Germans Couldn’t Stop This B-17’s “Secret” Weapon — Until He Destroyed All 17 Planes

March 25, 1945. The Vosges Mountains in eastern France were shrouded in a gray dawn as the sun began to rise, casting a cold light over the remnants of war. Staff Sergeant Michael Aruth crawled into the tail position of B-17 Tandleo at RAF Kimbolton, preparing for a mission that would take him deep into enemy territory—500 miles into Germany. At just 24 years old, he had already completed 12 combat missions and had three confirmed kills.

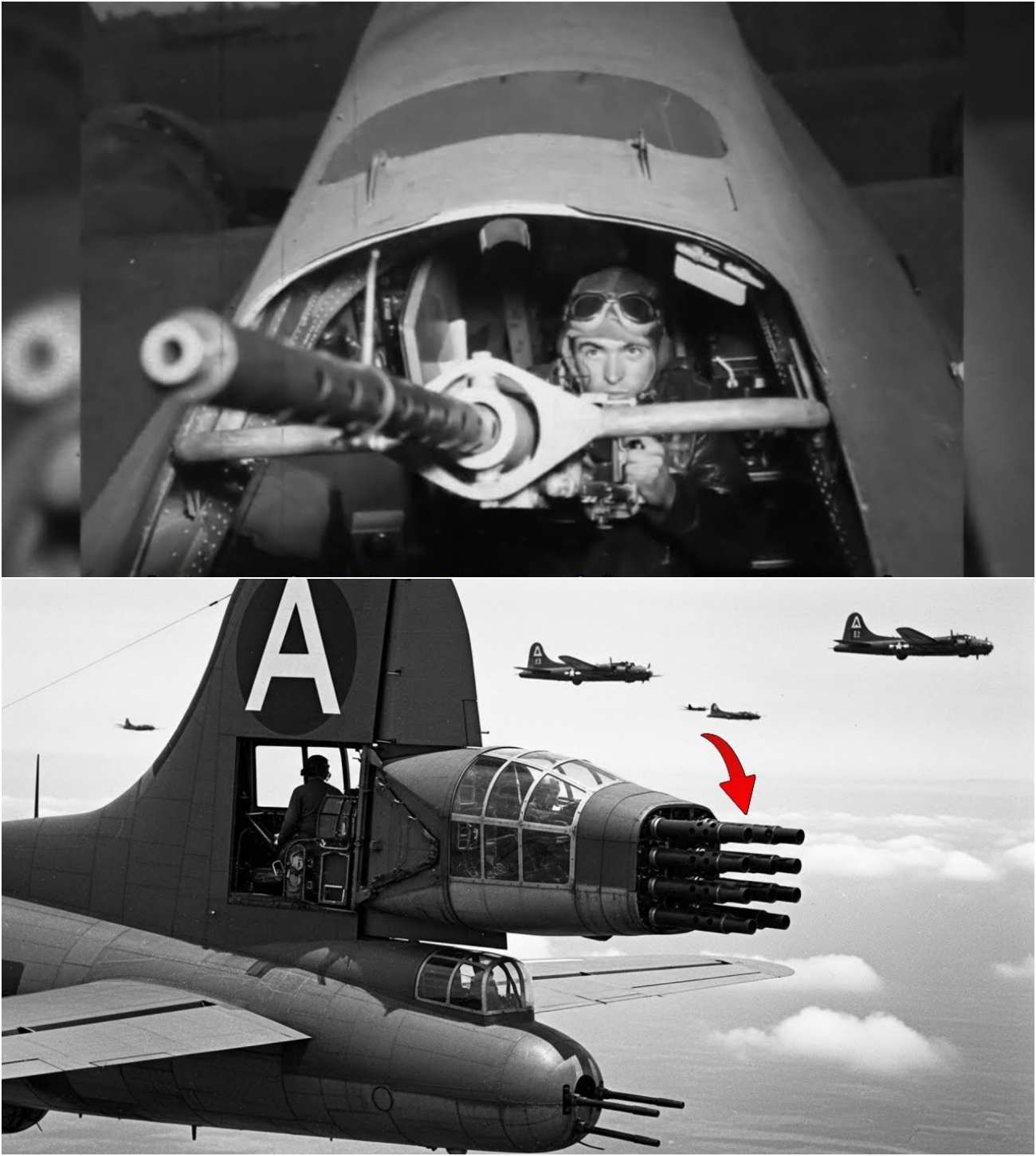

But today was different. Today, the Luftwaffe had positioned over 300 fighters along the route to Kassel, and the stakes were higher than ever. The tail gunner position, often referred to as the loneliest job in the war, measured a mere four feet wide and five feet long. It was cramped, with two Browning M2 .50 caliber machine guns pointing backward through a plexiglass window. At 25,000 feet, the temperature outside would plummet to -60°F, and his electrically heated suit was the only thing standing between him and death by hypothermia.

A Dangerous Duty

The statistics told a grim tale. In the summer of 1943, the average B-17 crew survived only 11 missions before being shot down, killed, or captured. Tail gunners suffered the highest casualty rates, targeted first by German fighter pilots who preferred attacking from the rear. The tail position absorbed the initial bullets, and many gunners never got the chance to fire back.

Aruth had witnessed the horrors firsthand. On his sixth mission, a B-17 flying off Tandleo’s right wing took a direct hit to the tail section. The gunner never fired a shot; the fighter came in fast, guns blazing, and the first rounds punched through the plexiglass before the American could react. The bomber fell out of formation, trailing smoke. Eight parachutes emerged, but the tail gunner was not among them.

The official doctrine demanded patience. Aruth questioned everything about it. The fighters attacked from maximum range because they knew American gunners would hold their fire. The Luftwaffe pilots exploited the training manual like a road map. “If you want to see how I challenged the doctrine that was getting tail gunners killed, please hit that like button,” he thought bitterly, knowing that the reality of war was far from the manuals.

A Mission Begins

On July 30, 1943, 186 B-17s lifted off from bases across eastern England. 123 P-47 Thunderbolts would escort them partway, but fuel limitations meant the fighters would turn back over Belgium. The bombers would fly the final 200 miles to Kassel alone. Aruth checked his ammunition belts—400 rounds per gun, 800 total. The manual said that was enough for a standard mission, but Aruth had already decided the manual was wrong about everything else.

The formation crossed the English Channel at 14,000 feet. Still climbing, Aruth watched the water recede through his plexiglass window, the white cliffs of Dover shrinking to a pale line on the horizon. Ahead lay occupied France, then Belgium, and finally the heart of Nazi Germany. The P-47 escorts held position around the bomber stream, offering a sense of security, but Aruth knew the arithmetic. The Thunderbolts carried enough fuel for roughly 90 minutes of combat flying. The mission to Kassel would take six hours. For most of the journey, the bombers would fly alone.

A Dangerous Encounter

At 11:42 AM, the first measures appeared, climbing from the southeast in groups of four. Aruth counted eight, then twelve, and then stopped counting. The sky behind Tandleo filled with black crosses on yellow noses. The lead fighter began its attack run from the 6:00 high position, diving toward the bomber formation at 400 mph.

Aruth tracked the aircraft through his gunsight, watching the wingspan grow larger with each passing second. At 800 yards, he squeezed both triggers. The twin Brownings roared to life, sending a stream of tracers across the sky. The first rounds fell short, disappearing into empty air below the diving fighter. Aruth adjusted, walking the fire upward. At 600 yards, the tracers began connecting, bright flashes sparking along the Messerschmitt’s engine cowling.

The German pilot broke hard right, smoke trailing from his aircraft. He never completed his firing pass. The fighter spiraled downward, disappearing into the cloud layer below. Aruth had no time to watch; the second attacker was already closing. This one came in lower, trying to slip beneath Aruth’s field of fire. The angle was difficult, requiring him to depress his guns nearly to their mechanical limit. He fired anyway, sending a long burst toward the approaching fighter.

The Focke-Wulf pilot flinched, pulling up early and releasing his cannon shells into empty sky above Tandleo. The attacks continued for 47 minutes. Wave after wave of German fighters slashed through the bomber formation, targeting stragglers and damaged aircraft. Aruth fired at everything that came within range, burning through ammunition at three times the recommended rate. His gun barrels glowed red from sustained fire.

A Fight for Survival

At 12:29 PM, a BF-109 approached from directly astern, flying straight and level. The pilot had either extraordinary courage or poor judgment. Aruth centered the fighter in his gunsight and held the triggers down. The Brownings hammered for six continuous seconds, pouring over 100 rounds into the approaching aircraft. The Messerschmitt disintegrated. The engines separated from the fuselage. The wings folded backward. What remained of the fighter tumbled past Tandleo, close enough for Aruth to see the empty cockpit. The pilot had either ejected or died at the controls.

Two confirmed kills. Ammunition down to 180 rounds. The formation reached Kassel at 12:51 PM and began its bombing run. For 11 minutes, the bombers flew straight and level, unable to maneuver while the bombers lined up their targets. The Luftwaffe knew this moment represented maximum vulnerability. The fighters pressed their attacks with renewed fury.

A Focke-Wulf 190 dove on Tandleo from the 5:00 position. Aruth swung his guns to meet it, firing a short burst. The rounds struck the fighter’s wing root. The pilot kept coming, cannon shells tearing through Tandleo’s tail section. Aruth felt the impacts before he felt the pain. 20 mm fragments ripped through the plexiglass, shredding his flight suit and burying themselves in his left arm and shoulder.

His left gun jammed. Hydraulic fluid sprayed across the compartment. He kept firing with the right gun. One-handed, bleeding, he tracked the wounded Focke-Wulf as it pulled away. A final burst caught the fighter’s tail assembly. The aircraft snap-rolled and dove toward the ground. His third kill of the mission.

A Hard Landing

The intercom crackled with voices from the crew. Someone was asking about damage. Someone else reported flak ahead. Aruth tried to respond, but his throat had gone dry. Blood pooled on the floor of his compartment, freezing almost instantly in the sub-zero air. 400 rounds expended. 63 remaining. Three German fighters destroyed. And the mission was only half over. Tandleo still had to fly 250 miles back to England through the same gauntlet of fighters that had nearly killed him on the way in.

Aruth wrapped a scarf around his wounded arm and waited for the next attack. The return flight began at 1:04 PM. Tandleo turned westward with 185 other bombers, leaving Kassel burning beneath a column of black smoke. Aruth remained at his position, scanning the sky through blood-smeared plexiglass. The Luftwaffe was not finished.

German fighters regrouped over Belgium, positioning themselves along the bomber stream’s route to the English Channel. Fresh aircraft replaced those lost or damaged in the morning attacks. The second gauntlet would be as dangerous as the first. Aruth’s left arm had gone numb from the cold and the wounds. His jammed gun remained inoperable. He had one functioning weapon and 63 rounds of ammunition to cover 250 miles of hostile airspace.

A Calculated Risk

At 1:31 PM, a pair of BF-109s closed from the 7:00 position. Aruth waited until 500 yards, then fired a precise 12-round burst at the lead fighter. The tracers struck the engine cowling. The Messerschmitt rolled inverted and dove away, trailing glycol coolant. The wingmen broke off without attacking. 51 rounds remaining.

Tandleo crossed into France at 2:15 PM. The fighter attacks diminished as the Luftwaffe reached the limit of their operational range. By 2:47 PM, the bomber formation had outrun the last German interceptors. The English Channel appeared on the horizon 20 minutes later. The landing at Kimbolton came at 3:52 PM.

Aruth could not climb out of his compartment without assistance. Ground crew pulled him through the narrow hatch and carried him to a waiting ambulance. The flight surgeon counted 11 separate fragment wounds in his arm, shoulder, and upper back. Word spread through the 379th Bombardment Group. Within hours, the tail gunner on Tandleo had scored three confirmed kills and two probables while wounded, operating a single gun with 63 rounds of ammunition.

The mission intelligence report noted his early engagement technique as a contributing factor to the bomber’s survival. Other tail gunners began asking questions. The standard doctrine said, “Wait until 300 yards.” Aruth had opened fire at 800. The doctrine said to conserve ammunition. Aruth had burned through 700 rounds before getting hit. The doctrine produced dead gunners. Aruth was still alive.

A Change in Doctrine

The 527th squadron’s gunnery officer reviewed the combat footage from Tandleo’s mission. The gun camera showed Aruth’s tracers reaching out far beyond normal engagement range, disrupting attack runs before the German pilots could establish firing solutions. The early fire forced the enemy to maneuver, degrading their accuracy and reducing hits on the bomber.

By mid-August, three other tail gunners in the squadron had adopted variations of Aruth’s technique. Their survival rates improved. The bombers they protected returned with less damage. The correlation was difficult to ignore. The 379th group commander received a preliminary report on September 1st. The data suggested that aggressive early fire reduced bomber casualties by disrupting coordinated fighter attacks.

The implications challenged two years of established gunnery doctrine. Meanwhile, Aruth recovered from his wounds at the station hospital. The fragment damage had missed major blood vessels and nerves. The flight surgeon cleared him for duty on August 19th, three weeks after the Kassel mission. Tandleo had a new aircraft waiting.

The old bomber had been written off after accumulating too much battle damage for economical repair. The replacement carried the same name and the same crew. Aruth climbed back into the tail position on August 26th. The Luftwaffe had noticed something changing in the American bomber formations. Their intelligence officers were studying the problem.

An Evolving Threat

Luftwaffe intelligence officers noticed the pattern in early September. American tail gunners were opening fire earlier, sometimes at ranges exceeding 600 yards. The change disrupted attack formations that had worked reliably for months. German fighter pilots reported the shift in debriefings across occupied Europe.

The approach from 6:00, once the safest angle against B-17 formations, was becoming increasingly dangerous. Tracers reached out before pilots could establish stable firing platforms. The psychological effect was significant. A pilot watching tracers stream toward his aircraft at long range instinctively maneuvered even when the rounds were falling short.

The Luftwaffe’s tactical response came in three phases. First, they increased approach speeds, diving on bomber formations at maximum velocity to reduce exposure time. Second, they shifted attack angles, approaching from the high 6:00 position where gravity would assist their pull-out. Third, they began targeting specific aircraft that appeared to have aggressive gunners, hoping to eliminate the threat before it could spread.

None of these adaptations solved the fundamental problem. Faster approaches meant less accurate shooting. Steeper angles increased the difficulty of tracking targets through the dive. Targeting aggressive gunners required identifying them in advance, which was nearly impossible in the chaos of a running air battle.

The 379th Bombardment Group flew 11 missions between August 26th and September 5th. Aruth participated in four of them, adding two more confirmed kills to his record. Other tail gunners in the group claimed an additional seven. The Luftwaffe’s loss ratio against the Triangle K bombers was climbing. German fighter commanders tried concentrating their attacks. Instead of spreading interceptors across the entire bomber stream, they masked against single groups, hoping to overwhelm defensive fire through sheer numbers.

The tactic produced results on September 3rd when concentrated attacks against the 100th Bombardment Group destroyed eight aircraft in 15 minutes. The 379th escaped that slaughter by flying in a different position within the combat box. But the lesson was clear: the Luftwaffe was adapting, searching for weaknesses in the new defensive approach.

The Stuttgart Mission

The air war over Europe had become a contest of tactical innovation, with each side studying the other’s methods and developing countermeasures. Aruth understood the stakes. His technique worked because it surprised the enemy. Once the Germans developed effective responses, the advantage would disappear. Every mission was a test, every engagement a data point that both sides would analyze.

The mission scheduled for September 6th would target Stuttgart deep in southern Germany. The route would carry the bombers over 500 miles of enemy territory—the longest penetration the Eighth Air Force had attempted that month. Intelligence predicted heavy fighter opposition from bases in France, Belgium, and Germany itself. Stuttgart manufactured ball bearings, components essential to every vehicle, aircraft, and weapon in the German arsenal. The strategic importance made it one of the most heavily defended targets in Europe.

The briefing on September 5th laid out the challenge. The 379th would fly in the lead position of the combat wing, responsible for navigation and bomb aiming for the formations following behind. Lead position meant absorbing the first fighter attacks. It meant flying straight and level while other groups maneuvered. It meant maximum exposure to everything the Luftwaffe could throw at them.

Aruth checked his guns that evening. Both Brownings were freshly serviced, the feed mechanism smooth, the barrels replaced after accumulating too many rounds. He loaded 1,200 rounds instead of the standard 800. The extra ammunition added weight, but weight seemed less important than firepower. Tomorrow would test everything he had learned. Tomorrow would determine whether his methods could survive the most dangerous mission of his career.

The Mission Launches

The Stuttgart mission launched at 0540 on September 6th. 187 bombers climbed into an overcast English sky, forming up over the North Sea before turning southeast toward occupied Europe. Tandleo flew in the lead element of the 379th formation, positioned where Aruth would face the first attacks from any direction.

The fighters found them over France at 0915. Messerschmitts and Focke-Wulfs rose from airfields across the region, climbing to intercept the bomber stream before it reached German airspace. The initial attacks came from the 11:00 position, head-on passes that tested the nose gunners rather than the tail. Aruth waited, watching contrails multiply behind the formation.

The Luftwaffe was building strength, assembling fighters from multiple units into a concentrated force. By 0940, intelligence estimates counted over 100 interceptors tracking the bombers. The rear attacks began at 10:08. A staffel of 12 BF-109s positioned themselves 2,000 feet below the formation, then pulled up in a climbing attack from the 6:00 low.

Aruth opened fire at 700 yards, sending tracers into the lead element. Two fighters broke off immediately. A third absorbed multiple hits and fell away smoking. The remaining nine pressed their attack. Cannon shells ripped through the formation, striking bombers throughout the 379th combat box.

The B-17 flying off Tandleo’s left wing took hits to its number three engine. Another bomber in the low squadron began trailing fuel from ruptured tanks. Aruth kept firing, shifting from target to target as fighters flashed through his field of view. His ammunition counter dropped steadily—600 rounds, 500, 400. The attacks showed no sign of diminishing.

A Critical Moment

At 10:31, a Focke-Wulf 190 dove on Tandleo from directly above and behind, using the sun to mask its approach. Aruth spotted the fighter too late. The 20 mm shells punched through the tail section before he could bring his guns to bear. The impacts threw him against the plexiglass. His left gun was destroyed, the receiver shattered by a direct hit. Fragments tore through his flight suit, opening wounds across his arms and scalp. Blood poured down his face, partially blinding him.

He kept firing with the right gun. One-handed, bleeding, he tracked the wounded Focke-Wulf as it pulled away. A final burst caught the fighter’s tail assembly. The aircraft snap-rolled and dove toward the ground. His third kill of the mission. The intercom crackled with voices from the crew. Someone was asking about damage. Someone else reported flak ahead.

Aruth tried to respond, but his throat had gone dry. Blood pooled on the floor of his compartment, freezing almost instantly in the sub-zero air. 400 rounds expended. 63 remaining. Three German fighters destroyed. And the mission was only half over. Tandleo still had to fly 250 miles back to England through the same gauntlet of fighters that had nearly killed him on the way in.

Aruth wrapped a scarf around his wounded arm and waited for the next attack. The return flight began at 1:04 PM. Tandleo turned westward with 185 other bombers, leaving Stuttgart burning beneath a column of black smoke. Aruth remained at his position, scanning the sky through blood-smeared plexiglass. The Luftwaffe was not finished.

German fighters regrouped over Belgium, positioning themselves along the bomber stream’s route to the English Channel. Fresh aircraft replaced those lost or damaged in the morning attacks. The second gauntlet would be as dangerous as the first. Aruth’s left arm had gone numb from the cold and the wounds. His jammed gun remained inoperable. He had one functioning weapon and 63 rounds of ammunition to cover 250 miles of hostile airspace.

A Calculated Risk

At 1:31 PM, a pair of BF-109s closed from the 7:00 position. Aruth waited until 500 yards, then fired a precise 12-round burst at the lead fighter. The tracers struck the engine cowling. The Messerschmitt rolled inverted and dove away, trailing glycol coolant. The wingmen broke off without attacking. 51 rounds remaining.

Tandleo crossed into France at 2:15 PM. The fighter attacks diminished as the Luftwaffe reached the limit of their operational range. By 2:47 PM, the bomber formation had outrun the last German interceptors. The English Channel appeared on the horizon 20 minutes later. The landing at Kimbolton came at 3:52 PM.

Aruth could not climb out of his compartment without assistance. Ground crew pulled him through the narrow hatch and carried him to a waiting ambulance. The flight surgeon counted 11 separate fragment wounds in his arm, shoulder, and upper back. Word spread through the 379th Bombardment Group. Within hours, the tail gunner on Tandleo had scored three confirmed kills and two probables while wounded, operating a single gun with 63 rounds of ammunition.

The mission intelligence report noted his early engagement technique as a contributing factor to the bomber’s survival. Other tail gunners began asking questions. The standard doctrine said, “Wait until 300 yards.” Aruth had opened fire at 800. The doctrine said to conserve ammunition. Aruth had burned through 700 rounds before getting hit. The doctrine produced dead gunners. Aruth was still alive.

A Change in Doctrine

The 527th squadron’s gunnery officer reviewed the combat footage from Tandleo’s mission. The gun camera showed Aruth’s tracers reaching out far beyond normal engagement range, disrupting attack runs before the German pilots could establish firing solutions. The early fire forced the enemy to maneuver, degrading their accuracy and reducing hits on the bomber.

By mid-August, three other tail gunners in the squadron had adopted variations of Aruth’s technique. Their survival rates improved. The bombers they protected returned with less damage. The correlation was difficult to ignore. The 379th group commander received a preliminary report on September 1st. The data suggested that aggressive early fire reduced bomber casualties by disrupting coordinated fighter attacks.

The implications challenged two years of established gunnery doctrine. Meanwhile, Aruth recovered from his wounds at the station hospital. The fragment damage had missed major blood vessels and nerves. The flight surgeon cleared him for duty on August 19th, three weeks after the Stuttgart mission. Tandleo had a new aircraft waiting.

The old bomber had been written off after accumulating too much battle damage for economical repair. The replacement carried the same name and the same crew. Aruth climbed back into the tail position on August 26th. The Luftwaffe had noticed something changing in the American bomber formations. Their intelligence officers were studying the problem.

An Evolving Threat

Luftwaffe intelligence officers noticed the pattern in early September. American tail gunners were opening fire earlier, sometimes at ranges exceeding 600 yards. The change disrupted attack formations that had worked reliably for months. German fighter pilots reported the shift in debriefings across occupied Europe.

The approach from 6:00, once the safest angle against B-17 formations, was becoming increasingly dangerous. Tracers reached out before pilots could establish stable firing platforms. The psychological effect was significant. A pilot watching tracers stream toward his aircraft at long range instinctively maneuvered even when the rounds were falling short.

The Luftwaffe’s tactical response came in three phases. First, they increased approach speeds, diving on bomber formations at maximum velocity to reduce exposure time. Second, they shifted attack angles, approaching from the high 6:00 position where gravity would assist their pull-out. Third, they began targeting specific aircraft that appeared to have aggressive gunners, hoping to eliminate the threat before it could spread.

None of these adaptations solved the fundamental problem. Faster approaches meant less accurate shooting. Steeper angles increased the difficulty of tracking targets through the dive. Targeting aggressive gunners required identifying them in advance, which was nearly impossible in the chaos of a running air battle.

The 379th Bombardment Group flew 11 missions between August 26th and September 5th. Aruth participated in four of them, adding two more confirmed kills to his record. Other tail gunners in the group claimed an additional seven. The Luftwaffe’s loss ratio against the Triangle K bombers was climbing. German fighter commanders tried concentrating their attacks. Instead of spreading interceptors across the entire bomber stream, they masked against single groups, hoping to overwhelm defensive fire through sheer numbers.

The Stuttgart Mission

The air war over Europe had become a contest of tactical innovation, with each side studying the other’s methods and developing countermeasures. Aruth understood the stakes. His technique worked because it surprised the enemy. Once the Germans developed effective responses, the advantage would disappear. Every mission was a test, every engagement a data point that both sides would analyze.

The mission scheduled for September 6th would target Stuttgart deep in southern Germany. The route would carry the bombers over 500 miles of enemy territory—the longest penetration the Eighth Air Force had attempted that month. Intelligence predicted heavy fighter opposition from bases in France, Belgium, and Germany itself. Stuttgart manufactured ball bearings, components essential to every vehicle, aircraft, and weapon in the German arsenal. The strategic importance made it one of the most heavily defended targets in Europe.

The briefing on September 5th laid out the challenge. The 379th would fly in the lead position of the combat wing, responsible for navigation and bomb aiming for the formations following behind. Lead position meant absorbing the first fighter attacks. It meant flying straight and level while other groups maneuvered. It meant maximum exposure to everything the Luftwaffe could throw at them.

Aruth checked his guns that evening. Both Brownings were freshly serviced, the feed mechanism smooth, the barrels replaced after accumulating too many rounds. He loaded 1,200 rounds instead of the standard 800. The extra ammunition added weight, but weight seemed less important than firepower. Tomorrow would test everything he had learned. Tomorrow would determine whether his methods could survive the most dangerous mission of his career.

The Mission Launches

The Stuttgart mission launched at 0540 on September 6th. 187 bombers climbed into an overcast English sky, forming up over the North Sea before turning southeast toward occupied Europe. Tandleo flew in the lead element of the 379th formation, positioned where Aruth would face the first attacks from any direction.

The fighters found them over France at 0915. Messerschmitts and Focke-Wulfs rose from airfields across the region, climbing to intercept the bomber stream before it reached German airspace. The initial attacks came from the 11:00 position, head-on passes that tested the nose gunners rather than the tail. Aruth waited, watching contrails multiply behind the formation.

The Luftwaffe was building strength, assembling fighters from multiple units into a concentrated force. By 0940, intelligence estimates counted over 100 interceptors tracking the bombers. The rear attacks began at 10:08. A staffel of 12 BF-109s positioned themselves 2,000 feet below the formation, then pulled up in a climbing attack from the 6:00 low.

Aruth opened fire at 700 yards, sending tracers into the lead element. Two fighters broke off immediately. A third absorbed multiple hits and fell away smoking. The remaining nine pressed their attack. Cannon shells ripped through the formation, striking bombers throughout the 379th combat box.

The B-17 flying off Tandleo’s left wing took hits to its number three engine. Another bomber in the low squadron began trailing fuel from ruptured tanks. Aruth kept firing, shifting from target to target as fighters flashed through his field of view. His ammunition counter dropped steadily—600 rounds, 500, 400. The attacks showed no sign of diminishing.

A Critical Moment

At 10:31, a Focke-Wulf 190 dove on Tandleo from directly above and behind, using the sun to mask its approach. Aruth spotted the fighter too late. The 20 mm shells punched through the tail section before he could bring his guns to bear. The impacts threw him against the plexiglass. His left gun was destroyed, the receiver shattered by a direct hit. Fragments tore through his flight suit, opening wounds across his arms and scalp. Blood poured down his face, partially blinding him.

He kept firing with the right gun. One-handed, bleeding, he tracked the wounded Focke-Wulf as it pulled away. A final burst caught the fighter’s tail assembly. The aircraft snap-rolled and dove toward the ground. His third kill of the mission. The intercom crackled with voices from the crew. Someone was asking about damage. Someone else reported flak ahead.

Aruth tried to respond, but his throat had gone dry. Blood pooled on the floor of his compartment, freezing almost instantly in the sub-zero air. 400 rounds expended. 63 remaining. Three German fighters destroyed. And the mission was only half over. Tandleo still had to fly 250 miles back to England through the same gauntlet of fighters that had nearly killed him on the way in.

Aruth wrapped a scarf around his wounded arm and waited for the next attack. The return flight began at 1:04 PM. Tandleo turned westward with 185 other bombers, leaving Stuttgart burning beneath a column of black smoke. Aruth remained at his position, scanning the sky through blood-smeared plexiglass. The Luftwaffe was not finished.

German fighters regrouped over Belgium, positioning themselves along the bomber stream’s route to the English Channel. Fresh aircraft replaced those lost or damaged in the morning attacks. The second gauntlet would be as dangerous as the first. Aruth’s left arm had gone numb from the cold and the wounds. His jammed gun remained inoperable. He had one functioning weapon and 63 rounds of ammunition to cover 250 miles of hostile airspace.

A Calculated Risk

At 1:31 PM, a pair of BF-109s closed from the 7:00 position. Aruth waited until 500 yards, then fired a precise 12-round burst at the lead fighter. The tracers struck the engine cowling. The Messerschmitt rolled inverted and dove away, trailing glycol coolant. The wingmen broke off without attacking. 51 rounds remaining.

Tandleo crossed into France at 2:15 PM. The fighter attacks diminished as the Luftwaffe reached the limit of their operational range. By 2:47 PM, the bomber formation had outrun the last German interceptors. The English Channel appeared on the horizon 20 minutes later. The landing at Kimbolton came at 3:52 PM.

Aruth could not climb out of his compartment without assistance. Ground crew pulled him through the narrow hatch and carried him to a waiting ambulance. The flight surgeon counted 11 separate fragment wounds in his arm, shoulder, and upper back. Word spread through the 379th Bombardment Group. Within hours, the tail gunner on Tandleo had scored three confirmed kills and two probables while wounded, operating a single gun with 63 rounds of ammunition.

The mission intelligence report noted his early engagement technique as a contributing factor to the bomber’s survival. Other tail gunners began asking questions. The standard doctrine said, “Wait until 300 yards.” Aruth had opened fire at 800. The doctrine said to conserve ammunition. Aruth had burned through 700 rounds before getting hit. The doctrine produced dead gunners. Aruth was still alive.

A Change in Doctrine

The 527th squadron’s gunnery officer reviewed the combat footage from Tandleo’s mission. The gun camera showed Aruth’s tracers reaching out far beyond normal engagement range, disrupting attack runs before the German pilots could establish firing solutions. The early fire forced the enemy to maneuver, degrading their accuracy and reducing hits on the bomber.

By mid-August, three other tail gunners in the squadron had adopted variations of Aruth’s technique. Their survival rates improved. The bombers they protected returned with less damage. The correlation was difficult to ignore. The 379th group commander received a preliminary report on September 1st. The data suggested that aggressive early fire reduced bomber casualties by disrupting coordinated fighter attacks.

The implications challenged two years of established gunnery doctrine. Meanwhile, Aruth recovered from his wounds at the station hospital. The fragment damage had missed major blood vessels and nerves. The flight surgeon cleared him for duty on August 19th, three weeks after the Stuttgart mission. Tandleo had a new aircraft waiting.

The old bomber had been written off after accumulating too much battle damage for economical repair. The replacement carried the same name and the same crew. Aruth climbed back into the tail position on August 26th. The Luftwaffe had noticed something changing in the American bomber formations. Their intelligence officers were studying the problem.

An Evolving Threat

Luftwaffe intelligence officers noticed the pattern in early September. American tail gunners were opening fire earlier, sometimes at ranges exceeding 600 yards. The change disrupted attack formations that had worked reliably for months. German fighter pilots reported the shift in debriefings across occupied Europe.

The approach from 6:00, once the safest angle against B-17 formations, was becoming increasingly dangerous. Tracers reached out before pilots could establish stable firing platforms. The psychological effect was significant. A pilot watching tracers stream toward his aircraft at long range instinctively maneuvered even when the rounds were falling short.

The Luftwaffe’s tactical response came in three phases. First, they increased approach speeds, diving on bomber formations at maximum velocity to reduce exposure time. Second, they shifted attack angles, approaching from the high 6:00 position where gravity would assist their pull-out. Third, they began targeting specific aircraft that appeared to have aggressive gunners, hoping to eliminate the threat before it could spread.

None of these adaptations solved the fundamental problem. Faster approaches meant less accurate shooting. Steeper angles increased the difficulty of tracking targets through the dive. Targeting aggressive gunners required identifying them in advance, which was nearly impossible in the chaos of a running air battle.

The 379th Bombardment Group flew 11 missions between August 26th and September 5th. Aruth participated in four of them, adding two more confirmed kills to his record. Other tail gunners in the group claimed an additional seven. The Luftwaffe’s loss ratio against the Triangle K bombers was climbing. German fighter commanders tried concentrating their attacks. Instead of spreading interceptors across the entire bomber stream, they masked against single groups, hoping to overwhelm defensive fire through sheer numbers.

The Stuttgart Mission

The air war over Europe had become a contest of tactical innovation, with each side studying the other’s methods and developing countermeasures. Aruth understood the stakes. His technique worked because it surprised the enemy. Once the Germans developed effective responses, the advantage would disappear. Every mission was a test, every engagement a data point that both sides would analyze.

The mission scheduled for September 6th would target Stuttgart deep in southern Germany. The route would carry the bombers over 500 miles of enemy territory—the longest penetration the Eighth Air Force had attempted that month. Intelligence predicted heavy fighter opposition from bases in France, Belgium, and Germany itself. Stuttgart manufactured ball bearings, components essential to every vehicle, aircraft, and weapon in the German arsenal. The strategic importance made it one of the most heavily defended targets in Europe.

The briefing on September 5th laid out the challenge. The 379th would fly in the lead position of the combat wing, responsible for navigation and bomb aiming for the formations following behind. Lead position meant absorbing the first fighter attacks. It meant flying straight and level while other groups maneuvered. It meant maximum exposure to everything the Luftwaffe could throw at them.

Aruth checked his guns that evening. Both Brownings were freshly serviced, the feed mechanism smooth, the barrels replaced after accumulating too many rounds. He loaded 1,200 rounds instead of the standard 800. The extra ammunition added weight, but weight seemed less important than firepower. Tomorrow would test everything he had learned. Tomorrow would determine whether his methods could survive the most dangerous mission of his career.

The Mission Launches

The Stuttgart mission launched at 0540 on September 6th. 187 bombers climbed into an overcast English sky, forming up over the North Sea before turning southeast toward occupied Europe. Tandleo flew in the lead element of the 379th formation, positioned where Aruth would face the first attacks from any direction.

The fighters found them over France at 0915. Messerschmitts and Focke-Wulfs rose from airfields across the region, climbing to intercept the bomber stream before it reached German airspace. The initial attacks came from the 11:00 position, head-on passes that tested the nose gunners rather than the tail. Aruth waited, watching contrails multiply behind the formation.

The Luftwaffe was building strength, assembling fighters from multiple units into a concentrated force. By 0940, intelligence estimates counted over 100 interceptors tracking the bombers. The rear attacks began at 10:08. A staffel of 12 BF-109s positioned themselves 2,000 feet below the formation, then pulled up in a climbing attack from the 6:00 low.

Aruth opened fire at 700 yards, sending tracers into the lead element. Two fighters broke off immediately. A third absorbed multiple hits and fell away smoking. The remaining nine pressed their attack. Cannon shells ripped through the formation, striking bombers throughout the 379th combat box.

The B-17 flying off Tandleo’s left wing took hits to its number three engine. Another bomber in the low squadron began trailing fuel from ruptured tanks. Aruth kept firing, shifting from target to target as fighters flashed through his field of view. His ammunition counter dropped steadily—600 rounds, 500, 400. The attacks showed no sign of diminishing.