The Inbred Sisters Who Kept Their Father Chained in the Cellar—Byrd Sisters’ Horrible Revenge (1877)

The Inbred Sisters Who Kept Their Father Chained in the Cellar—Byrd Sisters’ Horrible Revenge (1877)

In the remote Tennessee hills of 1877, where hollows run so deep that screams vanish into mountain fog, there existed a place called Cutters Gap, a settlement of barely 120 souls, scattered across Homestead, so isolated that evil could flourish for 14 years without interruption.

The story I’m about to tell involves sisters who took terrible revenge on their own father, chaining him in a cellar beneath their feet. But what led these young women to such an unthinkable act? In January of that year, when a federal surveyor stumbled through a blizzard seeking shelter, he heard males screaming beneath the floorboards while three calm sisters served him cornbread and acted as if nothing was wrong.

What investigators discovered in that cellar would horrify even the most hardened lawman. Yet the evidence they unearthed, hidden journals, twisted scripture, and testimony from those who chose silence, revealed a horror that made the sister’s revenge seem almost merciful by comparison. How does a respected mountain patriarch transform into something monstrous? What drives daughters to become their father’s jailers? And what truth documented in 127 pages of desperate handwriting finally brought justice after nearly 15 years of suffering? The answer will test everything you believe about family,

faith, and the terrible choices people make when law cannot reach them. Tell me in the comments where you’re watching from. And if you’re brave enough for this journey, subscribe so you don’t miss stories that reveal the darkest corners of human nature. January 23rd, 1877, began as the worst blizzard eastern Tennessee had seen in 30 years.

Federal land surveyor Nathaniel Hobbes, 29 years old and far from his Massachusetts home, lost his bearings in the white out conditions while mapping property boundaries in Siquatchi Valley. The temperature had dropped to 6° below zero. His horse had gone lame three miles back. When he saw smoke rising from a hollow, accessible only by a narrow pass between limestone cliffs, he followed it with the desperation of a man who understood he would freeze to death if he didn’t find shelter within the hour.

What he found instead would haunt him for the rest of his life and set in motion an investigation that would expose one of Tennessee’s most horrifying family secrets. The Bird Homestead sat in a clearing surrounded by trees so dense they created perpetual twilight even at midday.

The cabin itself appeared well-maintained with a stone chimney producing steady smoke and a barn that suggested working livestock. Hobbes later documented in his official affidavit that his first impression was of surprising domestic order for such an isolated location. He knocked on the heavy oak door, already rehearsing his request for shelter.

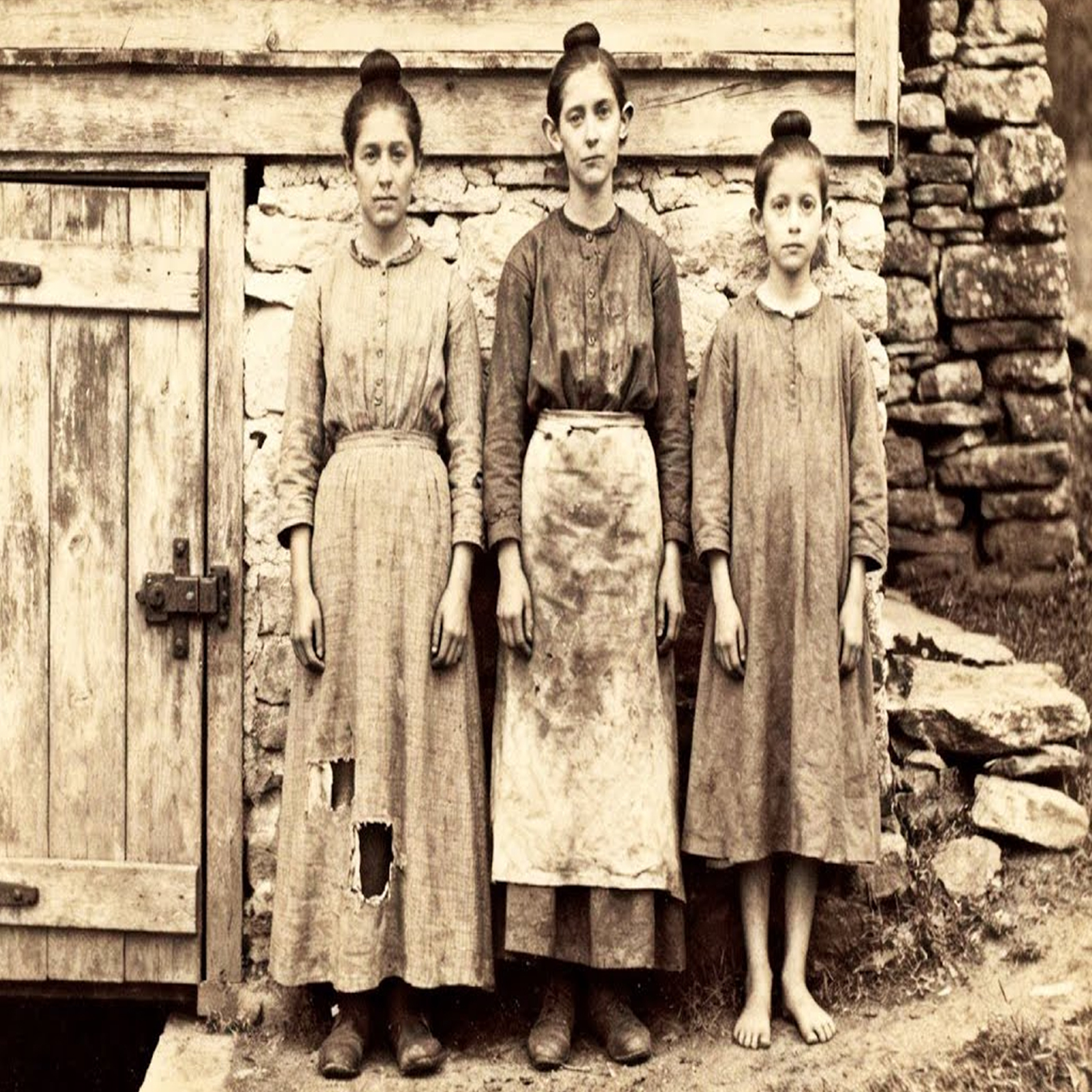

The door opened to reveal three women in their 20s, dressed in clean but patched calico dresses, their hair pinned back in the style of mountain women. The eldest, who would later be identified as Mercy Bird, aged 26, smiled at him with unsettling calm and invited him inside without hesitation. Hobbes wrote in his survey notes that evening that something about their immediate hospitality felt wrong, though he couldn’t articulate why.

The interior was warm, clean, and smelled of baking cornbread. The three sisters moved about the kitchen with practice efficiency, setting a place for him at their table. Then he heard it, a male voice screaming from beneath his feet. Not words exactly, but raw sounds of distress that made Hobbs freeze with his hand halfway to the cornbread they’d placed before him.

The screaming continued for perhaps 30 seconds, then dissolved into sobbing, then silence. Hobbes looked at the three women. They continued their domestic tasks as if nothing had happened. The eldest sister, Mercy, met his eyes and said in a voice devoid of emotion, “That’s just papa. He’s not well.” Hobbs asked what was wrong with their father.

Temperance, age 23 and walking with a pronounced limp from a club foot, simply said, “He’s being cared for.” The youngest, Clarity, age 13, but looking older from hardship, said nothing at all. When Hobbes pressed further, asking if their father needed a doctor, Mercy replied with chilling precision. He’s had 14 months to think about whether he needs anything.

We’ll ask him again tomorrow. The screaming resumed throughout that endless night. Hobbes later testified in his deposition that he heard chains dragging across stone, muffled begging that sounded like prayers, and at one point a man’s voice shouting biblical passages with wild desperation.

Each time the sounds grew too loud, the sisters would begin singing hymns in threepart harmony, their voices rising to drown out whatever was happening in the darkness below. Hobbes documented in his official survey report that he pretended to sleep while memorizing every detail of the cabin’s layout, noting particularly a trap door in the kitchen corner covered by a woven rug.

He observed that the sisters moved around this spot with careful precision, never stepping directly on it, as if long habit had taught them to avoid the exact location of whatever lay beneath. When dawn finally broke, Hobbes thanked them for their hospitality with a politeness that barely masked his horror.

Mercy walked him to the door and said something he would repeat in courtroom testimony 14 months later. You seem like a good man, Mr. Hobbes. Good men sometimes find things they weren’t looking for. We’ll be here when you come back. The 23mm journey back to the nearest settlement took Hobbes 2 days through snow that had drifted to 4 feet in places.

He went directly to the federal marshall’s office in Knoxville rather than to local authorities, later explaining that he sensed mountain people would not act on what he’d witnessed. Deputy US Marshal Owen Guthrie, 41 years old and a former Union cavalry scout, who knew Tennessee’s mountain regions intimately listened to Hobbes’s account with the stillness of a man who had seen too much evil to dismiss any claim as implausible.

Guthri’s service records showed he’d built a reputation for pursuing cases in isolated areas that other lawmen considered too remote or too tangled in mountain customs to investigate. He asked Hobbes three questions. Were the women in immediate danger? Was the man in the cellar alive? Could Hobbs lead him back to the location? When Hobbes answered yes, yes, and yes, Guthrie began assembling supplies for an investigation into territory 47 mi from the nearest county seat, where Tennessee law barely reached, and family matters were considered sacred and untouchable.

3 weeks passed before weather permitted the journey back to Cutters Gap. During that time, Guthrie researched the Bird family through county land records and spoke quietly with the few mountain people who came to town for supplies. What he learned suggested a family that had withdrawn from all community contact after the death of matriarch Abigail Bird in 1863.

Ezekiel Morai Bird, age 52, had once been known as Brother Ezekiel, hosting Sunday prayer meetings and serving as informal counsel for disputes. After his wife’s death during childbirth, he’d closed his home to visitors and forbidden his four daughters from attending community gatherings.

Neighbors described this as griefdriven, but not unusual for mountain families who valued privacy above all else. No one had seen any of the bird daughters in town for over a decade. No one had thought this strange enough to investigate. Mountain Code dictated that what happened on a man’s property was his own business, and interference was considered worse than whatever sin might be hidden.

February 14th, 1877, Marshall Guthrie and surveyor Hobbes arrived at the bird homestead under clear winter skies that made the isolation even more apparent. Guthri’s official investigative affidavit preserved in Tennessee State Archives as case file number 1878 CR047 describes approaching the property with acute awareness that whatever happened in this hollow could vanish into mountain silence if not properly documented.

The three bird sisters greeted them at the door with the same unsettling calm Hobbes had witnessed three weeks earlier. Mercy invited them inside, offered coffee, and asked without preamble whether they had come about her father. When Guthrie confirmed this, she said simply, “We’ll show you. We’ve been waiting for someone with authority to see.

” Her use of the word authority struck Guthrie as deliberate, as if she understood the distinction between federal law and mountain custom. She led them to the kitchen corner, where the woven rug covered the trap door Hobbs had noticed during his first visit. Temperance pulled back the rug to reveal a wooden door secured with a heavy iron bolt.

The bolt showed no rust despite the cabin’s dampness, suggesting frequent use. When Mercy drew back the bolt, the sound of chains rattling came immediately from below, followed by a man’s voice croaking. Thank God. Thank God. Federal men, I heard you talking. My daughters have gone mad. They’ve kept me prisoner. You must arrest them. Guthrie descended the ladder into darkness that his lantern barely penetrated.

The affidavit he filed four days later contains 23 pages of meticulous documentation. But the first paragraph captures the horror in clinical language that somehow makes it worse. Subject discovered chained by neck iron and ankle restraints to limestone wall of root cellar measuring approximately 8 ft by 12 ft.

Subject in state of extreme malnourishment and poor hygiene living in own waste. Seller temperature estimated 38°. Evidence suggests prolonged imprisonment. The man chained to the wall was Ezekiel Morai Bird, though Guthrie wrote that he initially doubted this identification because the figure before him appeared closer to 70 than 52. Bird’s hair and beard had grown wild, matted with filth.

His clothes were rags. The chain securing him allowed perhaps 4 feet of movement from the wall, enough to reach a waste bucket and a wooden bowl containing what appeared to be vegetable scraps and stale cornbread. Guthrie documented that the neck iron was secured with a padlock for which the sisters kept the key on a leather cord hanging in the kitchen above.

The ankle chains were fastened directly into the limestone with iron spikes driven deep into rock. When Guthrie asked how long Bird had been imprisoned, the voice from above the trapdo answered before Bird could speak. Mercy stated flatly, “14 months, 2 weeks, and 3 days. We counted carefully.

” Bird began shouting that his daughters were insane, that isolation had broken their minds, that he’d been a godly father who’d done nothing to deserve such treatment. He quoted scripture as he spoke, citing passages about children honoring fathers and patriarchal authority under divine law. Guthrie noted in his affidavit that Bird’s ability to recite lengthy biblical passages suggested his mind remained sharp despite his physical deterioration.

The marshall climbed back up to question the sisters, leaving Hobbes to document the cellar with detailed sketches that were later entered as evidence. mercy, temperance, and clarity sat at their kitchen table and answered every question with disturbing precision. When Guthrie asked why they had imprisoned their father, Mercy said, “For what he did to prudence, for what he did to all of us.

” When pressed to explain, she added, “Our mother died birthing clarity in November 1863. After that, Papa said we had to be his wives in all ways. He said isolation meant different rules, that mountain law wasn’t town law, that Abraham had wives, and so did Jacob. The casual way Mercy delivered this information made Guthri’s stomach turn.

His affidavit notes that all three sisters showed physical anomalies he recognized from his years in isolated mountain communities as potential markers of inbreeding. Mercy was partially deaf in her left ear, a condition she attributed to an untreated childhood infection, but which showed characteristics consistent with hereditary defects. Temperance’s club foot was severe enough to make walking difficult.

Clarity, the youngest, appeared frail and breathless from minimal exertion. When Guthrie asked directly whether their father had forced himself upon them, all three nodded. When he asked if this had resulted in pregnancies, Mercy said, “Prudence bore two stillborn twins in 1868. She had another baby in 1870 who lived 3 days.

She died in November 1875 from complications of a fourth pregnancy. Our sister is buried behind the barn. The marshall’s notes record that he asked where the other babies were buried. Temperance pointed to the same location. Guthrie added to his documentation. Sisters report father refused medical assistance for prudence’s final labor, resulting in her death age 27.

From the cellar below, Ezekiel Bird was shouting justifications that Guthrie could hear clearly through the open trap door. I kept my blood pure. I preserve the line. Abraham had Sarah and Hagar. Jacob had Rachel and Leah. The patriarchs knew that isolation required different covenant.

Mercy looked at Guthrie and said, “He’s been saying versions of that for 14 years. He truly believes God gave him permission.” When the marshall asked what prompted them to imprison their father rather than kill him outright, Clarity spoke for the first time. Her voice was soft but steady.

We wanted him to understand what it was to be owned, to be property, to have someone else control whether you ate or starved, whether you lived in filth or cleanliness, whether you suffered or found relief. We wanted him conscious and aware every single day. Temperance added, “We never struck him. We never touched him wrong. We just kept him the way he kept us.

” Guthrie began a systematic search of the homestead while Hobbes remained with the sisters. In Ezekiel Bird’s bedroom, the marshall discovered a leatherbound journal that would become prosecution exhibit C. The journal contained 89 pages of entries dating from November 1863 to October 1876, written in careful script that demonstrated education unusual for isolated mountain farmers.

Each entry documented which daughter had served what Bird called wely duties on that date, accompanied by scriptural passages he claimed justified the acts. Sample entries preserved in court records include citations of Genesis 19 regarding Lot’s daughters, references to patriarchal marriage customs, and theological arguments about bloodline preservation.

The journal’s meticulous documentation would prove Bird understood exactly what he was doing and had constructed an elaborate justification system rather than acting from ignorance or mental defect. But the most damning evidence lay hidden in the family Bible, a massive King James edition that sat on the parlor table as if placed for display. When Guthrie opened it, he discovered the interior pages had been hollowed out to create a hiding space.

Inside lay another journal, this one written in smaller, more desperate handwriting. The first page bore the name Prudence Bird and a date, November 15th, 1863. The first entry read, “Mama died today, birthing clarity. Papa says we are alone now. He says, “I must take Mama’s place in all things. I am 11 years old.

I do not understand what he means.” Guthri’s hands trembled as he turned pages, realizing he held testimony from beyond the grave. Prudence Bird had documented everything. Prudence Bird’s journal contained 127 pages of careful documentation spanning 12 years of systematic abuse. Marshall Guthrie sat at the Bird family table, reading entries aloud to establish their evidentiary value, while the three surviving sisters listened without visible emotion.

The early entries showed a child’s confusion transforming into horrified understanding. December 1863. Papa came to my room last night. He said, “Mama used to sleep with him, and now I must.” He said, “This is what the Bible means about daughters obeying fathers. It hurt very much.” I cried, but he said, “I must be silent or I would wake my sisters.” January 1864.

Papa says we cannot go to church anymore because town people would not understand mountain ways. He says we are like the patriarchs in the wilderness. That isolation means we follow older laws than town laws. The progression documented in Prudence’s handwriting showed abuse that began immediately after their mother’s death and intensified as each sister reached adolescence.

By March 1864, Prudence was documenting her father’s systematic theological justification. She recorded entire conversations where Ezekiel Bird explained his interpretation of scripture, citing Abraham’s relationship with Hagar, Lot’s daughters preserving their father’s line, and Jacob’s multiple wives as biblical precedent for what he termed patriarchal covenant in isolated circumstances.

Prudence wrote, “Papa says Abraham was willing to sacrifice Isaac because a father owns his children under God’s law. He says we belong to him the same way Sarah belonged to Abraham.” I looked up these stories in Mama’s Bible. I do not think Papa is reading them correctly, but I am only 12 and he says, “Children cannot question fathers.” Court records show that Dr.

Horus Apprentice, the county physician who later examined the journal, testified that Prudence’s literacy and analytical thinking demonstrated intelligence that made her documentation particularly credible. She wasn’t simply recording events, but questioning the theological framework her father used to justify them.

The journal’s middle years chronicled Ezekiel’s expansion of abuse to include each sister as they matured. June 1865, Papa started visiting Mercy’s room last month when she turned 14. I hear her crying through the wall. She asked me if Papa does the same to me. I told her yes. We held each other and cried. Papa heard us and beat us both for gossiping about family matters.

He said, “If we ever speak of this to each other again, he will chain us in the root cellar.” August 1867. Papa now visits Temperance, who is 13. She limps worse now, I think, from trying to run from him. He caught her attempting to hide in the barn loft. We are not permitted to speak of what happens, but we all know we are all trapped. The entries revealed that Ezekiel enforced silence between his daughters, isolating each and her suffering while maintaining complete control through threats of physical punishment and theological intimidation. Prudence’s documentation of her own

pregnancies provided medical evidence that would prove crucial to the prosecution. November 1867. My monthly courses have stopped. I am 19. I believe I am with child. Papa says this is proof God approves of our family’s ways that the child will be pure and blessed. I am terrified. The pregnancy ended in March 1868 with stillborn twins that Prudence described in detail too graphic for courtroom reading. Dr.

Apprentice’s later testimony confirmed that Prudence’s descriptions matched complications consistent with inbreeding, including severe deformities she had sketched in the journal’s margins. A second pregnancy in 1869 resulted in a daughter born in February 1870 who lived only 3 days. Prudence’s entry for the infant’s death reads, “We buried her beside the twins.

Papa said her death proved we needed to try again, that God was testing our faithfulness. I told him I could not survive another pregnancy. He said, “Women’s fears mean nothing against God’s will.” The journal’s later entries showed Prudence’s growing awareness that documentation might be her only weapon. January 1873.

I have begun recording dates and details in case someone ever finds this. Papa keeps his own records in a journal he hides in his room. If there is ever justice for what happens here, there must be proof. Mountain people do not believe women’s words without evidence. She began noting specific dates of abuse, correlating them with her sister’s visible injuries and emotional states. April 1874. Clarity is now 10.

Papa has not touched her yet, but I know he will soon. She still has some innocence left. I try to protect it, but I know I cannot. October 1875. I am with child again. My body is giving out. I am 27 but feel 60. Mercy says we must do something after I am gone. I told her where I hide this journal.

I made her promise to find a way to make Papa answer for what he has done. Prudence’s final entries were dated November 1875, 2 days before her death from pregnancy complications that Ezekiel refused to treat with medical care. She wrote, “I am dying. I can feel it. The baby inside me is killing me, and I am glad because it means escape. But my sisters will remain trapped. Mercy is strong.

Temperance is clever. Clarity is young but braver than she knows. I have told them where this journal is hidden. I have told them everything is recorded here. Every date, every act, every justification papa used. If anyone ever reads this, no, we were not wicked. We were only trying to survive. Tell our story so no girl suffers alone.

The final line was barely legible, as if written with failing strength. Make him pay for what he has done to us. Marshall Guthy’s affidavit records that after reading these entries, he immediately requested Dr. Apprentice travel from the county seat to conduct medical examinations of all three surviving sisters.

The doctor’s report completed over two days in February 1877 and preserved as prosecution exhibit Dced physical evidence consistent with Prudence’s timeline. Mercy showed scarring consistent with sexual trauma beginning in adolescence, partially healed fractures in her left hand from a beating Prudence had documented in 1866, and the hearing loss in her left ear that medical examination suggested resulted from repeated head trauma rather than simple infection.

Temperance’s clubfoot showed evidence of having been broken and poorly healed, matching Prudence’s 1867 entry about Ezekiel catching her trying to flee. Clarity, though youngest, showed signs of malnutrition and a heart murmur that Dr.

apprentice noted in his report as consistent with hereditary defects observed in isolated populations practicing consanguinous reproduction. The doctor’s examination also documented evidence that all three sisters had been pregnant at some point, though Mercy and Temperance’s pregnancies had ended in early miscarriages they had never mentioned. Dr.

apprentice wrote in his medical opinion, “These women bear physical evidence of prolonged sexual abuse beginning in early adolescence. The hereditary conditions present in all three sisters suggest genetic impact of inbreeding. Their psychological state shows trauma but not insanity. They demonstrate clear memory, logical thought progression, and appropriate emotional response to extreme circumstances.

They are victims who survived through extraordinary resilience, not perpetrators who acted from mental defect. This medical testimony would prove essential when the case went to trial, establishing that the sisters had acted from rational response to intolerable circumstances rather than from derangement or malice.

Guthri’s investigation expanded to locate witnesses who might corroborate the journal’s timeline. He found Bethany Crockett, the midwife who had attended Prudence’s failed pregnancies in 1868 and 1870. Now 52 years old, Crockett initially refused to speak with the marshall, citing Mountain Code about family privacy.

Only when Guthrie read her selected passages from Prudence’s journal did she break down and confess what she had witnessed and chosen to ignore. Bethany Crockett’s testimony documented in a sworn affidavit taken March 1877 and preserved in the trial records revealed the community’s collective failure to act on visible evidence of abuse.

The midwife described attending Prudence’s labor in March 1868 when the young woman was barely 19 years old and already bearing twins conceived through her father’s abuse. Crockett testified, “I knew something was terribly wrong the moment I entered that house. Prudence was near death from complications.

The other girls mercy and temperance were too quiet, too fearful. They moved like whipped dogs. When I examined Prudence, I saw bruising on her body that had nothing to do with childbirth. The twins were born dead, both showing deformities I recognized from other cases of blood relatives breeding.

The midwife admitted that Ezekiel Bird paid her double her normal fee, and said plainly, “You’ll forget what you’ve seen here, or you’ll never work in these mountains again. Crockett took the money and kept silent, a decision that would haunt her for the rest of her life. The midwife returned in February 1870 for Prudence’s second labor, which resulted in a daughter who survived 3 days before dying from what Crockett recognized as congenital heart defects associated with inbreeding.

She described the infant in her testimony with clinical precision that made the horror worse. The baby girl had a mullformed heart valve, eyes set too wide, fingers that wouldn’t uncurl. I knew what caused it. I’d seen it before in isolated mountain families where cousins married cousins for generations. But this was different.

This was a father and daughter. I watched that baby struggle for breath for three days while Ezekiel Bird prayed over her, calling her death God’s testing of his faith. When Prudence begged Crockett to help them escape, to tell someone what was happening, the midwife refused. She testified, “I told myself it wasn’t my place to interfere in family matters.

Mountain Code said, you don’t break up families even when something’s wrong. I took his money again. I left those girls to suffer. I will answer to God for that cowardice. With Crockett’s testimony establishing a pattern of community knowledge and deliberate silence, Marshall Guthrie focused his investigation on understanding exactly how the sisters had turned the tables on their abuser.

Mercy Bird provided a detailed account that Guthrie transcribed over 6 hours of questioning in late February 1877. She explained that after Prudence’s death in November 1875, the three surviving sisters held a council in the barn where their father couldn’t hear them. Temperance described the planning session in her own testimony. We knew clarity would be next.

She was 12 and Papa had started watching her the way he’d watched each of us before he began. We couldn’t let Prudence’s death be meaningless. She documented everything so there would be proof. We decided Papa needed to understand what it meant to be property to be owned to have no control over your own body or life.

The sisters spent nearly a year preparing their revenge with calculated precision that demonstrated clear minds and deliberate intent. Mercy explained they needed to wait until they were certain of their method and timing. They couldn’t kill their father outright because that would bring immediate legal consequences without opportunity to expose his crimes. They needed him alive to face justice.

But they also needed him to experience the helplessness he’d inflicted on them. October 1876 marked the anniversary of Prudence’s final pregnancy, the one that killed her. The sisters chose this date deliberately. Temperance had been studying their mother’s herb garden, identifying plants Abigail Bird had taught them about before her death.

Fox glove grew wild near the creek, a plant their mother had warned them could heal in small doses or harm in larger ones. Temperance testified, “I calculated the dosage carefully, enough to make Papa unconscious, but not enough to kill him. We wanted him aware of what was happening. Death would have been mercy he didn’t deserve.

” On the evening of October 28th, 1876, the sisters prepared their father’s meal as usual. Mercy added fox glove tea to his coffee, disguising the bitter taste with honey from their hives. Ezekiel Bird consumed his meal while reading scripture aloud, as was his custom, lecturing his daughters about obedience and patriarchal authority.

Within 20 minutes, he began showing signs of the drug’s effect. Dizziness, confusion, slurred speech. Clarity testified about watching her father realize something was wrong. He looked at us and said, “What have you done?” Mercy told him, “What you taught us to do?” We obeyed. He tried to stand but collapsed. We caught him before he hit the floor, not out of love, but because we needed him conscious for what came next.

The sisters dragged their semi-conscious father across the kitchen floor to the root cellar trap door. Combined, the three women weighed perhaps 300 lb total. Ezekiel Bird weighed close to 200 lb. It took them nearly an hour to maneuver his body down the ladder into the cellar.

The chains they used to secure him were the same chains Ezekiel had used to threaten them throughout their lives. He kept them hanging in the barn, occasionally bringing them into the house to demonstrate what would happen if they ever disobeyed or tried to run. Mercy described how they’d planned the restraint system. We knew exactly how much movement to allow him.

4 ft from the wall, enough to reach a waste bucket, and a food bowl, enough to lie down or stand, but not enough to reach the ladder or attempt escape. We used the neck iron he had threatened us with for years. We drove the ankle chains into the limestone with his own blacksmithing tools. When Ezekiel regained full consciousness hours later and began screaming, the sisters were sitting at the kitchen table directly above the cellar, eating the remainder of the meal they drugged. Temperance testified that they’d discussed what to say when he woke. They

decided on silence. We wanted him to feel what we’d felt, the terror of realizing no one was coming to help. That pleading changed nothing. that the person who controlled your life felt no mercy. For 14 months, two weeks, and three days, the Bird sisters maintain their father’s imprisonment with methodical care that proved their actions stemmed from calculated justice rather than impulsive rage.

They fed him once daily, providing the same portions he’d given them during what he called discipline periods when they displeased him. Stale bread, vegetable scraps, water. Mercy kept a written record of every feeding, creating documentation that mirrored her father’s meticulous journal of abuse. She testified, “We wanted proof that we kept him alive deliberately.

This wasn’t murder. This was imprisonment. We made sure he had enough to survive, but not enough to be comfortable. The sisters emptied his waste bucket twice weekly, forcing him to live in conditions that grew increasingly foul between cleanings. They provided no blankets despite the seller’s winter cold, reasoning that he’d never shown concern for their comfort.

Most significantly, they made him listen every single night as they prayed aloud for Prudence’s soul, their voices carrying clearly through the floorboards to the darkness below. The psychological torture proved more devastating than physical deprivation. Clarity testified that her father’s responses evolved over the months of imprisonment. Initially, he raged, shouting threats and biblical justifications.

By spring 1877, he was bargaining, promising to let them go free if they released him, swearing he’d never touch them again. By summer, he was weeping, begging for mercy, claiming to repent. But the sisters recognized these tactics as variations of the manipulation he’d used throughout their lives. Mercy stated in her testimony, “Papa was very good at saying whatever kept him in control.

We’d heard every version of his promises before. We knew they meant nothing. So, we kept him chained, and we kept counting the days, waiting for someone from outside to finally see what had been hidden in this hollow for 14 years.” The trial of Ezekiel Morai Bird began April 15th, 1878 in Ria County Circuit Court before Judge Amos Whitfield, a 61-year-old jurist who had presided over 39 years of Tennessee’s most difficult cases.

The courtroom in the county seat was packed beyond capacity with over 200 spectators, many having traveled days from surrounding counties after newspapers across the state published details of the case. The Knoxville Daily Tribune’s coverage called it the most disturbing family crime in Tennessee history.

A case that forces examination of how isolation enables evil and silence becomes complicity. Ezekiel Bird sat in the defendant’s chair wearing clean clothes provided by the county jail. His appearance dramatically improved from the emaciated creature Marshall Guthrie had found in the cellar 15 months earlier.

His lawyer, Marcus Thornton, had accepted the case reluctantly after three other attorneys refused, understanding that defending Bird meant professional reputation damage regardless of outcome. The prosecution was led by District Attorney Samuel Brennan, who opened with a strategy that would become legendary in Tennessee legal history.

Rather than beginning with sensational testimony about the seller imprisonment, he started by reading aloud from Prudence Bird’s journal. The courtroom fell silent as Brennan read the first entry. November 15th, 1863. Mama died today, birthing clarity. Papa says, “We are alone now.” He says, “I must take Mama’s place in all things.

I am 11 years old. I do not understand what he means.” The prosecutor read chronologically, allowing Prudence’s voice to build the case entry by entry, year by year, pregnancy by pregnancy. Court records show that multiple women in the gallery wept openly.

Several men left the courtroom appearing physically ill. Judge Whitfield maintained stern composure, but was observed wiping his eyes when Brennan reached Prudence’s final entry about dying alone while documenting evidence so her sisters might find justice. After two hours of journal readings, Brennan presented Ezekiel Bird’s own scripture book as prosecution exhibit C.

The contrast between the two journals devastated any defense strategy. Where Prudence wrote with desperate hope that someone might eventually care about their suffering, Ezekiel wrote with cold calculation and theological certainty. Sample entries read into court record included, June 14th, 1864. Prudence continues to resist her duties. Applied discipline as scripture permits.

Genesis 22 reminds us Abraham was willing to sacrifice Isaac, proving children are property of the father under God’s law. My daughters belong to me by divine and natural right. Another entry from March 1866 stated, “Mercy has come of age. Began her education in wely obligations. She shows more obedience than prudence initially did.

Isolation from corrupt town influences allows proper patriarchal authority as practiced by Abraham, Jacob, and other righteous men of scripture. The meticulous dating in both journals allowed prosecutors to cross-reference entries, proving that Ezekiel documented the same acts Prudence recorded, but frame them as religious duty rather than criminal abuse. Dr.

Horus Apprentice testified for 6 hours across two days, presenting medical evidence that corroborated both journals. His examination reports, illustrated with clinical diagrams that were sealed from public viewing due to their graphic nature, documented physical proof of long-term sexual abuse, beginning when each sister reached early adolescence.

The doctor’s testimony about hereditary markers consistent with inbreeding provided scientific validation for Prudence’s documentation of pregnancies resulting from her father’s abuse. When defense attorney Thornton attempted to question the reliability of medical assessment of historical abuse, Dr. Apprentice responded with devastating precision.

Sir, I have practiced medicine for 25 years in rural Tennessee. I know what poverty looks like, what accidents look like, what natural hereditary conditions look like. What I documented in my examination of the Bird Sisters was systematic trauma consistent with their testimony and Prudence’s written record. The evidence is incontrovertible.

Marshall Guthri’s testimony established the investigative timeline and chain of evidence. His 23page affidavit read into court record over 4 hours describe discovering Ezekiel in the cellar, finding both journals, interviewing the sisters, and collecting physical evidence, including the chains, padlock, and photographs of the seller conditions.

Defense attorney Thornton attempted to discredit the investigation by arguing that Guthrie was a federal officer interfering in state family matters, but Judge Whitfield shut down this argument immediately. Council will note that incest, rape, and abuse of minors are crimes under Tennessee law regardless of whether they occur in isolated mountain hollows or on courthouse steps. Marshall Guthri’s federal authority is irrelevant to the validity of evidence he collected.

Proceed with your next question or sit down. The rebuke signaled that the judge would not permit cultural relativism to excuse documented evil. The prosecution’s most strategic decision came in presenting the chains as physical evidence. Court records show that on April 19th, the fourth day of trial, baiffs carried the neck iron, ankle restraints, and chains into the courtroom and placed them on a table before the jury.

The sound of iron striking wood echoed through the chamber. Brennan asked the jury to examine the evidence, noting the wear patterns on the chains from 14 months of use, the rust from seller moisture, and the padlock mechanism that had kept Ezekiel secured. The prosecutor then called Ezekiel Bird himself to the stand, a risky maneuver that demonstrated Brennan’s confidence in the strength of documentary evidence.

Under oath, Ezekiel was asked if he recognized the chains. He confirmed they were his, kept in his barn for livestock and equipment securing. When asked if these were the chains used to imprison him in his cellar, he confirmed this as well. Then Brennan asked the question that would seal the conviction. Mr.

Bird, had you ever threatened your daughters with these chains prior to them using them on you? Ezekiel Bird made the fatal mistake of honesty. Perhaps he believed admitting to threats seemed less damaging than the other accusations against him. Perhaps he genuinely saw nothing wrong with intimidating his daughters into obedience. He answered, “A father has the right to discipline his children.

I showed them the chains to teach them the consequences of disobedience.” Proverbs says, “Spare the rod, spoil the child.” I was teaching them godly respect for paternal authority. Brennan let this answer settle over the courtroom before asking his followup. So when your daughters chained you in that cellar, they were teaching you the same lesson you taught them about consequences and authority.

The objection from the defense was immediate but overruled. The damage was done. The jury had heard Ezekiel admit that the very instruments of his imprisonment were tools he’d used to terrorize his daughters for years. The victims had simply turned the abusers’s weapons against him. The defense strategy collapsed entirely when Thornton called Ezekiel to provide his own account of events.

The attorney had likely hoped his client would present himself as a misunderstood patriarch whose actions stemmed from religious conviction and isolation rather than criminal intent. Instead, Ezekiel’s testimony demonstrated complete lack of remorse and unwavering belief in his righteousness. When asked to explain his relationship with his daughters after his wife’s death, Ezekiel stated, “The Bible is clear that a man’s household belongs to him.

” After Abigail died, my daughters became my responsibility in all ways. I taught them obedience, discipline, and the proper role of women under patriarchal authority as practiced by Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. When pressed specifically about sexual relations with his daughters, he responded, “They were mine to do with, as I saw fit.

Isolation from corrupt towns meant we lived by older, purer laws. I preserved our bloodline as the patriarchs did.” Judge Whitfield interrupted at this point, asking directly, “Mr. bird, are you claiming divine sanction for raping your daughters from the time they were children? The defendant’s response entered court record verbatim. It was not rape, your honor.

It was patriarchal covenant. They belong to me by God’s law and natural law. Everything I did was to preserve purity and maintain proper family order. The judge’s face, described in newspaper accounts as showing barely controlled fury, darkened visibly. He allowed the testimony to continue only long enough for Ezekiel to thoroughly condemn himself.

When asked about Prudence’s death, Bird showed no emotion. The weak cannot survive childbearing. This is nature’s way. Her death was God’s will, not my responsibility. When asked if he felt remorse for his actions, he stated flatly, “I regret nothing except that my daughters betrayed me and federal authority interfered in family matters beyond its jurisdiction.