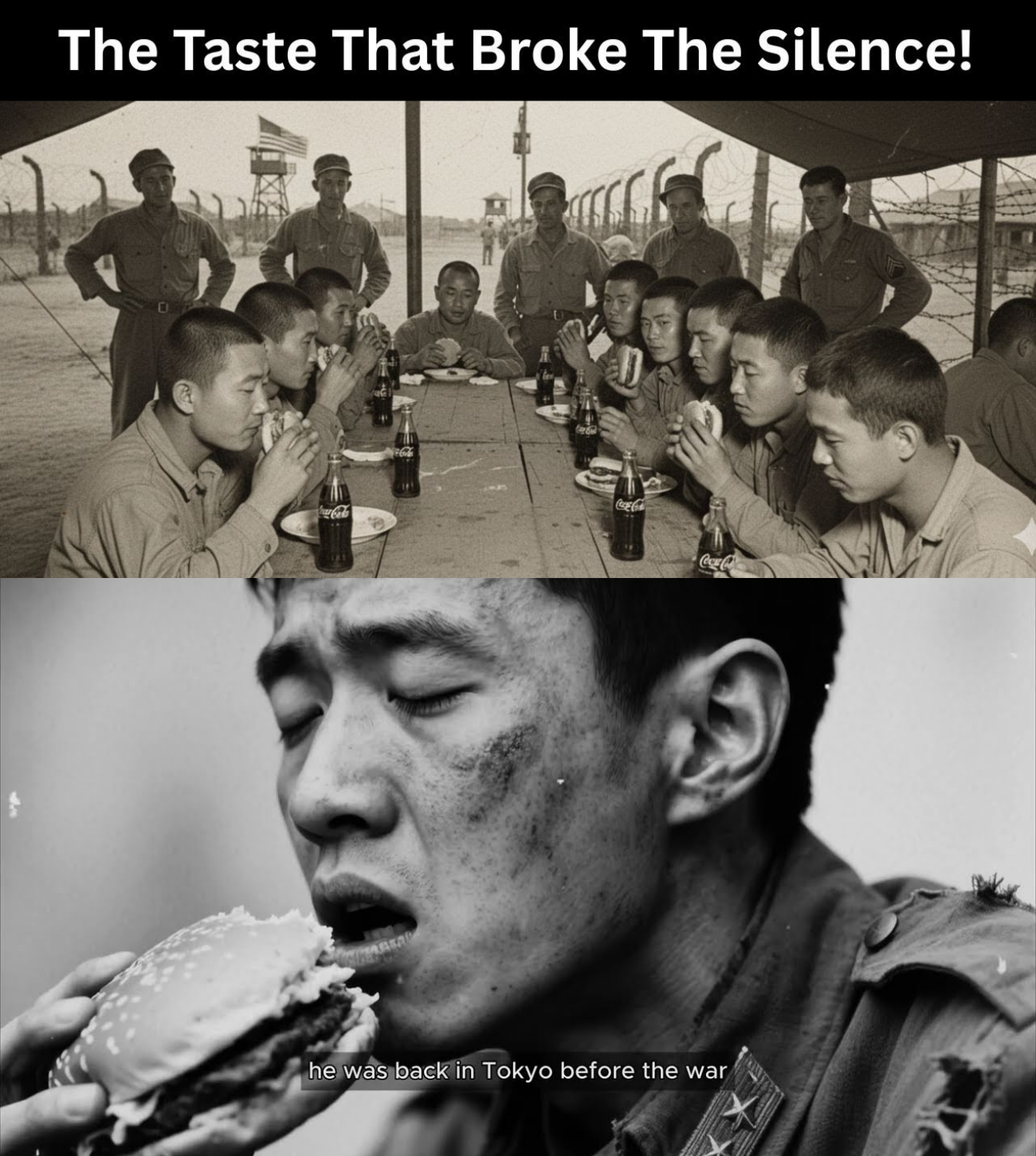

Japanese POWs Broke Down After Tasting Hamburgers and Coca-Cola in U.S. Camps

On December 3, 1944, a cold, biting wind swept across Camp McCoy in Wisconsin, as a train carrying Japanese prisoners of war (POWs) came to a halt. The heavy doors creaked open, revealing men who had endured unimaginable hardships—men whose lives had been defined by war, starvation, and the relentless grip of fear. As they stepped onto the frozen ground, their tattered uniforms and hollow faces told a story of suffering that words could scarcely capture.

A Harsh Reality

These prisoners had been conditioned to expect the worst. For years, they had been told that capture meant torture, humiliation, and death. They envisioned a brutal fate at the hands of their captors, yet as they stood in formation, trembling not only from the cold but from confusion, they were met with an unexpected reality. Instead of violence, they were greeted by the rich, tantalizing aroma of food wafting through the air—a scent they had long forgotten.

As the smoke curled from kitchen chimneys, the men exchanged wary glances, unsure of what to make of this new experience. One soldier whispered to another, “This must be the trap.” Little did they know, this was merely the beginning of a profound transformation that would challenge everything they had been taught about their enemy.

The War They Knew

The Pacific War had been brutal and unforgiving. By late 1944, Japan’s supply lines were collapsing, leading to widespread starvation among soldiers stationed on distant islands. Many fought with swollen bellies, malnourished bodies, and the constant specter of death looming over them. In stark contrast, the United States was thriving, producing food, fuel, and military equipment at an unprecedented scale. The disparity between the two nations was staggering, and the POWs were about to confront the harsh reality of this imbalance.

Among them was Sergeant Hideo Tanaka, a 23-year-old soldier who had been captured on Saipan after two weeks of hiding in a cave, surviving only on roots and rainwater. When American soldiers found him, he braced himself for execution, but instead, they bandaged his wounds and transported him to a ship. Now, standing in the snow at Camp McCoy, Tanaka was overwhelmed by the kindness he had not expected.

The First Night

As the intake process began, the men were subjected to delousing and medical examinations that felt almost surreal. American medics tended to their wounds with a care that was foreign to them. Tanaka watched as a medic cleaned the infected arm of an older prisoner, applying sulfa powder and fresh gauze. The sight of this compassion tightened Tanaka’s throat, forcing him to confront the propaganda he had consumed about Americans being savages.

That first night, lying on a cot under a wool blanket, Tanaka stared at the ceiling beams, grappling with the conflicting emotions swirling within him. Some prisoners whispered about the deception they believed they were experiencing, while others began to contemplate the possibility that their enemy lived in a different world altogether—a world of abundance, kindness, and normalcy.

Breakfast: A Moment of Transformation

When morning arrived, it brought with it an experience that none of the prisoners were prepared for—breakfast. The mess hall was warm and filled with steam rising from serving trays. The aroma hit the prisoners like a wave, rich and fatty, reminiscent of a life they had long since been deprived of. As they shuffled through the line, their tin trays clutched tightly, they were filled with a mix of hunger and trepidation.

As Tanaka approached the serving counter, an American cook dropped a hot hamburger patty onto a soft bun, followed by a serving of fried potatoes. Then came the moment that would forever change their perception—he slid a glass bottle onto the tray, its label reading “Coca-Cola.” Tanaka had never seen such a thing before.

Whispers rippled through the line. “Meat? They’re giving us meat?” At the tables, the prisoners sat in stunned silence, staring at the food with suspicion, hunger, and a dawning realization that perhaps this was not a trick after all. One man lifted the bottle to his lips, and after taking a sip, his eyes widened in disbelief. The sweetness exploded on his tongue, followed by the sharp burn of carbonation, leading him to laugh in astonishment.

Tanaka took his first bite of the hamburger, and the flavor overwhelmed him. The salt, grease, and char from the grill transported him back to Tokyo, where he had once enjoyed yakitori from street vendors. But this was different—this was a weighty, filling meal, unlike anything he had experienced in two years. As he drank the Coca-Cola, he thought of his family back home, the rations they endured, and the deep shame that washed over him for eating better as a prisoner than he ever had as a soldier.

The Emotional Aftermath

Around him, other men wept quietly, some hiding their faces, others staring blankly at the walls. The American guards, oblivious to the emotional upheaval unfolding among the prisoners, saw this as routine—a standard procedure in the treatment of POWs. But for the men who had endured so much, this meal was an earthquake, shaking the very foundations of their beliefs about their captors.

As the days turned into weeks, life at Camp McCoy settled into a routine. The prisoners cleared snow from roads, received medical care, and attended English classes. Tanaka found solace in learning the language, repeating words slowly and carefully, each syllable a step toward reclaiming his humanity. Yet, the memories of his family and the uncertainty of their fate haunted him.

One afternoon, while working outside the camp, Tanaka encountered an American farmer who harbored resentment for the Japanese soldiers. The farmer’s cold eyes and harsh words reminded Tanaka that not all Americans were kind. The tension simmered beneath the surface, as some prisoners warned against softening their resolve, fearing that kindness was a trap.

A New Perspective

Despite the challenges, Tanaka began to see glimpses of humanity in the unlikeliest of places. An American guard named Miller sometimes lingered near the fence after his shift, sharing photographs of his family with the prisoners. Tanaka traced the outline of a small house in the dirt, and when Miller smiled and nodded, he felt a connection that transcended the barriers of war.

As the war raged on, rumors of Japan’s impending defeat began to circulate. Tanaka’s world shifted as he grappled with the reality of a nation on the brink of collapse. The stark contrast between his experiences in America and the grim situation back home weighed heavily on him. He had been fed, cared for, and treated with respect, while his family endured unimaginable suffering.

The End of an Era

When the news of Hiroshima and Nagasaki broke, the camp fell into a heavy silence. The prisoners processed the loss of their homeland, their families, and the ideals they had fought for. Tanaka felt only numbness, grappling with the reality that he might never know his mother’s fate.

As preparations for repatriation began, the prisoners received clean uniforms and medical checks. On the day of departure, they filed out of the barracks, carrying small bundles of belongings. Tanaka glanced back at the camp, feeling a mix of confusion, gratitude, and shame. He had expected cruelty, yet he had received hamburgers and kindness.

Returning Home

The journey back to Japan was long and arduous. As Tanaka stepped onto Japanese soil, he was met with a world transformed by war. Cities lay in ruins, families were scattered, and hunger was rampant. The neighbor who delivered the news of his mother’s death shattered the last remnants of his hope.

In the weeks that followed, Tanaka worked tirelessly to rebuild, clearing debris and helping others find their way in a shattered world. One evening, a thin child approached him, asking for food. Tanaka reached into his pocket and pulled out the last piece of chocolate he had saved from the camp, unwrapping it slowly and placing it in the boy’s palm. The child’s eyes lit up with joy as he savored the sweetness, and in that moment, Tanaka felt a flicker of warmth return to his heart.

A Legacy of Humanity

Years later, when Tanaka’s son asked about the war, he chose his words carefully. He spoke not of battles or glory but of the small acts of humanity that had left an indelible mark on his soul. “I learned in America,” he said quietly, “that kindness is harder to carry than cruelty. Cruelty you can fight. Kindness you remember.”

Tanaka’s story serves as a powerful reminder of the enduring impact of compassion, even amidst the horrors of war. The legacy of Camp McCoy and similar camps is not found in military strategy or victory, but in the quiet moments when humanity broke through the darkness. The hamburgers, the Coca-Cola, the shared smiles—all of these moments remind us that even in the most trying times, we can find common ground and connection.

As we reflect on Tanaka’s experience, we are reminded of the power of kindness and the importance of recognizing our shared humanity. In a world often divided by conflict, these stories inspire us to seek understanding and compassion, reminding us that, ultimately, we are all human.