The “Stupid Farmer Trick” That Destroyed Two Panzers in 11 Seconds

At first glance, it looked like nothing.

Just a patch of ordinary ground in a narrow mountain pass in Tunisia—uneven dirt, a few harmless mounds of soil, the kind of place a tank crew wouldn’t give a second thought. No barbed wire. No mines. No anti-tank guns. No warning signs of danger at all.

And yet, on a cold morning in December 1942, that unremarkable stretch of earth annihilated two German Panzer IV tanks in just eleven seconds—stopping an armored attack cold and rewriting what soldiers thought they knew about warfare.

The man behind it wasn’t an engineer, an officer, or a weapons designer.

He was a quiet farm boy everyone laughed at.

A Joke Dug Into the Dirt

Private First Class Samuel “Sam” Garrett had been mocked for nine straight days.

While the rest of the battalion fortified positions at Fed Pass—laying mines, positioning guns, and rehearsing textbook defenses—Garrett spent his time digging holes with a shovel. He built uneven dirt mounds. He buried scrap wood. He carefully smoothed over a patch of ground until it looked too normal.

To his fellow soldiers, it was ridiculous.

First Sergeant Raymond Kowalski didn’t bother hiding his contempt. During inspection, he planted his boots in the dirt and laughed openly.

“Garrett, I’ve seen dumb ideas,” he said. “But this is the stupidest waste of time I’ve ever witnessed. It wouldn’t stop a Volkswagen—let alone a Panzer.”

The nickname spread fast: “Garrett’s Gopher Mound.”

Even the battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Marcus Peton, was furious.

“We have mines. We have anti-tank guns. We have bazookas designed by people who actually understand how to kill tanks,” he snapped.

“What you’ve built is not a defensive position. It’s an embarrassment.”

Garrett said nothing. He just kept digging.

Because what the others saw as dirt, Garrett saw as behavior.

A Farm Boy’s Education in Traps

Before the war, Sam Garrett grew up on a cattle ranch in South Dakota.

Out there, ammunition was expensive. You didn’t spray bullets and hope for the best. You watched patterns. You learned habits. You studied where animals walked, where they turned, where they felt safe.

His father taught him a simple rule:

“You don’t beat predators with force. You beat them by knowing where they’ll step before they know it themselves.”

Coyotes followed the wind. Prairie dogs used the same paths. Traps didn’t need to look dangerous—they needed to look ordinary.

In Tunisia, Garrett saw tanks the same way he once saw predators.

Not as unstoppable machines—but as heavy, predictable animals.

The Weakness Everyone Ignored

German Panzer IVs were feared for good reason. Thick frontal armor. Powerful guns. Discipline and doctrine.

But Garrett noticed something others didn’t.

Tank drivers avoided uneven ground instinctively. Commanders preferred smooth paths that reduced track damage. And most importantly—a tank’s belly armor was thin.

In a narrow mountain pass like Fed Pass, there was only one “safe” route through: a smooth strip of ground just wide enough for a tank.

Garrett didn’t try to block it.

He let the tanks choose it.

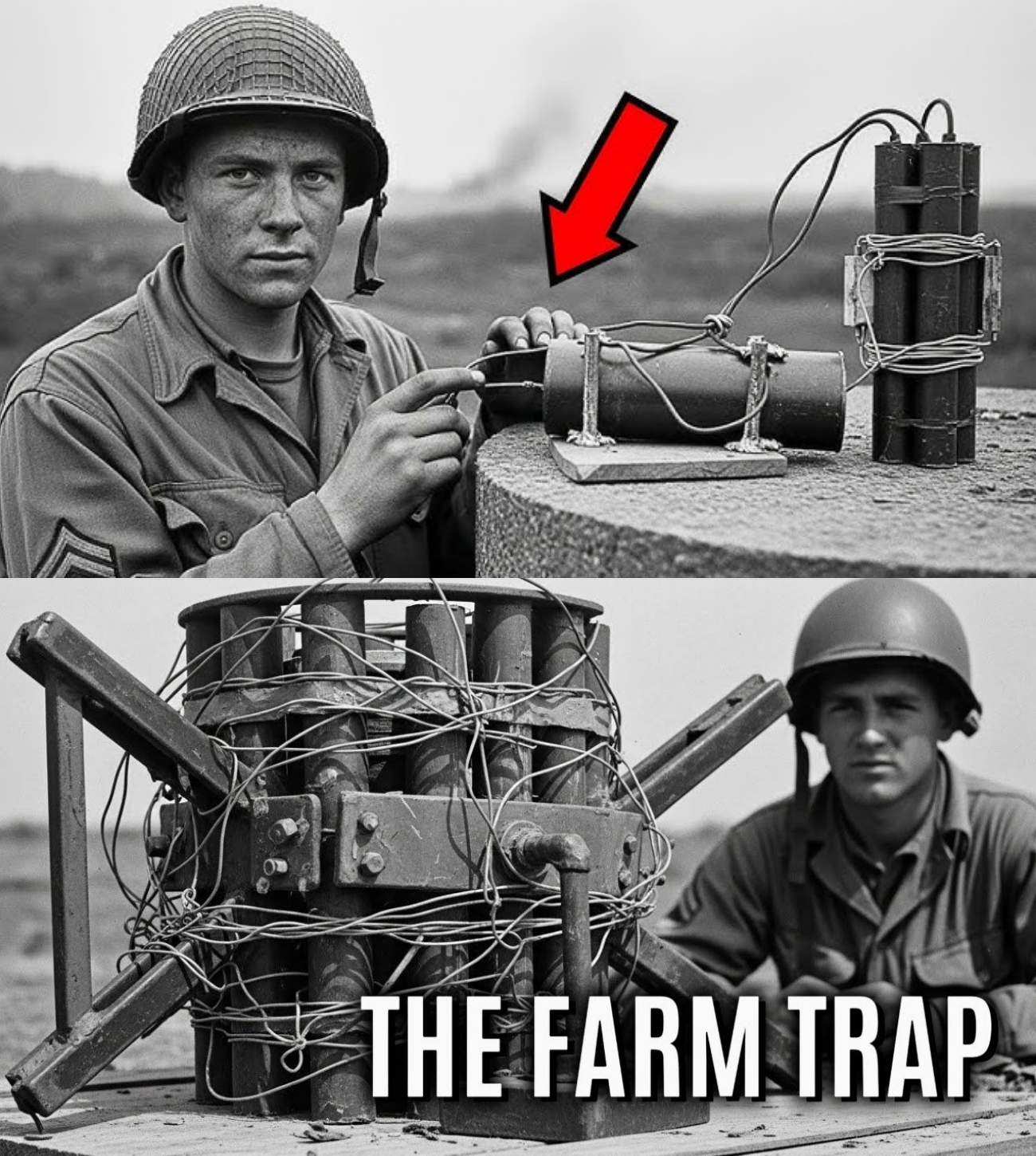

Building a Trap That Didn’t Look Like One

The genius of Garrett’s design wasn’t brute force—it was deception.

The dirt mounds weren’t obstacles. They were steering mechanisms, gently nudging a tank’s path by just a few degrees. Not enough to alarm the driver. Just enough to guide the vehicle exactly where Garrett wanted it.

Seventeen feet beyond the last mound lay the real weapon.

A hidden pit, nine feet deep, covered by a wooden lattice carefully calculated to hold infantry—but not a 45-ton tank. Over it, canvas painted with local soil. On top, real dirt and rocks, matched perfectly in color and texture.

To the eye, it was just ground.

To physics, it was a lie.

Beneath the pit waited four improvised shaped charges, aimed upward at precise angles. Garrett built them from captured German explosives, shaping copper cones by hand. Around the pit, six more charges waited—insurance in case anything survived.

A trap designed not just to stop a tank…

…but to erase it.

“Tear It Down or Face Court-Martial”

When intelligence reported that at least twelve Panzer IVs were forming up for an attack, Garrett’s position became a serious problem.

Colonel Peton summoned him and issued an ultimatum.

“You have 24 hours to fill in your holes and scatter your dirt piles. If you refuse, I will court-martial you for disobeying orders in combat.”

Garrett understood the risk.

But he also knew something Peton didn’t.

If the trap was moved—even a few meters—it wouldn’t work.

That night, instead of dismantling anything, Garrett went back to work. He checked the lattice. Retouched the camouflage. Tested every wire. Every charge.

At dawn, he was summoned again.

“Did you tear it down?” Peton asked.

“No, sir.”

“Why not?”

Garrett met his eyes.

“Because the Germans will drive through that pass, sir. And the trap will stop them.”

Silence.

Then Peton did something unexpected.

“Sit down,” he said. “Explain it to me.”

For the next hour, Garrett taught a colonel how to think like a hunter.

Eleven Seconds That Changed Everything

At 3:15 a.m., German artillery pounded the American positions.

At 3:20, the tanks came.

Five Panzer IVs rolled into Fed Pass, engines growling, commanders scanning the terrain. The lead tank followed the smoothest ground—exactly as Garrett predicted.

The dirt mounds did their quiet work.

The driver adjusted course slightly.

Then committed.

For two seconds, nothing happened.

Then the ground gave way.

The Panzer’s nose plunged into the pit, tilting the hull forward at a brutal 42-degree angle. The belly armor—just 8 millimeters thick—was fully exposed.

At 3:20 and 3 seconds, the charges fired.

Four jets of molten copper punched upward at nearly 7,000 meters per second. One destroyed the transmission. One ripped through the turret basket. One struck the ammunition rack.

The tank exploded from the inside.

Five seconds later, the backup charges detonated.

Eleven seconds after touching that “ordinary” ground, the Panzer IV no longer existed.

The second tank tried to bypass the wreck.

It fell into a second hidden pit.

Another explosion.

Two tanks destroyed in under twenty seconds.

The remaining three reversed in panic and fled.

The German attack was over.

“Your Stupid Farmer Tricks…”

First Sergeant Kowalski stood frozen, staring at the burning wreckage.

He finally walked over to Garrett.

“How many tanks?” he asked quietly.

“Two, Sergeant,” Garrett replied. “Both destroyed.”

Kowalski swallowed hard.

“Your stupid farmer tricks,” he said slowly, “just destroyed two Panzers.”

By morning, the pass was blocked by twisted steel and fire. Officers from across the battalion gathered in disbelief. No shots fired. No guns used. Just dirt, wood, and understanding.

Colonel Peton’s after-action report was blunt:

“Private Garrett demonstrated exceptional understanding of physics, engineering, and enemy behavior. His improvised system destroyed two enemy tanks using materials costing less than $50.”

He recommended immediate promotion.

Fear Travels Faster Than Fire

Captured German reports later described Fed Pass as an “invisible American anti-tank system.”

They believed the ground itself was weaponized.

Armored attacks through mountain passes were suspended.

Garrett went on to build more traps. More tanks were destroyed. Zero American casualties.

Eventually, the U.S. Army wrote a manual inspired by his work—teaching soldiers to read terrain the way hunters read trails.

And after the war?

Garrett went home to South Dakota. He ran the family ranch. He never bragged.

When asked years later why no one else thought of it, he answered simply:

“Most people tried to fight tanks head-on.

I just figured out where they’d step.”

Sometimes, history isn’t changed by bigger weapons.

Sometimes, it’s changed by a farm boy with a shovel—who everyone was too busy laughing at to notice.