German Child Soldiers Refused to Eat Thanksgiving Dinner — Until the Cook Told Them What It Meant

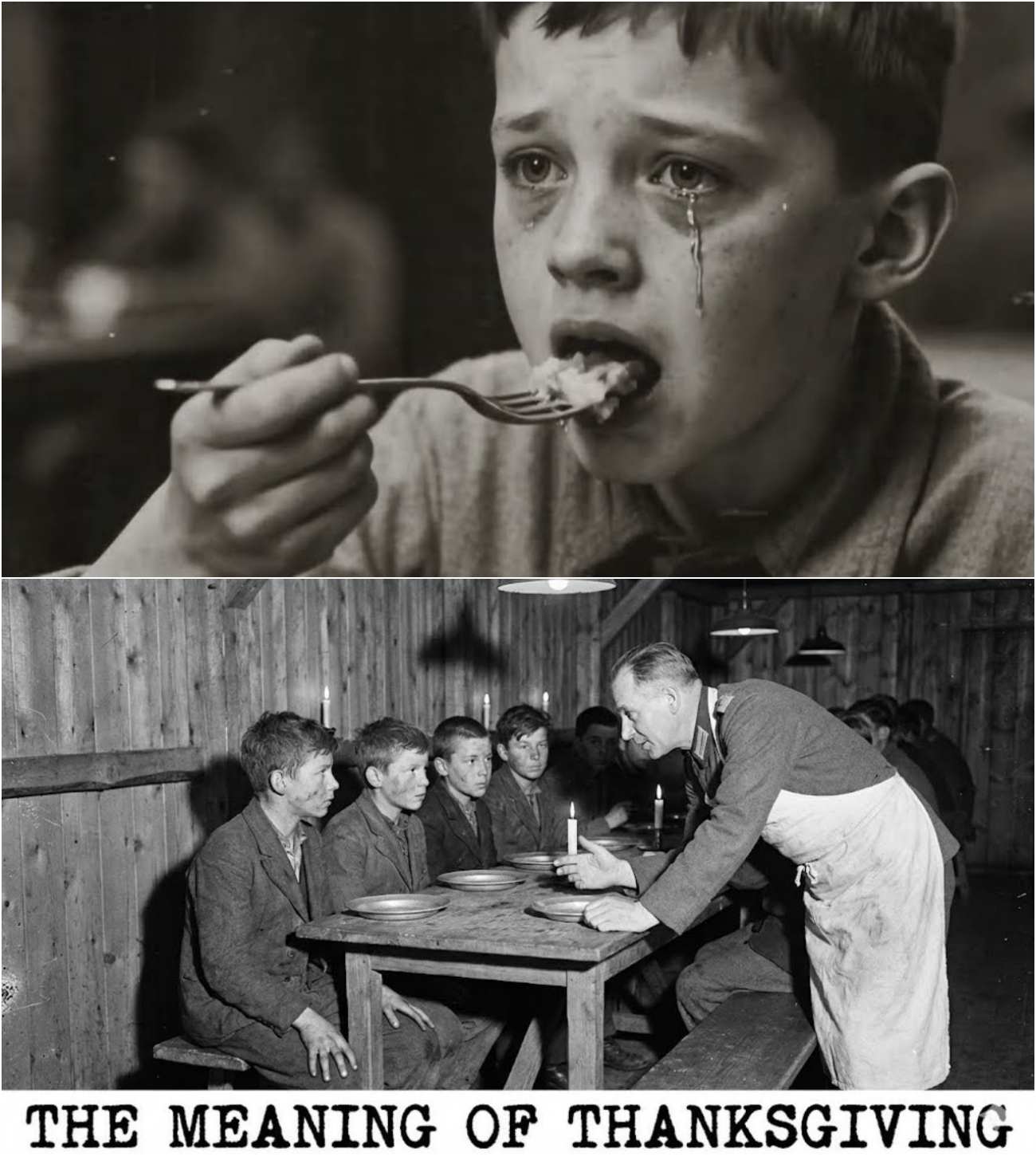

On November 23, 1944, a seemingly ordinary Thanksgiving morning unfolded at Camp Campbell, Kentucky. The air was filled with the mouthwatering aroma of roasted turkey, mashed potatoes, and cranberry sauce. Yet, at one corner table, twelve boys in grey wool shirts sat with their arms crossed, their plates untouched. Their eyes were fixed on the floor, a stark contrast to the joyous atmosphere around them. These were not just any boys; they were German soldiers, aged between 14 and 17, who had been prisoners of war for just three weeks.

The Weight of Ideology

These young men had entered the camp with their spirits unbroken, despite their physical frailty. They had been part of the Hitler Youth, indoctrinated from a young age with lessons of loyalty, sacrifice, and the belief that surrender was the ultimate betrayal. Now, as they sat in silence, they were grappling with a profound internal conflict. The Thanksgiving feast laid before them felt like a trap, an act of propaganda from their captors. They had been taught that kindness was a guise for weakness, something to be exploited.

While older prisoners—battle-hardened veterans—accepted their meals without hesitation, these boys remained resolute in their refusal. To them, the food represented not a gesture of humanity, but a reminder of their defeat. They were caught in a web of ideology, suspicion, and an unwillingness to accept the kindness of their enemies.

The Cook’s Compassion

Amidst this tension, the camp cook, Robert Dunn, observed the boys from the kitchen. A veteran of the First World War, Dunn understood the power of food beyond mere sustenance; it was a symbol of memory and home. He had witnessed the depths of despair in soldiers and prisoners alike, and he recognized the fear and defiance in the boys’ eyes.

Dunn decided to intervene, not with punishment or reprimand, but with a story. He approached the boys, carrying only his age and a soft Kentucky drawl, and sat down at their table. He began speaking in broken German, asking if they understood English. With a nod from Klaus, the tallest among them, Dunn switched to English and shared a tale that would change everything.

A Story of Survival

He spoke of a group of people who had crossed an ocean—not as conquerors, but as refugees fleeing persecution. They arrived in a new land, unprepared for survival, and faced a harsh winter where many perished. Yet, amidst their suffering, they encountered strangers who offered them help not out of obligation, but out of compassion. These strangers taught the refugees how to plant crops, fish, and survive the seasons.

As the harvest came, the refugees held a feast—not to celebrate victory, but to express gratitude for their survival and the kindness they had received. Dunn leaned in closer, emphasizing that Thanksgiving was not about American dominance over Germany, but about the simple act of strangers feeding one another. It was about recognizing that survival was a shared experience, transcending borders and ideologies.

The Shift in Perspective

As Dunn finished his story, a profound silence enveloped the mess hall. The boys sat in contemplation, the weight of Dunn’s words settling heavily upon them. Klaus, breaking the stillness, picked up his fork and quietly translated for the others. He articulated the transformation happening within them: they weren’t refusing to eat because they were Americans; they were refusing because they were still alive, and being alive held significance.

One by one, the boys began to reach for their forks. They ate slowly, cautiously, as if each bite required permission. The guards and older prisoners watched in silence, witnessing a moment of profound change. The act of eating was no longer an act of submission; it became a recognition of their humanity, a realization that they were not merely soldiers but survivors.

A New Identity

As they consumed their meal, the boys began to shed the armor of ideology that had defined them for so long. They had been taught that the world was divided into the strong and the weak, the victors and the defeated. But Dunn’s story had introduced a new category: the saved. They were not just defeated soldiers; they were refugees, having fled a burning country and survived battles they had not chosen.

After the meal, they returned to their barracks, but something had shifted. They began to engage with the older prisoners, asking questions not about the war, but about life before it. They were curious about farms, families, and what it was like to live without fear. The older men responded with kindness, sharing their truths without judgment, helping the boys remember their lost childhoods.

The Legacy of a Simple Meal

Robert Dunn never sought recognition for his actions that day; he simply returned to the kitchen, continuing to cook for the soldiers and prisoners. Yet, the story of that Thanksgiving spread throughout the camp. Years later, some of those boys returned to Germany, carrying the memory of that transformative meal with them. Klaus, in particular, wrote a letter in 1953, addressed to Camp Campbell and forwarded to Dunn’s diner in Clarksville. In it, he expressed how the meal had saved more than just his body; it had saved a part of his spirit.

The boys scattered after the war, some returning to cities in ruins, others immigrating to South America, and some remaining in the United States. But they all carried the same memory of that day, a moment when they ceased to be soldiers and embraced their identities as survivors.

Reflection on Humanity

Thanksgiving 1944 at Camp Campbell was not marked by grand celebrations; there were no speeches or medals. It was a simple act of humanity—a cook and twelve boys sharing a meal. Yet, it became a powerful reminder that even the smallest acts of kindness can alter the trajectory of a life.

The boys had been taught that surrender was weakness and that mercy was manipulation. But Robert Dunn had shown them otherwise. He demonstrated that history is filled with stories of people saved by strangers, and that being saved does not signify weakness—it signifies humanity.

As the war continued for another six months, claiming millions more lives and redrawing borders, the boys learned that gratitude transcends politics. It is about recognizing the shared experience of survival, and sometimes, the people who feed you are the ones who teach you how to live.

In the years that followed, as the mess hall faded into memory and Camp Campbell transformed into Fort Campbell, the essence of that day endured. The long wooden tables where they once sat shoulder to shoulder may no longer exist, but the lessons learned that day remain etched in the hearts of those who experienced it.

The True Meaning of Thanksgiving

The truth that emerged from that meal was profound: sometimes, the most powerful weapon is not a gun, but a meal. The greatest victory is not conquest, but the choice to sit down and eat with your enemy, to share bread and acknowledge each other’s humanity.

For those twelve boys, the Thanksgiving meal was not just a holiday; it became a truth that resonated long after the war had ended. They learned to embrace their humanity amidst the chaos of conflict, recognizing that survival, gratitude, and connection are what truly matter in the face of adversity.

In a world often defined by division, the story of Robert Dunn and the German child soldiers serves as a poignant reminder of the power of compassion and the enduring impact of simple acts of kindness. It is a testament to the idea that even in the darkest times, humanity can shine through, bridging divides and fostering understanding where once there was only enmity.