Japanese POWs in Wisconsin Were Served White Rice — They Thought It Was a Death Row Meal

February 23, 1944—Camp McCoy, Wisconsin.

The train rolled slowly into the snowy fields of the American Midwest, carrying 183 Japanese prisoners of war. The temperature outside had dropped to 14°F below zero. Inside the passenger cars, the men shivered, frost covering the windows as the cold seeped into their bones. They had traveled for days—displaced, hungry, terrified, uncertain of what awaited them.

As the train came to a halt, Lieutenant Commander Teeshi Yamamoto—one of the senior officers among the captives—pressed his face against the frozen glass, staring at the vast expanse of snow that stretched as far as the eye could see. He had expected many things upon his surrender in the Aleutian Islands six months prior: interrogation, hard labor, perhaps even execution. But snow? He had never imagined snow like this. He whispered a phrase to his fellow officers, one that would prove tragically ironic in the days to come.

“Whatever happens here, we must die with honor.”

The Warped Expectations of a Japanese Officer

Yamamoto and his men had been trained for one reality: the brutal treatment of prisoners by the enemy. Nazi propaganda, combined with military indoctrination, had painted Americans as barbaric, ruthless enemies—enemies who would strip them of their dignity and their lives.

On their journey across the Pacific, rumors had circulated about the horrors awaiting them in American hands. They were told that Americans would treat them as less than human, subjecting them to torture and humiliation. They had come to believe that surrender meant dishonor—and death. Yet as the train approached Camp McCoy, something unexpected was unfolding.

Instead of the cruelty they had been taught to expect, Yamamoto and his men were met with something that shook them to their core: compassion.

The First Surprises: Kindness Beyond Imagination

As the men filed off the train into the bitter cold, they noticed something different about the American guards waiting on the platform. These men were armed, yes, but their faces were not twisted with hatred. Instead, they looked almost concerned, as if they were worried for the prisoners’ well-being. The guards ushered the men toward warm buildings, their voices lacking the contempt they had been conditioned to expect.

Captain Robert Henderson, the camp’s liaison officer, stood among them, speaking through a translator. Sergeant Henry Tanaka, a Japanese American, was there to help bridge the language gap.

“This way, gentlemen,” Captain Henderson called, his voice calm and measured. “We have warm buildings waiting.”

The prisoners exchanged bewildered glances, unsure how to process this unexpected treatment. In Japan, surrender was seen as a grave dishonor, and the idea that the enemy would show kindness was almost unthinkable. But here, in the middle of a foreign land, it was becoming impossible to deny that they were being treated better than they had ever imagined possible.

As they entered the barracks, they were led to coal-burning stoves that provided blessed warmth. They crowded around the heat, their frozen fingers trembling as they warmed themselves. American soldiers brought out wool coats, thick socks, and insulated boots for the prisoners. This was a gesture that had no precedent in their understanding of warfare.

One of the men, Enen Hiroshi Nakamura, a young pilot who had been shot down over Atu Island, whispered in confusion, “Why are they giving us these things?”

Yamamoto’s mind raced. “Accept nothing as kindness,” he cautioned. “This may be a trick to lower our guard.”

But the truth was, nothing about this situation made sense. The prisoners, accustomed to being treated as expendable, were now being offered warmth, shelter, and even food. It felt wrong to accept these comforts, but their bodies couldn’t help but crave the relief they were being offered.

The White Rice That Led to Misunderstanding

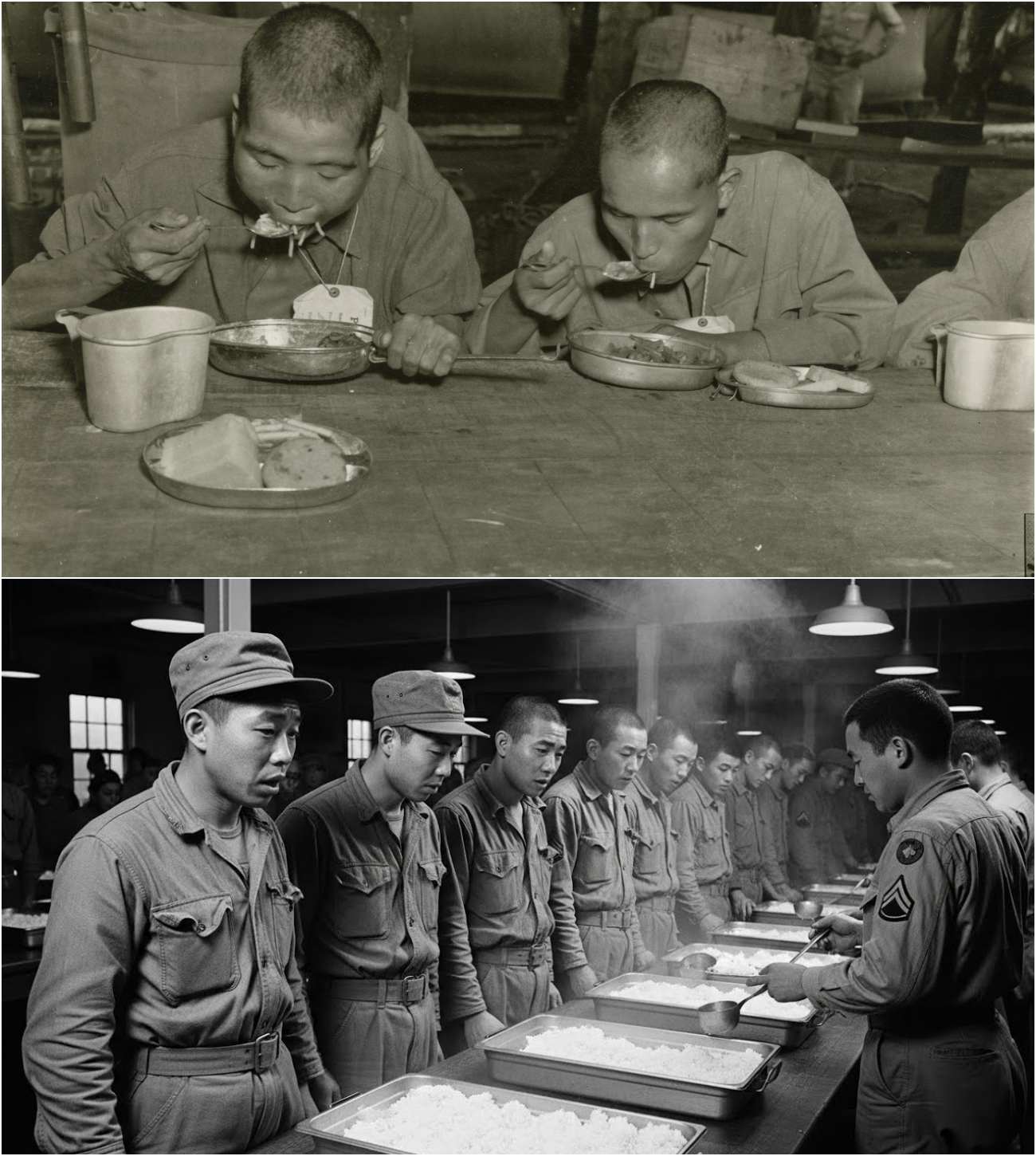

That evening, after settling in, the prisoners were told that dinner would be served in the mess hall. Most expected another round of disappointment, possibly some meager rations, but they didn’t know what was coming.

When they entered the mess hall, the air was filled with the unmistakable smell of rice. But this wasn’t just any rice.

This was white rice.

It was perfectly white, each grain distinct and gleaming. For the Japanese prisoners, white rice was a luxury few could ever dream of. In Japan, this type of rice was reserved for officers and wealthy civilians—a treat that rarely made it to the tables of soldiers, let alone prisoners of war.

Yamamoto’s face drained of color as he observed the rice. His worst fears were confirmed. In Japanese culture and military tradition, condemned prisoners were given a final meal of white rice, red beans, and fish—the finest foods—as a final gesture of respect before their execution.

The realization hit Nakamura first. His voice trembled as he whispered, “They are going to execute us.”

The murmurs spread quickly through the prisoners. They didn’t speak of hunger or shame, but of death. They believed this was their last meal. The white rice—this unexpected, extravagant dish—was the signal that their end had come.

Some of the men began to weep quietly. Others stood rigid, attempting to maintain the dignity expected of Japanese servicemen even in their final moments. They were ready to die with honor. They had been told that surrender meant death—but they never imagined their final meal would be served with such unsettling kindness.

Yamamoto, as the senior officer, stood up to maintain order. He addressed the men in Japanese, his voice steady despite the fear that had taken hold of him. “We knew this day might come when we were captured,” he said. “We will face what comes with courage. Eat the meal they have given us. Do not give them the satisfaction of seeing us break.”

The prisoners ate in near silence. Many with tears streaming down their faces. Some refused to eat at all, sitting still with their heads bowed as if in prayer. They were distraught, unable to reconcile what was happening with the teachings they had grown up with.

The Moment of Revelation: Misunderstanding and Compassion

After dinner, Captain Henderson approached Sergeant Tanaka with confusion. “What’s happening?” he asked. “Why are they so upset?”

Tanaka returned with a stunned expression after speaking to several prisoners.

“Sir,” Tanaka said, his voice low, “they think you’re going to execute them.”

Henderson’s jaw dropped. “What? Why would they think that?”

“The rice, sir,” Tanaka replied. “In Japanese tradition, condemned prisoners receive white rice as part of their last meal. They’ve never seen prisoners of war treated this way. They think the rice means they’re going to be shot.”

The realization hit Henderson like a slap. This misunderstanding, this cultural clash, could have led to irreparable damage. The very thing meant to calm the prisoners—the white rice—had created a terrifying panic.

Within the hour, a meeting was convened with the officers and interpreters. Henderson stood before the prisoners once again, trying to undo the damage.

“Gentlemen,” he began, “I want you to understand that there has been a terrible misunderstanding. You are not going to be executed. The white rice is not a final meal. This is simply what we serve at this camp. You will receive white rice at every meal along with meat, vegetables, and bread. This is standard treatment for all prisoners of war under the Geneva Convention.”

For a moment, the prisoners simply stared, unable to comprehend. Then, one of them—Nakamura—began to laugh. It started as a quiet chuckle but soon became hysterical. The laughter spread, first slowly, then faster, as the men realized the truth. They had misunderstood everything. They were not being led to their deaths. They were being treated like human beings.

A Transformative Experience

In the weeks that followed, the reality of Camp McCoy began to sink in. The prisoners worked alongside American soldiers, cutting timber, planting crops, and maintaining the camp’s facilities. The labor was not brutal. It was fair, and it was paid—in camp script, which they could use to purchase goods from the camp store. The store was stocked with items like cigarettes, candy, and even musical instruments.

For the first time, these prisoners, who had been taught to see their captors as monsters, began to question everything they had been told.

Lieutenant Commander Yamamoto began to keep a detailed diary of his experiences. In one entry from February 23, 1944, he wrote:

“Today we received our third consecutive meal of white rice, also beef stew with carrots and potatoes. The portions are generous. No one is hungry. I do not understand this. At Rabul, our own troops were eating rice mixed with anything we could find, roots, leaves, insects when we could catch them. Here in an enemy prison camp, we eat better than we did when serving our emperor.”

It wasn’t just the food. It was everything. The kindness. The humanity. The basic decency they had never expected.

The American guards, who had initially viewed their prisoners with suspicion, began to see them differently. They no longer saw faceless enemies—they saw individuals. Young men who were more than the uniforms they wore.

Yamamoto, once taught to hate and fear Americans, began to see them not as demons, but as men of honor. He learned that his captors followed laws, that they showed mercy where he had expected cruelty. And for the first time in his life, he began to question the propaganda that had shaped his worldview.

As the months passed, the relationship between the prisoners and the American guards evolved. They shared stories of their lives, their families, their hopes for the future. Yamamoto became a bridge between the two sides, helping his fellow prisoners to navigate the overwhelming kindness of their captors.

The Lesson Learned

In the fall of 1945, as the war came to an official end, Yamamoto was scheduled to return to Japan. Before his departure, Captain Henderson hosted a small farewell dinner, where Yamamoto delivered a speech that would stick with everyone who heard it.

“You showed me that my enemies could be men of honor,” he said. “You challenged everything I believed about Americans, about this conflict, about the meaning of duty and humanity.”

And in that moment, a powerful truth took root.

The war had broken them, but in the end, it was the small gestures of kindness—a bowl of rice, a letter from home, a conversation—that began to heal their wounds.

What had been a battlefield of ideologies became a common ground for reconciliation.

The story of Camp McCoy reminds us that the most profound changes happen in the smallest moments—when we recognize the humanity in those we once feared. It is a story of transformation—not through battle, but through understanding.

And it began with a simple meal of white rice.