‘The Americans Said, ‘Tuna Casserole Tonight” | Female German POWs Fought for Seconds

On December 12, 1944, at Camp Wheeler in Wisconsin, a scene unfolded that would deeply impact the lives of 28 German women prisoners of war. Among them was Edelt Trout Richtor, a young woman who had served as a radio operator for the Wehrmacht Communications Unit. Just weeks prior, she had been captured near the Belgian border, and now she stood in the mess hall line, her stomach twisted in anticipation and dread. After weeks of meager rations—a thin soup and hard bread that barely kept them alive—she expected nothing more than punishment rations in the American POW camp.

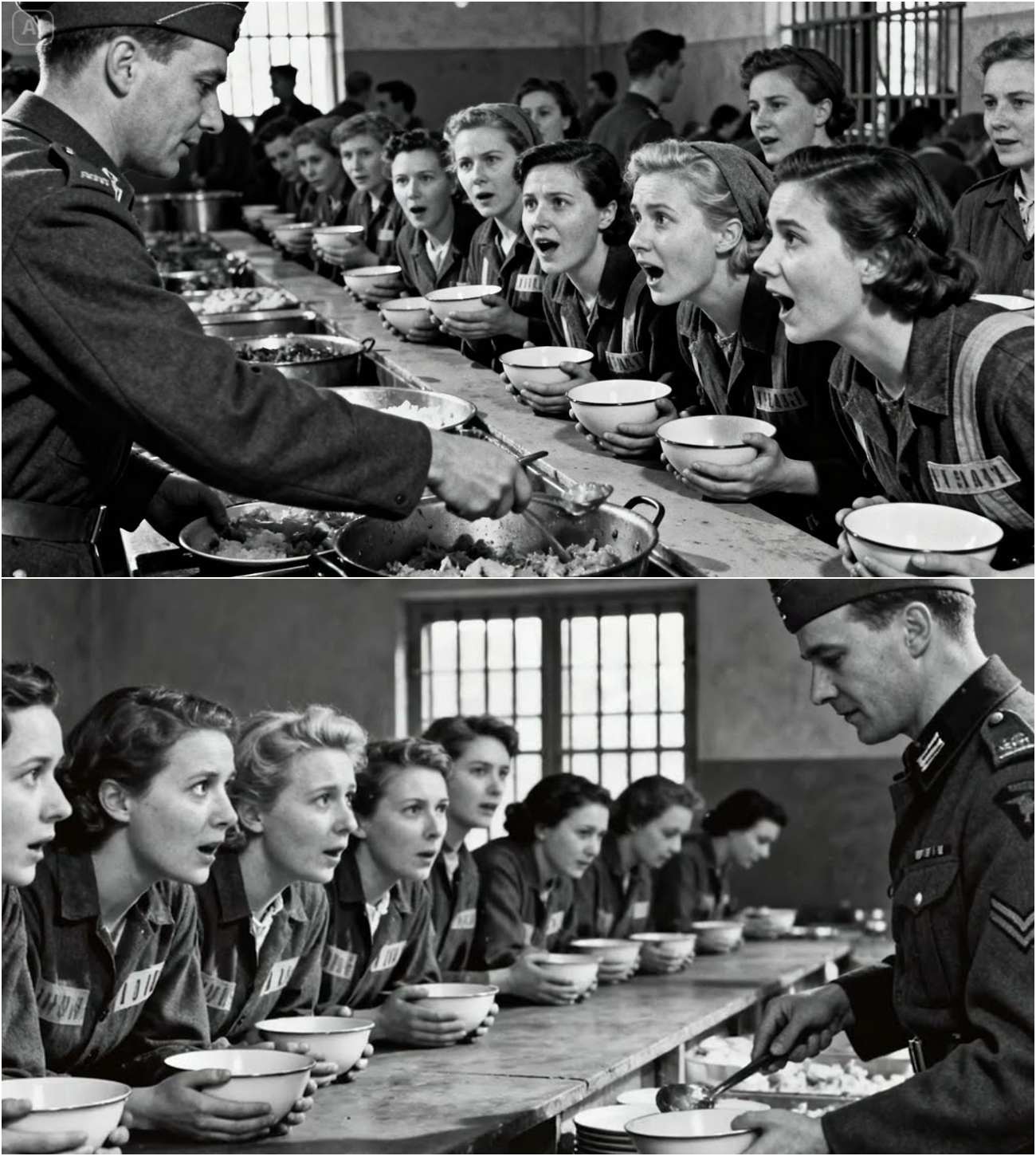

The First Taste of Abundance

As Edelt stood before the serving counter, an American soldier named Corporal Franklin Mills greeted her with unexpected cheerfulness. He served her an enormous helping of a pale yellow dish topped with crispy breadcrumbs. The portion was so large it nearly spilled over the edges of her tin plate. Confusion and disbelief washed over her and the other women. They had been conditioned to expect cruelty, not kindness, from their captors.

“Tuna casserole!” Mills exclaimed, gesturing at the food. “Good stuff! My ma’s recipe.” The women stared in frozen shock, unable to comprehend that this generous serving was meant for them. Keta Sidle, standing behind Edelt, was the first to break the spell. “This all for us?” she asked hesitantly. Mills, puzzled by the question, assured them, “Sure! Can’t have you ladies going hungry. There’s plenty more if you want seconds!”

This simple act of generosity shattered the women’s expectations. They sat down slowly, each bearing impossibly full plates, staring at more food than they had seen in months. Tears began to flow as the reality of their situation sank in. For these battle-hardened women, this moment was more than just a meal; it was a profound emotional experience.

The Weight of Hunger

To understand why a simple plate of tuna casserole could reduce these women to tears, one must grasp the depths of their hunger. Edelt had grown up in Dresden, where food was once a source of joy and comfort. However, as the war dragged on, ration cards became increasingly worthless, and the reality of starvation loomed larger. Butter became a distant memory, and meat was a rare luxury. By the time Edelt joined the Women’s Auxiliary Corps in 1943, the promise of regular meals had become a significant motivation for her enlistment.

As the war progressed, the conditions worsened. By late 1944, even military rations had deteriorated. Edelt and her unit were often left with nothing but weak coffee and a handful of dried peas. Their capture came as a relief; at least they would no longer have to endure the constant gnawing hunger that plagued them.

A Shift in Perspective

Corporal Mills, who had grown up on a dairy farm in Minnesota, brought with him a philosophy of abundance and generosity. When assigned to kitchen duty at Camp Wheeler, he quickly recognized that the standard prison rations were unacceptable. He argued passionately with Captain Ruth Gallagher, stating, “These are women who’ve been half-starved. If we feed them like this, we’ll have sick prisoners on our hands.”

Captain Gallagher authorized Mills to requisition additional supplies, and he transformed the camp kitchen into a place of nourishment and comfort. His mother’s tuna casserole became a symbol of that transformation—a simple dish meant to provide genuine sustenance and warmth.

As Edelt and the other women took their first bites, they experienced a flood of emotions. The casserole was rich and savory, filled with real tuna and soft noodles, a far cry from the barely edible rations they had endured for months. With each bite, they felt their defenses crumble. This was not just food; it was an expression of humanity, a reminder of the comfort of home.

The Thanksgiving Feast

The following day, the women gathered for Thanksgiving, an American holiday that celebrates gratitude and abundance. Captain Gallagher announced that they would share the same meal as American soldiers: turkey with all the fixings. The women were bewildered by the idea of such a feast, but as they entered the mess hall, the aroma of roasted turkey and freshly baked pies enveloped them.

Corporal Mills had worked tirelessly to prepare a spread that included turkey, stuffing, mashed potatoes, sweet potatoes, green beans, and an array of pies. The sight of the food was overwhelming. For many of the women, it was the first time they had seen such abundance in years. As they filled their plates, tears flowed freely—this was a meal that transcended mere survival.

When Captain Gallagher raised her glass of cider and expressed gratitude for the opportunity to share this meal, the emotional weight of the moment became palpable. The barriers between captors and captives began to dissolve, replaced by a shared humanity.

Breaking Down Barriers

In the days that followed, the atmosphere in the mess hall shifted. The women approached the serving line with less fear and more curiosity. They began to engage with Mills and his fellow soldiers, offering small nods of acknowledgment and attempting to communicate in broken English. This newfound connection marked a significant turning point.

Wilhelm Lang, one of the women, asked if she could help in the kitchen. Mills agreed, curious to see what would happen when the divide between server and served was blurred. Wilhelm proved to be a skilled cook, and as she worked alongside Mills, they began to share recipes and culinary techniques. The kitchen became a space of collaboration and mutual respect, where food served as a bridge between two cultures.

The Weight of Guilt

However, as the war progressed and news from Germany filtered in, the women faced a moral crisis. They received letters revealing the dire conditions their families endured back home. The contrast between their situation as well-fed prisoners and the suffering of their loved ones created an unbearable guilt. They were eating better than their own families, who were struggling to survive on meager rations.

Ute Brandt voiced the unspoken truth: “The Americans feed their enemies better than our government fed its citizens. What does that tell us about who we were really serving?” This realization weighed heavily on their hearts, complicating their feelings of gratitude.

The Revelation of Cruelty

As April 1945 approached, the women were confronted with the horrifying truth of what had been done in their country’s name. American newspapers began publishing photographs from liberated concentration camps, revealing the stark reality of systematic starvation and cruelty. The images of emaciated bodies and the accounts of deliberate deprivation shattered any remaining illusions about their own circumstances.

Edeltrout, staring at the photographs, understood with terrible clarity that while they received generous rations, countless others had been starved intentionally. The cognitive dissonance was overwhelming, leading some women to physical illness as they grappled with the implications of their situation.

A New Beginning

When Victory in Europe Day arrived on May 8, 1945, the women at Camp Wheeler greeted the news with silence. They were to be repatriated soon, returning to a Germany that had changed irrevocably. In their final conversations, the women resolved to tell the truth about their experiences. They would share the lessons learned about humanity, generosity, and the complex realities of war.

Edeltrout pulled out her notebook, filled with recipes and notes from Mills. Twenty years later, she would open a modest restaurant in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, aptly named “The Bridge.” The menu featured both German and American dishes, served side by side without hierarchy. The tuna casserole, made according to Corporal Mills’s mother’s recipe, became a signature dish—a testament to the power of shared meals.

As her daughter Anna asked about the origins of the restaurant, Edeltrout recounted her experiences in the POW camp. She explained how one man’s belief in the moral obligation to feed others, regardless of their background, had changed her life.

A Legacy of Generosity

Edeltrout’s story is a powerful reminder of the profound impact of kindness and generosity, even in the darkest of times. The lessons learned in Camp Wheeler transcended borders and ideologies, proving that shared humanity can emerge even amidst conflict.

The women who once stood in the mess hall, filled with doubt and fear, left with a renewed sense of purpose. They carried forward the belief that every meal could be an act of resistance against cruelty, a celebration of life, and a testament to the power of compassion.

In a world often divided by conflict, Edeltrout and her companions chose to remember the importance of hospitality and generosity. They understood that the act of sharing food could bridge divides, challenge perceptions, and foster understanding between even the most unlikely of allies. Their legacy lives on, reminding us all that in the face of adversity, kindness can create connections that endure long after the battles have ended.