How America Built 1,000 Miles of Railroad Through Mountains Before Bulldozers

On January 8th, 1863, in a muddy ceremony in Sacramento, California, a crowd gathered to witness history. Governor Leland Stanford drove a ceremonial silver spike into a railroad tie, marking the official beginning of construction for the Central Pacific Railroad. The goal was audacious—to build a railroad east from Sacramento, across the Flat Valley, up and over the Sierra Nevada mountains, through Nevada, and across the desert to meet the Union Pacific Railroad, which was building west from Omaha. This monumental project aimed to create the first transcontinental railroad, a continuous line of iron spanning the entire width of the United States.

The Union Pacific had the easier route—flat prairie and wide-open terrain, with only minor hills to navigate. The Central Pacific, however, faced the daunting Sierra Nevada, a wall of granite rising 7,000 feet high, covered in snow for eight months of the year. The slopes were so steep that a man standing upright had to lean forward to avoid falling backward. There were no natural passes at the right elevation, and the railroad would have to be carved into the mountains using hand tools, black powder, and sheer human labor.

The men who undertook this monumental task were primarily Chinese immigrants, Irish laborers, and a scattering of Civil War veterans who had survived one kind of hell and were about to enter another. Between 1863 and 1869, these men would move more rock and dirt than had ever been moved in any construction project in American history up to that point. They built over 1,000 miles of railroad through terrain that engineers deemed impossible, and they did it without engines, machinery, bulldozers, or excavators—only shovels, pickaxes, wheelbarrows, black powder, and hands that bled until they calloused into leather.

#### The Harsh Reality of Construction

The Sierra Nevada is a granite batholith, a massive intrusion of igneous rock that cooled and solidified millions of years ago. It is not sedimentary stone that can be chipped away with a pickaxe; it is dense, crystalline granite, harder than most steel. A man swinging a sledgehammer against Sierra granite could work all day and make a dent measured in inches. But the Central Pacific didn’t need inches—they needed tunnels.

Fifteen tunnels, some over 1,600 feet long, had to be bored through solid rock at elevations above 7,000 feet. The longest, the Summit Tunnel, would require boring through 1,659 feet of granite at an elevation where snow fell from October through May, and temperatures dropped to 20 degrees below zero. Engineers knew it was theoretically possible; tunnels had been built through mountains before in Europe using similar methods, but those projects had taken decades. The Central Pacific didn’t have decades. They had investors demanding returns, competition from the Union Pacific, and a federal charter that paid them per mile of completed track.

To expedite the construction, engineers led by Theodore Judah and later by chief engineer Samuel Montague devised a plan: hire as many men as possible, work around the clock, and accept that some of them would die. The workforce began as a mix of Irish immigrants fleeing famine, Civil War veterans, drifters, and miners who had gone bust in the gold fields. However, the work was brutal, and the pay, while decent, wasn’t enough to keep men on the job for long. Workers would sign on, last a few weeks, and quit.

By 1864, the Central Pacific was desperate for labor. Charles Crocker, one of the “Big Four” investors and the man in charge of construction, made a decision that would define the project: he started hiring Chinese workers. Thousands of Chinese immigrants had come to California, most veterans of the Gold Rush who had been pushed out of mining camps by racial violence and restrictive laws. They worked in restaurants and agriculture, often paid less than white workers and lacking legal protections. Crocker saw them as a valuable resource—available, cheap, and, contrary to popular racist assumptions, incredibly hardworking.

Within a year, the Central Pacific workforce was over 90% Chinese. At the peak of construction, more than 12,000 Chinese laborers were working on the railroad, doing the hardest and most dangerous work. They blasted tunnels, built retaining walls, and graded roads on slopes so steep that men worked roped together to prevent falls. They did it for less money and in worse conditions than any white worker would accept.

#### The Nightmare of Tunnel Work

The tunnel work was where the real nightmare lay. Boring a tunnel through granite with 1860s technology was a process of unimaginable tedium and danger. There were no tunnel boring machines or pneumatic drills. The method was simple and brutal: drill holes in the rock face using hand drills, pack the holes with black powder, light the fuse, and run. Then, they would wait for the explosion, clear the rubble, and repeat.

A single round of drilling, blasting, and clearing might advance the tunnel face by 18 inches—maybe 2 feet if the rock cooperated. The Summit Tunnel was being attacked from both ends and from a central shaft sunk from above. Even working from four faces simultaneously, the progress was measured in feet per week. Drilling crews worked in teams of three: one man held the steel drill, while the other two swung sledgehammers in alternating rhythm. The noise in the confined space of the tunnel was deafening, with the ringing of steel on steel echoing off the granite walls.

The air was thick with rock dust that coated their lungs and left them coughing blood by the end of a shift. They worked by candlelight or oil lamps, and ventilation was poor. The smoke from the lamps mixed with the dust, making it hard to breathe. And this was before the blasting.

Once a series of holes had been drilled—usually six to ten holes per round—the blasting crew would take over. Black powder was packed into the holes using wooden tamping rods, and a fuse was inserted. The fuses were cut to length based on how much time was needed to get clear, usually 60 to 90 seconds. But fuses were unpredictable; they could burn fast or slow, sputter out, or ignite faster than expected.

When the blasting crew lit the fuses, they started with the ones farthest from the tunnel entrance, then worked their way back, lighting each one in sequence before running out of the tunnel into the open air. They would wait for the explosions, which were violent. The confined space of the tunnel amplified the shock wave. Even outside, one could feel the concussion in their chest. Inside, if caught, the blast could rupture lungs, shatter eardrums, or bury men under tons of rock.

Premature explosions killed men—either from a fuse burning faster than expected or a spark from a hammer strike igniting loose powder. In September 1866, a premature blast in the Summit Tunnel killed four Chinese workers instantly. Their bodies were buried under rubble, and it took two days to dig them out. Company records listed them simply as “Chinese laborers,” with names unknown. They were buried in a mass grave near the tunnel entrance, and work resumed the next day.

After each blast, the clearing crews moved in. The rubble—broken rock and granite fragments—had to be removed before the next round of drilling could begin. This was done by hand, with men using shovels and wheelbarrows. A single blast might produce 20 to 30 tons of rubble, all of which had to be cleared before progress could continue. The work was exhausting: shovel, load, push, dump, repeat. Shift after shift.

The Summit Tunnel took over two years to complete—two years of round-the-clock work, two years of drilling, blasting, and clearing. And that was just one tunnel. There were 14 others, some shorter, some nearly as long, each requiring the same brutal process, the same labor, and the same risk. The men doing this work were being paid $30 a month—about a dollar a day. White workers were paid $35 a month plus room and board. Chinese workers had to buy their own food and lived in crude shelters built from scrap lumber and canvas.

#### The Harsh Winter

In the winter, when the snow reached 20 feet deep, the camps were buried. The workers lived and worked in tunnels dug through the snow, and some of these snow tunnels collapsed, burying men alive. The winter of 1866 to 1867 was one of the worst on record, with snow falling continuously from November through March. At the summit, the snowpack reached 40 feet in places, and avalanches were constant.

An avalanche didn’t give warnings. One moment, the snow was stable; the next, the entire slope was sliding, carrying men, equipment, and camps with it. In February 1867, an avalanche swept through a Chinese labor camp near Donner Pass. The camp was gone in seconds, buried under 30 feet of compacted snow. Estimates suggest that between 20 and 40 men were in the camp at the time, and their bodies were never recovered. When the snow melted in June, their remains were found scattered across the slope, buried where they fell.

But the work didn’t stop. The Central Pacific kept pushing forward, bringing in more workers, rebuilding camps, and advancing the tunnels foot by foot. Slowly, impossibly, the railroad took shape. East of the summit, the terrain opened up, shifting the work from tunneling to grading. Grading meant creating a level roadbed for the tracks.

In flat terrain, this was relatively simple—clear the brush and lay the ties. But in the mountains and across Nevada, the challenges were immense. The roadbed had to be cut into hillsides, built up across gullies, and bridged over canyons. Cutting a roadbed into a hillside was done with picks and shovels. A crew would mark the line of the grade, then start digging.

On the uphill side, they cut into the slope, removing dirt and rock to create a level shelf. On the downhill side, they built up a retaining wall using the excavated material. If the slope was steep, the retaining wall had to be reinforced with timber or stone to prevent collapse. The work was slow; a crew of 50 men might advance the grade by a few hundred feet in a day.

The Chinese workers excelled at this kind of detailed, precise work. They built retaining walls that are still standing today, 150 years later—dry stone walls fitted together without mortar, designed to flex and settle without collapsing. They graded roads on slopes where a misstep could lead to a fall of hundreds of feet, working roped together, chipping footholds into the rock, and hauling materials using pulleys and woven baskets.

#### The Harsh Realities of the Desert

On the flat lands of Nevada, the challenge was different. The terrain was desert—alkaline soil, no water, and summer temperatures exceeding 110 degrees Fahrenheit. The workers, still predominantly Chinese, graded hundreds of miles of roadbed across this wasteland. They lived in temporary camps that moved with the work. Water had to be hauled in by wagon from distant wells, and food supplies came by wagon train from Sacramento, a journey that took weeks.

The camps were brutal—dust storms, scorpions, rattlesnakes, and the heat. Men died from heat stroke, dehydration, and accidents. The company didn’t keep detailed records of the deaths, and the number remains unknown. Estimates suggest that over 1,000 Chinese workers died during the construction of the Central Pacific line, some from accidents, some from disease, and some from exposure. Their graves, if they were buried, are lost.

While the Central Pacific clawed its way east through the mountains, the Union Pacific was racing west across the plains. The Union Pacific had its own labor force, predominantly Irish immigrants, Civil War veterans, and freed slaves. Their challenges were different but no less brutal. The plains were flat, but they were also empty. No trees for timber, no stone for ballast—everything had to be hauled in.

The Native American tribes—the Lakota, the Cheyenne, the Pawnee—saw the railroad as an invasion. They were right. The railroad brought settlers, soldiers, and buffalo hunters who would destroy the herds the tribes depended on. The tribes fought back, raiding work camps, tearing up rails, and attacking supply trains. The Union Pacific hired guards—former soldiers—to protect the workers. The construction became a slow-moving war.

The grading crews on the Union Pacific faced their own dangers: accidents with black powder, floods that washed out miles of roadbed, harsh winters on the high plains where temperatures dropped below zero, and winds that cut through clothing like a blade. Men froze to death in their tents, and others died from disease. Cholera and dysentery spread through the camps, killing dozens. The company pushed forward, fueled by fierce competition with the Central Pacific.

By 1868, both railroads were making rapid progress. The Central Pacific had cleared the Sierra Nevada and was laying track across Nevada at a rate of over a mile per day. The Union Pacific was pushing through Wyoming, heading toward Utah. The two lines were converging, and the race to finish became a national spectacle, covered by newspapers and followed by eager spectators.

#### The Historic Meeting

On April 28th, 1869, the Central Pacific set a record by laying 10 miles of track in a single day. Ten miles—that’s over 3,000 ties placed, over 25,000 spikes driven, and 50,000 pounds of rail lifted, positioned, and spiked down. The feat required coordination, speed, and endurance that seems impossible, but it happened. The two railroads met at Promontory Summit, Utah, on May 10th, 1869.

A crowd gathered, dignitaries from both companies, photographers, and reporters. The ceremony featured speeches, handshakes, and the driving of a golden spike to symbolize the completion of the transcontinental railroad. The photographs from that day show well-dressed men in suits posing in front of the locomotives, but what those photographs don’t show are the Chinese workers. They were not invited to the ceremony.

Despite having built more than half the Central Pacific line and having done the hardest and most dangerous work, they were excluded from the celebration. The official narrative erased them, and the celebration belonged to the investors, the engineers, and the white workers. The Chinese went back to their camps, packed their tools, and dispersed. Most returned to California, while some stayed and found work maintaining the line. Others moved on to new construction projects.

Their contributions were forgotten for decades. Yung Wing, Hungwa, Chin, and Linso are three of the very few names recorded of the thousands of Chinese workers who built the railroad. Most were listed only as “Chinese laborers” in company records—no first names, no ages, no hometowns. When they died, they were buried in mass graves or their bodies were shipped back to China if families could afford it.

The Central Pacific kept minimal records of these deaths. There was no legal requirement to report them, no oversight, and no accountability. The men were expendable, and they knew it. If you believe that the memory of those men—the ones who blasted tunnels through granite and laid track across deserts, whose names were never recorded but whose work is still carrying freight today—matters, you should reflect on their legacy.

#### The Human Cost of Progress

The construction of the transcontinental railroad killed an estimated 1,500 to 2,000 workers. The exact number will never be known, as the companies didn’t keep comprehensive records, and the graves are scattered across a thousand miles of mountains, plains, and desert. Some are marked, but most are not. The railroad they built changed the United States; it connected the coasts, made travel that had taken six months by wagon possible in six days by train, and enabled the settlement of the West.

But it was also built on exploitation, on the labor of men who were treated as disposable, and on the destruction of Native American lands and ways of life. The railroad brought settlers who displaced the tribes and buffalo hunters who slaughtered the herds to near extinction. The tribes knew what the railroad meant, and they fought it. They lost.

The physical remnants of the construction are still visible today. In the Sierra Nevada, you can hike to the sites of the old tunnels—some still in use, widened and reinforced, carrying modern freight. Others are abandoned, sealed off, slowly being reclaimed by the mountains. The roadbed, the graded shelf cut into the hillsides, is still there, overgrown with trees and brush but recognizable to anyone who knows what to look for.

The retaining walls built by Chinese workers 150 years ago still stand, stones fitted so precisely that they haven’t shifted. In Nevada and Utah, the old grade is visible from the air—a scar running across the desert, parallel to the modern tracks. The wooden ties have long since rotted, and the rails were salvaged and reused, but the shape of the roadbed remains.

Scattered along the line are the graves—small markers and forgotten cemeteries, piles of stones in the desert, places where workers were buried where they fell and never moved. Some of these graves have been located and documented by historians and archaeologists, but many remain lost.

#### Honoring the Legacy

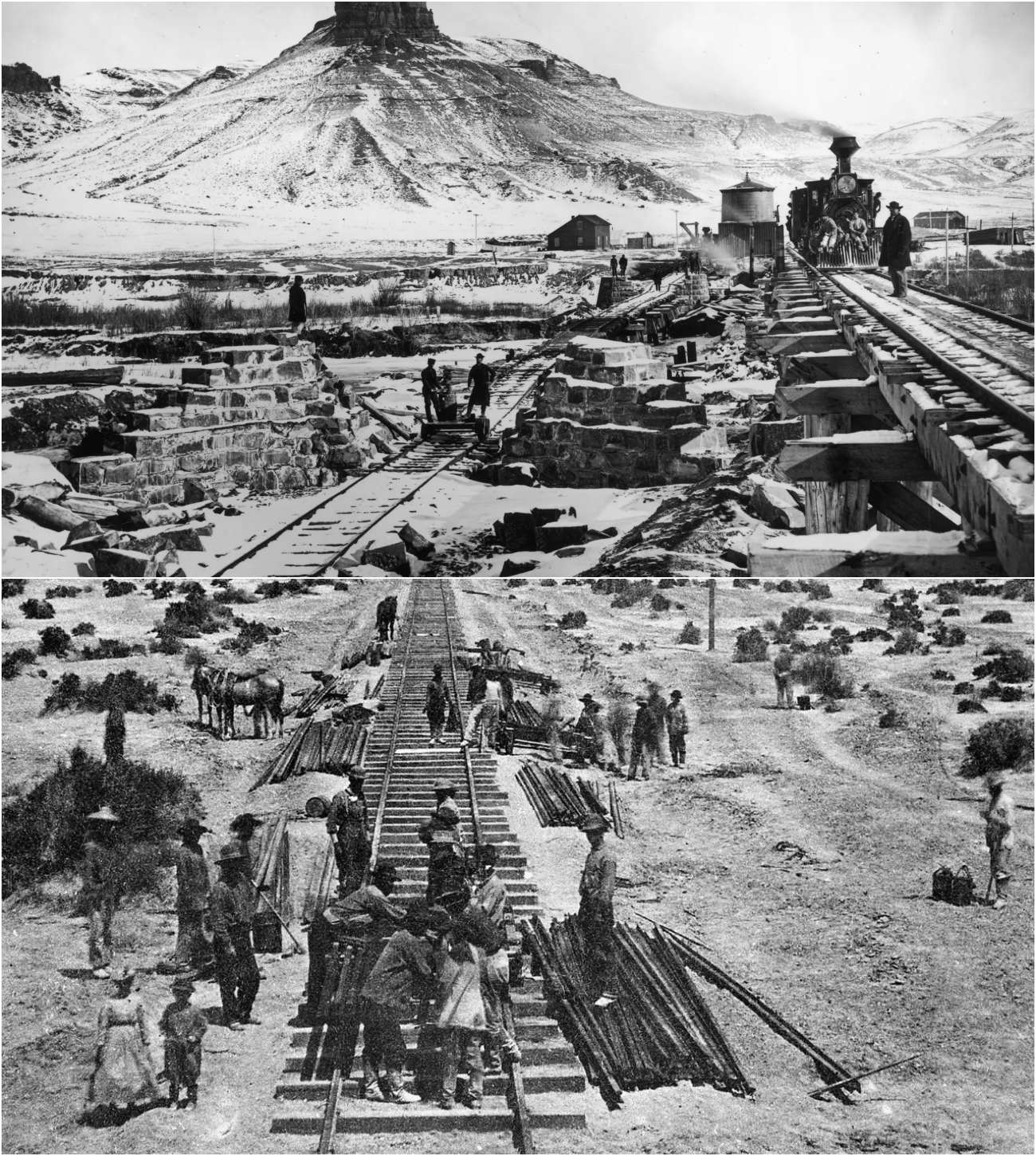

The photographs from the era—though fragmentary and incomplete—show the scale of the work. Images of Chinese workers standing in a tunnel holding drills and hammers, their faces obscured by shadow and the limitations of early photography; pictures of grading crews, dozens of men with shovels working a hillside; shots of the trestles under construction, massive timber frameworks rising out of canyons, dwarfing the men who built them.

These images do not show the deaths, the suffering, the cold, the heat, or the exhaustion, but they show the men. And that is something. The engineers who designed the transcontinental railroad are remembered—Theodore Judah, Grenville Dodge. Their names are on plaques and monuments. The investors, the Big Four—Leland Stanford, Collis Potter Huntington, Mark Hopkins, Charles Crocker—made fortunes and founded universities, their names on buildings across California.

But the workers, the men who did the actual building, are mostly forgotten. In 2014, the U.S. Department of Labor inducted the Chinese railroad workers into the Labor Hall of Honor, placing a plaque and making speeches. But for over a century, their contributions were erased.

Historians are working to recover their stories through oral histories from descendants, company records that are fragmentary and incomplete, and archaeological work at old campsites that uncover artifacts, tools, and personal items. Slowly, the picture is being filled in, but much is lost. The workers themselves, the ones who survived, rarely spoke about their experiences. It was just work—hard, dangerous work. You did it, you survived, and you moved on. There was no expectation of recognition or gratitude, and for over a century, there was none.

The transcontinental railroad is still in use today. The route has been modified, tunnels improved, and grades eased. But the bones of the original line are still there. Freight trains carrying goods from the ports of California to the markets of the East still follow the path carved out by Chinese and Irish laborers in the 1860s.

The infrastructure they built has been carrying commerce for over 150 years, and it was constructed almost entirely by hand. The tools used to build the transcontinental railroad were simple: shovels, pickaxes, sledgehammers, wheelbarrows, hand drills, and black powder. No steam shovels, no mechanical excavators. Everything—every cubic yard of dirt moved, every foot of tunnel blasted, every rail spike driven—was done by human muscle.

The scale is staggering. Over 20 million cubic yards of earth were moved during the construction of the Central Pacific line alone. That’s enough to fill a trench 10 feet deep and 10 feet wide from San Francisco to New York, and it was moved one shovel full at a time.

The engineering challenges were solved with ingenuity and brute force. The trestles—wooden bridges that carried the tracks over canyons and ravines—were built using timber hauled from hundreds of miles away. The trestles were massive structures, some over 100 feet high, built on slopes where a misplaced timber could send the whole structure collapsing.

The Chinese workers excelled at this, building trestles that were architectural marvels using mortise and tenon joints, wooden pegs, and hand-cut timbers. Many of these trestles were later replaced with stone or steel, but some of the original wooden structures stood for decades.

The Summit Tunnel, the longest and most difficult tunnel on the Central Pacific line, was finally completed in November 1867 after two years of continuous work. When the final blast broke through, connecting the east and west faces, the alignment was nearly perfect. The two bores, started from opposite sides of the mountain and guided only by surveying and mathematics, met with less than two inches of error over 1,659 feet. It was a triumph of engineering, built by men working with hand drills and black powder.

The human cost of that triumph was written in bodies. The Central Pacific estimated that over 1,000 Chinese workers died during the construction of the line—one death for roughly every mile of track. The Union Pacific’s toll was lower, estimated at 400 to 500, but still significant. These were not random accidents; they resulted from pushing men to work faster than was safe in conditions that were inherently dangerous, with no safety equipment and no oversight.

The companies knew men would die. They accepted it as a cost of doing business. The workers had no choice. For the Chinese immigrants, the railroad was one of the few employers willing to hire them. Anti-Chinese sentiment was pervasive in California. They were excluded from most trades, barred from testifying in court, and subject to violence and discrimination. The railroad offered wages, however meager, and the possibility of survival.

For the Irish workers on the Union Pacific, the situation was similar. Fleeing famine and prejudice, they took the work because there was nothing else. The freed slaves who worked on the line were escaping the sharecropping system of the post-Civil War South. The railroad was brutal, but it paid cash. And for men with no other options, that was enough.

#### A Complicated Legacy

The legacy of the transcontinental railroad is complicated. It was an engineering marvel that transformed the economy, enabled the growth of cities, expanded agriculture, and facilitated the industrialization of the West. But it was also built on exploitation, on the labor of men who were treated as disposable, and on the destruction of Native American lands and ways of life.

The railroad brought settlers who displaced the tribes and buffalo hunters who slaughtered the herds to near extinction. The tribes knew what the railroad meant, and they fought it. They lost. The physical remnants of the construction are still visible today. In the Sierra Nevada, you can hike to the sites of the old tunnels—some still in use, widened and reinforced, carrying modern freight. Others are abandoned, sealed off, slowly being reclaimed by the mountains.

The roadbed, the graded shelf cut into the hillsides, is still there, overgrown with trees and brush but recognizable to anyone who knows what to look for. The retaining walls built by Chinese workers 150 years ago still stand, stones fitted so precisely that they haven’t shifted. In Nevada and Utah, the old grade is visible from the air—a scar running across the desert, parallel to the modern tracks.

Scattered along the line are the graves—small markers and forgotten cemeteries, piles of stones in the desert, places where workers were buried where they fell and never moved. Some of these graves have been located and documented by historians and archaeologists, but many remain lost.

The photographs from the era—though fragmentary and incomplete—show the scale of the work. Images of Chinese workers standing in a tunnel holding drills and hammers, their faces obscured by shadow and the limitations of early photography; pictures of grading crews, dozens of men with shovels working a hillside; shots of the trestles under construction, massive timber frameworks rising out of canyons, dwarfing the men who built them.

These images do not show the deaths, the suffering, the cold, the heat, or the exhaustion, but they show the men. And that is something. The engineers who designed the transcontinental railroad are remembered—Theodore Judah, Grenville Dodge. Their names are on plaques and monuments. The investors, the Big Four—Leland Stanford, Collis Potter Huntington, Mark Hopkins, Charles Crocker—made fortunes and founded universities, their names on buildings across California.

But the workers, the men who did the actual building, are mostly forgotten. In 2014, the U.S. Department of Labor inducted the Chinese railroad workers into the Labor Hall of Honor, placing a plaque and making speeches. But for over a century, their contributions were erased.

Historians are working to recover their stories through oral histories from descendants, company records that are fragmentary and incomplete, and archaeological work at old campsites that uncover artifacts, tools, and personal items. Slowly, the picture is being filled in, but much is lost. The workers themselves, the ones who survived, rarely spoke about their experiences. It was just work—hard, dangerous work. You did it, you survived, and you moved on. There was no expectation of recognition or gratitude, and for over a century, there was none.

The transcontinental railroad is still in use today. The route has been modified, tunnels improved, and grades eased. But the bones of the original line are still there. Freight trains carrying goods from the ports of California to the markets of the East still follow the path carved out by Chinese and Irish laborers in the 1860s.

The infrastructure they built has been carrying commerce for over 150 years, and it was constructed almost entirely by hand. The tools used to build the transcontinental railroad were simple: shovels, pickaxes, sledgehammers, wheelbarrows, hand drills, and black powder. No steam shovels, no mechanical excavators. Everything—every cubic yard of dirt moved, every foot of tunnel blasted, every rail spike driven—was done by human muscle.

The scale is staggering. Over 20 million cubic yards of earth were moved during the construction of the Central Pacific line alone. That’s enough to fill a trench 10 feet deep and 10 feet wide from San Francisco to New York, and it was moved one shovel full at a time.

The engineering challenges were solved with ingenuity and brute force. The trestles—wooden bridges that carried the tracks over canyons and ravines—were built using timber hauled from hundreds of miles away. The trestles were massive structures, some over 100 feet high, built on slopes where a misplaced timber could send the whole structure collapsing.

The Chinese workers excelled at this, building trestles that were architectural marvels using mortise and tenon joints, wooden pegs, and hand-cut timbers. Many of these trestles were later replaced with stone or steel, but some of the original wooden structures stood for decades.

The Summit Tunnel, the longest and most difficult tunnel on the Central Pacific line, was finally completed in November 1867 after two years of continuous work. When the final blast broke through, connecting the east and west faces, the alignment was nearly perfect. The two bores, started from opposite sides of the mountain and guided only by surveying and mathematics, met with less than two inches of error over 1,659 feet. It was a triumph of engineering, built by men working with hand drills and black powder.

The human cost of that triumph was written in bodies. The Central Pacific estimated that over 1,000 Chinese workers died during the construction of the line—one death for roughly every mile of track. The Union Pacific’s toll was lower, estimated at 400 to 500, but still significant. These were not random accidents; they resulted from pushing men to work faster than was safe in conditions that were inherently dangerous, with no safety equipment and no oversight.

The companies knew men would die. They accepted it as a cost of doing business. The workers had no choice. For the Chinese immigrants, the railroad was one of the few employers willing to hire them. Anti-Chinese sentiment was pervasive in California. They were excluded from most trades, barred from testifying in court, and subject to violence and discrimination. The railroad offered wages, however meager, and the possibility of survival.

For the Irish workers on the Union Pacific, the situation was similar. Fleeing famine and prejudice, they took the work because there was nothing else. The freed slaves who worked on the line were escaping the sharecropping system of the post-Civil War South. The railroad was brutal, but it paid cash. And for men with no other options, that was enough.

#### A Complicated Legacy

The legacy of the transcontinental railroad is complicated. It was an engineering marvel that transformed the economy, enabled the growth of cities, expanded agriculture, and facilitated the industrialization of the West. But it was also built on exploitation, on the labor of men who were treated as disposable, and on the destruction of Native American lands and ways of life.

The railroad brought settlers who displaced the tribes and buffalo hunters who slaughtered the herds to near extinction. The tribes knew what the railroad meant, and they fought it. They lost. The physical remnants of the construction are still visible today. In the Sierra Nevada, you can hike to the sites of the old tunnels—some still in use, widened and reinforced, carrying modern freight. Others are abandoned, sealed off, slowly being reclaimed by the mountains.

The roadbed, the graded shelf cut into the hillsides, is still there, overgrown with trees and brush but recognizable to anyone who knows what to look for. The retaining walls built by Chinese workers 150 years ago still stand, stones fitted so precisely that they haven’t shifted. In Nevada and Utah, the old grade is visible from the air—a scar running across the desert, parallel to the modern tracks.

Scattered along the line are the graves—small markers and forgotten cemeteries, piles of stones in the desert, places where workers were buried where they fell and never moved. Some of these graves have been located and documented by historians and archaeologists, but many remain lost.

The photographs from the era—though fragmentary and incomplete—show the scale of the work. Images of Chinese workers standing in a tunnel holding drills and hammers, their faces obscured by shadow and the limitations of early photography; pictures of grading crews, dozens of men with shovels working a hillside; shots of the trestles under construction, massive timber frameworks rising out of canyons, dwarfing the men who built them.

These images do not show the deaths, the suffering, the cold, the heat, or the exhaustion, but they show the men. And that is something. The engineers who designed the transcontinental railroad are remembered—Theodore Judah, Grenville Dodge. Their names are on plaques and monuments. The investors, the Big Four—Leland Stanford, Collis Potter Huntington, Mark Hopkins, Charles Crocker—made fortunes and founded universities, their names on buildings across California.

But the workers, the men who did the actual building, are mostly forgotten. In 2014, the U.S. Department of Labor inducted the Chinese railroad workers into the Labor Hall of Honor, placing a plaque and making speeches. But for over a century, their contributions were erased.

Historians are working to recover their stories through oral histories from descendants, company records that are fragmentary and incomplete, and archaeological work at old campsites that uncover artifacts, tools, and personal items. Slowly, the picture is being filled in, but much is lost. The workers themselves, the ones who survived, rarely spoke about their experiences. It was just work—hard, dangerous work. You did it, you survived, and you moved on. There was no expectation of recognition or gratitude, and for over a century, there was none.

The transcontinental railroad is still in use today. The route has been modified, tunnels improved, and grades eased. But the bones of the original line are still there. Freight trains carrying goods from the ports of California to the markets of the East still follow the path carved out by Chinese and Irish laborers in the 1860s.

The infrastructure they built has been carrying commerce for over 150 years, and it was constructed almost entirely by hand. The tools used to build the transcontinental railroad were simple: shovels, pickaxes, sledgehammers, wheelbarrows, hand drills, and black powder. No steam shovels, no mechanical excavators. Everything—every cubic yard of dirt moved, every foot of tunnel blasted, every rail spike driven—was done by human muscle.

The scale is staggering. Over 20 million cubic yards of earth were moved during the construction of the Central Pacific line alone. That’s enough to fill a trench 10 feet deep and 10 feet wide from San Francisco to New York, and it was moved one shovel full at a time.

The engineering challenges were solved with ingenuity and brute force. The trestles—wooden bridges that carried the tracks over canyons and ravines—were built using timber hauled from hundreds of miles away. The trestles were massive structures, some over 100 feet high, built on slopes where a misplaced timber could send the whole structure collapsing.

The Chinese workers excelled at this, building trestles that were architectural marvels using mortise and tenon joints, wooden pegs, and hand-cut timbers. Many of these trestles were later replaced with stone or steel, but some of the original wooden structures stood for decades.

The Summit Tunnel, the longest and most difficult tunnel on the Central Pacific line, was finally completed in November 1867 after two years of continuous work. When the final blast broke through, connecting the east and west faces, the alignment was nearly perfect. The two bores, started from opposite sides of the mountain and guided only by surveying and mathematics, met with less than two inches of error over 1,659 feet. It was a triumph of engineering, built by men working with hand drills and black powder.

The human cost of that triumph was written in bodies. The Central Pacific estimated that over 1,000 Chinese workers died during the construction of the line—one death for roughly every mile of track. The Union Pacific’s toll was lower, estimated at 400 to 500, but still significant. These were not random accidents; they resulted from pushing men to work faster than was safe in conditions that were inherently dangerous, with no safety equipment and no oversight.

The companies knew men would die. They accepted it as a cost of doing business. The workers had no choice. For the Chinese immigrants, the railroad was one of the few employers willing to hire them. Anti-Chinese sentiment was pervasive in California. They were excluded from most trades, barred from testifying in court, and subject to violence and discrimination. The railroad offered wages, however meager, and the possibility of survival.

For the Irish workers on the Union Pacific, the situation was similar. Fleeing famine and prejudice, they took the work because there was nothing else. The freed slaves who worked on the line were escaping the sharecropping system of the post-Civil War South. The railroad was brutal, but it paid cash. And for men with no other options, that was enough.

#### A Complicated Legacy

The legacy of the transcontinental railroad is complicated. It was an engineering marvel that transformed the economy, enabled the growth of cities, expanded agriculture, and facilitated the industrialization of the West. But it was also built on exploitation, on the labor of men who were treated as disposable, and on the destruction of Native American lands and ways of life.

The railroad brought settlers who displaced the tribes and buffalo hunters who slaughtered the herds to near extinction. The tribes knew what the railroad meant, and they fought it. They lost. The physical remnants of the construction are still visible today. In the Sierra Nevada, you can hike to the sites of the old tunnels—some still in use, widened and reinforced, carrying modern freight. Others are abandoned, sealed off, slowly being reclaimed by the mountains.

The roadbed, the graded shelf cut into the hillsides, is still there, overgrown with trees and brush but recognizable to anyone who knows what to look for. The retaining walls built by Chinese workers 150 years ago still stand, stones fitted so precisely that they haven’t shifted. In Nevada and Utah, the old grade is visible from the air—a scar running across the desert, parallel to the modern tracks.

Scattered along the line are the graves—small markers and forgotten cemeteries, piles of stones in the desert, places where workers were buried where they fell and never moved. Some of these graves have been located and documented by historians and archaeologists, but many remain lost.

The photographs from the era—though fragmentary and incomplete—show the scale of the work. Images of Chinese workers standing in a tunnel holding drills and hammers, their faces obscured by shadow and the limitations of early photography; pictures of grading crews, dozens of men with shovels working a hillside; shots of the trestles under construction, massive timber frameworks rising out of canyons, dwarfing the men who built them.

These images do not show the deaths, the suffering, the cold, the heat, or the exhaustion, but they show the men. And that is something. The engineers who designed the transcontinental railroad are remembered—Theodore Judah, Grenville Dodge. Their names are on plaques and monuments. The investors, the Big Four—Leland Stanford, Collis Potter Huntington, Mark Hopkins, Charles Crocker—made fortunes and founded universities, their names on buildings across California.

But the workers, the men who did the actual building, are mostly forgotten. In 2014, the U.S. Department of Labor inducted the Chinese railroad workers into the Labor Hall of Honor, placing a plaque and making speeches. But for over a century, their contributions were erased.

Historians are working to recover their stories through oral histories from descendants, company records that are fragmentary and incomplete, and archaeological work at old campsites that uncover artifacts, tools, and personal items. Slowly, the picture is being filled in, but much is lost. The workers themselves, the ones who survived, rarely spoke about their experiences. It was just work—hard, dangerous work. You did it, you survived, and you moved on. There was no expectation of recognition or gratitude, and for over a century, there was none.

The transcontinental railroad is still in use today. The route has been modified, tunnels improved, and grades eased. But the bones of the original line are still there. Freight trains carrying goods from the ports of California to the markets of the East still follow the path carved out by Chinese and Irish laborers in the 1860s.

The infrastructure they built has been carrying commerce for over 150 years, and it was constructed almost entirely by hand. The tools used to build the transcontinental railroad were simple: shovels, pickaxes, sledgehammers, wheelbarrows, hand drills, and black powder. No steam shovels, no mechanical excavators. Everything—every cubic yard of dirt moved, every foot of tunnel blasted, every rail spike driven—was done by human muscle.

The scale is staggering. Over 20 million cubic yards of earth were moved during the construction of the Central Pacific line alone. That’s enough to fill a trench 10 feet deep and 10 feet wide from San Francisco to New York, and it was moved one shovel full at a time.

The engineering challenges were solved with ingenuity and brute force. The trestles—wooden bridges that carried the tracks over canyons and ravines—were built using timber hauled from hundreds of miles away. The trestles were massive structures, some over 100 feet high, built on slopes where a misplaced timber could send the whole structure collapsing.

The Chinese workers excelled at this, building trestles that were architectural marvels using mortise and tenon joints, wooden pegs, and hand-cut timbers. Many of these trestles were later replaced with stone or steel, but some of the original wooden structures stood for decades.

The Summit Tunnel, the longest and most difficult tunnel on the Central Pacific line, was finally completed in November 1867 after two years of continuous work. When the final blast broke through, connecting the east and west faces, the alignment was nearly perfect. The two bores, started from opposite sides of the mountain and guided only by surveying and mathematics, met with less than two inches of error over 1,659 feet. It was a triumph of engineering, built by men working with hand drills and black powder.

The human cost of that triumph was written in bodies. The Central Pacific estimated that over 1,000 Chinese workers died during the construction of the line—one death for roughly every mile of track. The Union Pacific’s toll was lower, estimated at 400 to 500, but still significant. These were not random accidents; they resulted from pushing men to work faster than was safe in conditions that were inherently dangerous, with no safety equipment and no oversight.

The companies knew men would die. They accepted it as a cost of doing business. The workers had no choice. For the Chinese immigrants, the railroad was one of the few employers willing to hire them. Anti-Chinese sentiment was pervasive in California. They were excluded from most trades, barred from testifying in court, and subject to violence and discrimination. The railroad offered wages, however meager, and the possibility of survival.

For the Irish workers on the Union Pacific, the situation was similar. Fleeing famine and prejudice, they took the work because there was nothing else. The freed slaves who worked on the line were escaping the sharecropping system of the post-Civil War South. The railroad was brutal, but it paid cash. And for men with no other options, that was enough.

#### A Complicated Legacy

The legacy of the transcontinental railroad is complicated. It was an engineering marvel that transformed the economy, enabled the growth of cities, expanded agriculture, and facilitated the industrialization of the West. But it was also built on exploitation, on the labor of men who were treated as disposable, and on the destruction of Native American lands and ways of life.

The railroad brought settlers who displaced the tribes and buffalo hunters who slaughtered the herds to near extinction. The tribes knew what the railroad meant, and they fought it. They lost. The physical remnants of the construction are still visible today. In the Sierra Nevada, you can hike to the sites of the old tunnels—some still in use, widened and reinforced, carrying modern freight. Others are abandoned, sealed off, slowly being reclaimed by the mountains.

The roadbed, the graded shelf cut into the hillsides, is still there, overgrown with trees and brush but recognizable to anyone who knows what to look for. The retaining walls built by Chinese workers 150 years ago still stand, stones fitted so precisely that they haven’t shifted. In Nevada and Utah, the old grade is visible from the air—a scar running across the desert, parallel to the modern tracks.

Scattered along the line are the graves—small markers and forgotten cemeteries, piles of stones in the desert, places where workers were buried where they fell and never moved. Some of these graves have been located and documented by historians and archaeologists, but many remain lost.

The photographs from the era—though fragmentary and incomplete—show the scale of the work. Images of Chinese workers standing in a tunnel holding drills and hammers, their faces obscured by shadow and the limitations of early photography; pictures of grading crews, dozens of men with shovels working a hillside; shots of the trestles under construction, massive timber frameworks rising out of canyons, dwarfing the men who built them.

These images do not show the deaths, the suffering, the cold, the heat, or the exhaustion, but they show the men. And that is something. The engineers who designed the transcontinental railroad are remembered—Theodore Judah, Grenville Dodge. Their names are on plaques and monuments. The investors, the Big Four—Leland Stanford, Collis Potter Huntington, Mark Hopkins, Charles Crocker—made fortunes and founded universities, their names on buildings across California.

But the workers, the men who did the actual building, are mostly forgotten. In 2014, the U.S. Department of Labor inducted the Chinese railroad workers into the Labor Hall of Honor, placing a plaque and making speeches. But for over a century, their contributions were erased.

Historians are working to recover their stories through oral histories from descendants, company records that are fragmentary and incomplete, and archaeological work at old campsites that uncover artifacts, tools, and personal items. Slowly, the picture is being filled in, but much is lost. The workers themselves, the ones who survived, rarely spoke about their experiences. It was just work—hard, dangerous work. You did it, you survived, and you moved on. There was no expectation of recognition or gratitude, and for over a century, there was none.

The transcontinental railroad is still in use today. The route has been modified, tunnels improved, and grades eased. But the bones of the original line are still there. Freight trains carrying goods from the ports of California to the markets of the East still follow the path carved out by Chinese and Irish laborers in the 1860s.

The infrastructure they built has been carrying commerce for over 150 years, and it was constructed almost entirely by hand. The tools used to build the transcontinental railroad were simple: shovels, pickaxes, sledgehammers, wheelbarrows, hand drills, and black powder. No steam shovels, no mechanical excavators. Everything—every cubic yard of dirt moved, every foot of tunnel blasted, every rail spike driven—was done by human muscle.

The scale is staggering. Over 20 million cubic yards of earth were moved during the construction of the Central Pacific line alone. That’s enough to fill a trench 10 feet deep and 10 feet wide from San Francisco to New York, and it was moved one shovel full at a time.

The engineering challenges were solved with ingenuity and brute force. The trestles—wooden bridges that carried the tracks over canyons and ravines—were built using timber hauled from hundreds of miles away. The trestles were massive structures, some over 100 feet high, built on slopes where a misplaced timber could send the whole structure collapsing.

The Chinese workers excelled at this, building trestles that were architectural marvels using mortise and tenon joints, wooden pegs, and hand-cut timbers. Many of these trestles were later replaced with stone or steel, but some of the original wooden structures stood for decades.

The Summit Tunnel, the longest and most difficult tunnel on the Central Pacific line, was finally completed in November 1867 after two years of continuous work. When the final blast broke through, connecting the east and west faces, the alignment was nearly perfect. The two bores, started from opposite sides of the mountain and guided only by surveying and mathematics, met with less than two inches of error over 1,659 feet. It was a triumph of engineering, built by men working with hand drills and black powder.

The human cost of that triumph was written in bodies. The Central Pacific estimated that over 1,000 Chinese workers died during the construction of the line—one death for roughly every mile of track. The Union Pacific’s toll was lower, estimated at 400 to 500, but still significant. These were not random accidents; they resulted from pushing men to work faster than was safe in conditions that were inherently dangerous, with no safety equipment and no oversight.

The companies knew men would die. They accepted it as a cost of doing business. The workers had no choice. For the Chinese immigrants, the railroad was one of the few employers willing to hire them. Anti-Chinese sentiment was pervasive in California. They were excluded from most trades, barred from testifying in court, and subject to violence and discrimination. The railroad offered wages, however meager, and the possibility of survival.

For the Irish workers on the Union Pacific, the situation was similar. Fleeing famine and prejudice, they took the work because there was nothing else. The freed slaves who worked on the line were escaping the sharecropping system of the post-Civil War South. The railroad was brutal, but it paid cash. And for men with no other options, that was enough.

#### A Complicated Legacy

The legacy of the transcontinental railroad is complicated. It was an engineering marvel that transformed the economy, enabled the growth of cities, expanded agriculture, and facilitated the industrialization of the West. But it was also built on exploitation, on the labor of men who were treated as disposable, and on the destruction of Native American lands and ways of life.

The railroad brought settlers who displaced the tribes and buffalo hunters who slaughtered the herds to near extinction. The tribes knew what the railroad meant, and they fought it. They lost. The physical remnants of the construction are still visible today. In the Sierra Nevada, you can hike to the sites of the old tunnels—some still in use, widened and reinforced, carrying modern freight. Others are abandoned, sealed off, slowly being reclaimed by the mountains.

The roadbed, the graded shelf cut into the hillsides, is still there, overgrown with trees and brush but recognizable to anyone who knows what to look for. The retaining walls built by Chinese workers 150 years ago still stand, stones fitted so precisely that they haven’t shifted. In Nevada and Utah, the old grade is visible from the air—a scar running across the desert, parallel to the modern tracks.

Scattered along the line are the graves—small markers and forgotten cemeteries, piles of stones in the desert, places where workers were buried where they fell and never moved. Some of these graves have been located and documented by historians and archaeologists, but many remain lost.

The photographs from the era—though fragmentary and incomplete—show the scale of the work. Images of Chinese workers standing in a tunnel holding drills and hammers, their faces obscured by shadow and the limitations of early photography; pictures of grading crews, dozens of men with shovels working a hillside; shots of the trestles under construction, massive timber frameworks rising out of canyons, dwarfing the men who built them.

These images do not show the deaths, the suffering, the cold, the heat, or the exhaustion, but they show the men. And that is something. The engineers who designed the transcontinental railroad are remembered—Theodore Judah, Grenville Dodge. Their names are on plaques and monuments. The investors, the Big Four—Leland Stanford, Collis Potter Huntington, Mark Hopkins, Charles Crocker—made fortunes and founded universities, their names on buildings across California.

But the workers, the men who did the actual building, are mostly forgotten. In 2014, the U.S. Department of Labor inducted the Chinese railroad workers into the Labor Hall of Honor, placing a plaque and making speeches. But for over a century, their contributions were erased.

Historians are working to recover their stories through oral histories from descendants, company records that are fragmentary and incomplete, and archaeological work at old campsites that uncover artifacts, tools, and personal items. Slowly, the picture is being filled in, but much is lost. The workers themselves, the ones who survived, rarely spoke about their experiences. It was just work—hard, dangerous work. You did it, you survived, and you moved on. There was no expectation of recognition or gratitude, and for over a century, there was none.

The transcontinental railroad is still in use today. The route has been modified, tunnels improved, and grades eased. But the bones of the original line are still there. Freight trains carrying goods from the ports of California to the markets of the East still follow the path carved out by Chinese and Irish laborers in the 1860s.

The infrastructure they built has been carrying commerce for over 150 years, and it was constructed almost entirely by hand. The tools used to build the transcontinental railroad were simple: shovels, pickaxes, sledgehammers, wheelbarrows, hand drills, and black powder. No steam shovels, no mechanical excavators. Everything—every cubic yard of dirt moved, every foot of tunnel blasted, every rail spike driven—was done by human muscle.

The scale is staggering. Over 20 million cubic yards of earth were moved during the construction of the Central Pacific line alone. That’s enough to fill a trench 10 feet deep and 10 feet wide from San Francisco to New York, and it was moved one shovel full at a time.

The engineering challenges were solved with ingenuity and brute force. The trestles—wooden bridges that carried the tracks over canyons and ravines—were built using timber hauled from hundreds of miles away. The trestles were massive structures, some over 100 feet high, built on slopes where a misplaced timber could send the whole structure collapsing.

The Chinese workers excelled at this, building trestles that were architectural marvels using mortise and tenon joints, wooden pegs, and hand-cut timbers. Many of these trestles were later replaced with stone or steel, but some of the original wooden structures stood for decades.

The Summit Tunnel, the longest and most difficult tunnel on the Central Pacific line, was finally completed in November 1867 after two years of continuous work. When the final blast broke through, connecting the east and west faces, the alignment was nearly perfect. The two bores, started from opposite sides of the mountain and guided only by surveying and mathematics, met with less than two inches of error over 1,659 feet. It was a triumph of engineering, built by men working with hand drills and black powder.

The human cost of that triumph was written in bodies. The Central Pacific estimated that over 1,000 Chinese workers died during the construction of the line—one death for roughly every mile of track. The Union Pacific’s toll was lower, estimated at 400 to 500, but still significant. These were not random accidents; they resulted from pushing men to work faster than was safe in conditions that were inherently dangerous, with no safety equipment and no oversight.

The companies knew men would die. They accepted it as a cost of doing business. The workers had no choice. For the Chinese immigrants, the railroad was one of the few employers willing to hire them. Anti-Chinese sentiment was pervasive in California. They were excluded from most trades, barred from testifying in court, and subject to violence and discrimination. The railroad offered wages, however meager, and the possibility of survival.

For the Irish workers on the Union Pacific, the situation was similar. Fleeing famine and prejudice, they took the work because there was nothing else. The freed slaves who worked on the line were escaping the sharecropping system of the post-Civil War South. The railroad was brutal, but it paid cash. And for men with no other options, that was enough.

#### A Complicated Legacy

The legacy of the transcontinental railroad is complicated. It was an engineering marvel that transformed the economy, enabled the growth of cities, expanded agriculture, and facilitated the industrialization of the West. But it was also built on exploitation, on the labor of men who were treated as disposable, and on the destruction of Native American lands and ways of life.

The railroad brought settlers who displaced the tribes and buffalo hunters who slaughtered the herds to near extinction. The tribes knew what the railroad meant, and they fought it. They lost. The physical remnants of the construction are still visible today. In the Sierra Nevada, you can hike to the sites of the old tunnels—some still in use, widened and reinforced, carrying modern freight. Others are abandoned, sealed off, slowly being reclaimed by the mountains.

The roadbed, the graded shelf cut into the hillsides, is still there, overgrown with trees and brush but recognizable to anyone who knows what to look for. The retaining walls built by Chinese workers 150 years ago still stand, stones fitted so precisely that they haven’t shifted. In Nevada and Utah, the old grade is visible from the air—a scar running across the desert, parallel to the modern tracks.

Scattered along the line are the graves—small markers and forgotten cemeteries, piles of stones in the desert, places where workers were buried where they fell and never moved. Some of these graves have been located and documented by historians and archaeologists, but many remain lost.

The photographs from the era—though fragmentary and incomplete—show the scale of the work. Images of Chinese workers standing in a tunnel holding drills and hammers, their faces obscured by shadow and the limitations of early photography; pictures of grading crews, dozens of men with shovels working a hillside; shots of the trestles under construction, massive timber frameworks rising out of canyons, dwarfing the men who built them.

These images do not show the deaths, the suffering, the cold, the heat, or the exhaustion, but they show the men. And that is something. The engineers who designed the transcontinental railroad are remembered—Theodore Judah, Grenville Dodge. Their names are on plaques and monuments. The investors, the Big Four—Leland Stanford, Collis Potter Huntington, Mark Hopkins, Charles Crocker—made fortunes and founded universities, their names on buildings across California.

But the workers, the men who did the actual building, are mostly forgotten. In 2014, the U.S. Department of Labor inducted the Chinese railroad workers into the Labor Hall of Honor, placing a plaque and making speeches. But for over a century, their contributions were erased.

Historians are working to recover their stories through oral histories from descendants, company records that are fragmentary and incomplete, and archaeological work at old campsites that uncover artifacts, tools, and personal items. Slowly, the picture is being filled in, but much is lost. The workers themselves, the ones who survived, rarely spoke about their experiences. It was just work—hard, dangerous work. You did it, you survived, and you moved on. There was no expectation of recognition or gratitude, and for over a century, there was none.

The transcontinental railroad is still in use today. The route has been modified, tunnels improved, and grades eased. But the bones of the original line are still there. Freight trains carrying goods from the ports of California to the markets of the East still follow the path carved out by Chinese and Irish laborers in the 1860s.

The infrastructure they built has been carrying commerce for over 150 years, and it was constructed almost entirely by hand. The tools used to build the transcontinental railroad were simple: shovels, pickaxes, sledgehammers, wheelbarrows, hand drills, and black powder. No steam shovels, no mechanical excavators. Everything—every cubic yard of dirt moved, every foot of tunnel blasted, every rail spike driven—was done by human muscle.

The scale is staggering. Over 20 million cubic yards of earth were moved during the construction of the Central Pacific line alone. That’s enough to fill a trench 10 feet deep and 10 feet wide from San Francisco to New York, and it was moved one shovel full at a time.

The engineering challenges were solved with ingenuity and brute force. The trestles—wooden bridges that carried the tracks over canyons and ravines—were built using timber hauled from hundreds of miles away. The trestles were massive structures, some over 100 feet high, built on slopes where a misplaced timber could send the whole structure collapsing.

The Chinese workers excelled at this, building trestles that were architectural marvels using mortise and tenon joints, wooden pegs, and hand-cut timbers. Many of these trestles were later replaced with stone or steel, but some of the original wooden structures stood for decades.

The Summit Tunnel, the longest and most difficult tunnel on the Central Pacific line, was finally completed in November 1867 after two years of continuous work. When the final blast broke through, connecting the east and west faces, the alignment was nearly perfect. The two bores, started from opposite sides of the mountain and guided only by surveying and mathematics, met with less than two inches of error over 1,659 feet. It was a triumph of engineering, built by men working with hand drills and black powder.

The human cost of that triumph was written in bodies. The Central Pacific estimated that over 1,000 Chinese workers died during the construction of the line—one death for roughly every mile of track. The Union Pacific’s toll was lower, estimated at 400 to 500, but still significant. These were not random accidents; they resulted from pushing men to work faster than was safe in conditions that were inherently dangerous, with no safety equipment and no oversight.

The companies knew men would die. They accepted it as a cost of doing business. The workers had no choice. For the Chinese immigrants, the railroad was one of the few employers willing to hire them. Anti-Chinese sentiment was pervasive in California. They were excluded from most trades, barred from testifying in court, and subject to violence and discrimination. The railroad offered wages, however meager, and the possibility of survival.

For the Irish workers on the Union Pacific, the situation was similar. Fleeing famine and prejudice, they took the work because there was nothing else. The freed slaves who worked on the line were escaping the sharecropping system of the post-Civil War South. The railroad was brutal, but it paid cash. And for men with no other options, that was enough.

#### A Complicated Legacy

The legacy of the transcontinental railroad is complicated. It was an engineering marvel that transformed the economy, enabled the growth of cities, expanded agriculture, and facilitated the industrialization of the West. But it was also built on exploitation, on the labor of men who were treated as disposable, and on the destruction of Native American lands and ways of life.

The railroad brought settlers who displaced the tribes and buffalo hunters who slaughtered the herds to near extinction. The tribes knew what the railroad meant, and they fought it. They lost. The physical remnants of the construction are still visible today. In the Sierra Nevada, you can hike to the sites of the old tunnels—some still in use, widened and reinforced, carrying modern freight. Others are abandoned, sealed off, slowly being reclaimed by the mountains.

The roadbed, the graded shelf cut into the hillsides, is still there, overgrown with trees and brush but recognizable to anyone who knows what to look for. The retaining walls built by Chinese workers 150 years ago still stand, stones fitted so precisely that they haven’t shifted. In Nevada and Utah, the old grade is visible from the air—a scar running across the desert, parallel to the modern tracks.

Scattered along the line are the graves—small markers and forgotten cemeteries, piles of stones in the desert, places where workers were buried where they fell and never moved. Some of these graves have been located and documented by historians and archaeologists, but many remain lost.

The photographs from the era—though fragmentary and incomplete—show the scale of the work. Images of Chinese workers standing in a tunnel holding drills and hammers, their faces obscured by shadow and the limitations of early photography; pictures of grading crews, dozens of men with shovels working a hillside; shots of the trestles under construction, massive timber frameworks rising out of canyons, dwarfing the men who built them.

These images do not show the deaths, the suffering, the cold, the heat, or the exhaustion, but they show the men. And that is something. The engineers who designed the transcontinental railroad are remembered—Theodore Judah, Grenville Dodge. Their names are on plaques and monuments. The investors, the Big Four—Leland Stanford, Collis Potter Huntington, Mark Hopkins, Charles Crocker—made fortunes and founded universities, their names on buildings across California.

But the workers, the men who did the actual building, are mostly forgotten. In 2014, the U.S. Department of Labor inducted the Chinese railroad workers into the Labor Hall of Honor, placing a plaque and making speeches. But for over a century, their contributions were erased.

Historians are working to recover their stories through oral histories from descendants, company records that are fragmentary and incomplete, and archaeological work at old campsites that uncover artifacts, tools, and personal items. Slowly, the picture is being filled in, but much is lost. The workers themselves, the ones who survived, rarely spoke about their experiences. It was just work—hard, dangerous work. You did it, you survived, and you moved on. There was no expectation of recognition or gratitude, and for over a century, there was none.

The transcontinental railroad is still in use today. The route has been modified, tunnels improved, and grades eased. But the bones of the original line are still there. Freight trains carrying goods from the ports of California to the markets of the East still follow the path carved out by Chinese and Irish laborers in the 1860s.

The infrastructure they built has been carrying commerce for over 150 years, and it was constructed almost entirely by hand. The tools used to build the transcontinental railroad were simple: shovels, pickaxes, sledgehammers, wheelbarrows, hand drills, and black powder. No steam shovels, no mechanical excavators. Everything—every cubic yard of dirt moved, every foot of tunnel blasted, every rail spike driven—was done by human muscle.

The scale is staggering. Over 20 million cubic yards of earth were moved during the construction of the Central Pacific line alone. That’s enough to fill a trench 10 feet deep and 10 feet wide from San Francisco to New York, and it was moved one shovel full at a time.

The engineering challenges were solved with ingenuity and brute force. The trestles—wooden bridges that carried the tracks over canyons and ravines—were built using timber hauled from hundreds of miles away. The trestles were massive structures, some over 100 feet high, built on slopes where a misplaced timber could send the whole structure collapsing.

The Chinese workers excelled at this, building trestles that were architectural marvels using mortise and tenon joints, wooden pegs, and hand-cut timbers. Many of these trestles were later replaced with stone or steel, but some of the original wooden structures stood for decades.

The Summit Tunnel, the longest and most difficult tunnel on the Central Pacific line, was finally completed in November 1867 after two years of continuous work. When the final blast broke through, connecting the east and west faces, the alignment was nearly perfect. The two bores, started from opposite sides of the mountain and guided only by surveying and mathematics, met with less than two inches of error over 1,659 feet. It was a triumph of engineering, built by men working with hand drills and black powder.

The human cost of that triumph was written in bodies. The Central Pacific estimated that over 1,000 Chinese workers died during the construction of the line—one death for roughly every mile of track. The Union Pacific’s toll was lower, estimated at 400 to 500, but still significant. These were not random accidents; they resulted from pushing men to work faster than was safe in conditions that were inherently dangerous, with no safety equipment and no oversight.

The companies knew men would die. They accepted it as a cost of doing business. The workers had no choice. For the Chinese immigrants, the railroad was one of the few employers willing to hire them. Anti-Chinese sentiment was pervasive in California. They were excluded from most trades, barred from testifying in court, and subject to violence and discrimination. The railroad offered wages, however meager, and the possibility of survival.

For the Irish workers on the Union Pacific, the situation was similar. Fleeing famine and prejudice, they took the work because there was nothing else. The freed slaves who worked on the line were escaping the sharecropping system of the post-Civil War South. The railroad was brutal, but it paid cash. And for men with no other options, that was enough.

#### A Complicated Legacy

The legacy of the transcontinental railroad is complicated. It was an engineering marvel that transformed the economy, enabled the growth of cities, expanded agriculture, and facilitated the industrialization of the West. But it was also built on exploitation, on the labor of men who were treated as disposable, and on the destruction of Native American lands and ways of life.

The railroad brought settlers who displaced the tribes and buffalo hunters who slaughtered the herds to near extinction. The tribes knew what the railroad meant, and they fought it. They lost. The physical remnants of the construction are still visible today. In the Sierra Nevada, you can hike to the sites of the old tunnels—some still in use, widened and reinforced, carrying modern freight. Others are abandoned, sealed off, slowly being reclaimed by the mountains.

The roadbed, the graded shelf cut into the hillsides, is still there, overgrown with trees and brush but recognizable to anyone who knows what to look for. The retaining walls built by Chinese workers 150 years ago still stand, stones fitted so precisely that they haven’t shifted. In Nevada and Utah, the old grade is visible from the air—a scar running across the desert, parallel to the modern tracks.

Scattered along the line are the graves—small markers and forgotten cemeteries, piles of stones in the desert, places where workers were buried where they fell and never moved. Some of these graves have been located and documented by historians and archaeologists, but many remain lost.

The photographs from the era—though fragmentary and incomplete—show the scale of the work. Images of Chinese workers standing in a tunnel holding drills and hammers, their faces obscured by shadow and the limitations of early photography; pictures of grading crews, dozens of men with shovels working a hillside; shots of the trestles under construction, massive timber frameworks rising out of canyons, dwarfing the men who built them.

These images do not show the deaths, the suffering, the cold, the heat, or the exhaustion, but they show the men. And that is something. The engineers who designed the transcontinental railroad are remembered—Theodore Judah, Grenville Dodge. Their names are on plaques and monuments. The investors, the Big Four—Leland Stanford, Collis Potter Huntington, Mark Hopkins, Charles Crocker—made fortunes and founded universities, their names on buildings across California.

But the workers, the men who did the actual building, are mostly forgotten. In 2014, the U.S. Department of Labor inducted the Chinese railroad workers into the Labor Hall of Honor, placing a plaque and making speeches. But for over a century, their contributions were erased.

Historians are working to recover their stories through oral histories from descendants, company records that are fragmentary and incomplete, and archaeological work at old campsites that uncover artifacts, tools, and personal items. Slowly, the picture is being filled in, but much is lost. The workers themselves, the ones who survived, rarely spoke about their experiences. It was just work—hard, dangerous work. You did it, you survived, and you moved on. There was no expectation of recognition or gratitude, and for over a century, there was none.

The transcontinental railroad is still in use today. The route has been modified, tunnels improved, and grades eased. But the bones of the original line are still there. Freight trains carrying goods from the ports of California to the markets of the East still follow the path carved out by Chinese and Irish laborers in the 1860s.

The infrastructure they built has been carrying commerce for over 150 years, and it was constructed almost entirely by hand. The tools used to build the transcontinental railroad were simple: shovels, pickaxes, sledgehammers, wheelbarrows, hand drills, and black powder. No steam shovels, no mechanical excavators. Everything—every cubic yard of dirt moved, every foot of tunnel blasted, every rail spike driven—was done by human muscle.

The scale is staggering. Over 20 million cubic yards of earth were moved during the construction of the Central Pacific line alone. That’s enough to fill a trench 10 feet deep and 10 feet wide from San Francisco to New York, and it was moved one shovel full at a time.

The engineering challenges were solved with ingenuity and brute force. The trestles—wooden bridges that carried the tracks over canyons and ravines—were built using timber hauled from hundreds of miles away. The trestles were massive structures, some over 100 feet high, built on slopes where a misplaced timber could send the whole structure collapsing.

The Chinese workers excelled at this, building trestles that were architectural marvels using mortise and tenon joints, wooden pegs, and hand-cut timbers. Many of these trestles were later replaced with stone or steel, but some of the original wooden structures stood for decades.

The Summit Tunnel, the longest and most difficult tunnel on the Central Pacific line, was finally completed in November 1867 after two years of continuous work. When the final blast broke through, connecting the east and west faces, the alignment was nearly perfect. The two bores, started from opposite sides of the mountain and guided only by surveying and mathematics, met with less than two inches of error over 1,659 feet. It was a triumph of engineering, built by men working with hand drills and black powder.

The human cost of that triumph was written in bodies. The Central Pacific estimated that over 1,000 Chinese workers died during the construction of the line—one death for roughly every mile of track. The Union Pacific’s toll was lower, estimated at 400 to 500, but still significant. These were not random accidents; they resulted from pushing men to work faster than was safe in conditions that were inherently dangerous, with no safety equipment and no oversight.

The companies knew men would die. They accepted it as a cost of doing business. The workers had no choice. For the Chinese immigrants, the railroad was one of the few employers willing to hire them. Anti-Chinese sentiment was pervasive in California. They were excluded from most trades, barred from testifying in court, and subject to violence and discrimination. The railroad offered wages, however meager, and the possibility of survival.

For the Irish workers on the Union Pacific, the situation was similar. Fleeing famine and prejudice, they took the work because there was nothing else. The freed slaves who worked on the line were escaping the sharecropping system of the post-Civil War South. The railroad was brutal, but it paid cash. And for men with no other options, that was enough.

#### A Complicated Legacy

The legacy of the transcontinental railroad is complicated. It was an engineering marvel that transformed the economy, enabled the growth of cities, expanded agriculture, and facilitated the industrialization of the West. But it was also built on exploitation, on the labor of men who were treated as disposable, and on the destruction of Native American lands and ways of life.

The railroad brought settlers who displaced the tribes and buffalo hunters who slaughtered the herds to near extinction. The tribes knew what the railroad meant, and they fought it. They lost. The physical remnants of the construction are still visible today. In the Sierra Nevada, you can hike to the sites of the old tunnels—some still in use, widened and reinforced, carrying modern freight. Others are abandoned, sealed off, slowly being reclaimed by the mountains.

The roadbed, the graded shelf cut into the hillsides, is still there, overgrown with trees and brush but recognizable to anyone who knows what to look for. The retaining walls built by Chinese workers 150 years ago still stand, stones fitted so precisely that they haven’t shifted. In Nevada and Utah, the old grade is visible from the air—a scar running across the desert, parallel to the modern tracks.

Scattered along the line are the graves—small markers and forgotten cemeteries, piles of stones in the desert, places where workers were buried where they fell and never moved. Some of these graves have been located and documented by historians and archaeologists, but many remain lost.

The photographs from the era—though fragmentary and incomplete—show the scale of the work. Images of Chinese workers standing in a tunnel holding drills and hammers, their faces obsc