“Eat This Brown Paste” – German Women POWs Shocked That Americans Ate Peanut Butter Every Day

In November 1944, 34 German women prisoners of war arrived at Camp Aliceville, Alabama, expecting the worst. They had been captured as part of the German Women’s Auxiliary Corps, tasked with supporting the Nazi war effort in ways that didn’t require pulling triggers—nurses, signal operators, secretaries. But nothing, absolutely nothing, could have prepared them for what they were about to experience in the heart of rural America.

For years, these women had been taught to fear the United States, to believe that their enemy was weak and starving. Nazi propaganda had painted a bleak picture of America: a country on the verge of collapse, plagued by poverty, with its citizens lining up for food while the Jewish elite controlled everything from behind the scenes. But as they stepped off the train and into the humid Alabama air, they found themselves at the mercy of a very different reality.

The camp was clean and functional, far from the horrors they had imagined. Barbed wire fences, yes, but they weren’t confined to the same dilapidated conditions they had expected. The women were housed in wooden barracks with real beds, hot water in the showers, and a medical clinic. It was a far cry from the horrors they had been warned about. They had been captured by their supposed enemies, but in this strange land, the lines between captor and captive began to blur.

The first meal at Camp Aliceville confirmed their suspicions—this was not the suffering they had been promised. They were given bread, meat, canned peaches in syrup, and a strange nutty smell wafted from the tables. In the center of each one sat a glass jar filled with a brown paste. None of them knew what it was, but they knew it didn’t look like food. It resembled axle grease or something that belonged in a mechanic’s workshop, not a dining hall.

Helga Brandt, a 26-year-old nurse from Raml’s Africa Corps, stared at the jar with confusion. Her mind raced—this couldn’t be food. But then, to her disbelief, one of the American guards, a young woman in a kitchen apron, scooped the mysterious brown paste straight from the jar with a spoon. No bread. No shame. She smiled and said, “Best thing in the world. You’ll love it.”

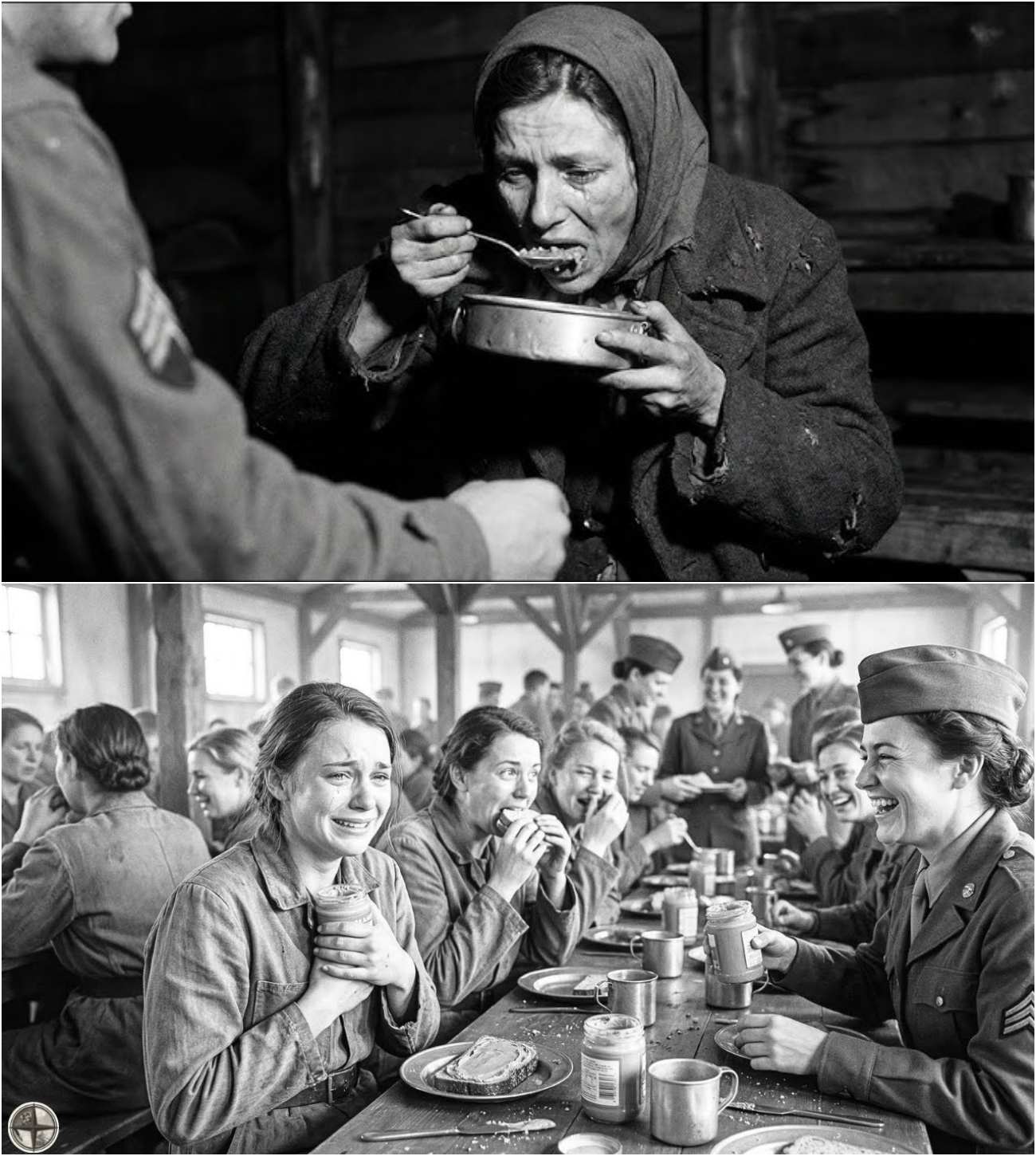

The German women exchanged looks. Some laughed nervously. They assumed this was some kind of cruel joke—a way to mock their helplessness. But what they saw next shattered their assumptions. The American guards, soldiers, and kitchen staff were eating the same thing. They weren’t offered different food; they were eating the exact same meals. No special treatment, no extra portions for the guards. Everyone ate the same food, including the strange brown paste.

Helga’s blood ran cold. Everything she had been told about America was a lie. Propaganda films had shown the American people starving, standing in breadlines, fighting to survive. They were supposed to be weak. How could a starving nation afford peanut butter, let alone eat it like it was a treat? Helga’s mind raced as the enormity of what she had been taught—and what she was now seeing—began to collide.

By the next meal, Helga and the other women had taken matters into their own hands. They could no longer resist the strange allure of the peanut butter. Ingrid, a fellow prisoner, was the first to try it. She opened a jar and spread a thin layer of the brown paste on bread. She took a tentative bite. The others watched in complete silence, holding their breath, waiting for her reaction.

Ingrid’s face lit up. “It’s… good,” she whispered. “It’s salty and sweet at the same time. It’s like… energy. Like strength.” The other women were still hesitant, unsure whether to believe it, but one by one, they reached for the jars. The transformation was immediate. They had been starving, surviving on the bare minimum for years. Now, they were consuming something rich, filling, and strangely comforting.

Within minutes, the entire table was emptying jar after jar of peanut butter. The American kitchen staff watched in bewilderment as 47 jars of peanut butter were consumed in a single breakfast. The women had gone from refusing to touch it, to devouring it with an urgency that bordered on desperation.

For the first time, Helga and her fellow prisoners began to understand the concept of abundance. Peanut butter, a simple food made from peanuts, became their currency. By the second week, a black market economy had emerged in Camp Aliceville, and peanut butter was the most coveted commodity. Women traded their precious items—silver earrings, wedding rings, even their clothing—for a spoonful of the brown paste. It became more valuable than cigarettes, more precious than gold.

This newfound obsession with peanut butter wasn’t just about food. It was about the undeniable truth that America was not the starving, broken nation they had been led to believe. The contrast between the realities of life in America and the lies of Nazi propaganda had become too vast to ignore. The women who had once believed that they were fighting for a righteous cause, now saw their world crumble as they realized that the very foundation of their beliefs had been built on lies.

Helga, who had been raised on Nazi ideals, couldn’t ignore the realization that everything she had been taught was false. America was not the weak, starving nation she had been told about. It was a country overflowing with abundance, a place where soldiers shared the same food as their prisoners. They had given these women more than just food. They had given them a glimpse into a world of equality and decency, a world that Helga had never imagined.

The impact of this realization was profound. It was more than just food—it was a crack in the wall of Nazi ideology. For the first time, the women of Camp Aliceville began to question everything they had been taught. The peanut butter was a gateway to understanding the truth. They had been lied to for years, fed propaganda that painted the world in black and white. But now, they saw that the world was far more complex than they had ever imagined.

By the end of 1944, as the war was turning against Germany, the prisoners in Camp Aliceville had begun to change. The peanut butter had become a symbol of transformation. It wasn’t just about food anymore; it was about discovering the power of truth over propaganda. These women, who had once believed they were fighting for a superior nation, now saw their own government’s lies for what they were.

The transformation didn’t stop there. By the time the women were repatriated to Germany in 1947, they had become different people. The lessons they had learned in Alabama—about kindness, abundance, and the reality of life in America—were more powerful than anything they had experienced in battle. They returned to a broken Germany, one that had been devastated by war, and they carried with them a new understanding of the world.

Helga, years later, would recall those moments in the mess hall, where the simple act of sharing a meal with their captors had changed everything. “We learned that the world is not what we were told. We learned that truth is not something you can take for granted. It is something you discover, often in the most unexpected places.”

And for 34 German women, that discovery began with a jar of peanut butter. What started as a simple meal turned into the most powerful weapon in the war for truth. A weapon that didn’t fire bullets or drop bombs, but one that shattered the lies of Nazi propaganda, one spoonful at a time. The women left Camp Aliceville with more than just memories of a strange food; they left with the truth that would haunt them forever.

America, with its peanut butter, had shown them something more powerful than any victory on the battlefield. It had shown them humanity, and that was the most dangerous weapon of all.