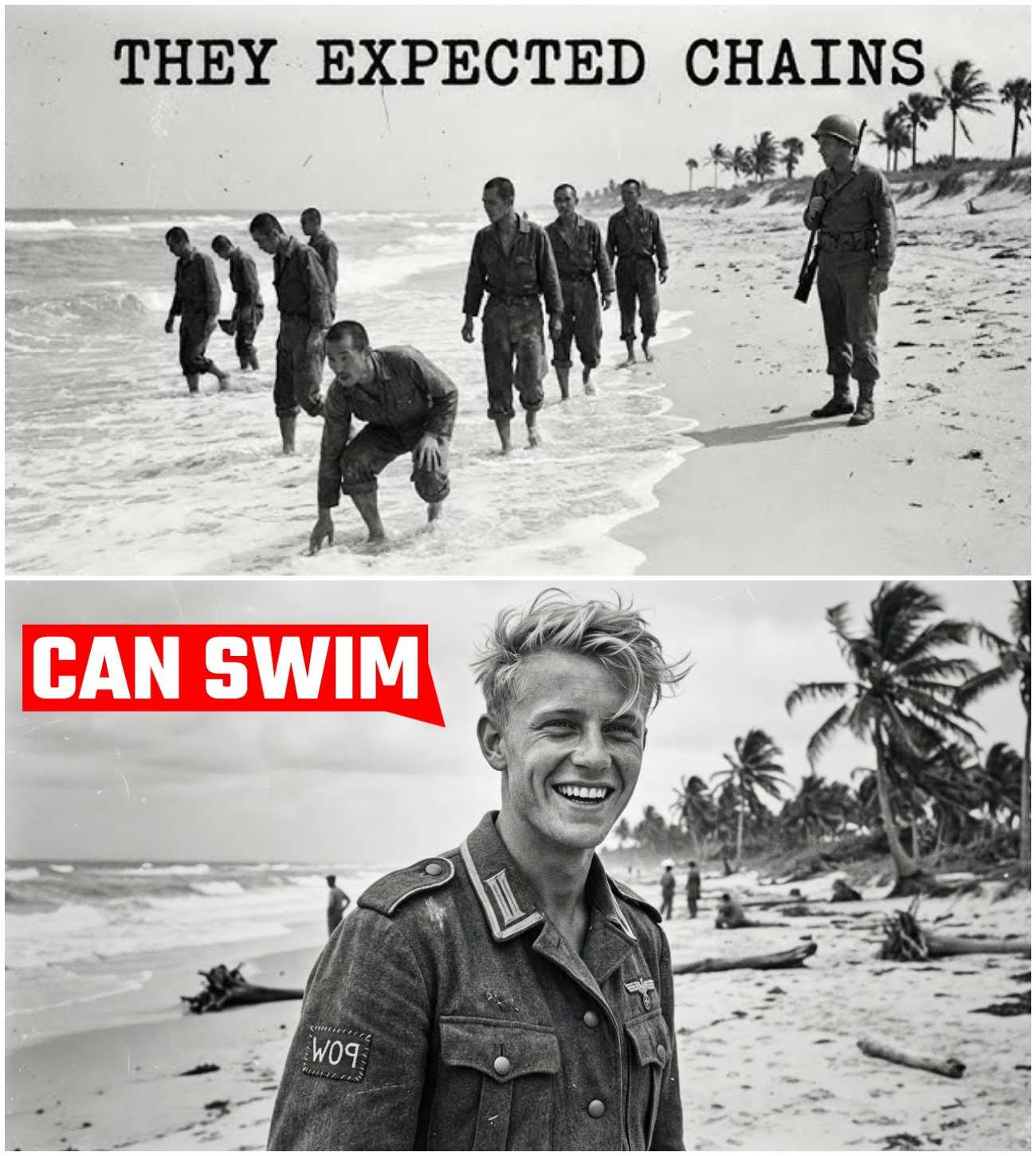

German POWs in Florida Were Taken to the Beach – They Were Shocked Americans Just Let Them Swim

In the summer of 1943, as the world was engulfed in the turmoil of World War II, a remarkable story of compassion and humanity unfolded on the shores of Lake Geneva in Florida. This is the story of Oberleutnant Klaus Weber, a German soldier captured in North Africa, who found himself in an American POW camp where he experienced moments of unexpected kindness that would forever change his perspective on the war and his captors.

Captured and Transported

On June 18, 1943, at 2:47 PM, Klaus Weber sat in the back of an American army truck, watching palm trees pass by through the canvas opening. At just 24 years old, he had been captured three weeks earlier in Tunisia and was now being transported across the Atlantic on a Liberty ship. As he sat with 11 other German prisoners, he struggled to comprehend what was happening. The guards had informed them they were heading to a place called Lake Geneva, but to Weber, swimming during wartime felt absurd.

Weber had surrendered to British forces on May 12, after his unit, the 21st Panzer Division, was surrounded with no food or ammunition. Following his capture, he spent nine days in a collection point, where he witnessed thousands of German and Italian soldiers waiting for transport. The journey to America took 17 days, and conditions were cramped and uncomfortable, with seasickness and the constant fear of being torpedoed.

Upon arriving at Camp Blanding in Florida on June 11, Weber was processed as a POW. He was photographed, fingerprinted, and issued a clean uniform—American field jackets dyed with “PW” markings on the back. The barracks were wooden structures with screened windows, and the camp offered amenities he had never expected. The food was plentiful, with hot meals served three times a day. For the first time in months, Weber felt nourished, enjoying beef stew and real coffee.

Life at Camp Blanding

Weber quickly learned that the United States was adhering to the Geneva Convention, which mandated humane treatment for POWs. The prisoners would work, but they would receive adequate food, medical care, and a daily wage of 80 cents in camp script. This was a far cry from the dark cells and starvation rations he had anticipated based on propaganda films.

On June 14, Weber and 50 other prisoners were assigned to work in the nearby citrus groves. The foreman, an American civilian named Patterson, explained their tasks: each prisoner would fill 30 boxes with oranges, with a break for lunch. The work was physically demanding but straightforward, and Weber quickly adapted to the rhythm of picking fruit under the Florida sun.

During lunch breaks, the prisoners enjoyed sandwiches and as many oranges as they wanted. It was during one of these breaks that Weber struck up a conversation with an American guard named Kowalski. They exchanged small talk, and Weber found it hard to reconcile this friendly interaction with the image he had of Americans as cruel and dishonorable. Kowalski was just a man from Pennsylvania, missing his family and hoping for the war to end.

The Swimming Trip

As the summer progressed, the routine at Camp Blanding included opportunities for recreation. One day, Weber learned that on weekends, prisoners could swim at Lake Geneva. Initially skeptical, he soon found himself volunteering for a swimming trip announced by an American sergeant named Daniels. The idea of swimming in a lake while being a POW seemed absurd, but he was eager to see if it was true.

On June 19, 1943, Weber and 11 other prisoners piled into the back of a truck, excitement bubbling as they drove to the lake. When they arrived, the sight was breathtaking: clear water with a sandy bottom, surrounded by pine trees. The guards, rifles slung over their shoulders, informed the prisoners they could swim in their clothes or underwear. Most opted to strip down, and Weber, feeling the warmth of the sun, decided to keep his pants on but removed his shirt.

As he waded into the water, he was overwhelmed by the sensation of weightlessness and the refreshing coolness. He swam underwater, savoring the silence and joy of the moment. Laughter erupted among the other prisoners, a sound Weber had not heard in a long time. It was a stark contrast to the grim reality of war, and he realized he had forgotten how to laugh.

Shared Humanity

The American guards watched from the shore, laughing and chatting among themselves. In a surreal twist, one of the guards, Matthews, even joined the prisoners in the water, swimming alongside them. This was not how wars were supposed to be; enemies were not meant to share moments of joy and recreation. Yet here they were, all together, enjoying a brief respite from the horrors of conflict.

As Weber floated on his back, he gazed at the clear Florida sky, reflecting on his journey. He thought about his enlistment in the Wehrmacht in 1940, his training, and the relentless fighting in North Africa. Now, he was swimming freely, surrounded by American guards who treated him with a level of dignity he had not expected.

When the time came to return to camp, Weber felt a mix of emotions. The experience had been surreal, and he struggled to articulate it to his fellow prisoners. That night, back in the barracks, he wrote a letter to his mother in Munich, carefully avoiding military details due to censorship. He mentioned his safety and how the Americans treated him well, but he knew she would find it hard to believe that he had gone swimming.

The Changing Atmosphere

As summer turned to fall, the swimming trips continued, but the atmosphere at Camp Blanding began to shift. The weather turned cooler, and the guards announced that swimming was no longer permitted. Instead, the camp organized other recreational activities, such as soccer games and chess tournaments. The lightheartedness of the early summer was replaced by a more serious tone.

In May 1945, Germany surrendered, and the camp administration reduced the prisoners’ rations in response to public outrage over the conditions in German concentration camps. Colonel Hayes addressed the prisoners, explaining the new orders from Washington. While the prisoners accepted the changes without protest, Weber found it difficult to reconcile the reality of the camps with the horror of what was happening in Germany.

Weber had heard rumors during his service about camps in Poland, but he had dismissed them as propaganda. Now, faced with the undeniable truth of the Holocaust, he grappled with feelings of complicity. He had worn the uniform and served the regime, and he struggled to come to terms with the atrocities committed in the name of Germany.

A New Normal

Despite the changes in rations and the atmosphere, life continued at Camp Blanding. Weber worked hard in the citrus groves and later in a Minute Maid processing plant, learning new skills and earning camp script to spend at the canteen. He saved money and enjoyed small luxuries, like candy bars and the occasional Coca-Cola, which he found tasted strange.

As the war continued, Weber remained focused on survival. He picked oranges, attended recreational activities, and waited for the war to end. The prisoners had formed a community, and while they were still confined, they found ways to support one another and create a semblance of normalcy.

By the time he was repatriated in March 1946, Weber had gained weight and improved his health. He boarded a Liberty ship bound for France, reflecting on his experiences in America. He returned to a devastated Germany, where he found his mother living in a basement apartment, struggling to survive in the ruins of their old neighborhood.

A Life Rebuilt

Weber’s time in Florida had changed him. He had learned that even in captivity, humanity could prevail. The kindness shown to him by American guards during those swimming trips reminded him that dignity and compassion could exist even in the darkest circumstances.

Back in Munich, he worked hard to rebuild his life, taking on odd jobs and using the skills he had learned in America. He never spoke about his time as a POW, but the memories of swimming in Lake Geneva and the laughter shared with his fellow prisoners and their guards stayed with him.

Years later, Weber kept a faded photograph taken at Lake Geneva, showing him and the other prisoners smiling on the sandy shore. It was a reminder of a moment of humanity amid the chaos of war. After his death in 1987, his children found the photograph and learned about their father’s time as a prisoner in America—a story of unexpected kindness that contrasted sharply with the horrors of the war.

Conclusion: The Power of Humanity

Klaus Weber’s story is a powerful reminder of the complexities of war and the resilience of the human spirit. It illustrates that even in the darkest times, moments of compassion and understanding can emerge, bridging divides and fostering connections between enemies. The swimming trips at Lake Geneva were not just a diversion for the POWs; they were a testament to the possibility of humanity surviving even in the most challenging circumstances.

As we reflect on this story, we are reminded that kindness knows no borders, and that even in the midst of conflict, we can choose to preserve our humanity. The photograph of Weber and his fellow prisoners serves as a symbol of hope, a reminder that even enemies can find common ground and share moments of joy, laughter, and dignity.