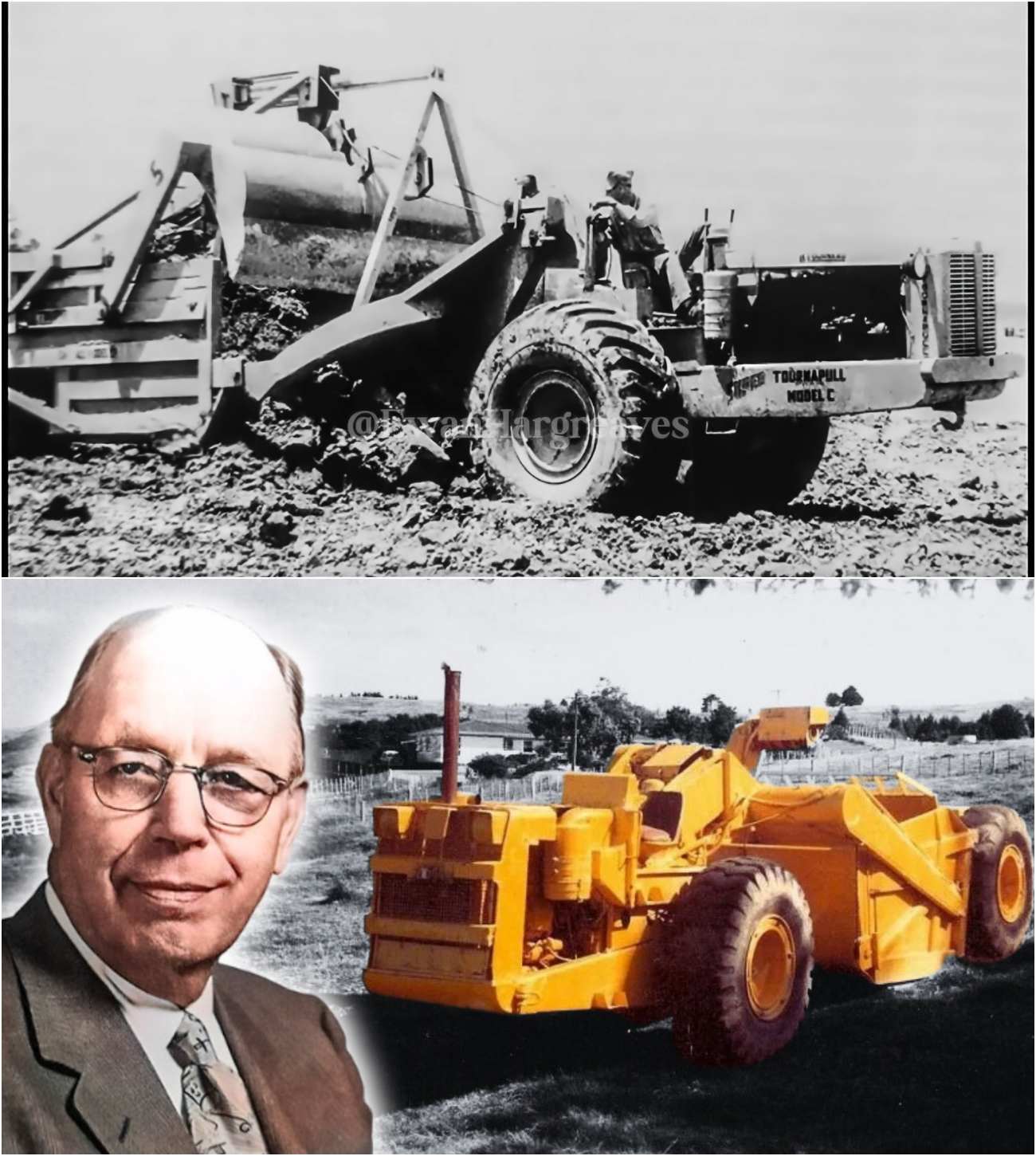

The Engineer Who Accidentally Destroyed an Entire Equipment Brand (R.G. LeTourneau)

In May of 1953, the air in a factory floor in Peoria, Illinois, was thick with the unmistakable scents of welding smoke and hydraulic fluid. Robert Gilmore LeTourneau, a man who had risen from humble beginnings to become one of the wealthiest men in America, was about to sign a deal that would change his life forever. For $31 million—equivalent to over $350 million today—Westinghouse Air Company was purchasing LeTourneau Incorporated, the earthmoving equipment empire he had built from scratch.

But what seemed like a triumphant moment was, in fact, the beginning of the end for the Leno brand, a name that had once dominated the heavy equipment industry. Within a decade, the company would be gutted, absorbed, stripped for parts, and effectively erased from the very industry it had once led. The man responsible for this unintentional destruction was none other than LeTourneau himself.

A Humble Beginning

To understand how this could happen, we must first look back at LeTourneau’s early life. Born in 1888 in Richford, Vermont, he grew up in a family that moved constantly in search of work. His father was an iron molder, and by the time Robert was a teenager, he had lived in more places than most people visit in a lifetime. School was not his forte; he barely made it through the eighth grade before dropping out. Instead of pursuing formal education, he found his passion in building and solving problems.

By the early 20th century, LeTourneau was working in auto repair shops, honing his skills in a rapidly evolving industry. In 1917, he opened his own auto repair garage in Stockton, California, but within a year, the business failed. Rather than giving up, LeTourneau realized that he had been in the wrong line of work. Instead of repairing equipment, he should be building it.

The Birth of an Empire

In the early 1920s, a local farmer needed help clearing land filled with trees, stumps, and roots. LeTourneau saw the backbreaking work involved and thought, “Why are we doing this by hand?” He rigged up a crude scraper blade behind a tractor, and though it was far from perfect, it worked. Other farmers took notice and wanted their own scrapers.

LeTourneau began building and refining his designs, creating stronger frames and better mechanisms. Then came his groundbreaking idea: what if he combined the scraper and the power unit into one self-contained machine? This was revolutionary; no one had thought to build a self-propelled scraper before. The first model was crude, but it outperformed anything else on the market, catching the attention of contractors and road builders.

By the late 1920s, LeTourneau had established a real business. He had a factory, employees, patents, and a growing customer base. However, he faced a significant challenge: his devout Christian faith compelled him to give away 90% of his income to charities and missions. This left him with little room for error; failure was not an option.

Relentless Innovation

As the 1930s progressed, LeTourneau’s scrapers became vital for major construction projects, including the Hoover Dam. But he was not satisfied. He wanted to push the boundaries further. Conventional scrapers had limitations, particularly in muddy or steep conditions. Inspired by electric drive systems used in diesel locomotives, he began experimenting with electric drive for his scrapers.

In 1937, he unveiled his first electric drive scraper. This machine could pull itself through mud and climb steep grades, unlike anything else available. While many in the industry thought he was crazy, LeTourneau’s innovations paid off. By the early 1940s, his electric drive scrapers were the most productive machines in the business.

When World War II broke out, the demand for heavy equipment skyrocketed. The U.S. military needed to move vast amounts of earth for airfields, roads, and fortifications. LeTourneau secured numerous contracts, ramping up production and hiring thousands of workers. He became one of the most important equipment manufacturers in the country, known for his relentless innovation and willingness to experiment.

The Cost of Success

However, success brought its own challenges. Manufacturing massive earthmoving equipment required enormous capital investment. LeTourneau had built a successful company but faced mounting pressures to innovate while maintaining quality. By the early 1950s, at the age of 65, he was exhausted and began considering succession.

Westinghouse Air Company approached him with an enticing offer of $31 million. For LeTourneau, this sale represented financial security for his family and the fulfillment of a promise to God that he would give away most of his wealth. He believed that Westinghouse would protect and grow the Leno brand. So, in May 1953, he signed the papers, believing he was securing his legacy.

The Unraveling Begins

What happened next was a series of missteps that would lead to the unintentional dismantling of his legacy. Westinghouse, while well-capitalized, did not understand the unique culture and innovation that had made LeTourneau Incorporated successful. They began changing the product line, cutting costs, and using cheaper materials. The machines that came out of the factories were no longer the high-quality products customers had come to trust.

As the company shifted its focus away from innovation, dealers and customers began to notice the decline in quality. LeTourneau’s loyal customer base started defecting to competitors like Caterpillar. The brand that had once been synonymous with reliability and innovation was losing its identity.

A Return to the Arena

Less than two years after selling his company, LeTourneau found a legal loophole in his non-compete agreement and founded LeTourneau Technologies, focusing on offshore drilling platforms and electric drive systems for non-construction applications. He was determined to continue innovating and competing against Westinghouse.

In May 1958, when the non-compete expired, LeTourneau launched his new line of earthmoving equipment. He took out full-page ads and personally contacted dealers, announcing his return. Westinghouse, caught off guard, attempted to sue him, but LeTourneau’s legal team easily dismissed their claims.

The new equipment he produced was superior—better designed, more reliable, and built with the innovations Westinghouse had ignored. As LeTourneau’s new company gained traction, Westinghouse’s division struggled to maintain market share. The personal relationships LeTourneau had built over decades began to pay off, as dealers returned to him, eager to sell his new machines.

The Inevitable Collapse

By the early 1960s, Westinghouse was in dire straits. They had acquired LeTourneau Incorporated with high hopes, but the brand was now faltering under their management. Despite efforts to revitalize the company, they could not compete with the innovative spirit that LeTourneau had instilled in his new venture.

In 1968, after years of declining performance, Westinghouse made the difficult decision to sell the LeTourneau division. The brand that had once been a powerhouse in the heavy equipment industry was effectively gone, absorbed into the annals of history, its innovations scattered across various owners.

The Legacy of R.G. LeTourneau

Robert Gilmore LeTourneau passed away in 1969 at the age of 81. His legacy, however, is complex. He pioneered technologies that are still in use today and built machines that moved more earth than any other manufacturer in history. He employed thousands and gave away millions, living according to his principles throughout his life.

Yet, the brand that bore his name, once synonymous with innovation and quality, faded from relevance. The story of LeTourneau is not merely a tale of success and failure; it serves as a cautionary tale about the fragility of legacy in the face of corporate greed and misunderstanding.

LeTourneau’s experience teaches us that while physical assets can be sold, the essence of innovation—the culture, the relationships, the vision—cannot be transferred so easily. When a company is too closely tied to its founder, the separation can lead to unintended consequences that ultimately dismantle the very legacy the founder sought to preserve.

In the end, the story of R.G. LeTourneau reminds us that the heart of any successful enterprise lies not just in its products but in the people who create them. As the equipment industry moved on and new players emerged, LeTourneau’s contributions to engineering and innovation left an indelible mark, even if the brand itself did not survive. His life serves as a testament to the relentless pursuit of innovation, the importance of relationships, and the complexity of legacy in the world of business.