How One German Woman POW’s ‘STUPID’ Potato Trick Saved 3 Iowa Farms From Total Crop Failure

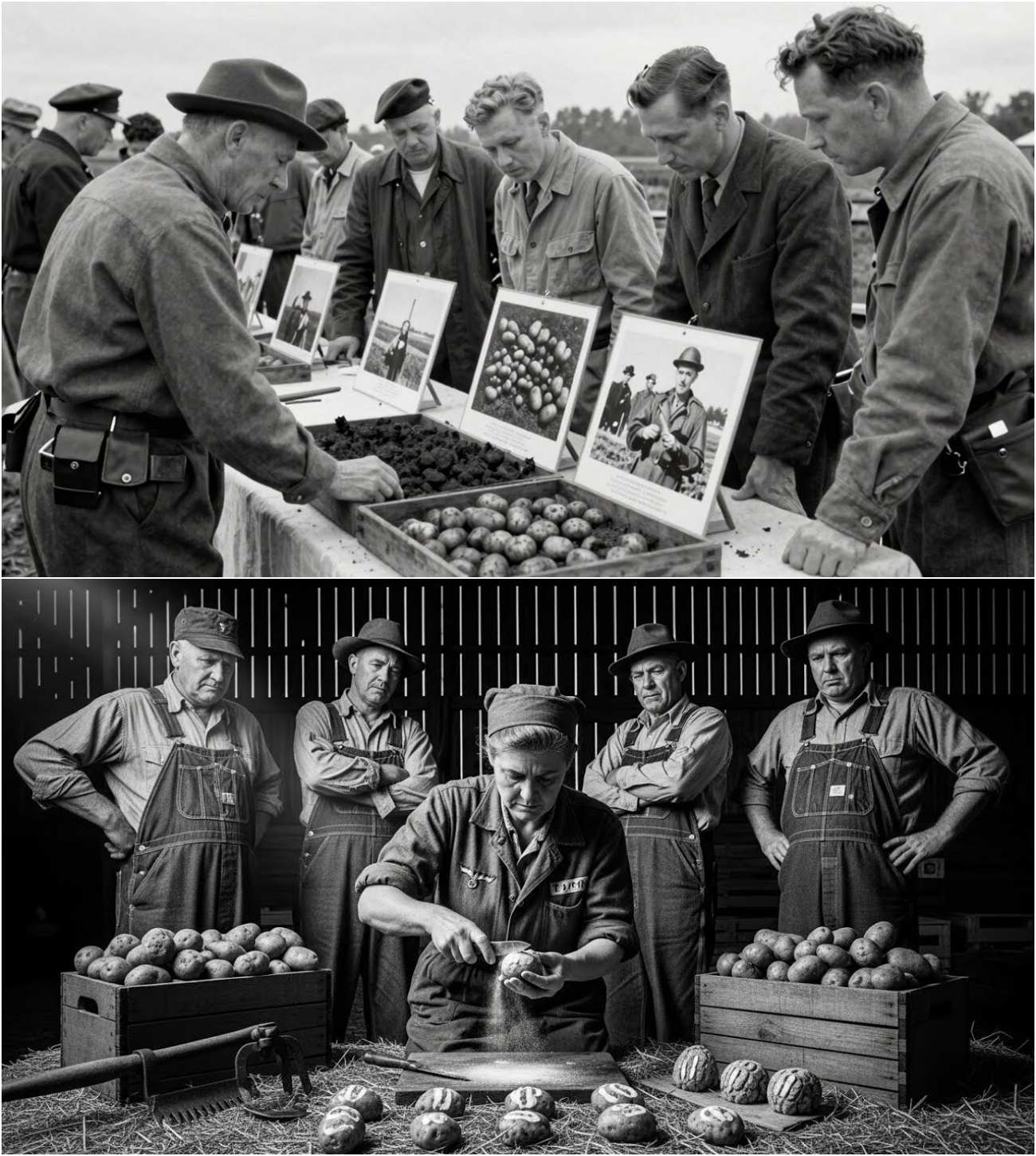

In late April 1946, as spring finally arrived in Iowa, the air was thick with tension and uncertainty. At the edge of a muddy field in Cedar County, Ernst Müller observed three American farmers engaged in a heated argument over a bucket of damaged seed potatoes. The men were frustrated, gesturing emphatically as they assessed the state of their crops, unaware that a quiet German woman standing nearby held the key to saving their farms.

The Arrival of Greta Schneider

Greta Schneider, a former agricultural laborer from Bavaria, was one of the last German prisoners of war still in the United States. Captured during the collapse of Germany, she had been assigned to work on local farms while American men served overseas. Unlike many of her fellow prisoners, Greta had no family left in Germany; her husband had died in the war, and her farm had been destroyed. She faced an uncertain future in a country that had been devastated by conflict.

The Cedar County Prisoner of War camp had been established in 1944 to house captured soldiers who worked on local farms. By spring 1946, most prisoners had been repatriated, but a small group remained to help with the agricultural season. Among them, Greta stood out—not only for her experience but also for her keen understanding of farming techniques that American farmers had yet to appreciate..

The Crisis at Hand

The three farmers—Thomas Henderson, Stan Kowalsski, and Harold Jensen—had come to rely heavily on the labor provided by the German prisoners. Henderson’s farm covered 240 acres, Kowalsski’s 180 acres, and Jensen’s 95 acres specialized in seed potatoes for regional distribution. However, in mid-April, they faced a dire situation when their seed potato shipments arrived damaged.

Spring had been unusually cold and wet, delaying planting by nearly three weeks. When the seed potatoes finally arrived, Henderson discovered that 40% of his order showed signs of rot, while Kowalsski faced an even worse situation with 60% of his potatoes compromised. Jensen, whose entire livelihood depended on producing certified seed stock, was left staring at boxes of potatoes that were either diseased or questionable.

The financial implications were staggering. Henderson stood to lose nearly $3,000, Kowalsski faced potential bankruptcy, and Jensen’s reputation as a certified seed producer hung in the balance. A meeting was hastily convened in Henderson’s barn to discuss their options. The mood was grim, and the farmers were at a loss, contemplating whether to reorder, risk planting compromised seed, or abandon the potato crop entirely.

Greta’s Intervention

While the farmers debated their options, Greta worked quietly in the barn, preparing equipment. Her English had improved significantly during her time in Iowa, and she understood enough of their conversation to grasp the severity of their predicament. After observing the farmers’ distress, she hesitantly approached them, asking if she could examine the seed potatoes.

Initially, the farmers found her request presumptuous, but desperation led them to grant her permission. Kneeling beside the boxes, Greta methodically inspected the potatoes, separating them into distinct piles. After nearly 20 minutes of examination, she looked up and explained that about 70% of what they considered ruined seed could potentially be saved using a technique her grandmother had taught her in Bavaria.

Skepticism and Tradition

The farmers exchanged skeptical glances. Thomas Henderson, the most experienced among them, felt irritation that their time was being wasted on what he considered folk remedies. Stan Kowalsski, who had rejected traditional European farming methods for modern techniques, was particularly dismissive. Harold Jensen, educated in modern agronomy, viewed peasant farming techniques as outdated.

Despite their skepticism, Greta persisted. She explained that the technique involved cutting away the diseased portions of the seed potatoes, treating the cuts with a specific mixture, and allowing them to cure under controlled conditions before planting. This process would take four to five days, but it could salvage seed that appeared beyond redemption.

When Henderson asked what this miraculous treatment consisted of, Greta’s answer struck the men as absurd. She required wood ash from hardwood trees, agricultural lime, and most importantly, what she referred to as “Schwefel pulver,” or sulfur powder. The mixture would be dusted onto the cut surfaces of the potatoes, which would then be stored in a dark, cool location with specific humidity conditions.

A Controlled Experiment

Harold Jensen immediately raised objections. While sulfur might have merit as a fungicide, he argued that combining it with wood ash and lime seemed like superstitious nonsense. The farmers pointed out that cutting seed potatoes was standard practice, but Greta insisted that her method was different.

After nearly 30 minutes of debate, Henderson proposed a compromise: they would conduct a controlled experiment. Greta would treat a portion of their damaged seed using her method while they planted a comparable amount of untreated seed as a control group. If her technique showed no improvement, they would only lose four days. The three farmers agreed, albeit with lingering skepticism.

Greta set to work immediately, requisitioning supplies from each farm. She converted a corner of Henderson’s potato cellar into her workspace, meticulously examining each potato. Using a sharp knife that she sterilized between cuts, she excised diseased portions with precision. The healthy remaining sections were dusted with her ash-lime-sulfur mixture, which she insisted needed to be maintained at specific temperatures and humidity levels.

Results of the Experiment

Four days later, Greta informed the farmers that the treated seed was ready for planting. What they saw astonished them. The cut surfaces had developed a tough, corky layer that sealed the exposed flesh, and many of the treated pieces had begun developing sprouts from viable eyes. This was a remarkable transformation from what had appeared to be worthless seed.

The treated seed potatoes were planted in designated sections of each farm, clearly marked and separated from the control plantings of untreated damaged seed. As nature took its course, the farmers tended to their fields, resigned to poor germination rates from the untreated seed.

By mid-May, the first indications of something extraordinary emerged. Thomas Henderson noticed that the treated section of his potato field showed significantly higher emergence rates than the control section. Where the control section displayed sparse growth, the treated section boasted robust emergence approaching 90%. Stan Kowalsski observed similar patterns, and Harold Jensen’s results were even more dramatic.

By early June, the difference became undeniable. The treated potatoes developed into healthy plants, while the control plants remained sparse and stunted. Thomas Henderson calculated that the treated section would yield approximately 70 to 80% of what he would normally expect from premium seed, while the control section would yield less than 30%.

A Lasting Impact

As the harvest approached, the three farmers stood in Jensen’s field, marveling at the stark contrast between the thriving treated plants and the struggling control section. The treated potatoes produced plants that met certification standards for seed stock production, while the control section was a complete loss.

Financially, the impact was transformative. Henderson estimated that Greta’s technique had saved him approximately $2,300. Kowalsski estimated his savings at roughly $2,700, while Jensen calculated that the technique had preserved his certification status, saving him from losses exceeding $4,000.

The three farmers attempted to compensate Greta beyond her standard wages, but camp regulations prohibited prisoners from receiving additional payment. Instead, they petitioned the camp commander and eventually the State Department to allow Greta to remain in the United States after her official repatriation date.

A New Beginning

In December 1946, as other German prisoners boarded ships for their journey back to Europe, Greta Schneider received provisional immigration status to remain in Iowa as an agricultural consultant. She was released from prisoner status and employed by the Iowa State Extension Service to teach seed potato salvage techniques to farmers across the state.

Over the next three years, Greta conducted more than 140 workshops throughout Iowa and neighboring states. She taught farmers not only the seed potato treatment technique but also other European methods for crop preservation and resource-efficient agriculture. Her contributions were particularly valuable during the late 1940s when post-war inflation made farming inputs expensive.

Greta Schneider’s story became emblematic of a subtle shift in American agriculture during the post-war period. The techniques she introduced were not merely about salvaging potatoes; they represented a fundamentally different philosophical approach to farming. American agriculture, blessed with abundant land and capital, had evolved toward mechanization and specialization, while European agriculture had developed through centuries of resource scarcity.

A Legacy of Knowledge

The three Iowa farms that faced potential ruin in April 1946 thrived for decades afterward. The Henderson property remained in family operation until 1992, the Kowalsski farm continues operating today under third-generation management, and the Jensen seed potato operation expanded significantly before selling in 2003.

In 1989, a small plaque was erected at the Cedar County Agricultural Extension Office commemorating Greta Schneider’s contributions to Iowa agriculture. The inscription read simply: “Greta Schneider, 1908 to 1987. Agricultural educator who taught Iowa farmers that wisdom transcends borders and that solutions often come from unexpected sources.”

Greta’s knowledge saved countless farms and enriched American agriculture immeasurably. Her story is ultimately one of humility, openness to learning, and the recognition that expertise exists in many forms. The experience taught the farmers that education and intelligence are not synonymous, and that traditional knowledge passed through generations often contains profound wisdom that formal education overlooks.

In the end, Greta Schneider’s “stupid” potato trick did more than save three Iowa farms; it transformed agricultural practices and fostered a spirit of collaboration and respect that transcended national boundaries. It serves as a powerful reminder that sometimes the most effective solutions come from the most unexpected places and that the willingness to listen and learn can lead to remarkable outcomes.