“Abort, Abort—He’s Too Fast!” — German Radios Collapsed as a Rookie in a P-51 Escaped 9 FW-190s

They called him Baby Face, a 19-year-old replacement pilot fresh from stateside training, sent to the most brutal fighter group in the 8th Air Force. He landed at Debbon on a cold March morning in 1944. His log book is thin, his combat experience non-existent. The squadron commander looked him over and shook his head.

The mechanics laughed. Within 6 hours, he would be alone above Germany, surrounded by nine FWolf 190s with no wingman and no way out. March 1944, the air war over Europe had become an industrial slaughterhouse. Every day, hundreds of American bombers crossed into German airspace. And every day, the Luftvafa rose to meet them.

Fighters twisted and burned at 25,000 ft. Parachutes blossomed like dandelions over farmland. Young men died before they learned the names of their bunkmates. The 8th Air Force was bleeding pilots faster than training schools could replace them. Boys who had been flying crop dusters a year earlier were now expected to dogfight veteran German aces in some of the most unforgiving skies on Earth.

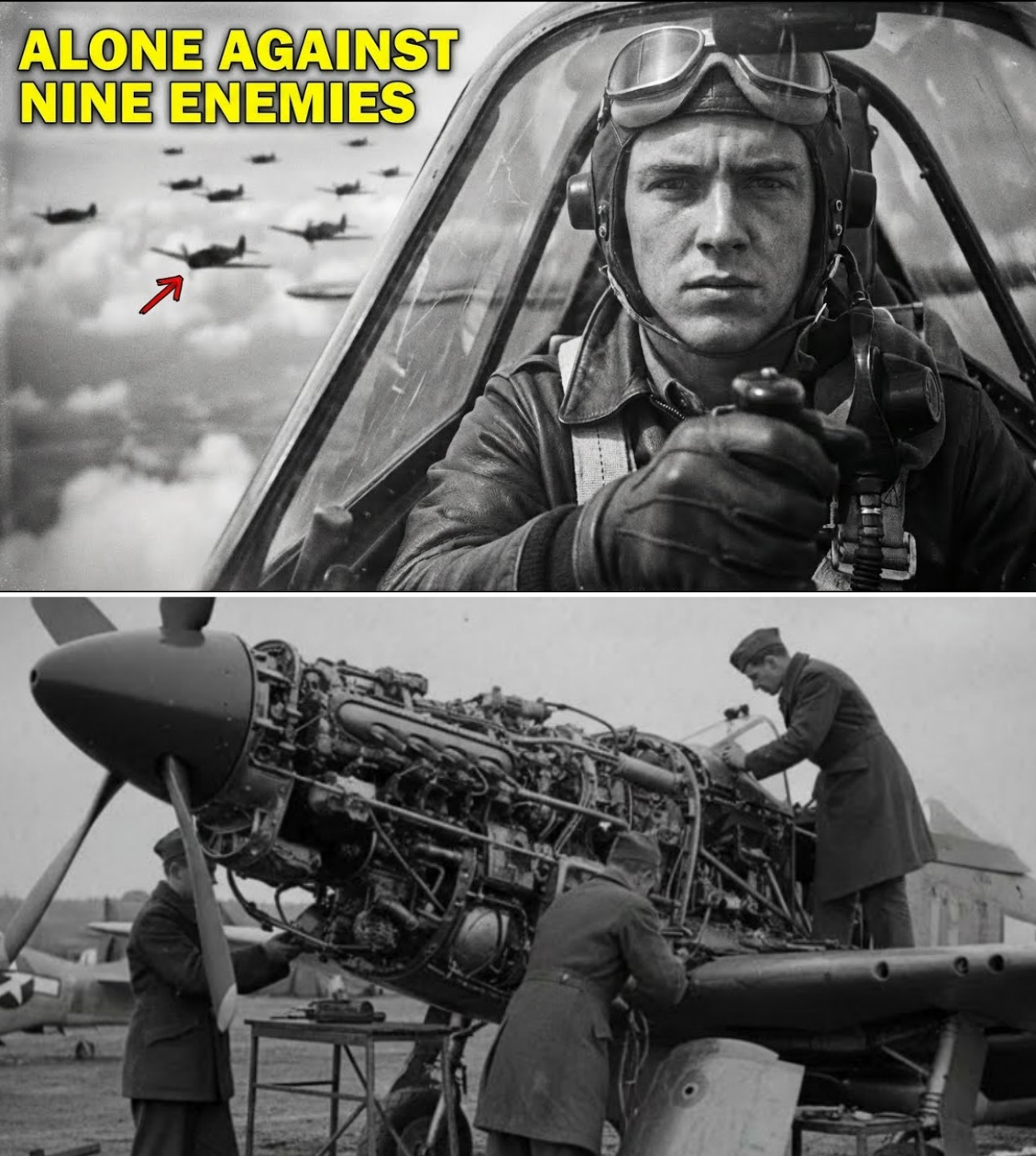

The P-51 Mustang was the best fighter America had, but it could not fly itself. In the hands of a novice, it was just an expensive coffin. Debbdon Airfield sat in the rolling fields of Essex, England, home to the Fourth Fighter Group, formerly the Eagle Squadron, a collection of American volunteers who had fought for the RAF before Pearl Harbor. These men were not fresh.

They had survived the Battle of Britain. They had learned to kill in Spitfires before transitioning to Mustangs. They were hard, seasoned, and skeptical of anyone who had not yet proven himself in combat. The ground crews worked in the cold drizzle, patching holes in aluminum skin, replacing hydraulic lines, scrubbing blood from cockpits.

The smell of argos and cordite hung in the damp air. Engines coughed to life before dawn. Pilots checked their guns, their radios, their oxygen. They did not speak much. There was nothing left to say. Into this world walked Second Lieutenant Charles Mccoral, 19 years old, blonde hair, soft features, a face that still carried the roundness of adolescence.

He had completed advanced training in California, logged his required hours, and been shipped overseas with a dozen other replacements. None of them had ever fired a gun in anger. None had ever seen a German fighter except in grainy film reels. The older pilots glanced at him and looked away.

One muttered something about sending children to do men’s work. Another suggested he might last a week if he was lucky. The squadron operations officer assigned him to a flight, gave him a brief on radio protocols, and told him to stay close to his leader. Mccoral nodded. He did not argue. He knew what they saw when they looked at him, but he had flown since he was 15.

His father owned a small airfield in Pennsylvania. Mccoral had soloed in a Piper Cub before he could legally drive. He understood lift, drag, energy management, and angles. He had spent thousands of hours in the air, most of it alone, learning to read the sky the way some men read books.

He was young, he was untested, but he was not incompetent. The mission briefing came at 0600 hours. Bomber escort, deep penetration into Germany, expected heavy resistance. The intelligence officer pointed to a map covered in red circles, each one representing a known Luftwaffe airfield. The bomber stream would pass near three of them.

The Mustangs would fly top cover, engage any interceptors, and protect the heavies at all costs. Mccoral suited up in silence, parachute harness, May West life vest, leather jacket, gloves. He walked out to his assigned aircraft, a P-51B, with the identification letters QPM. The crew chief, a sergeant from Ohio, gave him a quick rundown of the plane’s quirks.

The throttle stuck a little at high RPM. The radio could be temperamental. The guns were boreed at 300 yd. Mccoral listened, nodded, and climbed into the cockpit. The Merlin engine roared to life. 1,200 horsepower, shaking the airframe. He ran through the checklist, tested the controls, checked the fuel mixture. Around him, 30 other Mustangs were doing the same.

The noise was deafening. The air shimmered with heat and exhaust. They took off in pairs, lifting into the gray English morning. The formation assembled over the channel, a swarm of silver fighters climbing toward the continent. Mccoral flew on the wing of his flight leader, a captain named Donahghue, a veteran with eight kills.

Donahghue’s voice crackled over the radio. Stay tight. Watch your six. Call out any bandits. Mccoral acknowledged. They crossed the coast of France at 18,000 ft. Below the scarred earth of occupied Europe stretched toward the horizon. The bomber stream was visible ahead. A long trail of B17s and B-24s glinting in the cold sunlight. The Mustangs spread out, scanning the sky for threats.

Somewhere over Belgium, Donna [clears throat] Hugh’s engine began to misfire. Smoke trailed from the cowling. He radioed that he was aborting, turning back toward England. He told Mccoral to stay with the group, link up with another flight. But the formation was spread thin. By the time Mccoral tried to join another element, they had already moved ahead.

He was alone. If this history matters to you, tap like and subscribe. Flying alone over enemy territory was a violation of every tactical principle drilled into fighter pilots. The Luftwaffa hunted stragglers. German aces worked in pairs, using altitude and surprise to bounce isolated targets. A lone Mustang, no matter how fast, was vulnerable.

Mccoral knew this, but turning back meant abandoning the bombers. It meant admitting he could not handle the mission. It meant proving the veterans right. So he stayed. He climbed higher up to 25,000 ft where the air was thin and the visibility stretched for miles. He scanned the horizon in quadrants, the [snorts] way his instructors had taught him. Left, right, above, behind, repeat.

The bombers droned on toward their target, a marshalling yard deep in Germany. Flack began to burst around them, black puffs of shrapnel that hung in the air like dirty cotton. The formations tightened. The mustangs wo above and behind, searching for the inevitable attack. It came from the north.

A formation of Faulk Wolf 190s, sleek and deadly, diving out of the sun. They came fast, wings sparkling with cannon fire, tearing into the bomber stream. The radio exploded with chatter. Bandits high. Bandit 6:00. Break left. Two more at 3:00. Mustangs peeled off to engage, twisting into the chaos. Mccoral saw them.

nine FW190s in a loose gaggle, climbing back up after their first pass. They had not seen him. He was above them, positioned perfectly. For a moment, he hesitated. 9 to one. Every instinct told him to call for help, to wait for support. But the bombers were still under attack. Men were dying. He rolled, inverted, and dove. The Mustang accelerated 300 mph, 350, 400.

The air screamed past the canopy. The 190s grew larger in his gunsite. He picked the trailing aircraft, centered the pipper, and squeezed the trigger. The 450 caliber machine guns hammered. Tracers arked through the sky. The first burst missed. He adjusted, fired again. This time the rounds walked up the fuselage of the 190. Pieces flew off.

Smoke poured from the engine. The German fighter rolled over and fell away. The others scattered. They had not expected an attack from above. Mccoral kept his speed, slashing through the formation, firing at another 190 as it broke right. He saw strikes on the wing route, but the German kept flying. No time to confirm.

He pulled hard, blood draining from his head, vision narrowing. The G forces crushed him into the seat. Now they knew he was there. The 190s regrouped, turning toward him. He was no longer the hunter. He counted them. Eight left. They came at him from multiple angles, trying to box him in. He shoved the throttle forward, diving again, using the Mustang’s speed to extend away.

The 190s were faster in a dive, but the P-51 could outturn them at high speed. He knew this from the manual. Now he had to prove it. One of the Germans closed in, firing. Cannon shells streopy. He broke, left hard, hauling the stick into his lap. The Mustang shuddered on the edge of a stall. The 190 overshot unable to match the turn.

Mccoral reversed, rolling right, pulling lead. He fired. The burst hit the cockpit. The 190 nosed down, trailing fire, two down, but the others were converging. He could not fight them all. He climbed using the Mustang’s superior power at altitude. The 190s followed, but they were slower in the climb.

He gained separation, leveled off, checked his fuel. He had burned a third of his load in the dive and the dog fight, enough to get home if he left now. He looked down. The bombers were still there, still under attack. The other mustangs were engaged, scattered across miles of sky. There was no one else to cover this sector. Mccoral turned back toward the fight.

The Luftwaffa pilots were not novices. Many had been fighting since 1940, surviving the battle of Britain, the Eastern Front, the Mediterranean. They knew how to kill. They had shot down Spitfires, hurricanes, P47s. They flew some of the best piston engine fighters ever built. The Faula Wolf 190 was fast, rugged, and heavily armed.

In the hands of an experienced pilot, it was lethal. But experience alone does not guarantee victory. War is not a fair equation. It is a test of adaptability, of split-second decisions, of who can think faster when everything is chaos. The German pilots expected the young American to run.

They expected him to panic, to make a mistake. They had seen it before. Green pilots dove for the deck or climbed too steeply and stalled or froze and died without firing a shot. Mccoral did none of those things. He came back at them from a different angle using the sun to mask his approach. The 190s were climbing, trying to regain altitude advantage.

He caught them in a vulnerable position, noses high, speed low. He fired on the lead aircraft, a long burst that shattered the canopy and killed the pilot. The 190 tumbled, spinning toward the earth. Three down. The others broke formation. Each pilot is fighting individually now. One came at him headon. A classic Luftvafa tactic meant to test the nerve of the enemy. Both fighters closed at a combined speed of over 600 mph.

Mccoral held the trigger down, watching the 190 grow in his windscreen. Tracer fire from both aircraft crossed in the space between them. Neither pilot flinched. At the last instant, the German broke left. Mccoral broke right. They flashed past each other, wing tips separated by less than 20 ft. He pulled around, looking for the next threat.

A 190 was on his tail, closing fast. He pulled into a climbing spiral, forcing the German to follow. The Mustang’s Merlin engine gave him an edge at altitude. The 190 struggled to keep up, losing speed, losing position. Mccoral rolled over the top, reversing the spiral and came down on the Germans tail. He fired.

The 190s right wing disintegrated. The fighter rolled inverted and dove into the clouds. Four down, but the others were learning. They stopped trying to dogfight him and started using hit and run tactics. One would dive in, fire a burst, and zoom away before Mccoral could respond. Another would come from a different angle, forcing him to choose which threat to counter.

It was classic fighter doctrine, divide and conquer. Mccoral did not try to chase them. Instead, he stayed near the bombers, using them as bait. The one90s had a mission. They had been ordered to attack the bombers, not to waste fuel dog fighting with escorts. Eventually, they had to commit. When they did, he was waiting.

A 190 dove toward a straggling B17, lining up for a gun run. Mccoral cut him off, firing from a 30° deflection angle. It was a difficult shot, requiring him to lead the target to calculate the 190s speed and trajectory in a fraction of a second. The burst hit the engine. The 190 pulled up, trailing smoke, and broke away. Mccoral followed, firing again.

This time the German pilot bailed out, his parachutes snapping open as the 190 spiraled down. Five down. The remaining three 190s regrouped and broke off the attack. They had lost more than half their number. The bombers were past the target, turning for home. There was no point in continuing. They dove away, heading back to their airfield.

Mccoral let them go. His ammunition was nearly gone. His fuel gauge showed less than a quarter tank. He was 200 m inside Germany alone with no wingman and no idea if the other Mustangs had made it through the fight. He turned west and began the long flight home. The return flight was a study in isolation. The sky, so full of violence minutes before, was now empty.

The bomber stream had already passed ahead, escorted by other fighters. Mccoral flew alone, listening to the steady roar of the Merlin engine, watching the fuel gauge drop. He descended to 15,000 ft to conserve fuel. Below the German countryside unfolded in shades of gray and brown, rivers, towns, railways. He saw no other aircraft.

The radio crackled occasionally with distant chatter, but no one called his name. For all he knew, he was the only one left. Crossing back into Allied airspace over France, he finally heard a familiar voice. Donahghue, his flight leader, had made it back to England and was coordinating the return of the scattered group.

Mccoral keyed his radio and reported his position. Donahghue asked if he was damaged. Mccoral said no. Donahghue asked how many bandits he had engaged. Mccoral hesitated. then told him nine. There was silence on the radio. Then Donahghue asked how many he had claimed. Mccoral said he thought five, maybe four, confirmed. Donahghue told him to get his ass back to Debbon and to land before he ran out of gas.

Mccoral crossed the English coast with the fuel warning light glowing red. He descended through a layer of clouds and found the airfield, the runway, wet and dark in the afternoon gloom. He lowered the landing gear, dropped the flaps, and brought the Mustang in. The wheels touched down smoothly.

He taxied to the hard stand, shut down the engine, and climbed out. The crew chief was waiting. He walked around the aircraft, examining the skin. No bullet holes, no damage. He looked at Mccoral and asked if he had seen any action. Mccoral said he had. The crew chief counted the empty shell casings scattered inside the gun bays.

Over a thousand rounds expended. He whistled. The intelligence officer debriefed him in a small office smelling of coffee and cigarette smoke. Mccoral described the engagement, the number of enemy aircraft, the altitude, the times, the results. The officer took notes, asked clarifying questions, and told him they would review the gun camera footage.

Mccoral had forgotten about the camera. Every burst he fired had been recorded. That evening, the footage was developed and screened. The squadron gathered in the briefing room, pilots and ground crew crowding around the projector. The film showed everything. The first 190 breaking apart under fire. The second diving away, trailing smoke.

The third tumbling out of control. The fourth losing a wing. The fifth pilot bailing out. The room was silent. When the film ended, someone began to clap. Then others joined. The squadron commander stood and shook Mccoral’s hand. Donaghue, the flight leader who had aborted with engine trouble, put a hand on his shoulder and said he was glad to have him on the wing.

Mccoral did not smile. He did not feel like celebrating. He had just killed five men, maybe more. He had watched them fall, watched their aircraft disintegrate, watched a parachute open, and a man drift down toward a land that was no longer his. It was not glorious. It was not clean. It was simply what he had been sent to do.

But it was also proof. Proof that youth was not the same as incompetence. Proof that a fresh pilot, if he kept his head, if he used logic and training and instinct, could survive and even prevail against veterans. The squadron no longer saw him as a child. They saw him as one of them. The air war over Europe in 1944 was reaching a crescendo.

The Allied invasion of Normandy was weeks away. The eighth air force was systematically destroying German industry, transportation, and fuel supplies. The Luftvafa, once the most feared air force in the world, was being ground down by attrition. Every day, experienced German pilots were killed or captured. Every day their replacements were younger, less trained, more desperate, but the fighting was still brutal.

The Luftvafa still had teeth. Messmid 109s and Faulolf 190s still rose to meet the bombers, and men still died at altitude. Mccoral flew mission after mission. He learned the rhythms of combat, the way a dog fight unfolded, the way a pilot’s instincts could be sharper than his thoughts. He learned to trust his hands to let muscle memory take over when there was no time to think.

He shot down more aircraft. By the end of April, he had nine confirmed kills. By June, he was an ace. He was still 19. Other pilots began to ask him for advice. How did he see the enemy before they saw him? How did he judge deflection on a crossing shot? How did he stay calm when outnumbered? Mccoral struggled to explain.

It was not something he had been taught. It was instinct honed by hours in the air by a childhood spent flying alone over Pennsylvania fields by a mind that processed angles and speeds without conscious thought. But there was something else. A quality that could not be trained or measured. A kind of cold clarity that descended when the bullets started flying.

Most pilots felt fear. Mccoral felt focus. The world slowed down. Decisions became obvious. He did not hesitate. He did not second guesses. He simply acted. The eighth air force took notice. Mccoral was promoted to first lieutenant. He was given command of his own flight. He was interviewed by war correspondents, his boyish face appearing in newspapers back home.

The headline read, “Teen ace defies odds over Germany.” His mother sent him the clipping in a letter. She said she was proud. She also said she prayed every night for him to come home. He wrote back. He told her he was fine. He did not tell her about the nightmares, the faces of the German pilots he had killed, the sound of a Mustang breaking apart, the cold silence of the radio when someone did not check in.

He did not tell her that he had stopped counting the missions, that he had stopped thinking about the future, that he lived daytoday, flight to flight, because anything else was unbearable. In late June, Mccoral’s squadron was assigned to ground attack missions. The invasion had begun. The Allies were pushing inland from the beaches, but German armored divisions were counterattacking.

The Mustangs were tasked with strafing enemy columns, destroying trucks, tanks, and rail cars. It was dangerous work. Flack was heavier at low altitude. A single burst could bring down a fighter. Mccoral flew these missions with the same cold precision he brought to air combat. He would dive on a target, fire, and pull up through the flack, the Mustang shaking from near misses.

On one mission, a shell fragment tore through his right wing, punching a hole the size of a basketball. He made it back to base. The crew chief shook his head and said the wing spar was cracked. The plane was grounded for a week. Mccoral flew a different aircraft the next day. By August, the Luftwaffer was in retreat.

The skies over France were largely clear. The bombers flew deeper into Germany with fewer losses. The Mustangs ranged ahead, shooting up anything that moved. The war was not over, but the outcome was no longer in doubt. Mccoral’s final tally was 21 confirmed kills with several more probables. He flew over a 100 combat missions.

He was awarded theDistinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal with multiple Oak Leaf Clusters. He was 20 years old. The end of the war in Europe came in May 1945. Mccoral was still in England when the news broke. The squadron gathered in the mesh hall, drinking and shouting, some men crying. The war was over. They had survived, but the celebration felt hollow. So many had not made it.

Empty bunks, missing faces, names scratched off the duty roster. The cost had been staggering. The Eighth Air Force alone had lost over 26,000 men, pilots, gunners, bombarders, navigators, boys who had left farms and factories and colleges and never came home. Mccoral sat alone in the corner of the room, nursing a glass of whiskey he did not drink.

He thought about the first mission, the nine FW190s, the moment he had decided to stay and fight. He thought about the men he had killed, the ones whose faces he had seen in the gun camera footage, the ones who had died because he had been faster, luckier, better. He wondered if they had families. He wondered if they had been mocked for being too young, too inexperienced, too soft.

He wondered if they had been like him. The Air Force offered him a post-war career. They wanted to keep him to train the next generation of pilots. Mccoral declined. He went home to Pennsylvania. He enrolled in college. He tried to live a normal life, but he never stopped flying. He bought a small plane, a Piper Cub like the one he had learned in.

He flew alone over the same fields he had flown as a boy before the war, before the killing. The sky was the only place where he felt calm, the only place where the memories did not follow. In the decades that followed, Mccoral rarely spoke about the war. He did not attend reunions. He did not give interviews.

When people learned he had been an ace, they asked him what it was like, how it felt to be a hero. He told them it was not like anything. It was a job. He did it because it needed to be done. But once late in his life, a young pilot approached him at an air show. The pilot was about to deploy overseas and he was nervous. He asked Mccoral for advice.

Mccoral looked at him. this kid with a fresh uniform and uncertain eyes. And he saw himself at 19 standing on the tarmac at Debbon, surrounded by men who did not believe in him. He told the young pilot to trust himself, to remember his training, to stay calm when everything around him was chaos, and if he found himself alone, outnumbered, with no one to help, to remember that fear and competence were not the same thing.

that being young did not mean being weak. That courage was not the absence of fear, but the decision to act in spite of it. The young pilot thanked him and walked away. Mccoral watched him go, wondering if he would make it, if he would survive whatever war awaited him. He hoped he would. He hoped that the lessons paid for in blood over Germany would not be forgotten.

Charles Mccoral died in 2003 at the age of 78. His obituary mentioned his service, his medals, his record as an ace. It did not mention the nightmares, the weight he carried, the faces that never left him. It did not mention that he had been 19 when he fought nine enemy fighters alone and lived to tell about it. But the story survived.

It was passed down among pilots, told in ready rooms and hanger bars, a reminder that youth is not weakness, that skill is not the same as age, that sometimes the most dangerous pilot in the sky is the one no one expects. The Mustang he flew that day, QPM, was scrapped after the war. The gun camera footage is archived, a silent black and white film of a young man doing what needed to be done.

The official records list his kills, his missions, his awards, but the numbers do not capture what happened that March morning in 1944 when a teenager with a baby face and a sharp mind climbed into a fighter and proved that courage and competence have no age limit. War is not fair. It does not care about experience or seniority.

It only cares about who can think faster, shoot straighter, and survive longer. Mccoral survived because he understood that. He survived because he did not let fear or doubt cloud his judgment. He survived because when everyone else saw a child, he saw a pilot. The lesson is not that youth should be sent to war.

The lesson is that when war comes, those who fight it should be judged by their actions, not their appearance. That leadership and courage can emerge from unexpected places. That the quiet kid in the corner, the one no one takes seriously, might be the one who changes everything. Mccoral never wanted to be a hero. He wanted to fly.

The war took that from him, turned it into something darker, something stained with violence and loss. But it also revealed something essential. That in the crucible of combat, character is tested in ways that peacetime never demands. That some people, when everything is on the line, rise to the moment, not because they are special, but because they refuse to quit. The sky over Debbon is quiet now.

The airfield is gone, returned to farmland. The men who flew from there are almost all gone, too. Their stories are fading with them. But the lesson remains, etched into history by the actions of one young pilot on one impossible day. They mocked him for being too young. He proved them wrong at 25,000 ft alone against nine with nothing but skill and will and a P-51 that answered to his hands.

And when the smoke cleared and the film was developed and the truth was undeniable, no one ever questioned him again. That is not just a war story. It is a reminder that the future belongs to those brave enough to seize it. That competence speaks louder than age. That sometimes the most dangerous thing you can do is underestimate the quiet ones who refuse to back down.

Charles Mccoral flew into history on his first day of combat. But he earned his place there one decision at a time. One burst of gunfire, one impossible turn, one refusal to quit when quitting was the logical choice. And in doing so, he left a legacy that transcends medals and records and fading photographs.

He left proof that courage is not inherited or awarded. It is chosen in the moment when no one is watching and the odds are impossible. And that choice made at 19 over the skies of Germany echoes.