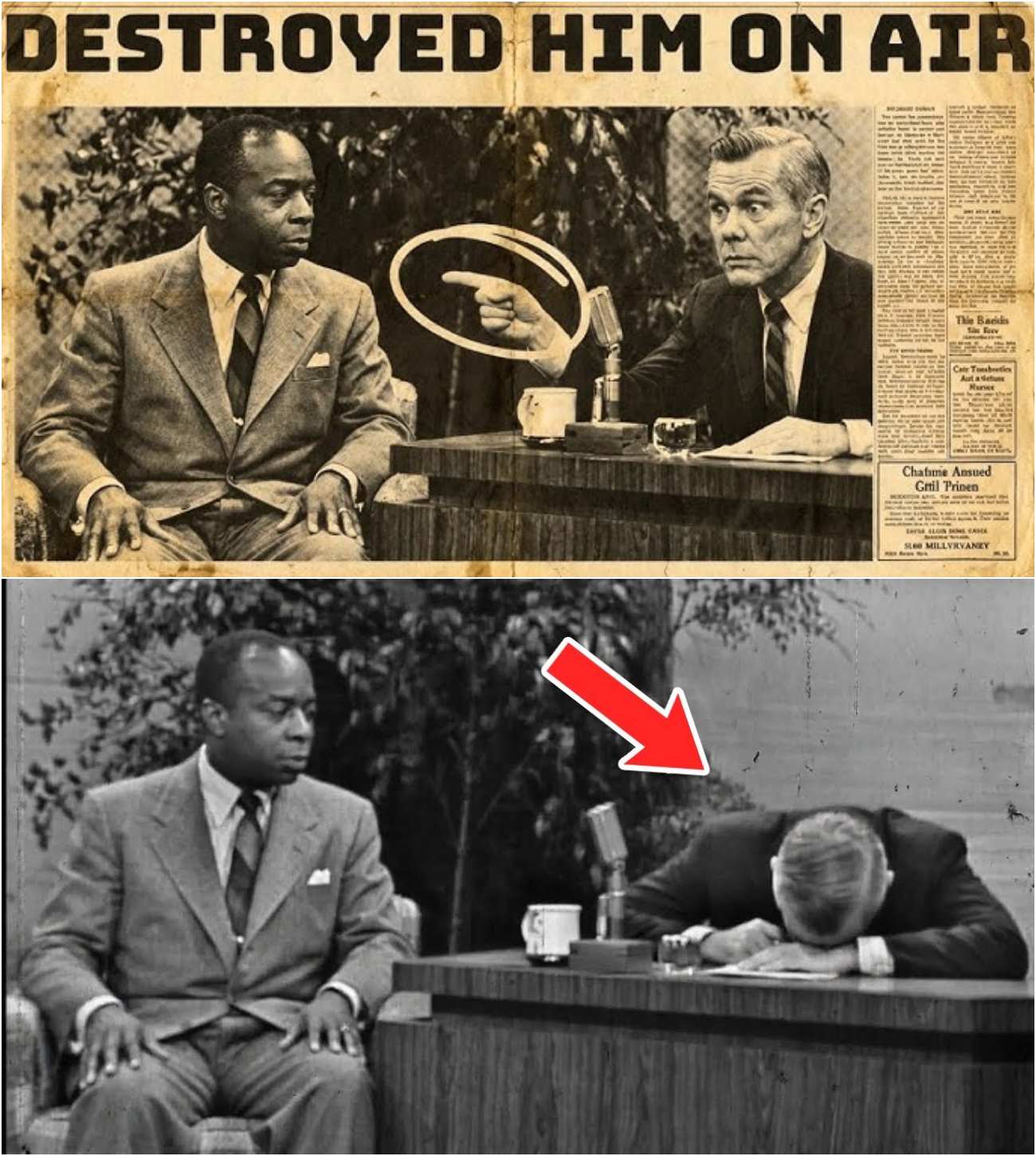

It was a direct attack on Bumpy’s intelligence, a thinly veiled insult that dripped with condescension. The studio felt electric. The audience leaned in, waiting for Bumpy to snap, wanting the shout, the threat. Bumpy stared at Westbrook, and for a long moment, he said nothing, allowing the silence to stretch and making Westbrook squirm.

“I may not have a degree from Harvard, Mr. Westbrook,” Bumpy said softly, “but I have a degree from Sing. I have a degree from the streets where you wouldn’t last ten minutes. And as for reading, I suspect I have read more books in my cell than you have read in your entire life. You read teleprompters; I read history. And history teaches me that men like you always think they are the masters of the world right up until the moment the world changes.”

Westbrook’s face turned pink. He was losing control. The interview was slipping away, and he realized he had underestimated the man in front of him. He needed the nuclear option. He needed to ask the question that would break Bumpy Johnson. He had saved it for the end, but he had to use it now.

Leaning in with a cruel, predatory glint in his eyes, Westbrook lowered his voice, making it sound intimate, concerned, and utterly vicious. “Let’s talk about your family, Bumpy. Let’s talk about your daughter. You parade her around like a princess. You send her to fancy schools. But everyone knows the truth. Everyone knows that no matter how much money you spend, no matter how many dresses you buy her, she will never be accepted. She will always be the daughter of a criminal, the daughter of a primitive.”

“Do you really think,” Westbrook paused, letting the words hang in the air like poison gas, “that you can wash the stain of your black blood off of her with dirty money? Do you think she isn’t ashamed of what you are?”

The air left the room. It was a line that should never have been crossed. It wasn’t journalism; it was a hate crime broadcast live to three million homes. It was an attack on a man’s child, on his race, and on his soul. The audience gasped, and even the camera operators froze. It was a moment of supreme cruelty.

Westbrook sat back, a smug smile playing on his lips. He had done it; he had pushed the button. Now he waited for the explosion, for Bumpy to leap across the desk, to scream, to validate every racist stereotype Westbrook held dear. But Bumpy Johnson went very, very still.

The calm that descended on him was not the calm of peace; it was the calm of the eye of a hurricane—the terrifying stillness of a predator deciding exactly where to sink its teeth. He looked at Westbrook, not blinking, his eyes reflecting the studio lights like obsidian.

Slowly, deliberately, Bumpy reached into his inside pocket. The security guards tensed, hands moving to their holsters. But Bumpy didn’t pull out a gun; he pulled out a silver cigarette case. He opened it, took out a match, and struck it. The flame flared bright and hot as he lit his cigar, taking a long drag and exhaling a cloud of smoke that drifted across the desk, enveloping Westbrook’s face.

Bumpy leaned forward through the smoke, his voice dropping to a register that vibrated in the chests of everyone in the room. “You made a mistake, Julian,” Bumpy whispered. “You thought you were interviewing a man who wanted your approval. You thought you could shame me. But you forgot one thing.”

Bumpy smiled, and it was the most terrifying smile Julian Westbrook had ever seen. “You forgot that I don’t care about your rules. And you forgot that we are on live television, which means there is no one here to save you from the answer I am about to give you.”

Bumpy checked his watch. “We have three minutes left. Good. That’s just enough time.” The producer in the booth was screaming into Westbrook’s earpiece, “Cut to commercial! Cut to commercial!” But Westbrook was frozen, paralyzed by the look in Bumpy Johnson’s eyes. He couldn’t speak or move; he had opened a door to a room he was not prepared to enter, and now the door had locked behind him.

Bumpy took another drag of the cigar, the ash glowing red. “You want to know about the real reason you sit in that chair, Julian?” Bumpy asked, addressing the camera now, looking directly into the lens. “You told the world that I prey on the weak. You told them I exploit the desperate. And let’s be honest, Mr. Westbrook, you’re not an educated man. You spent your youth in prison, not in a library. You are a thug who got lucky. Do you really think you have the intellectual capacity to sit here and lecture me about economics?”

Westbrook’s mouth opened, but no sound came out. His throat had constricted, dry as dust. He knew the truth of Bumpy’s words; he was a man caught in a web of his own making. “Stop it. This is slander. I’ll sue you,” he finally managed to stammer.

“Slander is a lie, Julian,” Bumpy said, tapping the piece of paper he had placed on Westbrook’s desk. “This is a receipt dated last Tuesday. $50,000. That’s what you owe S.”

Westbrook’s eyes widened in genuine panic. “You talk about the numbers game in Harlem like it’s a sin. You look down your nose at a grandmother putting a dime on 714, hoping to buy a new coat. But you, Mr. Westbrook, you like the ponies, don’t you? You like the track at Saratoga. And you like the private card games at the Plaza Hotel.”

Westbrook found his voice, but it was a strangled, desperate whisper. “Stop it. This is slander. I’ll sue you.”

Bumpy continued, “You see, I know a man in Hell’s Kitchen. His name is S. You know S, don’t you, Julian? S is a businessman much like myself. He lends money to men who live beyond their means—men who need to keep up appearances, men who wear $300 suits and drive Jaguars but haven’t paid their rent in four months.”

Westbrook’s face was drained of color, his makeup standing out like orange paint on a corpse. “You talk about the numbers game in Harlem as if it’s a crime, but you’re doing the same thing in your own world. You’re just better at hiding it.”

The audience gasped, a collective intake of breath that sucked the oxygen out of the room. This wasn’t just an accusation; it was a dissection. Bumpy was peeling back the layers of Westbrook’s carefully constructed life, exposing the rot underneath. “You didn’t bring me here to expose the truth about Harlem,” Bumpy said, his voice hardening. “You brought me here to save your own skin. You thought if you humiliated Bumpy Johnson, if you destroyed the black menace on live TV, you’d be the hero of New York. You’d get your bonus, you’d pay off S. You’re not a journalist, Mr. Westbrook. You’re a junkie. You’re a degenerate gambler trying to settle a debt with my reputation.”

Westbrook was shaking now, visibly shaking. The sweat was beating on his forehead, cutting through the powder. He looked at the camera, then at Bumpy, his eyes pleading. He was begging without saying the words. “Please stop. Please don’t ruin me.”

But Bumpy Johnson was not a man of mercy; he was a man of justice. And justice on the streets of Harlem was absolute. “You mentioned my daughter,” Bumpy said, his voice dropping to a low growl. “You asked if she was ashamed of me. You asked if my dirty money could wash off her skin.”

Bumpy stood up, rising slowly, unfolding his frame until he towered over Westbrook. He picked up the gambling slip and dropped it onto Westbrook’s lap. “My daughter knows exactly who I am. She knows I am a man who keeps his word. She knows I am a man who pays his debts. And she knows that I would never, ever sell my soul to a loan shark to buy a suit I couldn’t afford.”

Bumpy leaned down, his face inches from Westbrook’s. The anchor smelled the tobacco, the peppermint, and the terrifying scent of raw power. “My daughter sleeps soundly at night, Julian. But your son, when he goes to school tomorrow and the other children ask him why his father is a fraud who owes money to the mob, I wonder if he will be ashamed of you.”

Westbrook broke. “Cut the feed!” he screamed, his voice cracking into a high-pitched shriek. He scrambled backward, his chair tipping over and sending him sprawling onto the polished floor. “Cut it! Cut it now! Security! Get him out of here!” He lay on the floor, tangled in his expensive suit, pointing a shaking finger at Bumpy. He looked pathetic, small—the giant of journalism, the voice of the city, reduced to a frightened child throwing a tantrum in the dirt.

The red light on the camera finally blinked off. The studio went dark as the director cut to a commercial for laundry detergent, but the damage was done. Three million people had seen Julian Westbrook fall. They had seen the King of Harlem stand tall while the pillar of society crumbled.

In the sudden dimness of the studio, chaos erupted. The stage manager rushed forward, and the security guards, finally released from their paralysis, stepped onto the set, hands on their holsters. “Mr. Johnson,” the lead guard barked, though his voice lacked the conviction it had held in the lobby. “You need to leave now.”

Bumpy didn’t look at the guard; he looked down at Westbrook, who was trying to stand up, his hands slipping on the sleek floor. Bumpy reached into his pocket one last time. Westbrook flinched again, expecting a gun, a knife—anything. Instead, Bumpy pulled out a single crisp $100 bill and let it flutter down, landing on Westbrook’s chest. “For a cab,” Bumpy said. “Since Sal is going to take your car.”

Bumpy turned his back on the wreckage, adjusted his cuffs, checked the knot of his tie, and began to walk toward the exit. Nat Pedigrew and Whispers materialized from the wings, flanking him like stone gargoyles. They moved in a phalanx, a wedge of dark suits cutting through the panicked studio staff.

The audience, which had been silent for the entire broadcast, began to move slowly at first, then all at once. They stood up, not to boo or cheer, but to watch him go with a mixture of fear and awe. They had come expecting to see a monster; they were leaving having seen a man who possessed a dignity they couldn’t comprehend.

As Bumpy walked through the lobby, the atmosphere had changed entirely. The receptionist was no longer smiling; she was staring at him with wide saucer eyes. The doorman, who had hesitated to open the car door, rushed forward now, pushing the revolving door open with a deferential bow, sweating nervously. “Have a good night, Mr. Johnson,” the doorman stammered.

Bumpy paused and looked at the man. “You, too, son. Try not to judge a book by its cover. Sometimes the cover is expensive, but the pages are blank.” They stepped out into the cold night air. The wind whipped down Sixth Avenue, but Bumpy didn’t feel it. He felt the heat of victory radiating from his chest.

They got into the back of the Cadillac, the heavy door slamming shut and sealing out the noise of the city. For a long time, no one spoke. The car moved north, the lights of the city blurring past. Nat was the first to break the silence. “Bumpy,” Nat said, shaking his head. “I have seen you do some cold things. I’ve seen you break fingers. I’ve seen you order hits. But that— that was murder.”

Whispers chuckled in the front seat, a dry rattling sound. “Did you see his face when you dropped the marker? I thought he was going to have a heart attack right there on the rug.”

Bumpy lit a fresh cigar. “He killed himself. Nat, I just provided the mirror. Men like Westbrook, they build their castles on sand. They think because they are white and rich and famous that the rules don’t apply to them. They think they can look down on us. But gravity applies to everyone. And the higher you build your tower on a lie, the harder it falls when someone kicks out the foundation.”

“Where did you get the marker?” Nat asked. “S usually keeps his books tight.”

Bumpy smiled in the darkness. “S does keep his books tight. But S also operates in a territory that borders ours. He needed a favor last week—some trouble with a union rep who wouldn’t play ball. I handled it for him. He owed me. When I saw Westbrook’s name on the invitation, I made a call. I asked S if our friend Julian had any outstanding liabilities. S was more than happy to trade the debt for a clean slate with me.”

“So you bought his debt?” Whispers asked.

“I bought his soul,” Bumpy corrected. “And tonight, I cashed it in.”

The car crossed 110th Street, and the rhythm of the city changed again. The stiffness of Midtown melted away, replaced by the vibrant, struggling pulse of Harlem. People were out on the streets despite the cold. As the Cadillac rolled down Lennox Avenue, Bumpy saw something he hadn’t expected. People were cheering. They were standing on the corners, pointing at the car, clapping as a group of young men outside a pool hall raised their fists in the air.

They had seen the broadcast. They had witnessed Bumpy Johnson walk into the lion’s den and skin the lion alive. For years, the media had told them they were nothing, that they were criminals, that they were less than. Tonight, one of their own had gone onto the white man’s stage and proven that intelligence and power were not determined by the color of a man’s skin.

Bumpy watched them through the window, not waving. He wasn’t a politician running for office; he was a king returning from a crusade. But his eyes softened. Yes, he did it for himself, for Analisa, but in doing so, he had given Harlem a victory it desperately needed.

When he arrived at the apartment, Elise was waiting for him. She was sitting on the sofa, the television still on. The news station had switched to a rerun of a sitcom, frantically trying to fill the dead air left by Westbrook’s meltdown. Elise stood up as Bumpy walked in, wearing her nightgown with her hair wrapped in a silk scarf. Her eyes were red, but she wasn’t crying anymore.

“You didn’t have to do that,” she whispered. “You made him hate you.”

Bumpy took off his coat and handed it to Nat, who retreated to the kitchen to give them privacy. He walked over to his daughter, looking at her face—the face so much like her mother’s, the face he would burn the world down to protect. “He already hated me, baby girl,” Bumpy said gently. “He hated me before I walked in the door. He hated me because I exist. What I did tonight wasn’t about making him hate me. It was about making him respect you.”

“He said terrible things,” Elise said, her voice trembling. “About me, about us.”

“He said what he thought, Elise. And the world saw him for it. They saw the hate, and then they saw the cowardice. You cannot kill hate, my dear. It is a weed that grows in the heart. But you can expose it. You can shine a light on it so bright that it withers.”

That night, the phone rang—a shrill, jarring sound in the quiet apartment. Bumpy looked at it, knowing who it would be. It would be the other bosses, the Italians, the politicians, everyone wanting to know if Bumpy Johnson had truly just ended a man’s career on live television. Bumpy ignored it, sitting down on the sofa next to his daughter.

“Turn it off,” he said, gesturing to the TV. Elise clicked the dial, silencing the noise of the world. “Did you really pay his cab fare?” she asked, a small smile finally touching her lips.

“I did. A man should always be charitable to the less fortunate.”

The fallout from the broadcast was swift, brutal, and total. By the next morning, Julian Westbrook was not just unemployed; he was radioactive. The network issued a statement before dawn announcing Westbrook’s immediate resignation due to personal health reasons. They wiped his name from the marquee and scrubbed his picture from the hallways. The gambling debt story ran in every newspaper in the city—the Post, the Daily News, even the Times carried the story of the anchor’s secret life. The revelation of his hypocrisy destroyed any sympathy he might have garnered.

If Bumpy had punched him, Westbrook would have been a martyr, a victim of savage violence. But because Bumpy had used the truth, Westbrook became a pariah. He was the man who preached morality while living in the gutter.

Westbrook lost his apartment and his car. His wife left him within the week, taking the children to her parents’ estate in Connecticut. He tried to sue, but no lawyer would take the case. The evidence was irrefutable, and more importantly, no one wanted to go up against Bumpy Johnson in open court.

Three weeks later, Bumpy was sitting in the Flash Inn, eating a steak. The restaurant was crowded, filled with the smoke and laughter of Harlem’s elite. The jukebox was playing Coltrane, and the atmosphere was warm, safe, and victorious. Whispers walked in, shaking the rain off his umbrella. He slid into the booth opposite Bumpy. “You hear about Westbrook?” Whispers asked, pouring himself a drink.

“I don’t follow the gossip columns,” Bumpy replied, cutting his meat.

“Not in the columns,” Whispers said. “Saw him downtown near the Port Authority. And he looks rough. His suit was wrinkled. Looked like he hadn’t shaved in days. He was trying to get into a card game in the back of a deli. They threw him out, said his credit was no good.”

Bumpy chewed slowly, swallowed, and took a sip of his red wine. “Did he ask for me?” he inquired.

“No, but he looked terrified. He keeps looking over his shoulder. I think he thinks you’re going to send someone after him.”

“Finish the job,” Bumpy shook his head. “There’s no need to finish a job that’s already done. A man like that needs an audience to exist. Without the camera, without the chair, without the admiration, he’s already dead. He’s just a ghost haunting a city that forgot his name.”

Still, Whispers grinned. “It was a hell of a thing. The instant regret seen round the world. The boys are still talking about it. My daughter sleeps soundly. Does your son?”

That line cut deep. Bumpy wiped his mouth with his napkin and looked out the window of the restaurant at the rain-slicked streets of Harlem. He saw the people walking by—those who struggled, fought, and had been told for centuries that they were less than the Westbrooks of the world.

“He asked the wrong question,” Bumpy said quietly. “He asked if my daughter was ashamed. He should have asked if I was afraid, because if he had asked that, I would have told him the truth.”

“And what’s the truth?” Whispers asked.

Bumpy looked at his friend, his eyes hard and clear. “The truth is, I’m not afraid of the police. I’m not afraid of the Italians. And I am certainly not afraid of a man with a microphone. The only thing I fear is a world where my daughter thinks she has to lower her head to anyone. And as long as I have breath in my body, I will make sure that world never exists.”

He signaled the waiter for the check. “Come on,” Bumpy said, standing up and putting on his fedora. “We have work to do. The numbers don’t run themselves, and I suspect S might be looking for a new customer in Hell’s Kitchen. I hear there’s a vacancy in the broadcasting industry.”

As they walked out of the Flash Inn and into the night, the King of Harlem and his shadow left the ghost of Julian Westbrook far behind in the darkness. It was a cautionary tale for anyone who dared to mistake Bumpy Johnson’s silence for submission.

The city moved on, but the lesson remained, burned into the static of the airwaves: you can come for the king, but you best not miss. And you certainly, absolutely, best not insult the princess.