The Final 24 Hours of FEMALE Camp Guards Of Ravensbruck

On May 2, 1945, Ravensbrück—Nazi Germany’s primary concentration camp for women—didn’t sound like a place that still believed in the future.

It sounded like paper burning.

All across the compound, the air carried a sickly haze: smoke from furnaces fed not with coal, but with files—thousands of pages that held names, orders, transfers, punishments, experiments, selections. A bureaucracy of cruelty turned into ash at the last possible second.

Outside the wire, the world was ending. Soviet forces were closing in. Artillery had been a distant rumor for days; now it was a steady drumbeat that made windows tremble and hearts misfire. The regime that had built camps like this—built them like factories—was collapsing in real time. And inside the camp, another system began to collapse just as loudly:

The system that gave female guards power over tens of thousands of women.

For years, these guards had been the unchallenged authority—uniforms, keys, whistles, batons, dogs, lists. Now, in the space of twenty-four hours, that authority turned brittle, then broke.

The hunters had become the hunted.

And what the guards did in those final hours—the lies, the panicked calculations, the sudden rewrites of history—would echo into postwar courtrooms, where the world would ask a question they could not outrun:

Who were you when it mattered?

A Camp Built to Grind Women Into Silence

Ravensbrück sat about fifty miles north of Berlin. Since 1939, it had functioned as the central detention site for women under the Nazi camp system—women deemed undesirable, dangerous, expendable: political prisoners, resistance members, Jews, Roma, and countless others swept into the machinery of incarceration.

By early May 1945, the camp’s administrative engine was still trying to behave like an engine. Orders were still typed. Roll calls still attempted. Guards still barked commands. But the sound of the war wasn’t theoretical anymore. It had teeth.

Commandant Fritz Suhren understood what that meant: evacuation wasn’t just a plan. It was a last, desperate necessity.

But moving tens of thousands of prisoners—many starving, sick, injured—while keeping control and secrecy? It was nearly impossible. And the guards knew it.

At Ravensbrück’s peak, there were around 550 female guards—a striking number, a reminder that the camp system did not run on faceless machinery alone. It ran on people. Many of these women came from ordinary backgrounds: factory workers, servants, nurses, clerks. Some joined for wages and housing. Some for ideology. Some for the status that came with holding power in a crumbling nation.

Whatever their original motive, by May 2 they faced the same prospect:

Capture. Identification. Trial. Judgment.

And for them, there was one immediate problem worse than the Soviet guns.

Unlike many defeated soldiers who might vanish into the tides of refugees, these women were known—their faces, their voices, their habits—to thousands of survivors who could point and say:

“That one.”

The Smoke of Evidence

The first priority inside the camp wasn’t mercy. It wasn’t the prisoners. It was paper.

The records department worked frantically, feeding furnaces with documents that could prove who ordered what, who signed what, who selected whom. The destruction was not random. It was organized.

The most dangerous files—those directly linking specific guards to specific atrocities—went first: personal correspondence, disciplinary records, documents listing medical experiments, execution orders, transfer lists that mapped human lives like freight.

To the guards, the smoke wasn’t just smoke.

It was insurance.

Each page burned was one less anchor tying them to what the prisoners had endured. Each file destroyed was one less rope in the courtroom.

But even as paper disappeared, another fact remained impossible to burn:

Memory.

And memory had faces.

The Women Still in Charge

Some leadership had already moved on. Johanna Langefeld—a senior figure earlier in Ravensbrück’s history—had been transferred away months before.

But in these final hours, authority among the women guards still had a name:

Maria Mandl.

Austrian-born, long associated with brutality, Mandl understood something many of her subordinates refused to say aloud: the end of the war wasn’t just a military defeat. It was moral exposure. She was recognizable. Her reputation had traveled through the camp like cold wind. Her actions—particularly her involvement in punishments and selections—had made her the kind of figure prosecutors would not ignore.

Mandl’s problem was that she had spent years training others to fear consequences.

Now consequence was walking toward the camp in Soviet boots.

May 1st Night: The Guards Begin to Split

As darkness fell on May 1, the guard quarters became hives of whispered strategy.

The hierarchy that had once kept them unified began to dissolve. Women who had enforced discipline for years suddenly looked at one another with suspicion, bargaining, resentment, and quiet panic. Alliances formed and broke in hours. Some women stared at maps like they were holy texts. Others packed small bags with whatever they believed would be valuable in a world where uniforms meant death.

Two instincts fought inside them:

Flight—disappear, blend in, live.

Performance—stay, cooperate, claim innocence, survive by narrative.

And then there was a third instinct, colder than both:

Erasure—burn everything, including the self, if necessary.

One of the most feared guards, Dorothea Binz, was not paralyzed by indecision. Young—only 24 in the account you provided—Binz approached the end like she approached her work: methodically.

She destroyed personal items that might connect her to what prisoners later described: selections, punishments, brutality. She gathered civilian clothing and false papers prepared in advance—proof that for some guards, escape planning wasn’t a last-minute impulse. It was a contingency built into their lives.

Binz’s plan was simple:

Shed the uniform. Adopt a new identity. Melt into the chaos.

The bitter irony was hard to miss: in these final hours, some guards depended on underground networks—connections, black market channels, forged papers—the very kinds of hidden systems occupiers and camp staff spent years persecuting.

When the world flips, survival often borrows from the people you once tried to crush.

Not all chose Binz’s path.

Some believed they could simply go home.

Greta Bösel, a senior guard in the transcript, represented that kind of calculation—return to family, rely on the chaos, hope that being a woman, being “administrative,” being “not directly involved” would soften what came next.

And then a smaller group made the most dangerous choice of all:

They chose to stay.

Led by a senior guard described as Elisabeth (or Elizabeth) Clem, they convinced themselves that cooperation might buy leniency. They leaned on legal language—Geneva Convention, “prisoner of war treatment”—as if semantics could protect them from what Ravensbrück actually was.

That night, in whispered conversations, the rationalizations poured out like prayers:

“I was just following orders.”

“I tried to help when I could.”

“I had no choice.”

“We maintained order.”

Even with the regime collapsing, many still spoke of prisoners using dehumanizing language, as if cruelty was still an administrative function.

And the most disturbing thing wasn’t that they lied.

It was how practiced the lies were—how easily they slid into place, like uniforms for the soul.

May 2nd Morning: Authority Becomes a Costume

May 2 dawned with a silence that didn’t feel peaceful. It felt like the moment after a door shuts and you realize the room is locked.

Roll call was chaotic. Guards were missing. Posts were empty. Orders were shouted and ignored. The chain of command that had once been rigid now looked like a frayed rope.

Suhren issued final evacuation orders: march prisoners away from the advancing Soviet forces.

But it was too late. The camp infrastructure was collapsing. Too few guards remained. Too many prisoners were too weak to move. The roads outside were clogged with refugees and retreating German units. The evacuation plan existed on paper—just like everything else.

And paper was burning.

Inside the camp’s makeshift hospital, hundreds of prisoners were too sick to march. Guards in those sections faced choices that revealed who they were without the comfort of hierarchy. Some abandoned their posts. Others tried to maintain order, but their efforts were fragile, almost theatrical—authority without the machine behind it.

Mandl, still nominally in charge of the women guards, spent the morning wrestling with crisis after crisis—women refusing to report, women openly discussing escape, women ignoring her commands. The fear that once kept everyone obedient had shifted direction.

The guards weren’t afraid of their superiors anymore.

They were afraid of the future.

The Evacuation: The Camp Spills Into the World

By early afternoon, columns began leaving Ravensbrück: roughly 2,000 prisoners in the first group, guarded by around 50 female guards—a far weaker ratio than the camp usually maintained.

On the road, the camp’s artificial order became even more exposed.

Prisoners collapsed. The weak fell behind. The roads filled with bodies and debris and desperate people moving in every direction. Some guards committed final acts of cruelty—beatings, shootings—treating the march like the last stage of their authority.

Others showed restraint—not out of repentance necessarily, but because they understood a brutal truth:

Soon, prisoners would become witnesses.

And witnesses would be believed.

The march also became a place for betrayal.

Guards began accusing each other in whispered conversations during rest stops. Years of camp culture—competition, reporting, advancement at someone else’s expense—turned into survival strategy.

The solidarity that once allowed them to function as a unit dissolved into individual desperation.

One telling example in your transcript describes a supervisor, Ruth Nöck (spelled various ways), abandoned by subordinates who used her commitment to “duty” against her. They slipped away when the column reached remote areas, disappearing into the dark like water leaking through fingers.

Other guards attempted something even more grotesque: sudden kindness.

They offered food or water to prisoners they had previously tormented, trying to buy future testimony. The power dynamic flipped so fast it was almost surreal. Women who once decided who lived and who suffered now tried to negotiate survival with crumbs.

Some even attempted to invent entire new identities—claiming they had been forced participants, secret resistance members, or carrying invented diaries meant to implicate colleagues while saving themselves.

It was not just lying.

It was history being rewritten in real time by the people most desperate to escape it.

May 3rd: Liberation, Confusion, and the First Pointing Fingers

By the time Soviet forces arrived, Ravensbrück was no longer a functioning camp. It was a wreckage field—scattered prisoners, scattered guards, scattered evidence.

The liberators were hardened soldiers, but the scale of what they found still shocked them: devastation, starvation, testimony that arrived in broken voices and trembling bodies.

Identifying guards became an urgent priority, and survivors played a crucial role. Even as many prisoners were weak or traumatized, recognition cut through fatigue.

Uniforms helped. But some guards had already stripped theirs off—civilian clothes, false papers, even attempts to disguise themselves as prisoners.

Those disguises often failed for a simple reason:

Guards looked different.

They were not the same bodies. Not the same hollow faces. Not the same skin stretched over bone.

And most of all, their faces were known.

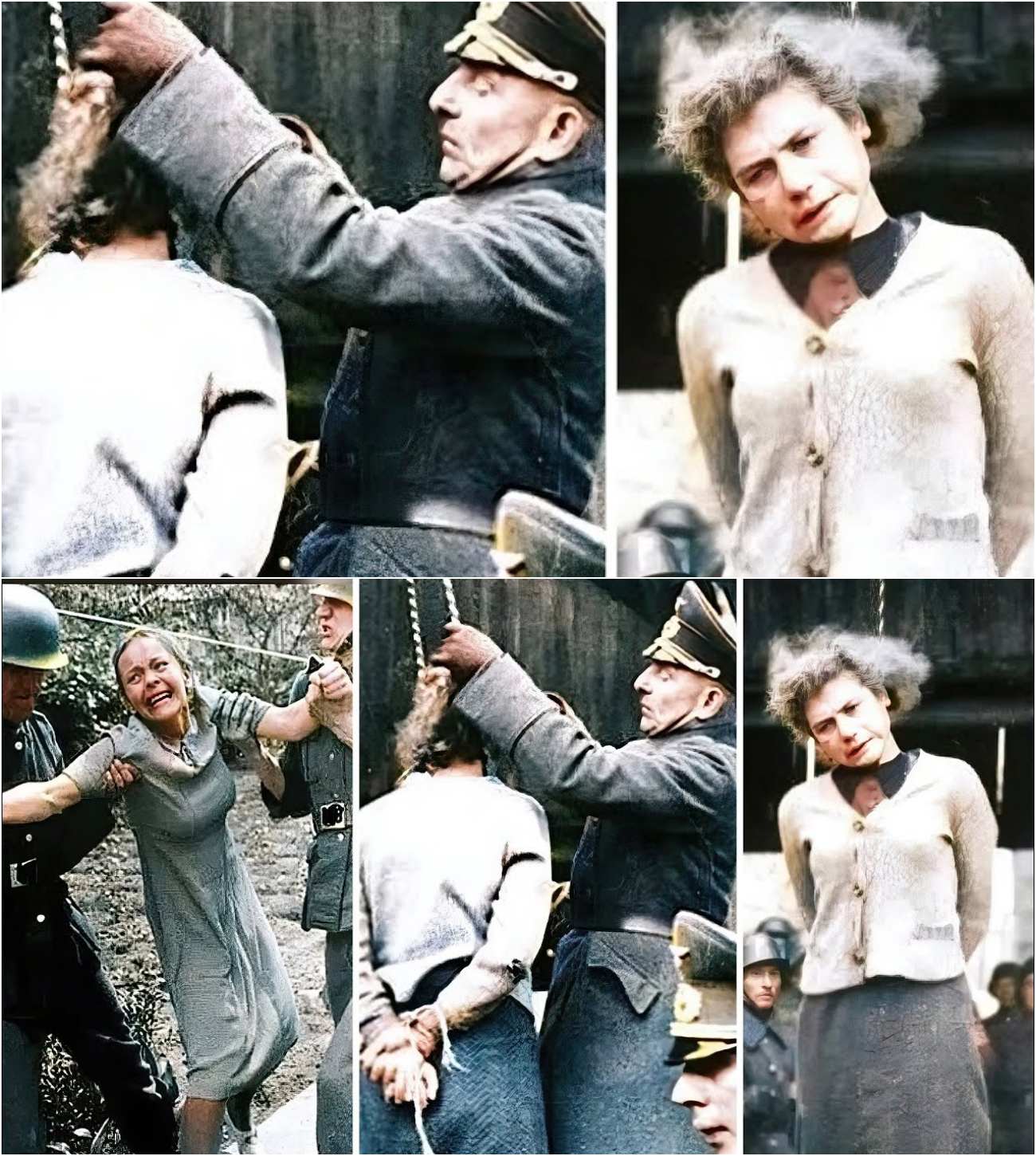

In the transcript’s account, Maria Mandl was captured dramatically—found hiding in a barn near the camp, wearing civilian clothes and carrying false documents. She claimed she was a displaced person.

But survivors recognized her immediately.

False papers can fool a checkpoint.

They cannot fool the people whose lives you controlled.

The Reckoning Begins: Trials and the Collapse of “Just Following Orders”

In the aftermath, interrogations began quickly. The testimonies were a familiar mix: denial, blame-shifting, selective memory, moral fog. Some guards tried to cooperate, but often in ways designed to reduce their own culpability by offering up colleagues.

The story did not end at liberation.

It moved into courtrooms.

The transcript references a British military tribunal in 1946, where former Ravensbrück staff—including women guards—faced charges and survivor testimony punctured the defenses that had been rehearsed in those final hours.

Again and again, claims of ignorance or coercion collided with documentation and witness accounts describing active participation—and sometimes personal zeal.

The legal principles hardened: “following orders” would not erase responsibility.

And that, ultimately, is why the last 24 hours matter.

Because the collapse of Ravensbrück didn’t just reveal panic. It revealed knowledge.

The burning of documents showed they understood what they had done was criminal.

The false identities showed they understood accountability was coming.

The sudden kindness showed they understood prisoners had power now—power of testimony, power of recognition, power of truth.

And the most chilling part is this:

Many of these women were not supernatural monsters dropped from another planet.

They were ordinary people who stepped into a system that rewarded cruelty, normalized dehumanization, and gave them the intoxicating drug of power—until the war ripped the bottle away.

In the end, the camp’s final hours weren’t just a story about guards trying to escape.

They were a story about what happens when an institution of atrocity loses its uniformed certainty, and the individuals inside it realize they can no longer hide behind the words:

“I was only doing my job.”

Because history, finally arriving at the gate, was demanding a different sentence:

“Tell us what you chose.”

If you want, I can write an even more “American true-crime documentary” version—more cinematic scene cuts, punchier hooks, and harder cliffhanger pacing—while keeping the facts limited strictly to what’s in your transcript.