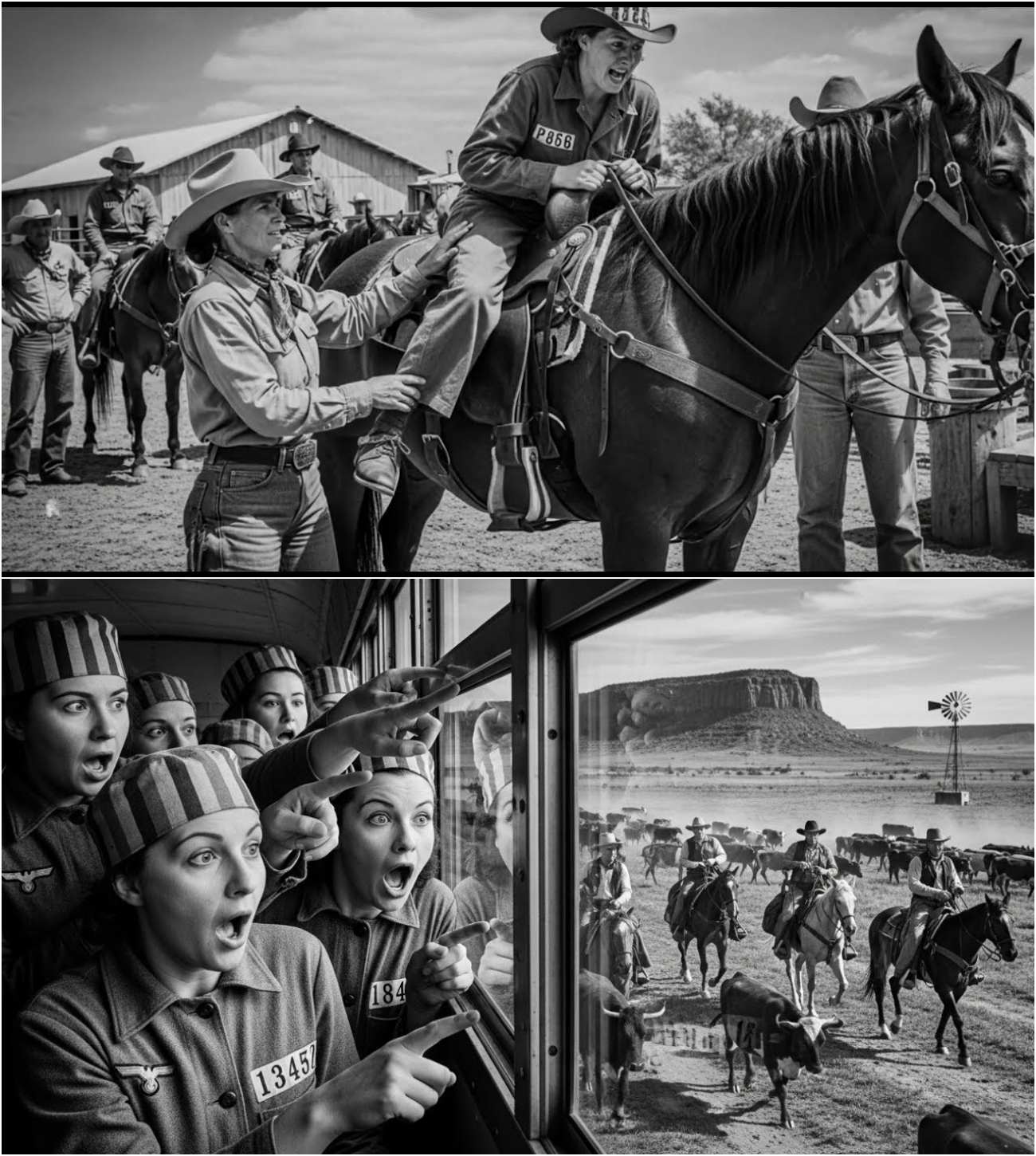

“Real Cowboys!” German Female POWs Shocked to See Cowboys Riding Horses in Texas

In July 1944, a dusty bus rolled through the vast Texas landscape, carrying a group of German female prisoners of war. Among them was Oberlieutenant Greta Schneider, who pressed her face against the window, captivated by the unfamiliar sights outside. After two months in a processing facility in New York, they were finally arriving at Camp Hereford, Texas, but nothing could have prepared them for the reality they were about to encounter.

As the bus turned onto a dirt road, Greta and her fellow prisoners witnessed something that seemed straight out of a Hollywood film: cowboys on horseback herding cattle across the open range. Dressed in wide-brimmed hats, leather chaps, and boots with glinting spurs, these men were living embodiments of the cowboy mythos Greta had previously dismissed as mere fantasy. “Are those actually cowboys?” whispered Leisel Hoffman, a former Luftwaffe communications officer sitting beside her. The sight was surreal—these were real American cowboys, not the romanticized versions they had seen in movies.

Greta had always believed that the American West was a thing of the past, a nostalgic mythology rather than a current reality. Yet here they were, men on horseback, demonstrating skills that seemed ancient and authentic. The bus continued towards the camp, and the landscape unfolded like a scene from a Western film: vast open ranges, cattle grazing freely, and men on horseback managing livestock with an ease that spoke of lifetimes spent in the saddle.

As the bus came to a stop, Sergeant Williams greeted them in careful German. “Welcome to Texas, ladies. You’ll be working on ranches around here as part of the prisoner labor program.” Greta’s mind raced with confusion and disbelief. She was a supply officer in the Wehrmacht, trained in logistics and administration, not agriculture or animal husbandry. “Working on ranches?” she asked, incredulous.

Williams explained that Texas ranches needed labor due to the men being off fighting in Europe and the Pacific. German prisoners were filling in the gaps. Greta struggled to comprehend this unexpected turn of events. The camp existed specifically to provide agricultural labor for Texas ranching operations, and the women would be trained in cowboy skills and deployed to local ranches.

That night, lying in her bunk, Greta tried to process her new reality. Captured in France, transported to America, and now about to become a cowgirl. Outside, she could hear the sounds of cattle lowing and horses nickering, a backdrop to her impossible new life. The next morning, she and eleven other women climbed into a ranch truck driven by Jim Henderson, a man who looked like he had stepped directly from a Western film.

“Y’all are assigned to the Double H Ranch, my family’s operation,” he announced, his Texas drawl thick and warm. “We run about 2,000 head of cattle on 50,000 acres. Right now, we’re short-handed, so you’re going to learn cowboy work whether you think you can or not.”

Greta’s heart raced with a mix of fear and excitement. “Ever been on a horse?” Henderson asked, glancing at the women in the rearview mirror. They all shook their heads. “Well, you’re going to learn today. Can’t work cattle in Texas without being able to ride.”

The drive to the ranch took forty minutes across endless landscapes of rolling plains and scattered mesquite trees. As they arrived, Greta saw more cowboys, working horses, mending fences, and managing cattle with a competence that spoke of years of experience. “These are the German girls?” an older cowboy asked, studying them with curiosity. “They look kind of delicate for ranch work.”

“They’ll toughen up,” Henderson replied. “Germans are good workers once they learn what needs doing.”

Greta felt the weight of absurdity in her situation. German soldiers sent to work as cowboys in Texas? But as they disembarked and began to settle into their new lives, the reality became undeniable. They were no longer prisoners; they were part of a working ranch, living in bunkhouses, learning skills that had defined the American West.

The first lesson began with the transformation from Vermacht officer to Texas ranch hand, marked by the simple act of putting on American cowboy clothing. Greta looked at herself in the mirror, clad in jeans and a cowboy hat, feeling ridiculous yet exhilarated. When she stepped outside, the absurdity faded into something closer to adventure.

“All right, ladies,” Henderson called from the corral fence. “Come meet your horses.” As Greta approached the chestnut mare, she felt a mix of fear and determination. This powerful animal represented a skill she never imagined needing. Learning to ride was no gentle introduction; it was an immediate immersion into a world that required strength, balance, and courage.

“Relax your hips,” instructed Maria, a seasoned cowgirl assigned to teach the German women. “The horse can feel your tension. You got to move with the animal, not fight against it.” Greta struggled with the concept. Her military training had emphasized control and precision, but cowboy work required flexibility and trust.

As the days turned into weeks, Greta began to embrace her new life. She learned to rope cattle, manage grazing rotation, and understand the rhythms of ranch work. The physical labor toughened her body, and the satisfaction of tangible achievements connected her to the land and animals in ways her previous life never had. “You’re getting it,” Maria encouraged her during a cattle drive. “See how your horse knows what to do? You just got to suggest direction and trust her to handle the details.”

Greta’s transformation from a skeptical prisoner to a competent cowgirl unfolded gradually. She discovered that ranching was not a relic of the past but a vital part of Texas’s economy and culture. The skills she initially dismissed as primitive became a source of pride and respect. “You’ve become a real hand,” Henderson told her during the fall roundup. “Would you consider staying after the war? We’ll need workers, and you’ve proven you can do the job.”

The offer stunned Greta. Stay in America as a cowgirl on a Texas ranch? Abandon Germany for a life spent herding cattle under endless skies? “I need time to think,” she replied carefully. As winter progressed, conversations among the German women revealed that many were considering similar offers. The cowboy lifestyle, hard work but honest, had won them over.

By March 1945, as Germany’s collapse accelerated, Greta made her decision. She would accept Henderson’s offer and apply for immigration sponsorship. The choice was fraught with implications. Returning to Germany meant confronting devastation and societal judgment for surviving captivity. Choosing Texas meant embracing a new identity, one shaped by the community she had come to love.

As the war ended, Greta fully transitioned from prisoner to immigrant cowgirl. She learned to rope with expert precision, ride from dawn to dusk, and manage cattle as well as any seasoned rancher. Her German origins faded into the background as she became known as one of the best cattle handlers in the region. “Never thought I’d see the day,” Maria remarked, watching Greta expertly cut a calf from the herd. “German Vermacht officer turned Texas cowgirl.”

In 1950, five years after the war’s end, Greta stood in the barn of Double H Ranch, teaching young Texans the finer points of cattle roping. Her accent marked her as an immigrant, but her skills proclaimed her belonging. “Is it true you learned all this as a prisoner?” one student asked. “Completely true,” Greta confirmed. “I was a Vermacht supply officer, but Texas ranchers needed labor, and somehow we found common ground in cowboy traditions.”

Greta’s story exemplifies the profound transformations that can occur in the most unexpected circumstances. From a German officer who once viewed cowboys as a Hollywood invention, she became a respected member of the Texas ranching community. The journey from prisoner to rancher was unlikely, but it reflected the deep truth of Texas: that cowboys are not just historical figures or cinematic fantasies, but living professionals who maintain traditions by welcoming anyone willing to learn and work hard.

As she watched her children practice roping skills on the porch of her own ranch, Greta reflected on how completely her understanding had been overturned. This was home now, a place where she had built a meaningful life, connected to the land and the traditions that defined her new identity. The journey from skepticism to acceptance, from captivity to community, had transformed her in ways she had never imagined possible.

In the end, Greta had not just found a new home in Texas; she had become part of a living tradition that transcended borders and backgrounds, proving that the most important American traditions are those that remain flexible enough to absorb newcomers. “Real cowboys,” she had once said with disbelief, watching riders work cattle across the Texas plains. Now, she was one of them, a testament to resilience, adaptability, and the enduring spirit of the American West.