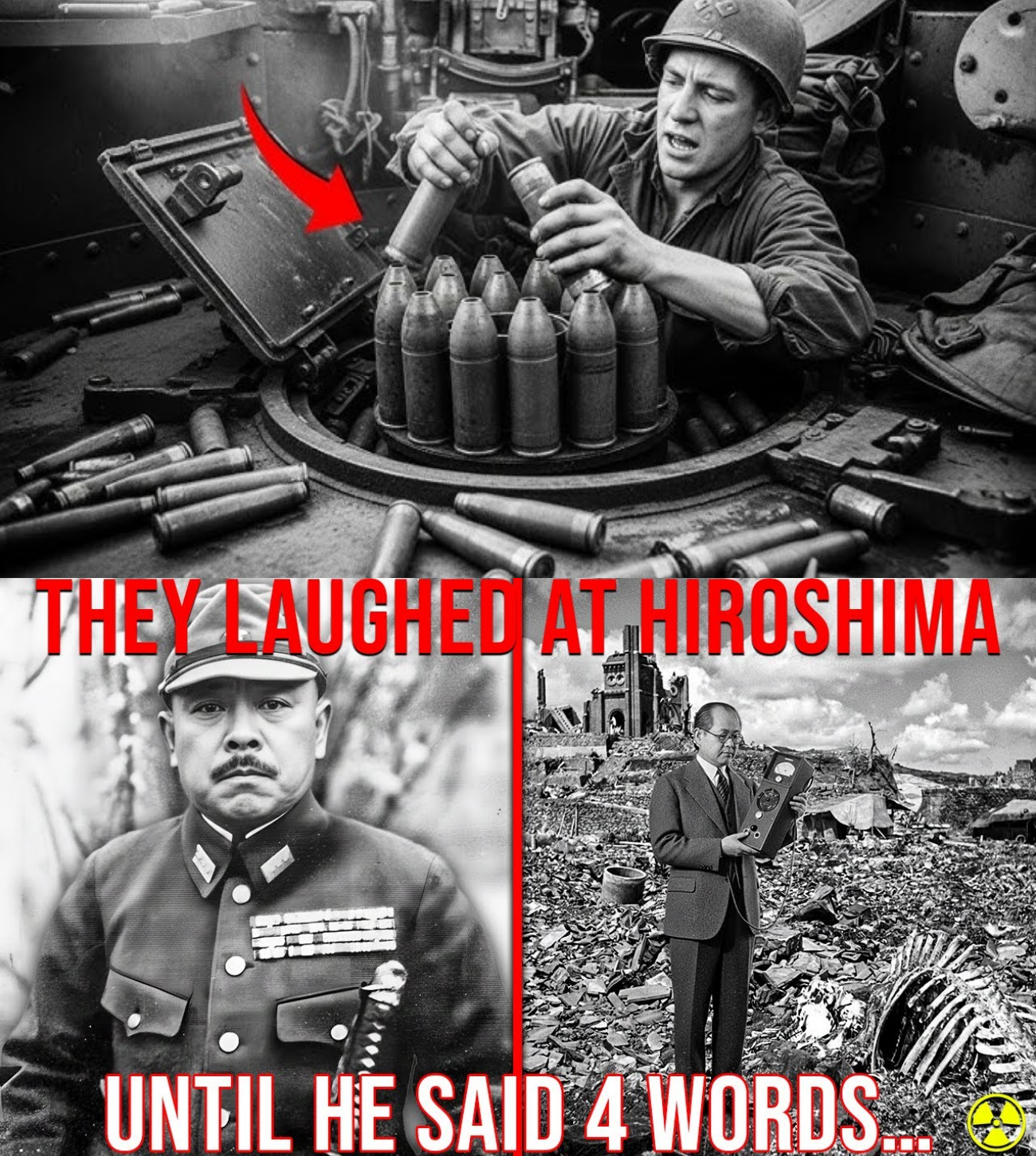

Japan’s Generals Laughed When They Heard About Hiroshima… Until This Man Walked In

On August 6, 1945, a single B-29 bomber released its deadly payload over Hiroshima, marking a pivotal moment in world history. As the bomb exploded, creating a fireball that would consume everything in its radius, the Japanese leadership remained largely oblivious to the magnitude of the event. In Tokyo, War Minister Korachica Anami dismissed the reports of destruction as mere American propaganda, believing firmly in the resilience of the Japanese spirit. However, everything was about to change, and it would take just four words to shatter their denial: “This was atomic fission.”

The Initial Denial

In the immediate aftermath of the bombing, communication lines to Hiroshima went silent. The city, once bustling with life, was now reduced to ruins. Yet, for the Japanese military leaders, this was not an unprecedented scenario. American B-29 bombers had been systematically devastating Japanese cities for months, with firebombing raids resulting in catastrophic casualties—one such raid on Tokyo had killed over 100,000 people in a single night.

As vague reports trickled into Tokyo about a new type of bomb causing unprecedented damage, the Imperial War Cabinet dismissed them. They believed the Americans were merely attempting to shock Japan into submission with exaggerated claims. Anami’s response reflected the prevailing attitude: “The Japanese spirit will prevail.” For 48 hours, the leadership held onto their denial, convinced that the war would continue despite the growing evidence to the contrary.

The Investigation Begins

By August 7, the Imperial War Cabinet realized they needed to understand the situation in Hiroshima better. They dispatched an investigation team led by Lieutenant General Cizo Arisu. However, the team faced immediate obstacles; Hiroshima’s airport was nonexistent, and the railway tracks leading into the city were obliterated. Thus, they embarked on a 30-mile trek through the radioactive ruins.

What they discovered was staggering. As Richard Frank describes in his work, the last stretch of their approach revealed a landscape of utter devastation. First came shattered windows, then collapsed buildings, and finally, an expanse of flattened earth where 90,000 structures once stood. The report they submitted to Tokyo was clinical and devastating, detailing how a single bomb had created a fireball one mile in diameter, with blast effects extending over four miles. The thermal radiation had ignited flammable materials up to two miles from the epicenter of the explosion.

The Arrival of Yoshio Nisha

Yet, Tokyo still needed confirmation. Was this truly atomic fission, or just a massive conventional explosion? To answer this question, they turned to Yoshio Nisha, Japan’s leading nuclear physicist, who had been attempting to develop Japan’s own atomic bomb since 1941. On August 8, Nisha entered the ruins of Hiroshima armed with a Geiger counter, ready to assess the situation.

The findings he reported were unequivocal. Nisha detected residual gamma radiation, specific isotope signatures, and blast patterns consistent with an airburst detonation at optimal altitude. The physics were irrefutable: this was not merely a scaled-up chemical explosion; it was a transformation of matter into energy. His official report to the war cabinet contained a critical assessment: “The Americans have succeeded in uranium fission. Based on industrial capacity, they likely have produced at least three bombs with more to follow.”

This revelation was catastrophic for the Japanese leadership. While one bomb could be dismissed as a fluke, the existence of multiple bombs indicated industrial-scale production capabilities. It meant that every major Japanese city could be obliterated one by one, without a single American soldier setting foot on Japanese soil.

The War Cabinet’s Dilemma

On August 9, the Imperial War Cabinet convened to discuss Nisha’s findings. The meeting lasted four hours, but no consensus emerged. Hardliners, led by Anami, argued for continuing the fight. They believed the Japanese spirit remained unbroken and that the Americans would eventually have to invade, which would lead to a costly confrontation. They clung to the hope that Operation Ketsugo, a plan for a massive defense, would allow Japan to inflict heavy casualties on the invaders.

However, as the meeting unfolded, news arrived from Nagasaki. At 11:02 a.m. on August 9, while the war cabinet debated, a second atomic bomb was dropped, destroying the city. The timing was catastrophic for Japanese leadership; they had convinced themselves that even if the first bomb was real, producing another would take months. Nagasaki proved them wrong.

But the situation grew even more dire. That same day, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and invaded Manchuria with 1.5 million troops. The Japanese strategy had relied on the assumption that Soviet neutrality would provide them with a buffer against American aggression. With the Soviets now joining the fray, Japan faced enemies on every front and had no diplomatic options remaining.

The Emperor’s Call to Action

As the reality of their situation sank in, Emperor Hirohito convened an Imperial conference in the Palace Air Raid shelter on the night of August 9. The military faction, led by Anami, argued for Ketsugo—continuing the fight to the bitter end. They believed that 100 million Japanese should die as one rather than accept defeat. The civilian faction, led by Foreign Minister Shigenori Togo, argued that further resistance was suicide. The Americans could destroy Japan city by city without ever landing troops.

The cabinet was deadlocked, with three members on each side. In 2,000 years of Japanese history, the emperor had never broken a cabinet tie on matters of war. Emperors typically ratified the consensus of their advisers, but at 2 a.m. on August 10, Prime Minister Kantarō Suzuki did something unprecedented: he asked Emperor Hirohito to decide.

Hirohito’s response, preserved in the Yale Avalon Project archives, was profound. He stated, “I have given serious thought to the situation prevailing at home and abroad and have concluded that continuing the war can only mean destruction for the nation. I cannot bear to see my innocent people suffer any longer.” He echoed a sentiment that would resonate throughout history: “We must endure the unendurable and suffer what is insufferable.” The emperor had spoken—Japan would surrender.

The Last Samurai’s Final Act

War Minister Anami left the conference in silence, but in the days that followed, he continued to perform his duties, implementing the emperor’s decision while hardline officers plotted a coup to prevent the surrender broadcast. Anami quietly refused to join them, believing that the emperor’s decision was final.

On the morning of August 15, just hours before Emperor Hirohito’s surrender broadcast would reach the Japanese people, Anami committed seppuku in his office. His suicide note, preserved in the National Archives of Japan, contained no justification for continuing the war. It simply read: “Believing firmly in the eternity of our divine land.” Anami, the last samurai of Imperial Japan, died believing he had failed.

In reality, he had spent his final days ensuring that the emperor’s decision would be carried out. He prevented the hardliners’ coup and made certain that Japan’s surrender would be complete and unconditional.

The Surrender Broadcast

At noon on August 15, 1945, the Jewel Voice broadcast aired across Japan. For many citizens, it was the first time they had ever heard their emperor’s voice. The broadcast was brief, lasting less than five minutes. It mentioned the atomic bombs only once, stating, “The enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to do damage is incalculable.”

In just 96 hours, Japan had gone from denial to acceptance. The most militarized nation on Earth, prepared to sacrifice every civilian in defense of the homeland, was brought to its knees not by an overwhelming invasion but by the brutal realization that resistance was physically impossible.

Conclusion: A Lesson in Human Resilience

War Minister Anami had laughed at American propaganda on August 6, but by August 15, he had taken his own life, not out of cowardice but as a testament to the profound shift in understanding that had occurred. A physicist had walked through the radioactive ruins of Hiroshima and confirmed that the war Japan was prepared to fight no longer existed.

The story of Japan’s surrender is a powerful reminder of how quickly the tides of war can turn. It illustrates the fragility of human resolve in the face of overwhelming technological and strategic advancements. The atomic bomb was not just a weapon; it was a harbinger of a new era in warfare, one that would forever alter the course of history.

As we reflect on these events, we are reminded of the delicate balance between power and humanity, and the profound consequences that arise when that balance is disrupted. The legacy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki serves as a somber reminder of the cost of war and the importance of pursuing peace in a world where the stakes have never been higher.